The "May Be Appropriate" PCI: Ambiguities in the Appropriate Use Classification

This editorial discusses

The Appropriate Use Criteria for Revascularization (AUC) are a meaningful response to concerns of overutilization and underutilization. The original AUC1 and a focused update2 set the standard of practice regarding optimal patient selection for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); a new revision is anticipated shortly. The AUC has broad implications for the future of cardiovascular health care, especially in regard to reimbursement. In the future, the AUC will become the foundation for tethering payment decisions and quality assessment to patient-centered therapeutic decision-making.

Since its inception, appraisals of the application of the AUC have concentrated on decreasing the utilization of stenting for inappropriate (new nomenclature: rarely appropriate) interventions. Obviously, this group is a highly reasonable target for quality improvement processes, as procedures classified in this manner will rarely provide medically provable benefit.3 However, a substantially larger and more problematic category is the group designated “uncertain”; although the nomenclature has been changed to “may be appropriate,” this unfortunately does not alter the concerns expressed herein. Uncertain PCI procedures “…may be generally acceptable and may be a reasonable approach for the indication. Uncertainty implies that more research and/or patient information is needed to classify the indication definitively.” This does not mean the procedure should be avoided, but rather that additional clinical factors ought to be considered before making a decision. Since the term suggests that no unconditional verdict can be provided, a considerable amount of judgment is implied. Moreover, no specific guidance is provided regarding how such decisions should be made, although one reasonable inference is that patient preference, age, and co-morbidities are among numerous factors that should be considered.

Unfortunately, this terminology has been misunderstood, and is sometimes construed as indicating when revascularization may be acceptable and reasonable but there is insufficient evidence to conclude whether the benefits outweigh the risks. The implied interpretation of the “may be appropriate” nomenclature is the uncertainty whether the procedure is valuable; however, what this designation was intended to convey in the context of the AUC is the uncertainty if it is more effective compared to medical therapy alone. Essentially, both the new and prior nomenclature accurately reflect the judgment that existing scientific evidence cannot determine confidently which treatment option has the best results in a wide sampling of patients in that scenario. Indeed, the uncertain classification overlaps significantly with class II in the guidelines. One should not therefore infer that PCI is ineffective from the “uncertain” designation, but only that the evidence base does not demonstrate superiority versus non-procedural treatment. Conversely, although it may be acknowledged that medical therapy may be highly effective, that does not denote that PCI has no place in treatment in a particular case.4

The ambiguity is partly due to the lack of clearly defined subcategories of why such proof is lacking. The myriad reasons may include: (1) a lack of study; (2) different conclusions in different trials or populations; (3) when there is genuine uncertainty among experts about the preferred treatment; and (4) when there is true equipoise based on various studies. Unfortunately, the construction of the various scenarios included in the AUC does not include patient preference or other extenuating circumstances commonly encountered in practice that may contribute or ameliorate the uncertainty, and makes no provision for heart team decision making. Although building consensus and adhering to it is the goal, in practice we occasionally encounter clinical scenarios that can only be resolved by expert judgment or with additional details provided in the real-life setting.

An improved understanding of the uncertain classification requires familiarity with the matter in which consensus is achieved in the AUC process. The modified Delphi method solicits the opinions of experts who use their judgment to interpret the evidence; a convergence of opinion toward a relatively narrow interval of values places the result in a specific category. However, another outcome occasionally seen in the RAND process is that opinions may polarize around two distinct values; hence, two divergent points of view emerge. When this happens, the scoring will place the scenario in between (hence, the “uncertain” category) even when both sides are in reality more definite but opposite. This circumstance did occur uncommonly in the AUC process. Further, there may be wide variation in grading merely because of sincere differences of opinion.

The reason cardiologists must have a better comprehension of this category is that reimbursement for revascularization will eventually become dependent on its appropriateness. The current AUC sets four variables as critically important in stable ischemic heart disease (Canadian Cardiovascular Society class, the provision of optimal medical therapy, the severity of angina, and non-invasive risk stratification) and is not modifiable by other factors known to be influential in actual practice, such as age, myocardial viability, frailty, patient preference, and quality of life. This was marginally acceptable when the AUC was initially developed to be the foundation of quality assessment, in which the appropriateness of a particular case was less critical than an operator or a laboratory performing within two standard deviations of the mean level of appropriateness. That would no longer be pertinent if third-party payers are determined to disallow payment in individual cases based solely on AUC categorization. The mechanism could encompass a number of approaches: differential payment for demonstration of a low percentage of rarely appropriate case selection, perhaps some form of benchmarking, or it could be a case-by-case denial or approval of payment.

