Utility of Fluoroscopy in Teaching Trainees Groin Puncture Technique

Abstract: Objectives. To assess trainee physicians’ ability to puncture at the femoral head and complication rates when obtaining access to the common femoral artery using fluoroscopy. Background. The common femoral artery is the most common artery accessed during cardiac catheterization. Fluoroscopy can be used to visualize the femoral head and estimate the common femoral artery location. Puncture superior or inferior to the femoral head is associated with increased rates of retroperitoneal bleeding or thrombosis, respectively. Adequate training in groin puncture technique is essential in minimizing complications and upholding patient safety. Methods. Two consecutive samples of patients were retrospectively analyzed — one from Keck Medical Center (Keck) (n = 45), and one from Los Angeles County-University of Southern California (LAC-USC) (n = 100). An attending interventional cardiologist performed all groin punctures at Keck, and a trainee performed groin puncture at LAC-USC after detailed faculty instruction. A single reviewer retrospectively analyzed all angiograms. Puncture was recorded as occurring above, below, or at the femoral head. Results. Percentage of punctures at the femoral head between LAC-USC vs Keck was not significantly different (93.0% vs 95.6%; P=.26). There was no significant difference in percentage of punctures below and above the femoral head between both groups, and no difference in complications. Conclusion. Femoral artery puncture at the femoral head is associated with improved outcomes. Our data show no significant difference between attending physicians’ and trainees’ ability to puncture at the level of the femoral head. Groin puncture using fluoroscopy can be taught to a high proficiency level with appropriate instruction.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2014;26(1):18-20

Key words: cardiac catheterization, fellow, access, common femoral artery

________________________

The common femoral artery (CFA) is the most commonly accessed artery during cardiac catheterization. Studies have shown that access of the CFA is associated with low postcatheterization complication rates. However, inaccurate puncture location within the CFA increases the risk of complications and compromises patient safety. Risk of retroperitoneal bleeding is increased with puncture superior to the inguinal ligament, and risk of thrombosis and arteriovenous fistula formation is increased if puncture is too low.1 Thus, accurate puncture location is important in minimizing the rate of postcatheterization complications. It is important to successfully teach trainees proper puncture technique as part of their training in an effort to maintain patient safety. Fluoroscopy may be of great assistance in training fellows to perform groin puncture, and minimizing complications and compromised patient outcomes.

Accessing the CFA can be technically challenging. There are various methods that have been implemented in order to best access the artery, some with more success than others. Initially, the most commonly used landmarks during cardiac catheterization were the inguinal skin crease, point of maximal pulsation, or bony landmarks.2 This methodology may provide an inaccurate estimate of the location of the CFA due to obesity or other variations of body habitus.2,3 Common palpable landmarks may be difficult to locate in certain patients, especially those with obesity or low blood pressure.

The femoral head was studied as a potential landmark and found to have a consistent anatomical relationship with the CFA, making it an ideal landmark to locate prior to attempting arterial access.4 Grossman et al first suggested the use of fluoroscopy over the femoral head to locate the CFA in 1974.5 Several studies have confirmed this anatomical relationship.6-8 Baum et al noted that the CFA bifurcation was about 3.4 cm from the inferior margin of the femoral head in a study of 100 patients undergoing computed tomography scanning.7 Studies have suggested that the use of fluoroscopy to locate the femoral head may decrease the risk of postcatheterization vascular complications, indicating that fluoroscopy should be the routine method to determine the femoral artery puncture site.9

While this technique is increasingly used for patients undergoing groin puncture, to our knowledge, no study has assessed how successfully this technique can be taught to trainee physicians. Mastery of this technique by trainee physicians, especially cardiology fellows, is essential since most diagnostic cardiac catheterization-related complications are due to errors in access.1 If trainees can be taught successful puncture of the CFA using fluoroscopy, this can help minimize complications from catheterization and maintain patient safety. After extensively training cardiology fellows in groin puncture technique with the use of fluoroscopy, we aimed to compare rates of successful groin puncture at the femoral head between cardiology fellows and the attending interventional cardiologist.

Methods

Two consecutive samples of patients who underwent cardiac catheterization at the University of Southern California were analyzed — one from Keck Medical Center (Keck; n = 45) and the other from Los Angeles County-University of Southern California hospital (LAC-USC; n = 100) who had undergone cardiac catheterization. Inclusion criteria included all patients undergoing cardiac catheterization at Keck or LAC-USC with the use of fluoroscopy. Only patients who did not have fluoroscopy images available were excluded. Patients at Keck had groin puncture performed exclusively by the trainers, who were attending interventional cardiologists with greater than 15 years of experience. At LAC-USC, groin puncture was performed exclusively by the trainee, who was a cardiology fellow who had undergone extensive one-on-one instruction with an interventional cardiology attending. A total of 5 attending interventional cardiologists and 14 cardiology fellows participated in the study. Angiograms were retrospectively analyzed by a single blinded reviewer and puncture site was recorded as occurring above the femoral head, at the femoral head, or below the femoral head. Patient charts were reviewed and baseline characteristics, including age, body mass index (BMI), anticoagulant use, mortality, and postprocedure complications were recorded and analyzed.

