Transradial Retrieval of a Dislodged Stent from the Left Main Coronary Artery

ABSTRACT: We report a case of successful transradial retrieval of a dislodged and mechanically distorted coronary artery stent from the left main stem in an elderly male. Transradial percutaneous coronary intervention was undertaken to reconstruct a lesion in the left circumflex artery complicated by stent dislodgement. A microsnare was used to successfully retrieve the stent.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2008;20:545–547

Coronary stent dislodgement is a rare occurrence in percutaneous intervention and is often associated with significant morbidity.1,2 Retrieval of a dislodged stent can be performed either percutaneously or surgically.2–7 We report a transradial case of stent dislodgement in the left main coronary artery while being delivered to a mid-left circumflex artery (LCx) lesion. The stent was snared successfully, but was unable to be retrieved into the guide catheter, as it was distorted. Consequently, the entire system, including guide catheter, stent, wires and sheath, were removed without complication.

Case Report. An 84-year-old male was admitted with chest pain secondary to a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (non-STEMI). His Troponin I level was 0.36 ug/L, with no ischemic changes on electrocardiography. His past medical history included treated hypertension, cigarette smoking in the past and peripheral vascular disease with an abdominal aortic aneurysm repaired in 1996, which was complicated by a stroke.

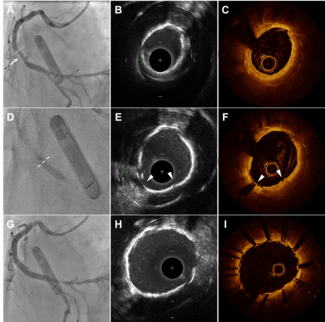

Diagnostic coronary angiography performed via the right femoral artery revealed left main stem disease of 40–50% severity with severe two-vessel disease (Figures 1A and B). The left anterior descending artery (LAD) contained an 80% mid lesion (Type B2) at the bifurcation of the third diagonal artery, and the left circumflex artery (LCx) had a proximal 50% eccentric lesion followed by a mid-to-distal 80–95% diffuse long lesion (Type C). The right coronary artery was anatomically dominant and contained minor irregularities. Left ventricular function revealed mild inferior wall hypokinesis. His Mayo Clinic Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) risk score was 14 (high-risk PCI), and following discussion with the cardiothoracic surgeons, PCI was the preferred revascularization modality. The treatment strategy was first to ascertain the severity of the left main stem (LMS) distal disease by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) analysis and to proceed with rotational stenting of the LMS if it was found to be severely calcified and significant. Second, we felt that the LCx lesion should be treated before the LAD lesion, irrespective of the severity of the LMS lesion.

A right transradial approach was undertaken for the PCI and IVUS due to the patient’s peripheral vascular disease and our experience using this approach for complex coronary interventions. A 6 Fr JL4 guide (Medtronic, Inc, Minneapolis, Minnesota) was used to engage the LMS and a Balance Middleweight 0.014 inch wire (BMW) (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, Illinois) was placed in the distal LAD. IVUS revealed a severe ostial LAD lesion with mild calcification (cross-sectional area [CSA] lumen 3.43 mm2 and maximal lumen diameter [MLD] 1.44 mm) extending into the distal LMS; the LMS lesion was not morphologically significant. We proceeded to perform PCI to the LCx artery lesion using a BMW wire. The mid and distal segments of the artery were sequentially predilated initially using a 2 x 20 mm Ryujin balloon (Terumo Corp., Tokyo Japan) to 12 atm and a 2.5 x 20 mm Powersail balloon (Guidant Corp., Santa Clara, California) to 12 atm. This procedure was complicated by a type A dissection. A 2.5 x 28 mm Taxus stent (Boston Scientific Corp., Natick, Massachusetts) could not be delivered into the mid-LCx artery. We felt that further aggressive predilatation was required and attempted to retrieve the stent into the guide catheter. The procedure was then complicated by stent dislodgement in the LMS.

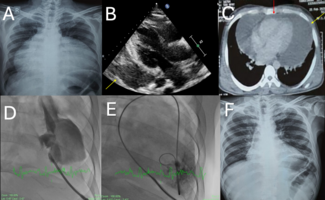

A 5 mm Amplatz Gooseneck™ (ev3, Inc., Plymouth, Minnesota) was passed into the guide and the stent was snared successfully. The snare and stent could not be withdrawn into the guide catheter, and consequently, the snared stent was pulled back to the tip of the guide catheter and the whole system was removed from the radial artery including the radial artery sheath (Figure 2). Close examination of the retrieved stent revealed disruption proximally, which could explain the difficulty encountered while attempting to retrieve it into the guide catheter (Figure 3).