There are several clinical scenarios in stable ischemic heart disease that the AUC matrices categorize as “may be appropriate” but which frequently in clinical practice are considered highly appropriate for revascularization. Such scenarios include cases with intermediate-sized defects on stress testing, when there is a discrepancy between symptom and stress test abnormality severity, and when there is moderate-severity angina in the absence of maximal medical therapy. In clinical practice, cardiologists frequently consider these situations highly appropriate for revascularization when significant coronary disease is found. When 85 United States cardiologists were queried as to their agreement with AUC classifications, among indications classified as uncertain, there was only 73% concordance (16/22) between the clinical cardiologist group and the AUC, the lowest of any of the categories.4 Overall, there was substantial variation in appropriateness ratings between individual physicians and the AUC Technical Panel (weighted kappa range, 0.05-0.76). When clinical cardiologists are given vignettes covered by the AUC, despite general agreement, there were marked differences within the uncertain category.5

The role of stress testing is central to delineating appropriateness. The best evidence-based practice requires evaluating risk by non-invasive risk stratification (as low-, intermediate-, or high-risk). The provision of quality care requires an interpretation of the severity of inducible regional wall-motion abnormalities or perfusion defects as small, moderate, or large, yet there is no universal, quantifiable standard for this adjudication.6 For this reason, many cardiologists believe that it is a fallacy to make the stress test result so central to determining appropriateness. For example, a small apical defect can be associated with a critical proximal left anterior descending stenosis. Defining the appropriateness of such an intervention based on the outcome of imaging tests, and not on the angiographically apparent territory at risk, has resulted in an awkward attempt to objectify clinical decisions. In reality, interpreting the degree of ischemia from these imaging tests is highly subjective, and making appropriateness dependent on this interpretation is not necessarily in our patient’s interest.

Good clinicians fine-tune their assessments and make adjustments in their strategic approach as more medical data become available, but according to existing standards, once a procedure is considered “may be appropriate” based on just a few variables, no additional information can change it. Interestingly, both the severity of symptoms and the number of anti-ischemic agents the patient is taking are reported by the physician and are simple to manipulate. Therefore, to base reimbursement decisions entirely on these parameters could lead ultimately to progressive reporting inflation.

Recent studies clearly demonstrate trends in the uncertain category, which highlight why this is the critical designation interventionists must be concerned with in the future:

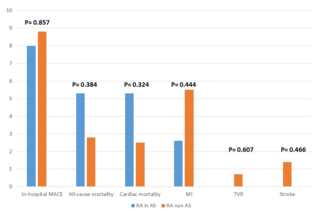

- In the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR), Chan et al7 analyzed 500,154 PCIs from 2009 to 2010 using the 2009 AUC, of which 144,737 procedures were considered non-acute PCIs. The uncertain category in this group was found to include 38% of that group.

- In New York, Hannan demonstrated that 90.0% of coronary artery bypass graft procedures were considered appropriate, while just 8.6% were ranked as uncertain. In contrast, only 36.1% of PCIs were rated appropriate and 49.6% were of uncertain appropriateness.8

- More recently, Washington State9 published AUC findings in procedures performed between 2010 and 2013. The proportion of elective PCIs classified as appropriate increased from 26% in 2010 to 38% in 2013, whereas the proportion of inappropriate PCIs decreased from 16% to 13% (P<.001 for trends). The overall number of PCI decreased by 6.8% (13,267 PCIs in 2010 to 12,193 in 2013), with a 43% decline in the number of PCIs for elective indications (3818 PCIs in 2010 to 2193 PCIs in 2013), which the editorialists interpreted as being due to a decrease in inappropriate procedures. However, it was the number of procedures in the uncertain category that actually shrank the most.

- These findings are similar to those of Desai and colleagues10 using the NCDR database reporting the 5-year findings of Chan et al.7 The authors found that during the 5 years from 2010-2014, the percent of inappropriate PCIs decreased from 26% to 13%, but interestingly, the uncertain category decreased about the same amount, from 44% to 13%. Their conclusion, that applying the AUC in contemporary practice “limits non-acute PCI procedures to those patients most likely to benefit from revascularization,” clearly indicates the interpretation that PCIs in this category are not likely to be beneficial – which is not inconsistent with its nomenclature.

- Bradley and colleagues11 performed a post hoc analysis of 2287 COURAGE trial patients with stable ischemic heart disease randomized to PCI with optimal medical therapy (OMT) or OMT alone. They found that there were no significant differences between PCI and OMT alone in the rate of mortality and myocardial infarction by appropriateness classification. Rates of repeat revascularization were significantly lower in patients initially receiving PCI + OMT who were classified as appropriate (hazard ratio [HR], 0.65; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53-0.80; P<.001) or uncertain (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.32-0.76; P=.001). Patients classified as appropriate by the AUC had better quality of life at 1 month in the PCI-treated group versus the medical therapy group, but health status scores were similar throughout the first year of follow-up in PCI + OMT patients versus OMT alone in patients classified as uncertain. The trends observed are important: when AUC was assessable, the percent of uncertain PCIs ranged between 34%-41% each year in the non-acute indication group. Hence if any downward trend attributable to the AUC exists, it is a small one.