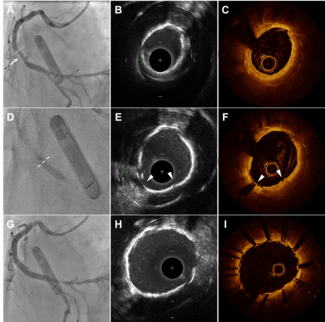

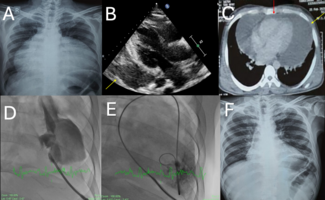

A strict program of fluoroscopic imaging prior to femoral puncture was implemented. The inferior margin of the femoral head was located fluoroscopically and marked with a hemostat on the drape. We postulated that skin entry at the inferior femoral margin of the femoral head, with usual needle angle of entry, would result in CFA puncture in the mid-portion of the vessel.

The attending interventional cardiologist thoroughly explained this technique to the cardiology fellows, through both extensive review of the groin anatomy as well as skills training using fluoroscopy. Attending interventional cardiologists encouraged the fellow to aim at the middle one-third of the femoral head when attempting access of the CFA.

This study was funded by internal funds from the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at the University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine, and was approved by the institutional review board of the university.

Results

A total of 45 patients from Keck and 100 patients from LAC-USC were analyzed. Table 1 describes baseline characteristics. The Keck population was significantly older than the LAC-USC population (61.4 ± 9.9 years vs 57.3 ± 8.6 years; P=.01). There was no significant difference in BMI, aspirin, or clopidogrel use. Smaller sheaths (Fr sheath size <6.5 mm) were more likely to be used at Keck vs LAC-USC (P=.01).

baseline characteristics. The Keck population was significantly older than the LAC-USC population (61.4 ± 9.9 years vs 57.3 ± 8.6 years; P=.01). There was no significant difference in BMI, aspirin, or clopidogrel use. Smaller sheaths (Fr sheath size <6.5 mm) were more likely to be used at Keck vs LAC-USC (P=.01).

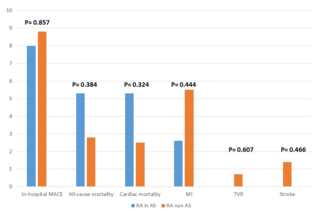

Puncture site was recorded as occurring above, below, or at the femoral head. Punctures at the femoral head were considered successful. There was no significant difference in the overall percentage of successful punctures occurring at the femoral head in attending cardiology fellows vs attending interventional cardiologists(93.0% vs 95.6%; P=.26). There was also no significant difference in percentage of punctures performed below and above the femoral head between both patient groups. The complication rate was low in both patient groups, and not significantly different between cardiology fellows and interventional cardiology attendings (Table 2).

Statistical analysis suggested that, assuming a 95% confidence interval and a power of 80%, 1300 patients would need to be sampled from each hospital to potentially obtain significance between both groups. We therefore concluded that analyzing more patients would be unlikely to impact study outcome. Multivariate analysis adjusting for potential confounders including BMI, age, and medication use confirmed that there was no significant difference in the overall percentage of successful punctures between both groups of patients (P=.92) (Table 2).

patients would need to be sampled from each hospital to potentially obtain significance between both groups. We therefore concluded that analyzing more patients would be unlikely to impact study outcome. Multivariate analysis adjusting for potential confounders including BMI, age, and medication use confirmed that there was no significant difference in the overall percentage of successful punctures between both groups of patients (P=.92) (Table 2).

Discussion

In this single-center retrospective analysis, we found that trainees were able to achieve similar complication rates and successful puncture rates as attending interventional cardiologists while using fluoroscopy. We suggest fluoroscopy as a systematic and reliable tool for training cardiology fellows in groin puncture.

The CFA is accepted as an optimal location for vascular access during catheterization or other percutaneous procedures. Utilization of fluoroscopy has been described as a successful technique in reliably accessing the CFA, and can help avoid certain postcatheterization complications.1,10 Vascular complications during cardiac catheterization can lead to longer hospital stays and increased morbidity and mortality. When trainees learn this technique, it is particularly important that they are trained to proficiency with a safe modality so as to minimize complications and risk associated with vascular access and cardiac catheterization. To our knowledge, no study has evaluated whether trainees are able to successfully learn this procedure, and whether trainees have higher complication rates than their experienced interventional cardiology attending physicians.