Left femoral artery access was immediately achieved and a repeat IVUS pullback from the LAD confirmed no disruption of the left main stem. Coronary angiogram showed TIMI 3 flow in the LAD and LCx arteries. We abandoned the procedure and the patient was observed over the next 2 days and discharged uneventfully. Eight weeks later, he underwent successful PCI to the calcified mid-LAD. His LCx artery disease has been managed medically. The patient has been medically stable following PCI to his LAD.

Discussion. Transradial PCI is technically challenging. It has fewer associated bleeding complications compared to either a femoral or brachial approach and is often undertaken in patients with peripheral vascular disease in which a femoral approach is not appropriate.8 The incidence of stent dislodgement is uncommon and is lower now than the time when stents were manually crimped, with reports varying between 0.32% and 8%.2,9,10 Dislodgement of a stent can be secondary to severe coronary angulation, calcified coronary arteries, inadequate coronary artery predilatation and direct stenting.2,11 In this case, the IVUS study revealed a severely diseased and mildly calcified ostial LAD that extended marginally into the distal LMS. The mild calcification of the distal LMS as well as the angulated origin of the LCx may have contributed to the difficulty delivering the stent through the LMS into the mid-LCx artery.

Percutaneous stent retrieval can be successfully achieved using a number of techniques including a small-balloon technique, a double-wire technique or a loop snare.2,5,12 These techniques are usually performed via the femoral artery approach. There have been two previous case reports where dislodged stents were successfully retrieved following a transradial approach. The first case involved a dislodged and mechanically disrupted stent which was retrieved only through use of an 8 Fr brachial artery sheath and forceps.13 The second involved an undisrupted stent which was removed via the transradial route using a small-balloon technique.14 This is the first known case report whereby a dislodged and mechanically distorted stent was removed using a microsnare through a 6 Fr sheath via a radial approach with no vascular complications. Although stent retrieval is commonly undertaken through a femoral artery approach, this case highlights the technical feasibility of removing a dislodged stent via the radial artery using a microsnare.

1. Bolte J, Neumann U, Pfafferott C, et al. Incidence, management and outcome of stent loss during intracoronary stenting. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:565–567.

2. Brilakis ES, Best JM, Elesber A, et al. Incidence, retrieval methods, and outcomes of stent loss during percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2005;65:333–340.

3. Fukada J, Morishita K, Satou H, et al. Surgical removal of a stent entrapped in the left main coronary artery. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;4:162–163.

4. Wong PH. Retrieval of undeployed intracoronary Palmaz-Schatz stents. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1995;35:218–223.

5. Bogart DB, Jung SC. Dislodged stent: A simple retrieval technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 1999;47:323–324.

6. Foster-Smith KW, Garratt KN, Higano ST, Holmes DR Jr. Retrieval techniques for managing flexible intracoronary stent misplacement. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1993;30:63–68.

7. Douard H, Besse P, Broustet JP. Successful retrieval of a lost coronary stent from the descending aorta using a loop basket intravascular retriever set. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1998;44:224–226.

8. Kiemeneij F, Laarman GJ, Odekerken D, et al. A randomized comparison of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty by the radial, brachial and femoral approaches: The ACCESS study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;29:1269–1275.

9. Egebrecht H, Haude M, von Birgelen C, et al. Nonsurgical retrieval of embolized coronary stents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2000;51:432–440.

10. Nikolsky E, Gruberg L, Pechersky, et al. Stent deployment failure: Reasons, implications and short- and long-term outcomes. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2003;59:324–328.

11. Laarman G, Muthusamy TS, Swart H, et al. Direct coronary stent implantation:safety, feasibility and predictors of success of the strategy of direct coronary stent implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2001;52:443–448.

12. Hussain F, Rusnak B, Tam J. Retrieval of a dispatched partially expanded stent using the SpdeRX and EnSnare devices — A first report. J Invasive Cardiol 2008;20:E44–E47.

13. Kim MH, Cha KS, Kim JS. Retrieval of dislodged and disfigured transradially delivered coronary stent: Report on a case using forceps and antegrade brachial sheath insertion. Catheter Cardiovtrasc Interv 2001;52:489–491.

14. Patel TM, Shah SC, Gupta AK, Ranjan A. Successful retrieval of transradially delivered unexpanded coronary stent from the left main coronary artery. Indian Heart J 2002;54:715–716.