Vascular Disease

Impact of Gender on In-Hospital Outcomes following Contemporary Percutaneous Intervention for Peripheral Arterial Disease

August 2005

Women with coronary artery disease (CAD) are known to have a higher prevalence of co-morbidities than men, including advanced age, hypertension, diabetes and concomitant non-cardiac disease. Female gender has been shown to be an independent risk factor for morbidity and mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI),1,2 although this gender difference is diminishing with improvement in new techniques, technology advancements and pharmacologic treatments.3–5

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a subclinical marker of CAD and is equally prevalent in men and women over age 40.6 Women undergoing surgery for PAD have a higher risk of perioperative myocardial infarction (MI), vascular complications and bleeding.7–9 Percutaneous peripheral arterial intervention (PPAI) has emerged as an effective and less invasive alternative to surgical therapy, however, data on gender differences on outcomes of PPAI for PAD, especially in the stent era, are limited.

The purpose of this study was to assess the gender differences in the characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of patients undergoing PPAI for PAD in a single center.

Methods

Patient population. We analyzed data on 268 consecutive patients who underwent PPAI for PAD (excluding carotid angioplasty, endovascular aortic aneurysm repair, or concomitant coronary intervention) in the cardiac catheterization laboratory between October 2001 and January 2004 at a single center. All procedures were performed by 3 interventional cardiologists experienced in peripheral endovascular interventions.

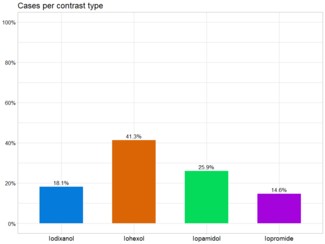

Procedure. Arterial access was obtained via the femoral or brachial approach for all procedures. Percutaneous procedures were performed using rheolytic thrombectomy, balloons or stents, with distal protection device use at the discretion of the operators. Anticoagulation was achieved using either weight-adjusted heparin or bivalirudin to achieve the activated clotting time (ACT) between 250–300 seconds. Femoral arterial sheaths were removed either manually when the ACT was Definitions. Lesion success was defined as attainment of 3 g/dl, any decrease in hemoglobin > 4 g/dl, or transfusion of 2 or more units of packed red blood cells. Minor bleeding was defined as clinically overt bleeding that did not meet the criteria for major bleeding. These adverse events were adjudicated by an independent observer.

Statistical analysis. Quantitative data are presented as mean value ± 1 SD, and qualitative data as frequencies. Continuous variables were compared using unpaired Student’s t -tests or the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were examined by the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. All probability values are two-tailed, and a p-value Results

Baseline clinical and lesion characteristics (Tables 1 and 2). Of the 268 patients, 122 (45.5%) were women. A total of 346 vessels (women: 159, men: 187) and 405 lesions (women: 184, men: 221) were treated. Prior history of coronary intervention was more prevalent in men than women. Current smokers were more frequently found in women. Body mass index was similar between women and men, but women had smaller body surface area. For patients who had lower extremity arterial interventions, the left side ankle:brachial index was lower in women than men (0.58 ± 0.22 versus 0.70 ± 0.19; p = 0.003). Lesion characteristics were similar, except upper extremities interventions were performed more frequently in women than in men.

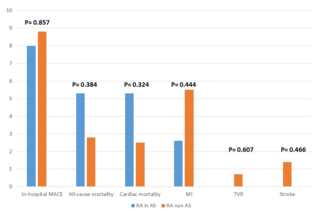

Procedural characteristics (Tables 3 and 4). Mean arterial sheath size and use of a closure device were similar between the two groups. For patients with infrainguinal disease, the anterograde femoral approach was less frequently performed in women than in men (8.8% versus 27.8%; p In-hospital outcomes (Table 5). There were no significant differences in the in-hospital outcomes in terms of lesion success, procedure success, death, stroke or TIA, and contrast nephropathy in women compared with men. Hemorrhagic complications occurred more frequently in women than men (7.4% versus 0.7%; p = 0.006).

