Feature

Case Presentations and Discussions (Cases 3 and 4)

March 2003

CASE #3

Jeffrey Popma, MD

Let me begin by talking about our new catheterization laboratory table that accommodate patients up to 600 lbs. Everyone should get one of these tables because it will allow you to receive some incredible patient referrals in the middle of the night! I handled a case involving a 46-year-old man who weighed 490 lbs. The calculations of this new cath lab table add up to 600 lbs. for CPR, so a 200 lb. patient leaves an additional weight limit of 400 lbs. Thus, when this 490 lb. patient arrived, we had our 90 lb. technologist available in the lab in the event that CPR was needed — an arrangement that would have kept us under our weight limit!

The patient presented with an inferior infarct and received aspirin and reteplase at a hospital in Worcester, located approximately 50 miles from our institution. He did not improve and was transferred to us. At that point, the patient was 12 hours from the onset of chest pain which he was still experiencing. There was no access to anything in the patient’s groin; we couldn’t even find the anterior superior iliac crest. He had already had a tracheostomy for sleep apnea, his heart rate was 50 and his blood pressure was 100/16. He didn’t look very good. I used the radial approach and found that his circumflex artery was totally occluded and there were lesions in his LAD and RCA — thus, three-vessel disease.

It was 3:00 am and I said to myself, “I am out of here!” I then called one of Dr. Aranki’s partners and told him I had a great case for him: three-vessel disease; clot in two vessels; the patient was as sick as can be; he failed lytics — he was just perfect. While Dr. Aranki’s partner was getting out of bed, he asked if there was anything else he needed to know about the patient. I told him that the patient weighed 490 lbs. and had a trach in place. Dr. Aranki’s partner said, “That doesn’t sound very good. I’ll never get him off the vent later, so he’s all yours.” The patient was still experiencing chest pain and was turned down for surgery. Sari, would you have taken him? You weren’t on duty that night, but I wonder what you would have done with this patient.

DISCUSSION

Sari Aranki: That is one question I don’t want to answer!

Spencer King: But all of our insides are the same size — like corn dogs!

Sari Aranki: Most of these patients end up on on a ventilator, and with a trach in place, the outcome could be disastrous.

Jeffrey Popma: Right. That was your partner’s opinion as well. But I have a practical question: How do you dose clopidogrel in a 490 lb. patient? Is it the same? And what about GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor dosing?

James Tcheng: I like Spencer’s corn dog analogy about all of our insides being the same size! There is ongoing work with GP IIb/IIIa agents to analyze dosing relative to weight. It looks like intravascular volume does not increase very much as external mass increases. The clinical trials have been weight-limited between approximately 130 and 140 kg. The package inserts all indicate up to approximately 140 kg and end there — and not to dose higher based on weight. I don’t have an answer to the clopidogrel question. This highlights the need for an accurate point-of-care bedside assay. At least at Duke University we can use the Accumetrics device. But in terms of the dose response to clopidogrel, I don’t know the answer.

Jeffrey Popma: As Spencer said, there is probably no downside to giving megadoses of these agents — 525 mg or 600 mg. The margin of safety is probably much larger in the case of an obese patient.

James Tcheng: Antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel, IIb/IIIa agents, aspirin), unlike most therapeutic treatments, does not appear to have a therapeutic window in terms of efficacy. If there is any question about dosing, I would lean toward giving more.

Jeffrey Popma: I placed a pacemaker in this patient’s neck because I thought his heart rate was slow already and as I mentioned, he was a surgical turn-down. The only bad part about doing that is that you have to cine to fluoro when you have a large patient; you can’t even see to put your equipment down. Ultimately, I stented the right coronary artery, but he still had persistent pain. The patient’s EKG improved, then I injected the LAD. However, the patient’s condition seemed to be deteriorating. The clot looked a little worse even though we had given him aspirin and a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor. He hadn’t received clopidogrel yet, but it was on the way. I ended up stenting the LAD as well. I had thought about treating the patient’s chronically totally occluded circumflex, but it was 5:00 am and I decided to stop there. The patient felt much better. My question is: Is a dose adjustment needed for this patient? The standard dose is 75 mg, but should a 490-lb. patient be given more clopidogrel? Does anyone have any thoughts about that for chronic therapy? Are there any large patients in the CREDO trial?

Shamir Mehta: The patient needs a bypass, just not a coronary bypass!

