Same-Day Discharge or Overnight Stay After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Comparison of Net Adverse Cardiovascular Events

Abstract: Background. Same-day discharge after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), if achieved with acceptable safety, could result in greater patient satisfaction and potential cost savings. Comparative analyses reporting the safety outcomes of same-day discharge vs overnight stay after elective PCI are lacking. Methods. Data of same-day discharge and overnight-stay patients undergoing elective PCI in a high-volume center were compared. We specifically evaluated the incidence of net adverse cardiovascular events (NACE; ie, death, myocardial infarction, stroke, target vessel revascularization, vascular complication, and major bleeding) within 48 hours post index procedure among both groups and at 30 days. Results. A total of 188 cases were evaluated, with 93 discharged the same day and 95 after overnight stay following elective PCI. Baseline characteristics were similar, except for older age (73.0 ± 7 years vs 64.0 ± 12 years; P<.001), more prior PCI (49.5% vs 34.7%; P<.001), and prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (16.1% vs 11.6%; P=.01) in the same-day discharge group. Procedural characteristics were similar in both groups. No significant difference in the NACE rate was found between the groups at 48 hours (0 [0%] vs 2 [2.1%]; P=.25) or at 30 days (3 [3.2%] vs 6 [6.3%]; P=.26). Conclusion. In the population studied, same-day discharge after PCI is safe and feasible. Adequately powered randomized prospective studies are necessary to confirm these results.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2014;26(5):204-208

Key words: same-day discharge, day case, overnight stay, percutaneous coronary intervention

_______________________________

Percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) are some of the most commonly performed cardiovascular procedures in current medical practice. Given the cost considerations of these procedures as well as improvements in procedural safety, considerable attention is being given to the rapidity of hospital bed turnover, staffing management, and healthcare expenditure related to PCIs. While a majority of diagnostic catheterizations are performed on an outpatient basis, overnight stay (ONS) is still the standard practice for patients who undergo PCI per current guidelines.1,2 The concern is primarily due to potential abrupt vessel closure, which was as high as 30% in the plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) era, and vascular access-site complications after discharge.3,4 However, the frequent uses of stents, development and miniaturization of![]() interventional cardiology armamentarium, and adjuvant pharmacology have improved the safety and success of PCI procedures.5

interventional cardiology armamentarium, and adjuvant pharmacology have improved the safety and success of PCI procedures.5

Some studies have suggested that outpatient PCI performed via the transradial approach is feasible in selected patients, whereas others have described evidence of the safety of same-day discharge (SDD) after PCI via transfemoral access. However, these studies have evaluated selected low-risk populations, and frequently lack control groups for comparison of outcomes.6-19 Cohort studies with all-comer data reporting safety outcomes of SDD after elective PCI are sparse, and case series evaluating combined ad hoc PCI with femoral access are lacking.

We aimed to evaluate the net adverse cardiovascular event (NACE) rate within 48 hours and at 30 days on all-comer patients who underwent PCI and were managed with a SDD strategy in comparison to an ONS control group.

Methods

Study cohort. After the study protocol was approved by the local institutional review board, retrospective data were collected on 93 consecutive patients discharged on the same day after an uncomplicated elective PCI performed at the Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach, Florida, from January 2011 through January 2012. In order to obtain matched cases in terms of procedural characteristics, retrospective data of 95 consecutive patients who underwent uncomplicated elective PCI and stayed overnight in the hospital for routine observation were collected to serve as the control group. In both groups, the inclusion criteria included: (1) elective PCI for stable angina, stable angina with a positive stress test or crescendo angina, or asymptomatic but positive stress test or perfusion imaging or stenosis on coronary computerized tomography; (2) successful PCI; (3) no angiographic evidence of untreated intimal dissection; (4) absence of unresolved/unexplained postprocedural chest pain; (5) absence of vascular complications at completion of PCI; and (7) PCI performed before 3 pm to allow 6 hours of observation before discharge on the same day. The cases were excluded if any of the following criteria was met: (1) non-ST elevation myocardial infarction or ST-elevation myocardial infarction as indication for PCI; (2) complex PCI (unprotected left main intervention, atherectomy, chronic total occlusions, or interventions on a last remaining vessel); (3) significant procedural complications (prolonged chest pain, transient closure, no-flow or slow-flow phenomenon, hemodynamic instability, persistent electrocardiographic changes, major side-branch occlusion, or an angiographically suboptimal result); (4) unresolved periprocedural hemodynamic or electrical instability; or (5) serum creatinine greater than 2.0 mg/dL. Of note, multivessel PCI was not an exclusion criterion. Ten patients in the SDD group and 8 patients in the ONS group were excluded due to missed follow-up.

