Is There a Relationship With Coil Use After Coronary Perforation and Ventricular Tachycardia?

To the Editor,

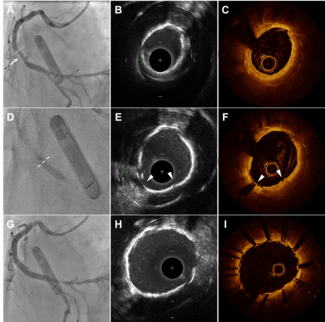

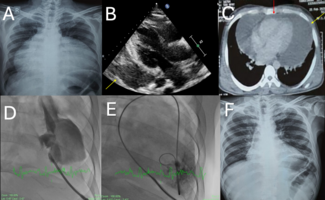

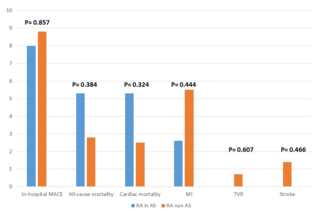

We read with great interest the article “Cardiac Tamponade Complicating Coronary Perforation During Angioplasty: Short-Term Outcomes and Long-Term Survival” by Stathopoulos et al.1 The article addressed an issue on which there is a dearth of literature. It was interesting to note that ventricular tachycardia (VT) arrest was more common in the group with coronary perforation (CP) with tamponade (group A), than with group B (CP without tamponade). The mechanism for this finding is not clear. Ischemic burden could be a possible explanation, but it is hard to know from the data if it is sufficient to cause a significant difference between the two groups. Pericardial effusion as a cause of VT is extremely rare, with only two case reports in the literature.2 We have also noted that more coils were used in group A compared to Group B. Coiling of the septal perforator artery has been used for treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy3 and has also been recently reported for treatment of ventricular arrhythmias.4 These coils are intramyocardial and within an intact vessel structure. However, it is not known if coils extending outside the vessel structure in a perforated vessel and in contact with epicardium/myocardium could potentially cause ventricular irritation and predispose these patients to VT, especially after a complicated procedure. Hence the information from authors on whether VT occurred more in patients in whom coil was used would be interesting.

References

- Stathopoulos I, Kossidas K, Panagopoulos G, Garratt K. Cardiac tamponade complicating coronary perforation during angioplasty: short-term outcomes and long-term survival. J Invasive Cardiol. 2013;25(10):486-449.

- Chowdhry V, Mohanty BB. Pericardial effusion causing ventricular arrhythmias: atypical presentation. Ann Card Anaesth. 2012;15(4):319-320.

- Durand E, Mousseaux E, Coste P, et al. Non-surgical septal myocardial reduction by coil embolization for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: early and 6 months follow-up. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(3):348-355.

- Tholakanahalli VN, Bertog S, Roukoz H, Shivkumar K. Catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia using intracoronary wire mapping and coil embolization: description of a new technique. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(2):292-296 (Epub 2012 Oct 23).

Address for correspondence: Nuri I. Akkus, MD, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Shreveport, 1501 Kings Hwy, Shreveport LA, 71103. Email: iakkus@hotmail.com

Author Reply

We appreciate the interest and the opportunity to provide additional information. Interestingly, none of the patients we treated with occlusive coils developed ventricular tachycardia with arrest. Rather, we observed that ventricular tachycardia was associated with development of tamponade (P=.02 compared with no tamponade). The majority (70%) of patients treated with coils were treated for guidewire-induced coronary perforation. We observed that ventricular tachycardia was uncommon in this setting, despite a trend toward a higher overall rate of tamponade (P=.08 compared with other forms of perforation) that appeared to be driven by the development of delayed tamponade. Certainly, ventricular tachycardia may complicate placement of occlusive coils, and we don’t mean to make any claim to the contrary. Also, we cannot exclude the possibility that the higher rate of long-term mortality after tamponade may have been due, in part, to the use of coils, as mentioned in our article. Still, we’re reassured by the absence of lethal arrhythmias with use of occlusive coils to repair guidewire-induced coronary perforation; this subject is explored further in a separate manuscript currently under review.

Sincerely, Ioannis Stathopoulos, MD, PhD, Konstantinos Kossidas, MD, Georgia Panagopoulos, PhD, Kirk Garratt, MD, MSc