All hemorrhagic events occurred at the access site or were retroperitoneal in location. The blood transfusion rate was also significantly higher in women (6.6% versus 0.7%; p = 0.013). Women with an arteriotomy closure device had a lower incidence of bleeding compared to women in whom no closure device was used, although it did not reach statistical significance (3.8% versus 10.1%; p = 0.3). Similarly, no significant difference was noted with the use of arterial closure devices in men (0% versus 2.2%; p = 0.53).

Predictors of hemorrhagic complications (Tables 6 and 7). Univariate predictors of hemorrhagic complications with a p-value Discussion

This study demonstrates that PPAI using contemporary devices and pharmacologic treatments can be performed in women with similar success rates as in men, albeit with over a ten-fold higher risk of hemorrhagic complications compared to men.

Patients undergoing PCI and PPAI have similar risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and smoking.6 Compared to men, women undergoing PCI are noted to be older and have a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as diabetes. In spite of the similar extent of CAD and the procedural success rate compared to men, women have a higher incidence of vascular and bleeding complications.10 This difference has traditionally been explained by smaller body surface area, smaller vessels and older age. Furthermore, patients with PAD undergoing PCI have almost a two-fold higher incidence of bleeding complications.11 Consequently, women undergoing PPAI with or without CAD may constitute a high-risk population for vascular and bleeding complications.

Data on gender differences in outcomes for patients undergoing PPAI who have similar atherosclerotic disease processes and comorbidities are limited, especially in the contemporary device era. Prior angioplasty studies for peripheral arterial interventions predominantly using balloons showed similar success rates between men and women, but with a higher risk for bleeding complications in women.12,13 In these studies, stent and arterial closure device use was minimal, and heparin was predominantly used as an anticoagulant agent.

Patients in our study had several cardiovascular and medical comorbidities such as diabetes, renal insufficiency, along with significant PAD, placing them in a higher risk category for any percutaneous procedure. The peripheral arterial interventions involved several territories, requiring vascular access via different routes, and many devices including stents, in over 70% of patients. Although women had smaller body surface area, a surrogate for smaller vessel size, women had similar lesion and procedural success rates compared to men, which may be attributable to improvement in techniques and devices. In-hospital outcomes were similar between the two groups, although women had over a ten-fold higher incidence of bleeding complications compared to men, a finding no different than patients undergoing PCI for CAD.4,10,14–17Hemorrhagic complications. Vascular and hemorrhagic complications are major causes of morbidity, increased cost after catheter-based interventions, and even death.18 The excessive risk of major bleeding in women in our study was in line with previous studies of PPAI as well as PCI.12–14,17,19 Although the cause of heightened susceptibility to hemorrhagic complications in women is still unclear, several reasons including older age, smaller vessels, sheath size and differing pharmacokinetics of antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents have been proposed.15,16,18,20,21 A prior study has shown prolonged partial thromboplastin time for women given heparin, even after weight-adjusted dosing.21 Less aggressive anticoagulation, or use of a direct thrombin inhibitor, may decrease the risk of bleeding complications. The safety profile of bivalirudin was shown in the recently-published APPROVE trial.22 In coronary intervention with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, on the other hand, a significant interaction between gender and access site bleeding has been suggested.15,16 Because the overall use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors was limited in our study (0.7%), we cannot assess the effect of these agents in PPAI. The role of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in PPAI needs to be evaluated in larger studies.

Interestingly, arterial closure devices were used in almost 60% of our patients after PPAI. Although it has been suggested that women may be at significantly higher risk than men for access site complication with the use of hemostasis devices, such a relation or any protective effect of these devices from hemorrhagic complications were not noted in our study.23,24

Since most of the hemorrhagic complications in our study were rated as major bleeding requiring transfusion, it becomes imperative to closely monitor the use of anticoagulants and antiplatelets agents, along with continued attention to procedural technique.

Study limitations. A major limitation of our study was that it was not randomized, and the data were collected from the single-center database. We believe, however, that this still provides grounds to observe such differences in outcomes in a “real-world population.”

Conclusion

Percutaneous intervention for PAD can be performed in women with similar success rates as in men, albeit with over a ten-fold higher risk of hemorrhagic complications, predominantly driven by major bleeding requiring transfusion. Such a risk in women undergoing any percutaneous intervention calls for special efforts to reduce their occurrence with meticulous care of the access site, selective use of closure devices, less aggressive anticoagulation therapy, and the possible use of direct thrombin inhibitors.

