An Unusual Culprit: Simple Angioplasty for a Complex Disease

Abstract: We present the case of an atypical presentation of myelofibrosis presenting with acute inferior-wall ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Besides cigarette smoking, the patient had no known traditional cardiovascular risk factors like diabetes, hypertension, or a sedentary lifestyle. He, however, had a hypercoagulable state due to a myeloproliferative neoplasm. This demonstrates that the typical presentation of a common emergency condition may involve more complex underlying illness, which when identified, may change the approach to the management of the patient for a more optimal outcome.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2013;25(12):687-689

Key words: acute coronary syndromes, acute myocardial infarction, bare-metal stent, thrombus

_________________________

Case Presentation

A 68-year-old male presented to our emergency room with chest pain for the past 4 hours associated with lightheadedness and diaphoresis. Past history was unremarkable except for an episode of chest pain of similar, but less intense, character 1 month ago that lasted for a few minutes and relieved spontaneously. There was no history of fever, dyspnea, palpitations, or lower-extremity edema. The patient was a current smoker with 30 pack years and had no diabetes, hypertension, or family history relevant for coronary artery disease. On physical examination, his blood pressure was 100/60 mm Hg and heart rate was 80 beats/minute. There was no jugular venous distention, and cardiovascular and respiratory examination were unremarkable. Abdominal examination did not reveal any organomegaly or lymphadenopathy.

lower-extremity edema. The patient was a current smoker with 30 pack years and had no diabetes, hypertension, or family history relevant for coronary artery disease. On physical examination, his blood pressure was 100/60 mm Hg and heart rate was 80 beats/minute. There was no jugular venous distention, and cardiovascular and respiratory examination were unremarkable. Abdominal examination did not reveal any organomegaly or lymphadenopathy.

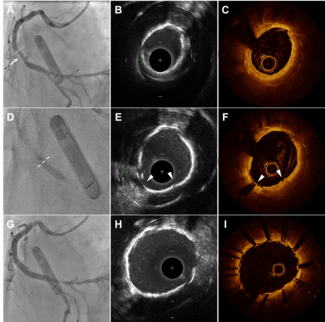

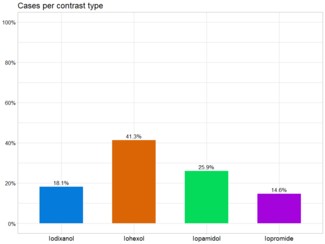

A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF, and cardiac biomarkers were elevated, indicating acute myocardial infarction. Coronary angiography revealed a total occlusion of the proximal right coronary artery with otherwise smooth coronary arteries and no indications for atherosclerotic plaques (Figures 1 and 2). After primary percutanoeus coronary intervention with balloon angioplasty and implantation of a bare-metal stent (Integrity; Medtronic), patency of the right coronary artery was restored with TIMI-3 flow (Figure 3) and the chest discomfort was completely relieved. The patient was started on dual-antiplatelet therapy and admitted in the coronary care unit.

smooth coronary arteries and no indications for atherosclerotic plaques (Figures 1 and 2). After primary percutanoeus coronary intervention with balloon angioplasty and implantation of a bare-metal stent (Integrity; Medtronic), patency of the right coronary artery was restored with TIMI-3 flow (Figure 3) and the chest discomfort was completely relieved. The patient was started on dual-antiplatelet therapy and admitted in the coronary care unit.

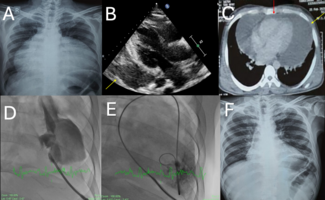

Baseline investigations revealed a hemoglobin count of 9.4 g/dL, white cell count of 24,300/mm3 (neutrophils 84%; lymphocytes 10%; monocytes 6%) and a platelet count of 2,441,000/mm3. The peripheral smear revealed marked thrombocytosis with giant platelets, leucocytosis, with a single blast cell (Figure 4). Ultrasonography of the abdomen revealed mild splenomegaly of 14.6 cm. The serum lactate dehydrogenase was elevated. Testing of peripheral blood for Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) V617F mutation was positive. Bone marrow biopsy revealed absence of the Philadelphia chromosome and the specimen demonstrated a hypercelluar marrow with an increased number of atypical megakaryocytes with a myeloid preponderance with 5% nucleated cells (Figure 5). The erythroid series was normoblastic. The histologic features confirmed a myeloproliferative

2,441,000/mm3. The peripheral smear revealed marked thrombocytosis with giant platelets, leucocytosis, with a single blast cell (Figure 4). Ultrasonography of the abdomen revealed mild splenomegaly of 14.6 cm. The serum lactate dehydrogenase was elevated. Testing of peripheral blood for Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) V617F mutation was positive. Bone marrow biopsy revealed absence of the Philadelphia chromosome and the specimen demonstrated a hypercelluar marrow with an increased number of atypical megakaryocytes with a myeloid preponderance with 5% nucleated cells (Figure 5). The erythroid series was normoblastic. The histologic features confirmed a myeloproliferative neoplasm and a diagnosis of primary myelofibrosis (prefibrotic transforming to fibrotic stage) was made.

neoplasm and a diagnosis of primary myelofibrosis (prefibrotic transforming to fibrotic stage) was made.

