An Impressive Case of Honeycomb In-Stent Restenosis

Giovanni Lorenzoni, MD; Pierluigi Merella, MD; Graziana Viola, MD; Nicola Marziliano, PhD; Gavino Casu, MD

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2018;30(9):E99.

Key words: in-stent restenosis, neoatherosclerosis, optical coherence tomography

A 48-year-old man with previous history of ischemic heart disease was admitted for unstable angina. Two years prior, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with zotarolimus drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation were performed in the mid right coronary artery (RCA) for an acute coronary syndrome without persistent ST elevation.

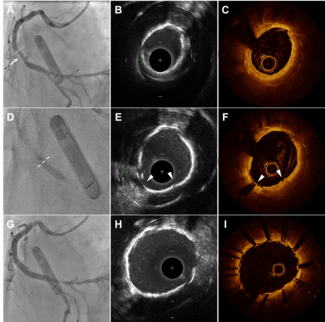

Cardiac imaging (Figure 1) showed very tight in-stent restenosis, as well as good expansion and optimal apposition of the stent implanted 2 years prior; considerable neoatherosclerosis and multiple tubular structures organized in a “honeycomb” pattern were also evident. We performed in-stent dilations with non-compliant and drug-coated balloons at the restenosis site, and then proceeded to optical coherence tomography (OCT)-guided PCI and everolimus DES implantation in the proximal RCA. A good angiographic result with OCT confirmation was obtained.

Despite considerable efforts in reducing the incidence of restenosis with first- and second-generation DESs, in-stent restenosis (ISR) requires target-vessel revascularization in about 5%-10% of cases. One mechanism of late ISR is neoatherosclerosis, which is defined as “the presence of atherosclerotic disease within the neointima of the stented segment.” Neoatherosclerosis is more frequent in DES vs bare-metal stents; the ISR pattern on OCT is different between the early and the intermediate-late post-implantation stage.

Our case shows an impressive “honeycomb” pattern of neoatherosclerosis in the context of very late ISR. OCT is the most useful intravascular modality for evaluating pathology of the coronary artery after stent implantation. In this case, OCT excluded the most common mechanisms of late ISR, underlying the complexity of this unpredictable disease.

From the Ospedale San Francesco, Unità Operativa Complessa di Cardiologia, Nuoro, Italy.

Disclosure: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Manuscript accepted April 9, 2018.

Address for correspondence: Giovanni Lorenzoni, MD, Ospedale San Francesco, Unità Operativa Complessa di Cardiologia, via Mannironi 1, Nuoro, Italy. Email: giovannilorenzoni@alice.it