Jeffrey Popma: There is some heterogeneity in terms of how we all practice. Under ideal settings, Chris, what would you recommend for acute coronary syndromes at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital?

Chris Cannon: There seems to be a disconnect between the stented lesion and everything else — the CRP and the multiple plaques and the diffuse nature of things. The acute therapy and the long-term therapy actually involve two different parts of the coronary anatomy. Ron, in terms of long-term treatment post-radiation, is there benefit for the radiated segment or do the other areas of the coronary tree benefit?

Ron Waksman: I think that there is benefit for everything. A reduction of events across the board has been observed, not just in the lesions themselves. Though this is a small registry, I would bet that it resembles what the CREDO results will show because it was not just for that specific segment.

Jeffrey Popma: Let me present the following scenario: You are in the middle of a radiation case, things don’t go so well, some recoil occurs, so you place a stent. Some of my partners have been stopping at that point, not going on to perform radiation brachytherapy because they have to place one or two stents. I try to argue — and I don’t know if this correct — that they should just go ahead with the brachytherapy, make sure the margins are adequate, and give the patient clopidogrel. Am I being too cavalier about that?

Ron Waksman: No, I think you are right. The only issue I have is with patients whom we feel won’t comply with the drug regimen long-term. Unfortunately, we just had a patient today on whom we were not sure we could perform brachytherapy treatment because he did not have insurance to pay for twelve months of clopidogrel. Also, the thromboses that have occurred were in patients who stopped the clopidogrel ahead of time. We have to take these patients into account because that’s part of the game. When we commit patients to twelve months of clopidogrel, there will be some who stop because their general physician or dentist advised them to or because they ran out of money, insurance coverage, and so forth. Twenty-five percent of our patients are still receiving stents and radiation. Also, some other small studies have shown that we can stent and radiate at the same time, but we must be careful about prolonged antiplatelet therapy. We seem to be overlooking the fact that the benefit between six-month and the twelve-month therapy is not necessarily a reduction in thrombosis rates, but a reduction in overall event rates.

I have another unrelated point to make regarding the loading dose issue that Jeff brought up. I was impressed by Dr. Hacker from Emory who said at the time that a much higher loading dose than 300 mg is needed for some patients. Patients occasionally present after two or three days with subacute thrombosis despite clopidogrel treatment. I wonder if these are the patients who could have benefitted from a larger dose — because they started their treatment at the time of their elective procedure. The message is not clear about what the loading dose should be in these cases.

Shamir Mehta: Some studies have looked at platelet inhibition in a test tube and there are some limited data on higher doses in clinical situations. Generally, these data show that the benefit is roughly the same, but there is actually an increase in bleeding as the dose exceeds 375 mg. Thus, there is a trade-off. Patients who receive a higher dose of clopidogrel should be carefully selected, but a 300 mg dose should be sufficient for the vast majority of patients.

James Tcheng: Unfortunately, it’s not the vast majority we worry about, it’s the few percent of patients who are clopidogrel-resistant, or are grossly overweight, or have polymorphism, or some type of mutation that makes them different. We need an affordable, predictive test for dose response to clopidogrel.

Spencer King: It sounds to me like the patients who have experienced late thrombosis have stopped their medication for one reason or another.

Jeffrey Popma: In January or February, the drug-eluting stents will be available. I think many of us will be tempted to use these stents to treat in-stent restenosis. The data from the Serruys series using the Cypher stent for in-stent restenosis show that the late events occurred in patients who were no longer on clopidogrel. What do you think about that, Steve?

Stephen Ellis: Certainly, the more diffuse the disease the more likely clopidogrel should be given indefinitely. By diffuse I mean both angiographically and from the standpoint of diabetes and elevated inflammatory markers. I would be inclined to give clopidogrel for at least one year based on the clinical data.

Spencer King: I wonder if we could treat both ends of the stent, though it would be an expensive proposition because it would require two of them.

Jeffrey Popma: Or perhaps one long stent. Let’s move on now to Deepak’s case presentation.

