Commentary

Renal Artery Stenting: Continuing to Evaluate the Benefits

July 2004

Renal artery stenosis (RAS) remains a recognized contributor to hypertension and renal insufficiency. Initially, RAS, an infrequently diagnosed, curable cause of hypertension has become a more frequently diagnosed entity. While many of the younger individuals, particularly females have fibromuscular disease, atherosclerotic renal artery vascular disease is more commonly seen in older individuals. Early repair was surgical and associated with a modest complication rate related to the complexity of intra abdominal vascular surgery. With the advent of percutaneous vascular intervention, currently bolstered by more predictable results achieved with stents, renal revascularization has become much more common.

Coincident with the evolution in renal vascular treatment studies have repeatedly demonstrated frequent multiple organ peripheral vascular disease, often including associated coronary artery disease.1 Furthermore, patients with the most severe peripheral vascular disease have the greatest risk of coronary mortality.2 Thus, the concepts of atherosclerosis as a multi-system disease as well as disease severity relating to the probability of cardiovascular events have been well demonstrated.

The frequency of RAS in coronary patients was documented in separate but similar studies by Vetrovec3 and Harding.4 Both studies demonstrated that significant renal artery stenosis was common in patients with coronary artery disease, particularly with co-existent renal insufficiency. Vetrovec3 reported significant renal artery stenosis in 23% of patients undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography with or without hypertension and in 64% of patients with renal insufficiency present with or without associated hypertension. Likewise, Harding4 reported frequent RAS with associated coronary disease and overall an 11% incidence of RAS in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Thus, renal artery stenosis is common among vascular patients particularly in patients with concomitant coronary disease.

The more difficult question is treatment. In older patients with long-standing hypertension, repair of renal artery stenosis is less likely to control blood pressure though stenting often improves blood pressure control. More controversial is renal revascularization for renal preservation. Certain subsets may be improved clinically such as patients presenting with acute pulmonary edema or with acute renal decompensation because of markedly impaired unilateral or bilateral renal blood flow.

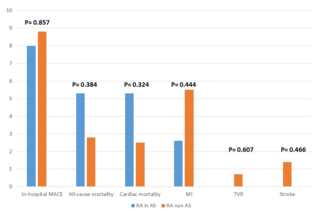

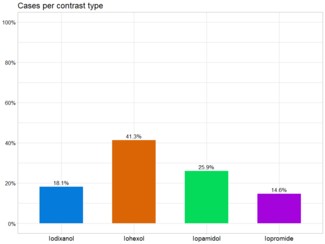

In the accompanying article, Guerrero and colleagues5 report an 83% four year survival for patients with renal artery stenosis undergoing revascularization with stenting. The late outcome was adversely impacted by a higher than might be expected procedure related mortality (2 patients, 1 renal and 1 coronary death, 3%) as well as one late non cardiac death. Not surprisingly, co-existent renal insufficiency and left ventricular dysfunction were significant predictors of higher mortality, as both markedly increase adverse outcomes in all coronary artery disease patients. Unfortunately, there are no data provided on how RAS, renal insufficiency and/or successful stenting may have impacted the concomitant use of ACE inhibitors. The frequency of ACE inhibitor use in a high vascular risk population may have had significant impact on coronary events particularly relating to patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, renal impairment and/or diabetes. The question is relevant because the presence of RAS frequently dissuades practitioners from using ACE inhibitors despite their potential for benefit.6 Also, the relative use of other concomitant risk prevention therapy between survivors and non-survivors could have had a significant impact on outcome. Furthermore, the risk of pre-existent hypertension inducing renal failure is twice as common in African-Americans who comprise the major population of this study. Thus, the late outcomes may be tantalizingly favorable, but with no control group and incomplete data on preventive treatment use as well as unknown population effects, one can only speculate that renal artery stenting was associated with a potentially improved clinical outcome.

Despite these confounding questions, why might renal angioplasty for RAS improve outcome? Perhaps by decreasing renin and consequently aldosterone known to accelerate vascular hypertrophy and adverse remodeling, both associated with an increased risk of coronary events and mortality. Furthermore, ACE inhibitors and more recently aldosterone antagonists have been shown to markedly decrease morbidity and mortality in coronary patients. Perhaps renal artery stenting reduces systemic renin and aldosterone levels, providing a “mechanical” contribution to reducing neurohumoral cardiovascular risk associated with RAS. While interventionalists have focused on the “here and now” of blood pressure control and renal preservation following renal revascularization, more longterm and subtle benefits may accrue. It is tempting to hypothesize that patients with greater vascular disease who are more likely to have RAS, also have higher associated neurohumoral levels which are known to increase the risk of coronary events.

The current study cannot answer these questions but perhaps future registries will make greater efforts to obtain neurohumoral levels before and after intervention as well as clearly documenting concomitant medication use.

Renal artery stenosis is now easy to identify in the coronary population and renal stenting is predictable, generally with low procedural risk. Importantly, a greater emphasis needs to be placed on trying to determine if potential morbidity and mortality benefits accrue to renal artery stenting beyond improving blood pressure control and/or preserving renal function.

1. Aronow WS, Ahn C. Prevalence of coexistence of coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, and atherothrombotic brain infarction in men and women >= 62 years of age. Am J Cardiol 1994;74:64–65.

2. Johansson M, Herlitz H. Jensen G, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality in hypertension patients Relation to sympathetic activation, renal function and treatment regimens. J Hypertens 1999;17:1743–1750.

3. Vetrovec GW, et al. Incidence of renal artery stenosis in hypertensive patients undergoing coronary angiography. J Intervent Cardiol 1989;2:69–76.

4. Harding MB, et al. Renal artery stenosis: Prevalence and associated risk factors in patients undergoing routine cardiac catheterization. J Am Soc Nephrol 1992;2:1608–1616.

5. Guerrero M, A. Syed, S. Khosla. Survival following renal artery stent revascularization: Four-year follow-up. J Invas Cardiol 2004;16:368–371.

6. Frances CD, et al. Are we inhibited? Renal Insufficiency should not preclude the use of ACE Inhibitors for patients with myocardial infarction and depressed left ventricular function. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2645–2650.