The access site has been established as a major contributing factor to vascular complication risk. Accessing the CFA has been thought to reduce the risk of vascular complications.10 Given that incorrect location of groin puncture is a major source of postcatheterization complications, it is imperative that trainees learn to successfully access the CFA. Fluoroscopy is a validated technique to reliably locate the CFA and allows attending physicians to effectively teach this technique to trainees and monitor performance of fellows.1

Fluoroscopy can be used to quickly visualize the femoral head to guide groin puncture with negligible additional radiation. The relation of the femoral head to the femoral artery has been described extensively in the literature. Grossman et al first reported this relationship, which was supported by Garret et al’s findings that the CFA courses over the femoral head in 92% of cases, and the the bifurcation of the CFA is below the middle of the femoral head in 99% of cases.7 Thus, fluoroscopy for detection of the femoral head increases the likelihood of correct sheath placement in the CFA. While traditionally anatomical landmarks have been used, palpation of landmarks can be user dependent and may be affected by the body habitus of the patient or natural variations in anatomy.

Jacobi et al, in a study of 256 patients, compared rates of correct arterial sheath placement in patients undergoing fluoroscopy versus those undergoing blind puncture. This study reported 20% higher rate of correct sheath placement in patients with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 than in the control group.1 Our data show that accurate groin puncture can be successfully taught to trainee physicians with careful one-on-one instruction. We report no significant difference in ability to puncture at the level of the femoral head when comparing trainers to trainees. In comparing two separate populations with similar baseline characteristics, we find that trainee physicians can be just as successful at accurate groin puncture as highly experienced interventional cardiologists when carefully instructed in proper fluoroscopically-guided technique. Furthermore, trainee physicians do not appear to have a significantly higher rate of postprocedure complications. Our findings are important and suggest that fluoroscopy may be useful in teaching cardiology fellows groin puncture technique. There are few disadvantages to use of fluoroscopy for correct sheath placement. While it is an extra step that must be performed and taught, it not only provides greater visualization as the CFA is accessed, it can be done with minimal radiation and with minimal extra time. Fluoroscopy should be considered by educators as a tool to not only teach cardiology fellows, but also to monitor performance. In patients who do have unfortunate complications associated with cardiac catheterization, educators can review fluoroscopy images from sheath placement and use this as a teaching tool to help minimize future complications, should an error occur.

While radial access is gaining increasing popularity due to its undeniable merits, groin puncture continues to be a widely practiced technique during percutaneous procedures. Trainees in specific specialties including cardiology will need appropriate training in access of the CFA as percutaneous procedures continue to become more common. We conclude that fluoroscopy can be a useful modality to train cardiology fellows in successful groin puncture. Implementation of a successful standardized tool such as fluoroscopy to teach cardiology fellows groin puncture is important to maintain patient safety while allowing cardiology fellows to train effectively in procedures including cardiac catheterization.

Study limitations. Our study has several limitations. First, we report a small number of patients from two separate hospitals and compare rates of successful puncture at the femoral head after reviewing fluoroscopy images. We have compared the two populations, however, and do not note any significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two populations that may confound our results. The small number of patients reviewed appeared sufficient to make a meaningful comparison from a statistical standpoint. We also do not have a control group of trainees who were not trained using fluoroscopy. This was not feasible since fluoroscopy to guide vascular access is standard of practice and all fellows at our institution are instructed in groin puncture technique using fluoroscopy. Despite these limitations, we believe our study suggests fluoroscopy as a useful tool for training fellows in groin puncture technique.

Conclusion

In our single-center retrospective study, we find that when using fluoroscopy, cardiology fellows achieve the same rates of successful groin puncture as attending interventional cardiologists, with similar rates of complications with the use of fluoroscopy. Fluoroscopy can prove to be an excellent teaching tool to train cardiology fellows in groin puncture technique while minimizing complications.

References

- Jacobi JA, Schussler JM, Johnson KB. Routine femoral head fluoroscopy to reduce complications in coronary catheterization. Proceedings. 2009;22(1):7-8.

- Grier D, Hartnell G. Percutaneous femoral artery puncture: practice and anatomy. Br J Radiol. 1990;63(752):602-604.

- Lechner G, Jantsch H, Waneck R, Kretschmer G. The relationship between the common femoral artery, the inguinal crease, and the inguinal ligament: a guide to accurate angiographic puncture. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1988;11(3):165-169.

- Dotter CT, Rosch J, Robinson M. Fluoroscopic guidance in femoral artery puncture. Radiology. 1978;127(1):266-267.

- Grossman M. How to miss the profunda femoris. Radiology. 1974;111(2):482.

- Baum PA, Matsumoto AH, Teitelbaum GP, Zuurbier RA, Barth KH. Anatomic relationship between the common femoral artery and vein: CT evaluation and clinical significance. Radiology. 1989;173(3):775-777.

- Garrett PD, Eckart RE, Bauch TD, Thompson CM, Stajduhar KC. Fluoroscopic localization of the femoral head as a landmark for common femoral artery cannulation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;65(2):205-207.

- Schnyder G, Sawhney N, Whisenant B, Tsimikas S, Turi ZG. Common femoral artery anatomy is influenced by demographics and comorbidity: implications for cardiac and peripheral invasive studies. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2001;53(3):289-295.

- Pitta S. Location of femoral artery access and correlation with vascular complications. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;78(2):294-299. (Epub 2011 Mar 16).

- Sherev DA, Shaw RE, Brent BN. Angiographic predictors of femoral access site complications: implication for planned percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;65(2):196-202.