CASE #4

Deepak L. Bhatt, MD

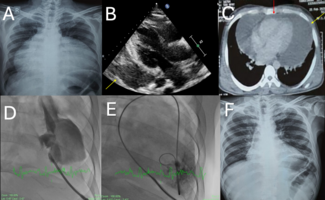

This case involves an 81-year-old male who had recently been hospitalized for heart failure and was admitted with rest chest pain associated with epigastric discomfort, left arm pain, dyspnea, and nausea. The patient had experienced a rather large anterior wall myocardial infarction sixteen years earlier which he remarkably survived. I wasn’t involved with his care at that time, but he had received a vein graft to the right coronary artery and a ventricular aneurysmectomy. The patient also had a history of a TIA and underwent a left carotid endarterectomy five years ago. His ejection fraction was last known to be 20% and he had symptomatic heart failure. The patient also had a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. On physical exam, the patient had JVD, rales halfway up bilaterally, initial regular heart rate and rhythm, an S3, a 2 out of 6, holosystolic murmur, positive bowel sounds, and no evidence of a AAA. He also had bilateral femoral bruits and no peripheral edema. Medications at the time of the initial evaluation included digoxin, furosemide, quinapril, pravastatin, metoprolol, and aspirin. His initial laboratory results were notable for a creatinine of 1.6, a B.U.N. of 37, a hemoglobin of 12.8, elevated troponin-I, elevated BNP, and an LDL of 90. The initial EKG showed a normal sinus rhythm at 80; there was an old left bundle branch block; first degree AV block; and poor R-wave progression that was also old. The patient underwent an echocardiogram soon after presentation which showed global left ventricular dysfunction with anterior and apical scarring, a dilated left ventricle, no visible thrombus, and an ejection fraction that was again estimated to be 20–25% with at least 2+ mitral regurgitation. The patient was initiated on clopidogrel, enoxaparin, and eptifibatide. I invite your comments about whether this was the appropriate treatment for this patient.

DISCUSSION

Chris Cannon: The treatment choice followed the guidelines.

Deepak Bhatt: Yes, but the guidelines don’t really provide much in the way of guidance to fuse these different forms of therapies. That is, the guidelines say that clopidogrel is terrific; enoxaparin is better than unfractionated heparin; upstream GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors are great, and so forth.

Chris Cannon: The guidelines instruct us to use these agents, but there are some missing pieces in the data, particularly concerning clopidogrel and eptifibatide pre-catheterization.

Sari Aranki: This patient is having a myocardial infarction. We take post-CABG patients who are having a myocardial infarction to the catheterization laboratory.

Shamir Mehta: This is a high-risk patient who should go to the catheterization laboratory.

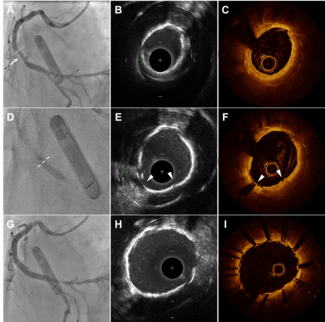

Deepak Bhatt: I would not disagree with that. Actually, it was at this point that I was introduced to the patient who had been transferred to us from the original cardiologist. The angiogram, which I will show you in a moment, revealed a left anterior descending artery that was occluded very proximally; his native right coronary artery had a 100% occlusion; his circumflex was actually fine and was a reasonably sized vessel, though not a dominant one. The saphenous vein graft to the right coronary artery, which was the one graft he received 16 years earlier, had two severe lesions with angiographic evidence of thrombus (Figures 1 and 2). The left ventricle appeared severe and his diastolic pressures were elevated. As you can see, there are two severe lesions which are bound in on either side by thrombus. What would you recommend doing with the patient at this point?

Stephen Ellis: Was the patient still experiencing angina?

Deepak Bhatt: The patient was still experiencing a fair amount of discomfort as well as dyspnea. It was because of the combination of his symptoms that he was transferred to our hospital.

Jeffrey Popma: Could you place a balloon pump in the patient’s other leg if needed?

Deepak Bhatt: The patient had bilateral femoral bruits and no femoral angiography had been performed. He did have palpable pulses on both sides but poor distal pulses. If I recall correctly, PT and DP were not palpable, though his feet were warm and appeared well perfused.

Jeffrey Popma: But clinically, the patient was in congestive heart failure; he had rales halfway up bilaterally.

Deepak Bhatt: Yes, he was able to speak on about 4–6 liters. His oxygen saturation was satisfactory, but he did have some dyspnea at rest and rales halfway up bilaterally.

Jeffrey Popma: The patient was already in heart failure with an ejection fraction of 20%. If an intervention was going to be performed, I would probably try to place a balloon pump in the patient ahead of time. Steve, what do you think about a balloon pump in this patient?

Stephen Ellis: I think it would be a great idea. I would actually consider sending this patient to surgery because there is nothing to be done to keep a 16-year-old vein graft open a couple years longer at this point.