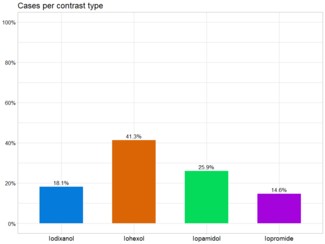

Procedural details. Percutaneous coronary intervention was performed via the femoral approach using 6-7 Fr guiding catheters. All patients were pretreated with aspirin 325 mg and clopidogrel 300 to 600 mg orally before the procedure. The anticoagulation protocol included either intravenous bivalirudin or intravenous heparin with or without glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Procedural success was defined as the establishment of postprocedural TIMI-3 flow, no residual hemodynamically significant dissection or major side-branch loss, and less than 10% residual stenosis after stent deployment.

Vascular access management. Hemostasis following transfemoral accesses was achieved with closure devices, which included Perclose (Abbott Laboratories) and Angio-Seal (St Jude Medical), or by manual compression 2-3 hours after PCI (once activated clotting time was <170 s).

Postintervention care. After PCI, patients were observed in the postprocedure telemetry care unit by skilled staff trained to manage post-PCI complications. All patients were ambulated after 4 hours of bed rest if a closure device was used or after 6 hours if the sheath was removed manually. Written instructions and oral explanation regarding activities, medication compliance, and follow-up were given to all patients.

Follow-up. All patients were scheduled for an office visit with the referring cardiologist or the interventional cardiologist in 2-4 days and then at 4-6 weeks after the index procedure.

Study outcomes. The 48-hour and 30-day NACE rates included the rates of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, repeat target vessel revascularization, major access-site vascular complications, major bleeding, and any stroke within 30 days of index PCI. All events were adjudicated by 2 investigators (AMP and AB) who were not involved in performing the procedures. The death rate was calculated by evaluating hospital medical records and social security number survey. Myocardial infarction was defined in accordance with the universal definition proposed in 2007.20Stroke was defined as focal loss of neurologic function caused by an ischemic or hemorrhagic event, with residual symptoms lasting at least 24 hours or leading to death.21Major bleeding was defined as fatal bleeding, intracranial bleeding, intrapericardial bleeding with cardiac tamponade, hypovolemic shock or severe hypotension due to bleeding and requiring pressors or surgery, and bleeding either associated with a drop in the hemoglobin level of at least 3 g/dL or requiring transfusion of 1 or more units of red cells. Minor bleeding was defined as any bleeding requiring medical intervention but not meeting the criteria for major bleeding. Major vascular complications included the occurrence of one or several of the following: retroperitoneal bleeding, pseudoaneurysm or arteriovenous fistula formation, thrombosis or dissection, or need for vascular surgery. Minor vascular complications were defined as any hematoma up to 10 cm in diameter, and which did not meet criteria for major vascular complication.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 17 (SPSS Institute). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± 1 standard deviation and compared using the unpaired student’s T-test. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and compared using Fisher’s exact test (Chi-square). Significance was assumed when P<.05.

Results

Data of 188 patients who underwent uncomplicated elective PCI from January 2011 through January 2012 were reviewed and analyzed. This corresponds to 15.3% of all PCIs performed at our institution over this period. Of those, 93 were consecutive patients discharged on the same day and 95 were consecutive patients who stayed overnight for observation after elective PCI.

The baseline characteristics are demonstrated in Table 1. The patients in the SDD group were older than in the ONS group (73.0 ± 7 years vs 64.0 ± 12 years; P<.001) and had a more frequent history of prior PCI (46 [49.5%] vs 33 [34.7%]; P<.001) and prior CABG (15 [16.1%] vs 11 [11.6%]; P=.01). There was no statistically significant difference in the distribution of male sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, dyslipidemia, peripheral artery disease, smoking, history of prior myocardial infarction, and concomitant valvular heart disease.

than in the ONS group (73.0 ± 7 years vs 64.0 ± 12 years; P<.001) and had a more frequent history of prior PCI (46 [49.5%] vs 33 [34.7%]; P<.001) and prior CABG (15 [16.1%] vs 11 [11.6%]; P=.01). There was no statistically significant difference in the distribution of male sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, dyslipidemia, peripheral artery disease, smoking, history of prior myocardial infarction, and concomitant valvular heart disease.

