Stress-Induced Cardiomyopathy Shortly After Pacemaker Placement

ABSTRACT: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM), also known as transient apical ballooning syndrome or stress-induced cardiomyopathy, is a distinctive reversible condition often affecting postmenopausal women after a stressful event. The underlying mechanisms have not been elucidated yet, but several hypotheses include catecholamine cardiotoxicity, microvascular dysfunction, and coronary artery spasm. We report the rare case of a 72-year-old woman who developed TCM after undergoing pacemaker placement. Our case emphasizes the importance of recognizing uncomplicated pacemaker implementation as a potential cause of TCM. This should be suspected especially in postmenopausal women who complain of typical chest pain after an uncomplicated pacemaker implantation.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2013;25(11):E207-E209

Key words: stress-induced myopathy, postmenopausal women

______________________

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM), also known as transient apical ballooning syndrome or stress-induced cardiomyopathy, is a distinctive reversible condition often affecting postmenopausal women after a stressful event. The prevalence is between 1.7%-2.2% in patients admitted with suspected acute coronary syndrome,1,2 with increased recent incidence reported among Caucasian Americans. The underlying mechanisms have not yet been elucidated, but hypotheses include catecholamine cardiotoxicity, microvascular dysfunction, and coronary artery spasm.3,4

Case Report. A 72-year-old woman with a past medical history significant for rheumatoid arthritis (on prednisone 5 mg daily and methotrexate weekly) presented to the emergency department (ED) with the sudden onset of substernal chest pain, discomfort, and lightheadedness. The patient had no known cardiac risk factors, but reported feeling extremely dizzy and sporadically short of breath during the past 2 weeks. She denied any particular emotional stressor. On admission, her blood pressure was 106/68 mm Hg, pulse was 46 beats/minute, and body temperature was 97.8 °F. The respiratory and cardiovascular examination results were unremarkable except for bradycardia. Neurological examination revealed no neurological deficits. Laboratory results were within normal limits, including complete blood count, chemistry, cardiac enzymes, and TSH level. Lyme reflex was negative.

was 46 beats/minute, and body temperature was 97.8 °F. The respiratory and cardiovascular examination results were unremarkable except for bradycardia. Neurological examination revealed no neurological deficits. Laboratory results were within normal limits, including complete blood count, chemistry, cardiac enzymes, and TSH level. Lyme reflex was negative.

The electrocardiogram in the ED showed a third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block (Figure 1).

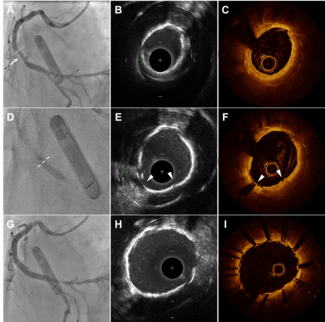

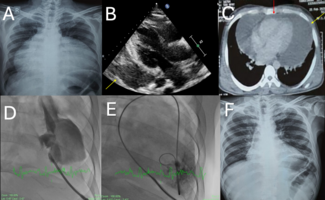

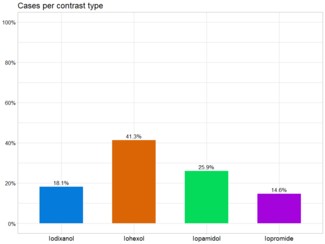

Her symptoms were considered to be the result of a non-reversible cause of complete heart block and she underwent pacemaker placement. A few hours after the procedure, she complained of nausea and lightheadedness. Echocardiogram showed left ventricular (LV) systolic function moderately reduced (ejection fraction, 40%-45%) and a moderate-sized area of apical, anteroseptal, and anterolateral hypokinesis. On the following day, she was asymptomatic and requested to be discharged and undergo complete work-up as an outpatient. Shortly after being discharged, the patient developed sudden onset of midsternal chest pain radiating to her neck and came back to the ED. Electrocardiogram showed electronic ventricular pacing (Figure 2). Laboratory results were remarkable for elevated troponin I (peaked at 0.6 ng/mL). She was taken to cardiac catheterization which revealed normal coronary circulation, but the left ventriculogram showed severely decreased LV systolic function, hypercontractile basal wall but severely hypokinetic to akinetic left ventricle in a pattern consistent with the diagnosis of TCM (Figure 3). The echocardiogram confirmed the same findings (ejection fraction, 30%-35%).

electronic ventricular pacing (Figure 2). Laboratory results were remarkable for elevated troponin I (peaked at 0.6 ng/mL). She was taken to cardiac catheterization which revealed normal coronary circulation, but the left ventriculogram showed severely decreased LV systolic function, hypercontractile basal wall but severely hypokinetic to akinetic left ventricle in a pattern consistent with the diagnosis of TCM (Figure 3). The echocardiogram confirmed the same findings (ejection fraction, 30%-35%).

A systolic heart-failure drug regimen was started, including a beta-blocker and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and the remaining course of her stay was uneventful.