Mercedes Dullum: I agree that surgery would be a high-risk venture. The mitral valve problem would be something to decide about as well. An 81-year-old patient with that ventricle — is it due to the dilated cardiomyopathy? Since the patient had no circumflex lesion, he was probably not experiencing acute mitral regurgitation. We would operate on the patient, but I think that his outcome would be better if there was some way to “cool him down” before surgery.

Sari Aranki: I would place a balloon pump in this patient if possible and perform a left trunk CABG from a left thoracotomy and work on the LIMA to the LAD, and the vein graft to the PDA. If the patient was still in trouble two days after that because of his mitral problem, I would consider doing a right thoracotomy mitral valve if his femoral arteries were in good shape.

Jeffrey Popma: I assume, Deepak, that this patient did not go to surgery.

Deepak Bhatt: No, he did not. I thought about doing all of those things, but the patient was referred to me specifically for an interventional approach, so I was focused on the interventional options.

Stephen Ellis: I assume that the native vessel was totally occluded but was not approachable.

Deepak Bhatt: That is a good point. I didn’t include a picture of the native right coronary artery, but it was stumped proximally so there was really no possibility of recanalizing it.

Spencer King: Did you consider the possibility of administering fenoldopam or something like that?

Deepak Bhatt: We actually did give the patient a dose or two of Mucomyst, both before the procedure and afterward.

Spencer King: It was too late for Mucomyst in that situation.

Chris Cannon: We have been very aggressive with fenoldopam use at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and it seems to be quite effective. We are waiting for the data from the study, however.

Spencer King: The fenoldopam study is almost completed and it will be interesting to see what the results show.

Deepak Bhatt: We have not yet begun routine use of fenoldopam at our center, but it might be something we will do in the future. We imaged the patient’s femoral system. He had severe plaque on both sides, including the side we had accessed through the groin. His infra-renal abdominal aorta was a bit aneurysmal, so we elected not to place a balloon pump, although it was considered. Instead, we opted to place a Percusurge (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn.) occlusion balloon distal to the second of the two lesions (Figure 3).

Jeffrey Popma: I have a hypothetical question for Steve regarding this patient: The LAD is out, the circumflex artery is basically fine, although it’s a hyperdominant right. Let’s say it is one year from now: What do you think about a filter versus a balloon occlusion device for this situation?

Stephen Ellis: The lesion looks so bulky that I think the net effect would be the same with both devices. The primary advantage with filters is that you can see what you are doing and the patient has less ischemia during the procedure. However, with significant debris, the filter is going to fill up so quickly that it may occlude flow right then and there. I am not terribly happy with the Percusurge data in this situation because while there was a 12–15% reduction in the event rate, it is 20–30% at baseline. Perhaps some sort of combination of these devices would be the best approach to take (e.g.: filter plus aspiration).

Jeffrey Popma: Having used this device a couple of times I have found that there must be replacement flow. If the X-port catheter (PercuSurge, Medtronic, Santa Rosa, CA) is totally occluding the distal vessel, thrombus cannot be removed because there is no way to replace it. The AngioJet® (Possis Medical, Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.) device offers the advantage of replacement fluid that allows the material to be sucked out. In this case, there may well have been flow around the export catheter to suck the thrombus out, but if not, the AngioJet would be a great tool.

Deepak Bhatt: We decided to use a combination of the Percusurge and AngioJet devices (Figure 4). I was a little worried about inflating the Percusurge balloon and occluding flow, and I was not sure how well the patient would tolerate it in such a complex procedure. I did place a temporary pacemaker in the right ventricle apex. I would have considered using a filter if it had been commercially available for this indication. In fact, just last Friday, I used an AngioGuard (Cordis Corp., Miami Lakes, Florida) filter — not for a coronary case, but for a carotid case in which there was a 99% stenosis and a high degree of plaque volume which totally filled the filter completely and occluded flow. Thus, I think Dr. Ellis’s point is a good one: If a filter had been placed in this patient, it would probably have just clogged up and created a stagnant column of blood. I proceeded to place a stent in the distal lesion with the Percusurge device. Of course, I used hemostats and bony landmarks to determine where to position these stents. I slightly oversized the balloons and the stents in terms of length because I didn’t have the benefit of any contrast dye. I then used the AngioJet once more.

Mitch Driesman: Did you use regular or drug-coated stents in this patient?

