Multimodality Imaging of Purulent Pericarditis: Hints to Speed up Diagnosis and Promote Healing

Key words: cardiac imaging, pericardial rinsing, pericardiectomy, pericardiocentesis, purulent pericarditis

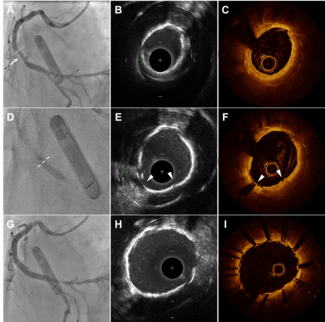

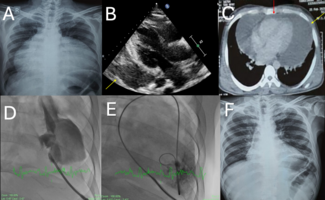

Purulent pericarditis is rare and usually associated with pneumonia, bacteremia, immunosuppression, and thoracic surgery. Often refractory to medical therapy, it has a high risk to develop loculated pericardial effusions and complications like cardiac tamponade (40%-70%) and constrictive pericarditis (3%-30%). Timely diagnosis is essential and imaging may guide the clinical decision making. Echocardiography identifies early signs of hemodynamic compromise, namely, early systole right atrial lateral-wall collapse (Figure A1), early diastole right ventricular collapse (Figure A2) and right atrial filling. Echocardiography in apical view (Figures B1 and B2) adapted to visualize fluctuating fibrin strands. Chest computed tomography scan (Figure C1) showed severe purulent pericardial effusions. Its radiodensity allows an initial discrimination among a transudate (+2 to +20 HU), exudate (+4 to +33 HU), or effusions containing blood cells: purulent (+20 to +40 HU), unclotted blood (+30 to +45 HU), coagulated blood (+58 to +94 HU). Figure C2 shows purulent pericarditis and associated pleural effusion with wavy profiles suggestive of some loculations. Figure D is a chest x-ray showing a “water bottle” enlarged cardiac silhouette typical of pericardial effusions; the combination with pneumonia may suggest a bacterial etiology. Subxiphoid pericardiocentesis in Figures E1 and E2 demonstrates gentle handling of a pigtail catheter within the pericardium or insertion of a long wire segment, creating wide loops to remove any possible loculation, which can increase the effectiveness of drainage. Frankly purulent drainage in Figure F may suggest (along with the fibrin strands in Figures B1 and B2) performing pericardial rinsing to reduce the risk of complications. Blood/fibrin clots and serohematic fluid (Figures G1 and G2) were drained after fibrinolytic rinsing. In case of lack of response to antibiotics, dense adhesions, recurrence of tamponade, or progression to constriction, surgical pericardiectomy should be considered. Figure H demonstrates 5x microscopy of the anatomic specimen.

In the suspicion of purulent pericarditis, a timely diagnostic pericardiocentesis with dedicated maneuvers to improve the effectiveness of drainage and pericardial fibrinolytic rinsing can improve prognosis and prevent a surgical pericardiectomy. Imaging offers useful clues for a more aggressive approach.

From the 1Cardiology Unit, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, Forlì, Italy; 2Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Villa Maria Cecilia, Cotignola (RA), Italy; and the 3Pathology Department, Synlab Italy, Castenedolo (BS), Italy.

Disclosure: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

The authors report that patient consent was provided for publication of the images used herein.

Manuscript accepted April 24, 2019.

Address for correspondence: Gianni Dall’Ara, MD, PhD, Cardiovascular Department ASL Romagna via Forlanini 34, 47121 Forlì, Italy. Email: dallara.gianni@gmail.com