Feature

Introduction: P3 Summit: Platelet Inhibition Post-PCI

March 2003

The P3 Summit meeting was held in Washington, D.C. on September 23, 2002 and was designed to provide an opportunity to discuss the substantial volume of new data that have emerged on the subject of platelet inhibition post-PCI. The presentations and subsequent round table discussions at the P3 Summit are the subject of this special supplement to the Journal of Invasive Cardiology.

Over the past several years, a great deal of discussion has focused on glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition acute antiplatelet therapy and, to a lesser degree, on longer-term antiplatelet therapy and how practitioners can most effectively segue from acute treatment into longer-term treatment. The goal of the P3 Summit was to discuss the scientific rationale for the treatment strategies currently available to acute coronary syndrome patients who go on to have percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and how these therapies can be incorporated into current practice.

This supplement begins with Deepak Bhatt’s article entitled Diffuse Coronary Disease and Atherothrombosis — A Rationale for Long-term Therapy to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events. Dr. Bhatt highlights the fact that there is a disconnect between acute treatment of the culprit lesion and longer-term treatment of the patient’s overall coronary disease. It is now evident that medical therapy and endovascular therapy should no longer be viewed as mutually exclusive, rather, they should be harmonized. Research has shown that both long-term antiplatelet therapy and anti-inflammatory therapy have a future in the treatment of diffuse coronary disease and atherothrombosis, and it is possible that these therapies are interconnected and that the same agents will be effective in both pathways.

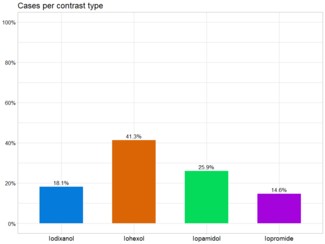

Next, Steven Steinhubl discusses aspirin and the new data emerging on aspirin resistance and dosing. Dr. Steinhubl has participated in several trials involving the rapidly advancing field of antiplatelet therapy. These trials have revealed that an individual propensity for thrombosis exists which is partly related to a variability in coagulation factors and platelet activity. Dr. Steinhubl also points out that despite the lack of conclusive evidence, it has become increasingly clear that aspirin resistance is a reality. In regard to aspirin dose and efficacy, a meta-analysis of several randomized trials revealed a consistent benefit with aspirin use, with no significant difference in terms of low-, medium-, or high doses. Thus, despite the fact that there was no clear efficacy dose-response over 30 mg, a clear dose response was evident in terms of side effects.

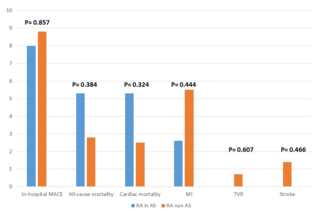

Shamir Mehta’s article, entitled Aspirin and Clopidogrel in Patients with ACS Undergoing PCI, presents the latest data from the CURE and PCI-CURE trials. The CURE data show that when stratified by TIMI risk score, significant benefit is offered with clopidogrel in low-, moderate-, and high-risk patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes and that the benefit/risk ratio favors clopidogrel use early- and long-term. The PCI-CURE substudy was the first to show that patients with acute coronary syndromes who undergo PCI benefit substantially from long-term clopidogrel therapy. Furthermore, the data from CURE and PCI-CURE clearly show that even in non-ST elevation ACS patients undergoing PCI, the benefits of clopidogrel are far greater than the associated bleeding risks.

The article Chris Cannon prepared, entitled Improving Acute Coronary Syndrome Care: The ACC/AHA Guidelines and Critical Pathways, highlights the recently updated ACC/AHA guidelines for acute coronary syndromes and their implementation, as well as the importance of critical pathways. The latest ACC/AHA guidelines recommend targeting the number of antithrombotic agents given to the risk of the patient. The guidelines have now downgraded the addition of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor on top of aspirin, heparin, and clopidogrel from Class I to Class IIa status due to the lack of data from randomized trials on the combination of these agents. When upstream use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors is compared with platelet activation inhibitors such as aspirin and clopidogrel, it becomes apparent that the former is an excellent acute therapy for high-risk patients, while the latter is beneficial in both short- and long-term therapy for all patients. Furthermore, data from five randomized trials have shown that the invasive strategy is clearly beneficial and that it is not necessary to catheterize every patient. According to the updated ACC/AHA guidelines, five baseline therapies — aspirin, clopidogrel, heparin or LMWH (enoxaparin is the preferred antithrombin), beta-blockers, and nitrates — are recommended for all patients. When patients are risk stratified, invasive treatment and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors confer the greatest benefit to those in the higher-risk group. In terms of long-term management post-ACS, the ACC/AHA guidelines now strongly encourage the initiation of secondary prevention medications and the modification of risk factors. The implementation of critical pathways programs, such as CHAMP, GAP, and Get with the Guidelines, have proved very effective in closing the gap between what practitioners know and what they actually do in everyday practice. Also, national and international registries, though underutilized, provide a means by which practitioners can monitor their performance and understand more clearly what exactly they are doing.

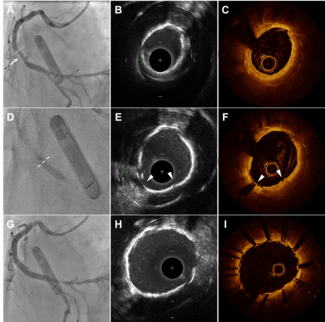

In an article entitled Long-term Antiplatelet Treatment Post-PCI: Brachytherapy and Drug-eluting Stents, Jeffrey Moses discusses how brachytherapy was the first effective treatment for patients with diffuse in-stent restenosis. Unfortunately, it was found that inhibiting neointimal hyperplasia could lead to late thrombosis. Upon closer analysis, however, the multivariate predictors of symptomatic late thrombosis were found to be characterized primarily by long lesions and new stent use. It has since been determined that, in terms of brachytherapy, a six-month regimen of clopidogrel is safe when a new stent is not being implanted. The most recent data show that if a new stent is implanted, then indefinite clopidogrel use is the only safe therapy. Recent data from the RAVEL trial and a smaller study from Sao Paolo show that drug-eluting stents are very effective in their ability to inhibit restenosis. Dual antiplatelet therapy will be key to the safety of drug-eluting stents, and longer duration of antiplatelet therapy will likely be necessary as practitioners begin to treat more complex lesion subsets than what the current clinical trials have focused on.

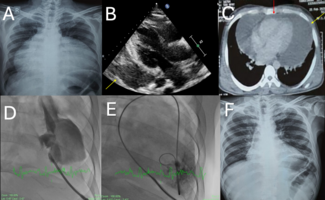

This supplement concludes with four case presentations by Jeffrey Popma and Deepak Bhatt. Each case is followed by a discussion among the participants who attended this round table meeting.