Procedural characteristics are shown in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference in the use of drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation, closure devices, multivessel PCI, bifurcation lesion PCI, or proximal left anterior descending PCI. There was no significant difference in the use of bivalirudin or heparin between groups.

lesion PCI, or proximal left anterior descending PCI. There was no significant difference in the use of bivalirudin or heparin between groups.

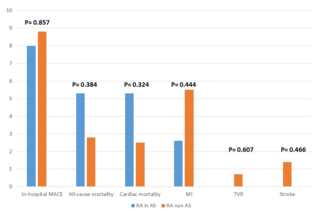

The 48-hour outcomes are illustrated in Table 3. No statistical difference was found between both groups in the rate of composite NACE or in the individual complication rates. There was no death within 48 hours in either group. Overall NACE events occurred in no SDD patients and in 2 ONS patients (2.1%), with no statistically significant difference between groups (P=.25). Both cases counted for NACE were of myocardial infarction (0 patients in the SDD group and 2 patients (2.1%) in the ONS group; P=.25). No major bleeding occurred in either group. There was no minor bleeding in the SDD group and 2 patients (2.1%) in the ONS group (P=.25). There were no major vascular complications (retroperitoneal bleeding, pseudoaneurysm or arteriovenous fistula formation, thrombosis, or dissection) in either group. Minor vascular complications occurred in 2 patients (2.2%) in the SDD group and 5 patients (5.3%) in the ONS group (P=.23). There was no target vessel revascularization or stroke in any patient of either group within the initial 48 hours.

patients (2.2%) in the SDD group and 5 patients (5.3%) in the ONS group (P=.23). There was no target vessel revascularization or stroke in any patient of either group within the initial 48 hours.

The 30-day outcomes are illustrated in Table 4. No statistical difference was found between both groups in the rate of composite NACE or in the individual complication rates. There was no death at 30 days in the SDD group, whereas 1 patient from the ONS group has died from non-cardiovascular causes (P=.51). Overall NACE events occurred in 3 SDD patients (3.2%) and 6 ONS patients (6.3%), with no statistically significant difference between groups (P=.26). No major bleeding occurred in either group. There were no major vascular complications (retroperitoneal bleeding, pseudoaneurysm or arteriovenous fistula formation, thrombosis ,or dissection) in either group. Two patients (2.2%) from SDD group and 1 patient (1.1%) from the ONS group underwent target vessel revascularization (P=.18). One patient (1.1%) from the SDD group and 4 patients (4.2%) from the ONS group had myocardial infarction (P=.19). There was no stroke in any patient of either group.

from SDD group and 1 patient (1.1%) from the ONS group underwent target vessel revascularization (P=.18). One patient (1.1%) from the SDD group and 4 patients (4.2%) from the ONS group had myocardial infarction (P=.19). There was no stroke in any patient of either group.

Discussion

Same-day discharge after PCI, if achieved with acceptable safety, could result in greater patient satisfaction and potential cost savings. Since the late 1990s, outpatient intervention has attracted interest from medical providers and institutions, given the exponential increase in the number of procedures performed, and the consequent need for increased staffing, increased case load on existing staff, hospital bed turnover, and healthcare expenditure that ONS after PCI provokes.22-24 Despite the logistic and economic burden it causes, traditional protocols for ONS following PCI have not been changed due to patient safety reasons, and current guidelines regarding length of stay (LOS) after PCI still recommend ONS, except in selected low-risk patients.1 Despite significant improvement in interventional technology in recent years, there has been only marginal reduction in the post-PCI LOS; the LOS following PCI is one of the major determinants of hospital cost and quality of care assessment.5

Our investigation at a large-volume, multioperator institution analyzing a population of elective PCIs, evaluated whether major outcomes within 48 hours and at 30 days post PCI would be different between SDD and ONS patients — data that are lacking in current literature. The analysis of individual adverse events or composite major adverse cardiac and cardiovascular events showed no difference in a fairly homogeneous sample of patients for both analyzed periods. The baseline characteristics of the population would suggest that the patients in the SDD group were potentially even more prone to have a worse outcome than ONS group, given that they were older, and had more prior PCIs and prior history of CABG. Instead, there was no difference in the event rate. Another feature of the population studied is that higher-risk cases were included. We had a considerable amount of multivessel interventions (15.1%), bifurcation lesions (20.4%), and proximal left anterior descending PCIs (19.4%) in the SDD group, which potentially increases the risk for complications.