Deepak Bhatt: That is a good question. I just used bare-metal Bx Velocity™ stents (Cordis Corp., Miami Lakes, Florida) in both of the lesions (Figures 5 and 6). This image shows the final result.

Mitch Driesman: You used the AngioJet twice. Did you also use the catheter again?

Deepak Bhatt: No. The AngioJet was used both prior to any stent deployment and then again afterwards (Figure 7).

Mitch Driesman: What was the total time that the PercuSurge device was left in the artery?

Deepak Bhatt: The total time was eight minutes. I had a very seasoned interventional Fellow working with me on this procedure, so we were able to complete the job relatively quickly. The patient tolerated the device reasonably well. A pacemaker was in place, so his rhythm was quite stable. The patient did begin to get hypotensive toward the end of that eight-minute time period, however, and I wished at that point that we had placed a balloon pump in anyway — maybe a lower-profile balloon pump — despite the patient’s vascular disease and the angiographic evidence of an aneurysm. Fortunately, the patient managed to survive the procedure and actually did quite well in the short-term (Figure 8). We then needed to decide what to do in terms of long-term management. This image shows that there was no embolization in the distal vessel (Figure 9). It seems that the issues are somewhat similar in terms of long-term management: the role of clopidogrel and the duration of its use; the appropriate aspirin dose for the chronic phase of therapy; and perhaps secondarily, a short course of enoxaparin as an out-patient to help dissolve any other thrombus that may not have been angiographically apparent.

Chris Cannon: I would not recommend enoxaparin therapy. This patient has had prior CABG and would benefit significantly from clopidogrel, which is a marker of diffuse disease. The general consensus from this meeting is that the worse the disease, the longer the clopidogrel treatment should be — whether the patient has had radiation therapy, prior known disease, acute markers, and so forth. I think that this particular patient should be given 325 mg of aspirin acutely, with a dose reduction if he stabilized.

Spencer King: What we need is a three-year study that focuses on vein graft interventions because historic data recommend one therapy, but things will change again in a couple of years. Could clopidogrel bail us out here on some of these old vein grafts?

Deepak Bhatt: I opted to advise the patient to remain on lifelong therapy of 81 mg of aspirin a day and clopidogrel. He had no history of prior bleeding problems and I wanted to do everything possible to keep that vein graft open. As it turned out, I also consulted the electrophysiology doctors because his left ventricle was quite dysfunctional. The patient had experienced a recent myocardial infarction, thus the EP doctors elected not to place an ICD. It was their opinion that the patient’s overall longevity and mortality would not justify an ICD. We also performed another better echocardiogram which revealed his mitral regurgitation to be worse than we thought, but the surgeons did not want to touch this patient. In terms of symptoms, the patient was doing well. He was able to ambulate and was discharged from the hospital. The patient is now being medically managed and is doing well in the short-term.

Jeffrey Popma: Sari and Mercedes, are there circumstances where patients undergoing just a routine CABG procedure or an endarterectomy receive long-term aspirin and clopidogrel? Do you have any patient subsets for which you give extended clopidogrel?

Mercedes Dullum: I primarily work on beating hearts, and all of my beating heart patients do receive about a six-week course of clopidogrel post-CABG. We also keep our endarterectomy patients on clopidogrel post-op. We have some data, though not risk-stratified, that suggest a trend toward a reduction in mortality when clopidogrel is given to patients post-op.

Chris Cannon: Was this the case for the endarterectomy patients as well?

Mercedes Dullum: No. This was for the patients on clopidogrel versus no clopidogrel. But since these data are not risk-stratified, they need closer scrutiny.

Jeffrey Popma: I will wrap up this round table meeting now with a few final comments. I am impressed with the fact that such a wealth of data are available today compared to only a year or two ago — and even more data will be available when the CREDO trial results are presented. The treatment guidelines have been formulated according to solid evidence-based medicine. But I will bet that if we looked closer, we would find that less than half the patients — probably 20–30% — are really on nine months of clopidogrel therapy. We need to incorporate the data currently available and those from CREDO and begin conferring more with one another and with our referring physicians to determine exactly which subsets of patients benefit from clopidogrel. We know that there may be up to a 50% reduction in clinical events with the use of extended clopidogrel therapy in the patients we currently treat with drug-eluting stents and radiation brachytherapy, and those with complex disease, and vein graft disease. Thus, if we put patients on clopidogrel for three to six months after placing a drug-eluting stent, why stop it then?