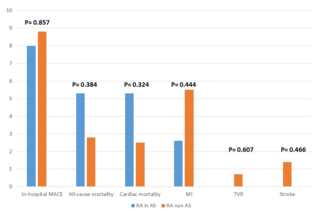

Discussion. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, also known as stress-induced cardiomyopathy, is a distinctive reversible cardiovascular disease that may mimic an acute coronary syndrome. It is more frequent in postmenopausal women after a physical or emotional stressor. Patients with disproportionally high catecholamine responses to stressful events and increased cardiac sympathetic sensitivity, as observed in patients with depression and anxiety, may be prone to have worse clinical outcomes.5 Overall prognosis is good, with low in-hospital mortality rates, and most patients who survived the acute episode usually recover normal LV function few weeks.

sympathetic sensitivity, as observed in patients with depression and anxiety, may be prone to have worse clinical outcomes.5 Overall prognosis is good, with low in-hospital mortality rates, and most patients who survived the acute episode usually recover normal LV function few weeks.

Although uncommon, several authors6-11 have already related TCM to pacemaker implantation. In our patient, this was actually the only identified stressful event. Interestingly, the vast majority of these previous reports6,8-12 had in common the fact that there were minimal or no complications during the implantation itself; however, afterward patients developed a wide variety of symptoms including chest pain, dyspnea, ventricular arrhythmias, and pulmonary edema. Coronary artery disease was insignificant or absent and the left ventricular ejection fraction recovered almost completely within a few weeks of the stressful event.

The cases also all had in common the fact that they were predominantly elderly women with arrhythmias or conduction disorders who underwent pacemaker placement. In many of these patients, it remains unclear whether the complete AV blocks were the initial presentation of TCM or the stressful event that triggered it, although this last option seems more likely. The conduction defect resolved in some patients but persisted in others, even after significant improvement of LV function, which seems to discard any correlation between resolution of conduction defects and LV systolic function recovery. Our patient presented with chest pain a few hours after hospital discharge. This short period of time was spent at home and the patient herself denied any emotional stressor. In the ED, a pneumothorax was ruled out and pacemaker interrogation (which plays an important role in assessing whether the pacemaker mode had any contribution to symptoms) was also obtained. Electrocardiogram showed electronic ventricular pacemaker and coronary angiography showed normal coronary arteries. Since there was no evidence of pheochromocytoma or myocarditis, and there was a modest elevation in cardiac troponin as well as transient hypokinesis of the left ventricular mid segments, the patient met the Mayo Clinic criteria for diagnosis of TCM.13 Another interesting aspect of this case is the cause of complete heart block. We did not find any evidence of acute coronary syndrome, Lyme disease, or hypothyroidism. Our patient was not taking any medications that could potentially be implicated in conduction abnormalities. Rheumatoid arthritis can sometimes lead to conduction abnormalities, including complete AV block; in fact, rheumatoid granulomatous lesions and nodules that infiltrate the conductive system have been described in the literature,14,15 but this seems very unlikely in our case.

Conclusion. Our case report emphasizes the importance of recognizing uncomplicated pacemaker implementation as a potential cause of TCM. This should be suspected especially in postmenopausal women who complain of typical chest pain after an uncomplicated pacemaker implantation.

References

- Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(13):1523-1529.

- Kurowski V, Kaiser A, von Hof K, et al. Apical and midventricular transient left ventricular dysfunction syndrome (tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy): Frequency, mechanisms, and prognosis. Chest. 2007;132(3):809-816.

- Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (tako-tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008;155(3):408-417.

- Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):539-548.

- Nabi H, Hall M, Koskenvuo M, et al. Psychological and somatic symptoms of anxiety and risk of coronary heart disease: the health and social support prospective cohort study. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):378-385.

- Chun SG, Kwok V, Pang DK, Lau TK. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome (takotsubo cardiomyopathy) as a complication of permanent pacemaker implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2007;117(1):e27-e30.

- Kurisu S, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, et al. Persistent left ventricular dysfunction in takotsubo cardiomyopathy after pacemaker implantation. Circ J. 2006;70(5):641-644.

- Kohnen RF, Baur LH. A dutch case of a takotsubo cardiomyopathy after pacemaker implantation. Neth Heart J. 2009;17(12):487-490.

- Golzio PG, Anselmino M, Presutti D, Cerrato E, Bollati M, Gaita F. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy as a complication of pacemaker implantation. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2011;12(10):754-760.

- Siry M, Scheffold N, Wimmert-Roidl D, Konig G. A rare complication of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2011;136(4):129-132.

- Rotondi F, Manganelli F, Di Lorenzo E, et al. Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy in a patient with pacemaker syndrome. Europace. 2009;11(12):1712-1714.

- Inoue M, Kanaya H, Matsubara T, Uno Y, Yasuda T, Miwa K. Complete atrioventricular block associated with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2009;73(3):589-592.

- Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):858-865.

- 14. Ben Hamda K, Betbout F, Maatouk F, et al. Rheumatoid nodule and complete heart block: diagnosis by transesophageal echocardiography. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris). 2004;53(2):101-104.

- 15. OkadaY, Nakanishi I, Kajikawa K, et al. An autopsy case of rheumatoid arthritis with involvement of cardiac conduction system. Jpn Circ J. 1983;47(6):671-676.

From the Danbury Hospital, Danbury, Internal Medicine, Connecticut.

Disclosure: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Manuscript submitted April 16, 2013 and accepted May 13, 2013.

Address for correspondence: Andre Dias, MD, Danbury Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine, 24 Hospital Avenue, Danbury, CT 06810. Email: andremacdias@gmail.com