different between SDD and ONS patients — data that are lacking in current literature. The analysis of individual adverse events or composite major adverse cardiac and cardiovascular events showed no difference in a fairly homogeneous sample of patients for both analyzed periods. The baseline characteristics of the population would suggest that the patients in the SDD group were potentially even more prone to have a worse outcome than ONS group, given that they were older, and had more prior PCIs and prior history of CABG. Instead, there was no difference in the event rate. Another feature of the population studied is that higher-risk cases were included. We had a considerable amount of multivessel interventions (15.1%), bifurcation lesions (20.4%), and proximal left anterior descending PCIs (19.4%) in the SDD group, which potentially increases the risk for complications.

Several observational studies without control groups have reported single-center experiences with SDD in the United States, Canada, and Oceania, many of them utilizing transradial access only.6,7,11,15-17 Despite the advent of radial interventions, the femoral approach is still the favored technique worldwide.5 These prior studies showed fairly low events, and concluded overall that SDD is a feasible strategy in select low-risk populations. A larger analysis with unpaired data of over 100,000 patients from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry reported the outcomes of SDD in Medicare patients.2 In this cross-sectional analysis with large (although unmatched) data, the authors concluded that SDD could be considered in elderly low-risk patients. Heyde et al8 conducted a large prospective randomized trial in the Netherlands. This study also showed similar outcomes in both groups of SDD and ONS and stated SDD post PCI to be safe and feasible. However, the main exclusion criteria eliminated all ad hoc PCIs, which unlike in Europe, is the most used practice in the United States. More recently, a meta-analysis attempted to combine existing data on post-PCI SDD.25 Despite considerable heterogeneity across published studies comparing SDD after PCI with ONS, with significant variation in the populations studied and the definition of outcomes, the authors concluded that SDD after uncomplicated PCI was a reasonable approach in selected patients.

The confirmatory results we obtained in this study, along with prior observational randomized trials and meta-analyses may help to change the paradigm that hospitalization and admission (ie, ONS) is safer and better than SDD post PCI. A recent systematic database review in a broad spectrum of medical patients has suggested that the risk from a simple ONS in the hospital includes skin ulcer formation (0.4%), adverse drug reactions (3.4%), and infection (11.1%), in a clear indication that simply staying longer in the hospital is not necessarily benign.26 Moreover, the majority of patients seem to prefer the SDD approach when meeting appropriate criteria.27

Although it is likely that individual centers have created their local protocols for SDD after PCI, there is a lack of standardized selection criteria for this strategy and the existing recommendations in the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) statement (endorsed by the American College of Cardiology) on SDD 1 are likely far more conservative than what the current practice may be.6,24 Besides the outcomes we reported regarding SDD in low to moderate risk patients after ad hoc PCI, we also suggest selection criteria that are followed at our institution for patients who could potentially be considered for outpatient PCI (Table 5).

Study limitations. As a retrospective single-center study, undetectable differences in baseline characteristics may have influenced outcomes. Selection bias given the involvement of multiple operators cannot be ruled out as well as operator bias. Our study was not primarily designed to identify predictors of PCI-related complications for SDD.

Conclusion

In a low to moderate risk patient population, SDD after ad hoc PCI is safe and feasible; however, careful and appropriate criteria should be standardized and followed. Randomized prospective studies are still needed to confirm or refute the results.

References

- Chambers CE, Dehmer GJ, Cox DA, et al. Defining the length of stay following percutaneous coronary intervention: an expert consensus document from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;73(7):847-858.

- Rao SV, Kaltenbach LA, Weintraub WS, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of same-day discharge after elective percutaneous coronary intervention among older patients. JAMA. 2011;306(13):1461-1467.

- Singh M, Rihal CS, Gersh BJ, et al. Twenty-five-year trends in in-hospital and long-term outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention: a single-institution experience. Circulation. 2007;115(22):2835-2841.

- Sharma SK, Israel DH, Kamean JL, et al. Clinical, angiographic, and procedural determinants of major and minor coronary dissection during angioplasty. Am Heart J. 1993;126(1):39-47.

- Patel M, Kim M, Karajgikar R, et al. Outcomes of patients discharged the same day following percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3(8):851-858.

- Gilchrist IC, Rhodes DA, Zimmerman HE. A single center experience with same-day transradial-PCI patients: a contrast with published guidelines. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;79(4):583-587.