- Thomas and colleagues12 showed that in the NCDR, geographic variations in appropriateness and PCI volumes are quite evident. Moreover, appropriateness varied with quintile of volume, with centers performing the fewest PCIs showing a lower percent of appropriate and uncertain cases, and more unclassifiable cases.

These findings are of interest because they demonstrate that a large proportion of PCI cases are being performed in patients for indications that are not class I and for which the evidence base is ambiguous. Under most circumstances, this would be recognized for what it is: a place in science where no answer is definitive. When quality improvement and assessment are the object of the AUC, such gray areas are predictable and acknowledged. Unfortunately, when money is the object, it is a prime situation where an agenda to cut costs at any cost may wreak havoc with patient care. Although a 2016 AUC revision is soon to be published, only the specific criteria to be included in the “may be appropriate” category will change, and will not impact the questions raised in this commentary.

Reimbursement for revascularization may eventually be dependent on its appropriateness, depending on the future of the fee-for-service model, which will be assessed using the AUC or a close modification. Several states, including New York and Washington, have strongly considered such ties13 for PCI, and this has been the subject of concern in other specialties.14 Since the AUC and its structure were never intended as a means to determine payment for procedures on a case-by-case basis, there is substantial trepidation within the interventional community over its application for this purpose. Whether or not criteria originally intended for quality assessment and professional improvement can be transferred and accurately used for denial of payment is unexplored. If the appropriateness decision is made by a person whose incentive is to find ways to save expenses for a third-party payer, this vagueness could be gamed by insurers and used as an excuse to deny payment. These providers could conceivably decide that only “appropriate” procedures are reimbursable, removing the physician-patient interaction in centered care, and possibly undervaluing the significance of symptoms and pharmacologic adverse events. When reimbursement criteria are generated that find controversies, differences of expert opinion, or lack of hard scientific “proof” to be fertile ground for payment denial, it risks the ultimate goal of patient-centered care.15 The “uncertain” category is precisely where such cases reside, and interventional cardiologists should be wary of simplified or shorthand nomenclature, which lumps this group together with “inappropriate,” making it a target for “improvement.”

References

1. Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, et al. ACCF/SCAI/STS/AATS/AHA/ASNC Appropriateness Criteria for Coronary Revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:530-553.

2. Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, et al. ACCF/SCAI/STS/AATS/AHA/ASNC 2012 Appropriateness Criteria for Coronary Revascularization Focused Update. Relationship between procedure indications and outcomes of percutaneous coronary interventions by ACC/AHA Task Force Guidelines. Circulation. 2005;112:278602791.

3. Marso SP, Teirstein PS, Kereiakes DJ, Moses, J, Lasala J, Grantham JA. Percutaneaous coronary intervention use in the United States. Defining measures of appropriateness. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:229-235.

4. Chan PS, Brindis RG, Cohen DJ, et al. Concordance of physician ratings with the appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1546-1553.

5. Lin FY, Rosenbaum LR, Gebow D, et al. Cardiologist concordance with the American College of Cardiology appropriate use criteria for cardiac testing in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:337-344.

6. Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, et al; for the COURAGE Investigators. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial: nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008;117:1283-1291.

7. Chan PS, Patel MR, Klein LW, et al. Appropriateness of percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2011;306:53-61.

8. Hannan EL, Cozzens K, Samadashvili Z, et al. Appropriateness of coronary revascularization for patients without acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1870-1876.

9. Bradley SM, Bohn CM, Malenka DJ, et al. Temporal trends in percutaneous coronary intervention appropriateness: insights from the clinical outcomes assessment program. Circulation. 2015;132:20-26.

10. Desai NR, Bradley SM, Parzynski CS, et al. Appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization and trends in utilization, patient selection, and appropriateness of percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2015;314:2045-2053.

11. Bradley SM, Chan PS, Hartigan PM, et al. Validation of the appropriate use criteria for percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with stable coronary artery disease (from the COURAGE trial). Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:167-173.

12. Thomas MP, Parzynski CS, Curtis JP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention utilization and appropriateness across the United States. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0138251.

13. Feldman DN, Naidu SS, Duffy PL. Inappropriate use of the appropriate use criteria as a guide for coverage. J Invasive Cardiol. 2014;10:559-561.

14. Fogel RI, Epstein AE, Estes NAM III, et al. The disconnect between the guidelines, the appropriate use criteria, and coverage decisions: the ultimate dilemma. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:12-14.

15. Klein LW. How do interventional cardiologists make decisions? Implications for practice and reimbursement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:989-991.

From Advocate Illinois Medical Center and Rush Medical College, Chicago, Illinois and Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California.

Disclosure: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein. Dr Klein was a technical panel member of the 2009 Revascularization AUC, the 2012 update, and is a peer reviewer for the 2016 revision.

Address for correspondence: Lloyd W. Klein, MD, FSCAI, Advocate Illinois Medical Center and Rush Medical College, Chicago, IL 60614. Email: lloydklein@comcast.net