Coronary Fistula and Myocardial Ischemia: What is the Relationship?

Abstract: Coronary artery fistula is a rare anomaly; large fistulae may result in myocardial ischemia from coronary steal. We present the case of a 73-year-old male who presented with exertional angina; imaging demonstrated severe coronary artery disease and a large coronary artery fistula. Ligation of the fistula resulted in severe right ventricular failure and cardiogenic shock. After reestablishing flow to the fistula, the patient recovered. We speculate that the ischemia-induced angiogenesis from the congenitally present fistula made what may have otherwise been an innocent fistula into an important nutritive supply, which remained important despite distal revascularization. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing the critical nutritive value of a coronary fistula.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2016;28(11):E134-E135

Key words: coronary artery fistula, coronary artery disease, revascularization

Case Presentation

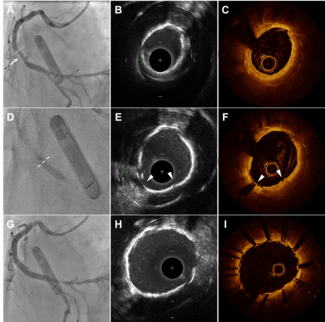

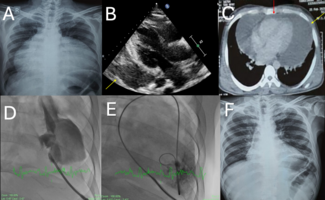

Coronary artery fistula (CAF) is a rare anomaly; large fistulae may result in myocardial ischemia from coronary steal.1 Symptomatic patients are treated by percutaneous closure.2 A 73-year-old man presented with exertional angina. Coronary angiography demonstrated severe three-vessel disease (Figures 1A and 1B), and a large proximal CAF originating from the right coronary artery draining into the right ventricle (Figures 1B and 1C).

Surgery was performed with cardiopulmonary bypass but without aortic cross-clamping due to extensive aortic plaque. After left internal thoracic arterial anastomosis to the left anterior descending coronary artery, the fistula was ligated proximally. Three saphenous venous grafts including one to the posterior descending artery were constructed. The CAF was used as the inflow for these grafts as there was no suitable location on the aorta for the proximal anastomoses (Figures 1E and 1F). When we attempted to wean the patient from bypass, he developed severe right ventricular failure and cardiogenic shock. We surmised that the fistula ligation had caused the right ventricular dysfunction, and thus reestablished flow to the fistula by performing a side-to-side anastomosis with the venous graft to the CAF distal to the point of ligation, after which the patient weaned without difficulty and made an uneventful recovery.

We speculate that the ischemia-induced angiogenesis from the congenitally present fistula made what may have otherwise been an innocent fistula into an important nutritive supply, which remained important despite distal revascularization. Our case emphasizes that not all fistulae need to be closed, especially if they are not resulting in symptoms or chamber dilation, and it is paramount to perform an occlusion test to assess for myocardial ischemia prior to definitive intervention.

To our knowledge, this is the first report describing the critical nutritive value of a coronary fistula. It is unknown whether CAF in the presence of underlying obstructive coronary disease subtending the same territory is a risk factor for the described phenomenon.

References

1. Latson LA. Coronary artery fistulas: how to manage them. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70:110-116.

2. Jama A, Barsoum M, Bjarnason H, Holmes DR Jr, Rihal CS. Percutaneous closure of congenital coronary artery fistulae: results and angiographic follow-up. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:814-821.

From the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Disclosure: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Manuscript submitted May 14, 2016, and accepted June 1, 2016.

Address for correspondence: Dr Maral Ouzounian, Toronto General Hospital, 585 University Avenue, Toronto, ON, M5G 2N2 Canada. Email: maral.ouzounian@uhn.ca