Email: akio.kawamura@lahey.org

1. Jacobs AK. Coronary revascularization in women in 2003. Sex revisited. Circulation 2003;107:375–377.

2. Watanabe CT, Maynard C, Ritchie JL. Comparison of short-term outcomes following coronary artery stenting in men versus women. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:848–852.

3. Jacobs AK, Johnston JM, Haviland A, et al. Improved outcomes for women undergoing contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. A report from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute dynamic registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:1608–1614.

4. Peterson ED, Lansky AJ, Kramer J, et al. Effect of gender on the outcomes of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:359–364.

5. Athanasiou T, Al-Ruzzeh S, Stanbridge RD, et al. Is the female gender an independent predictor of adverse outcome after off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting? Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:1153-1160.

6. Selvin E, Erlinger TP. Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the United States. Results from the national health and nutrition examination survey, 1999-2000. Circulation 2004;110:738–743.

7. Mays BW, Towne JB, Fitzpatrick CM, et al. Women have increased risk of perioperative myocardial infarction and higher long-term mortality rates after lower extremity arterial bypass grafting. J Vasc Surg 1999;29:807–813.

8. Frangos SG, Karimi S, Kerstein MD, et al. Gender does not impact infrainguinal vein bypass graft outcome. Surgery 2000;127:679–686.

9. Roddy SP, Darling RC III, Maharaj D, et al. Gender-related differences in outcome: an analysis of 5880 infrainguinal arterial reconstructions. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:399–402.

10. Chauhan MS, Ho KKL, Baim DS, et al. Effect of gender on in-hospital and one-year outcomes after contemporary coronary artery stenting. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:101–104.

11. Singh M, Lennon RJ, Darbar D, et al. Effect of peripheral arterial disease in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with intracoronary stents. Mayo Clin Proc 2004;79:1113–1118.

12. Krikorian RK, Kramer PH, Vacek JL. Percutaneous revascularization of lower extremity arterial disease in females compared to males. J Invasive Cardiol 1997;9:333–338.

13. Matsi PJ, Manninen HI. Complications of lower-limb percutaneous transluminal angioplasty: a prospective analysis of 410 procedures on 295 consecutive patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1998;21:361–366.

14. Chauhan MS, Kuntz RE, Ho KKL, et al. Coronary artery stenting in the aged. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:856–862.

15. Mandak JS, Blankenship JC, Gardner LH, et al. Modifiable risk factors for vascular access site complications in the IMPACT II trial of angioplasty with versus without eptifibatide. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31:1518–1524.

16. Cho L, Topol EJ, Balog C, et al. Clinical benefit of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade with abciximab is independent of gender: pooled analysis from EPIC, EPILOG and EPISTENT trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:381–386.

17. Trabattoni D, Bartorelli AL, Montorsi P, et al. Comparison of outcomes in women and men treated with coronary stent implantation. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent 2003;58:20–28.

18. Kuchulakanti PK, Satler LF, Suddath WO, et al. Vascular complications following coronary intervention correlate with long-term cardiac events. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent 2004;62:181–185.

19. Waksman R, King SB III, Douglas JS, et al. Predictors of groin complications after balloon and new-device coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 1995;75:886–889.

20. Schnyder G, Sawhney N, Whisenant B, et al. Common femoral artery anatomy is influenced by demographics and comorbidity: implications for cardiac and peripheral invasive studies. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent 2001;53:289–295.

21. Granger CB, Hirsh J, Califf RM, et al. Activated partial thromboplastin time and outcome after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: results from the GUSTO-I trial. Circulation 1996;93:870–878.

22. Allie D, Hall P, Shammas NW, et al. The Angiomax Peripheral Procedure Registry of Vascular Events trial (APPROVE): In-hospital and 30-day results. J Invasive Cardiol 2004;16:651–656.

23. Eggebrecht H, von Birgelen C, Naber C, et al. Impact of gender on femoral access complications secondary to application of a collagen-based vascular closure device. J Invasive Cardiol 2004;16:247–250.

24. Tavris DR, Gallauresi BA, Lin B, et al. Risk of local adverse events following cardiac catheterization by hemostasis device use and gender. J Invasive Cardiol 2004;16:459–464.