Clopidogrel was substituted for ticagrelor since the patient had a marked elevation in the platelet count and we felt safer with a more potent antiplatelet agent. Atorvastatin, enalapril, and metoprolol were continued, and hydroxurea was started at 500 mg three times daily. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed an ejection fraction of 50% with inferior hypokinesia. After an uneventful hospital stay of 12 days, the patient was discharged home. His follow-up investigations performed at 1 month revealed a hemoglobin of 11.1 g/dL, white cell count of 12,000/mm3 (neutrophils 70%; lymphocytes 25%; monocytes 5%) and a platelet count that had decreased to 1,100,000/mm3. He had no chest pain or shortness of breath. He returned for follow-up 3 months post discharge and remained symptom free, and his hemoglobin was 12.2 g/dL, white cell count of 6500/mm3 with a platelet count of 335,000/mm3.

count that had decreased to 1,100,000/mm3. He had no chest pain or shortness of breath. He returned for follow-up 3 months post discharge and remained symptom free, and his hemoglobin was 12.2 g/dL, white cell count of 6500/mm3 with a platelet count of 335,000/mm3.

Discussion

We present the case of an atypical presentation of myelofibrosis with an acute myocardial infarction. Besides cigarette smoking, the patient had no known traditional cardiovascular risk factors like diabetes, hypertension, or a sedentary lifestyle. However, he had a hypercoagulable state due to a myeloproliferative neoplasm.

When a myocardial infarction occurs in a patient who does not have traditional risk factors for coronary artery disease, alternative causes should be sought.1

Myeloproliferative disorders, consisting primarily of polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, primary myelofibrosis, and chronic myelogenous leukemia,2 are associated with hypercoagulability.3,4

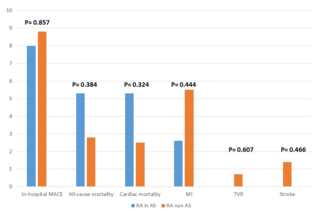

The incidence of thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms is higher than the general population, and arterial thrombosis is more common than venous thrombosis.5,6 Hyperviscosity, platelet-aggregation abnormalities, leucocytosis, and the presence of JAK2 mutations may be accountable for the mechanisms of increased thrombosis in such patients.3,4

The management of thrombocytosis in patients with a myeloproliferative neoplasm consists of antiplatelet and cytoreductive therapies. Aspirin was shown to reduce the incidence of thrombosis, but did not reduce mortality.6 However, patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms paradoxically are also prone to bleeding, which is usually mucocutaneous and usually less frequent and severe than thrombosis, but the potential benefits of using antiplatelet therapies to decrease thrombosis must be weighed against the risks of bleeding. Cytoreductive therapies include phlebotomy, hydroxurea, and interferon alpha. A newer drug, ruxolitinib, which is an inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2, was shown to improve survival as compared to placebo and has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration.7

The presentation that brought the patient to seek medical attention — an acute myocardial infarction — demonstrates that the typical presentation of a common emergency condition may involve a more complex underlying illness which, when identified, may change the approach to the management of the patient for a more optimal outcome.

References

- Leng S, Nallamothu BK, Saint S, Appleman LJ, Bump GM. Simple and complex. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):65-71.

- Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Classification and diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasms: the 2008 World Health Organization criteria and point-of-care diagnostic algorithms. Leukemia. 2008;22(1):14-22.

- Papadakis E, Hoffman R, Brenner B. Thrombohemorrhagic complications of myeloproliferative disorders. Blood Rev. 2010;24(6):227-232.

- Landolfi R, Di Gennaro L, Falanga A. Thrombosis in myeloproliferative disorders: pathogenetic facts and speculation. Leukemia. 2008;22(11):2020-2028.

- Barbui T, Carobbio A, Cervantes F, et al. Thrombosis in primary myelofibrosis: incidence and risk factors. Blood. 2010;115(4):778-782.

- Landolfi R, Marchioli R, Kutti J, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose aspirin in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(2):114-124.

- Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799-807.

From the 1Cardiology Division, Department of Internal Medicine, 2Department of Pathology, and 3Department of Internal Medicine, B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan, Nepal.

Disclosure: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Manuscript submitted August 21, 2013, provisional acceptance given September 9, 2013, final version accepted September 27, 2013.

Address for correspondence: Nikesh Raj Shrestha, MD, FESC, Associate Professor of Internal Medicine, B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan, Nepal. Email: nikeshmd@gmail.com