- Bertrand OF, De Larochellière R, Rodés-Cabau J, et al. A randomized study comparing same-day home discharge and abciximab bolus only to overnight hospitalization and abciximab bolus and infusion after transradial coronary stent implantation. Circulation. 2006;114(24):2636-2643.

- Heyde GS, Koch KT, de Winter RJ, et al. Randomized trial comparing same-day discharge with overnight hospital stay after percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the Elective PCI in Outpatient Study (EPOS). Circulation. 2007;115(17):2299-2306.

- Yee KM, Lazzam C, Richards J, Ross J, Seidelin PH. Same-day discharge after coronary stenting: a feasibility study using a hemostatic femoral puncture closure device. J Interv Cardiol. 2004;17(5):315-320.

- Khater M, Zureikat H, Alqasem A, Alnaber N, Alhaddad IA. Contemporary outpatient percutaneous coronary intervention: feasible and safe. Coron Artery Dis. 2007;18(7):565-569.

- Ziakas AA, Klinke BP, Mildenberger CR, et al. Safety of same-day discharge radial percutaneous coronary intervention: a retrospective study. Am Heart J. 2003;146(4):699-704.

- Van Gaal WJ, Arnold JR, Porto I, et al. Long term outcome of elective day case percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with stable angina. Int J Cardiol. 2008;128(2):272-274.

- Ranchord AM, Prasad S, Seneviratne SK, et al. Same-day discharge is feasible and safe in the majority of elderly patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010;22(7):301-305.

- Dalby M, Davies J, Rakhit R, Mayet J, Foale R, Davies DW. Feasibility and safety of day-case transfemoral coronary stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;60(1):18-24.

- Jabara R, Gadesam R, Pendyala L, et al. Ambulatory discharge after transradial coronary intervention: preliminary US single-center experience (Same-day TransRadial Intervention and Discharge Evaluation, the STRIDE Study). Am Heart J. 2008;156(6):1141-1146.

- Small A, Klinke P, Della Siega A, et al. Day procedure intervention is safe and complication free in higher risk patients undergoing transradial angioplasty and stenting: the discharge study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70(7):907-912.

- Chung WJ, Fang HY, Tsai TH, et al. Transradial approach percutaneous coronary interventions in an outpatient clinic. Int Heart J. 2010;51(6):371-376.

- Muthusamy P, Busman DK, Davis AT, Wohns H. Assessment of clinical outcomes related to early discharge after elective percutaneous coronary intervention: COED PCI. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81(1):6-13.

- Ormiston JA, Shaw BL, Panther MJ, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention with bivalirudin anticoagulation, immediate sheath removal, and early ambulation: a feasibility study with implications for day-stay procedures. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;55(3):289-293.

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116(22):2634-2653.

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(24):e44-e122.

- Koch KT, Piek JJ, Prins MH, et al. Triage of patients for short-term observation after elective coronary angioplasty. Heart. 2000;83(5):557-563.

- Carere RG, Webb JG, Buller CE, et al. Suture closure of femoral arterial puncture sites after coronary angioplasty followed by same-day discharge. Am Heart J. 2000;139(1 Pt 1):52-58.

- Knopf WD, Cohen-Bernstein C, Ryan J, Heselov K, Yarbrough N, Steahr G. Outpatient PTCA with same day discharge is safe and produces high patient satisfaction level. J Invasive Cardiol. 1999;11(5):290-295.

- Abdelaal E, Rao SV, Gilchrist IC, et al. Same-day discharge compared with overnight hospitalization after uncomplicated percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6(2):99-112.

- Hauck K, Zhao X. How dangerous is a day in hospital? A model of adverse events and length of stay for medical inpatients. Med Care. 2011;49(12):1068-1075.

- Ziakas A, Klinke P, Fretz E, et al. Same-day discharge is preferred by the majority of the patients undergoing radial PCI. J Invasive Cardiol. 2004;16(10):562-565.

_________________________________

From the 1Mount Sinai Heart Institute, Miami Beach, Florida, 2Leon Medical Center, Miami, Florida, and 3Columbia University Medical Center and The Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York City, New York.

Disclosure: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Manuscript submitted July 8, 2013 and accepted December 16, 2013.

Address for correspondence: Francisco O. Nascimento, MD, Columbia University, Division of Cardiology, Mount Sinai Heart Institute, 4300 Alton Road, Miami Beach, FL 33140. Email: fonasci@gmail.com