Tumor Blush in Primary Cardiac Tumors

Primary cardiac tumors are a rare clinical entity. Neoplasms of the heart include both benign and malignant histological types. With an incidence of 0.001%-0.03%, they are much less prevalent than secondary neoplasms.1 Diagnosis is frequently challenging, as patients remain asymptomatic for many years and often present with nonspecific signs and symptoms which may mimic other cardiac disease entities.

Approximately 75% of all cardiac tumors are benign. Atrial myxomas account for 30%-50% of all primary tumors of the heart.1 The benign tumors include lipomas, papillary fibroelastomas, fibromas, rhabdomyomas, and hemangiomas. The malignant tumors consist of various sarcomas: leiomyosarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, osteosarcomas and lymphoma, and primitive neuroectodermal tumors (pheochromocytomas).

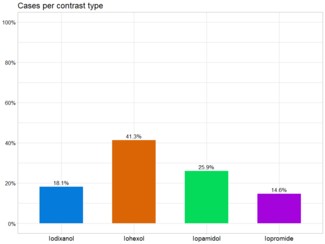

Multiple imaging modalities are available to assess cardiac tumors. The diagnostic evaluation usually includes cardiac catheterization to assess coronary anatomy. In particular, coronary angiography may be performed to determine whether enhancement by contrast or “tumor blush” is present.

Tumors neovascularization is mandatory for tumors to grow in size. The appearance of tumor blush has been described in several, but not all, cardiac neoplasms; notably, benign atrial myxomas, hemangiomas and rhabdomyomas, and malignant pheochromocytomas and angiosarcomas.2-5 Table 1 presents a comparison of the clinicopathological characteristics, including epidemiological features, tumor location, and common clinical features among tumors exhibiting tumor blush.

Tumors neovascularization is mandatory for tumors to grow in size. The appearance of tumor blush has been described in several, but not all, cardiac neoplasms; notably, benign atrial myxomas, hemangiomas and rhabdomyomas, and malignant pheochromocytomas and angiosarcomas.2-5 Table 1 presents a comparison of the clinicopathological characteristics, including epidemiological features, tumor location, and common clinical features among tumors exhibiting tumor blush.

Tumor neovascularization is a requirement for tumors to grow in size. Angiogenesis is required for the enlargement of neoplasms. These abnormal tissues induce blood vessel development by secreting growth factors bFGF and VEGF, which stimulate capillary growth into the tumor. In addition to supplying required nutrients promoting tumor expansion, these vessels serve as a waste pathway, removing metabolic end products produced by rapidly dividing cancer cells. Angiogenesis also facilitates metastasis of malignant tumors through the entry of single or clumps of cancerous cells into the blood vessel, which are then carried to a distant site, where they can implant and grow. The blood vessels in some tumors are mosaic vessels, composed of both endothelial cells and tumor cells, fostering substantial shedding of tumor cells into the vasculature, with subsequent metastasis.

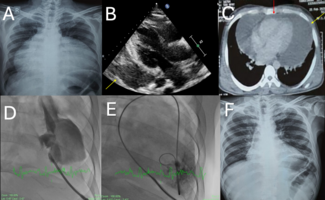

In this issue of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology, Murthy and colleagues6 report a case of a 53-year-old man who was found to have an abnormal electrocardiogram during routine physical exam in whom further cardiac workup revealed a density in the wall of the left ventricle. Cardiac catheterization revealed a tumor blush with dual blood supply from both the diagonal branch of the left anterior descending and a marginal branch of the left circumflex arteries. Surgical removal of the tumor revealed a 1.5 cm hemangioma located in the left ventricle at the base of the posteromedial papillary muscle, as suggested by the location of the tumor blush. It would have been of additional interest to know if the tumor blush was noted to move with mitral valve opening and closing.

Tumor blush is a critical aspect of diagnosis of cardiac tumors. The blush itself is diagnostic of cardiac tumor, and suggests which tumors are likely. The specific epicardial coronary arterial blood supply and the region of the blush aid in tumor localization. Knowing which branches of the main arteries supply the tumor vessels assists in diagnosis since the various tumors tend to appear in specific locations (Table 1). Dual blood supply has been previously described in left atrial myxoma7 and pheochromocytoma,8 but in these cases, the location was atrial; the angiogram in the current case clearly localized the tumor to the endocardium of the left ventricle. The astute diagnostician will usually be able to put together the presence of tumor vessels, its epicardial supply, and its location to develop a short differential diagnosis and suggest a clinical diagnosis without reliance on more advanced imaging techniques.

References

- Burke A, Virmani R. Tumors of the heart and great vessels. In: Atlas of Tumor Pathology. 3rd series, fasc 16. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1996.

- Brizard C, Latremouille C, Jebara VA. Cardiac hemangiomas. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56(2):390-394.

- Shimono T, Komada T, Kusugawa H, et al. Left atrial myxomas: clinical characteristics, evaluation, and considerations in classifying tumors. Nippon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;40(7):1060-1066.

- Gomi T, Ikeda T, Sakurai J, Toya Y, Tani M. Cardiac pheochromocytoma. A case report and review of the literature. Jpn Heart J. 1994;35(1):117-124.

- Krasuski RA, Hesselson AB, Landolfo KP, Ellington KJ, Bashore TM. Cardiac rhabdomyoma in an adult patient presenting with ventricular arrhythmia. Chest. 2000;118(4):1217-1221.

- Murthy A, Jain A, Nappi AG. Tumor blush: left ventricular cardiac hemangioma with supply from both the left anterior descending and circumflex arteries. J Invasive Cardiol. 2012:24(3):138-139.

- Rasmussen KK, Peeples TC, Nellen JR. Unusual variant in tumor vascularity associated with left atrial myxoma. Am J Radiol. 1983;141(5):927-928

- Al-Githmi I, Baslaim G, Batawil N. Primary cardiac paraganglioma with dual coronary blood supply presenting with angina chest pain. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26(7):E278-E279.

___________________________________________

From Advocate Illinois Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois.

Disclosure: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Lloyd W. Klein, MD, Advocate Illinois Medical Center, 3000 North Halsted Suite #625, Chicago, IL 60614. Email: lloydklein@comcast.net