Feature

Case Presentations and Discussions (Cases 1 and 2)

March 2003

CASE #1

Jeffrey Popma, MD

I prepared several case presentations because I wanted to use the panel assembled here this evening to tell me how to take care of my patients when I return home. You will all therefore be interrogated on how to best treat these patients!

This first case involves a 54-year-old male who was in good health. He presented to the emergency department following three days of stuttering chest pain. The patient’s ST-segment depression appeared in 2, 3, and AVF, and his troponin was slightly elevated. What would you do with this type of patient according to your institution’s clinical pathways protocol? Two scenarios will be considered here. The first scenario involves an institution that is equipped with a very active on-site catheterization laboratory. The second scenario involves no on-site catheterization laboratory. The questions regarding treatment options are: clopidogrel versus no clopidogrel; low-molecular weight heparin versus unfractionated heparin; and IIb/IIIa inhibitor versus no IIb/IIIa inhibitor in the emergency department.

DISCUSSION

Jeffrey Popma: Mitch, what happens in the emergency department at your institution? You have a catheterization laboratory; a patient in the emergency department is hot; what do you do?

Mitch Driesman: What time of day is it?

Jeffrey Popma: Let’s say that it is 4:00 pm, so you still have plenty of energy left.

Mitch Driesman: At my institution, I would definitely make sure that the patient is on aspirin and I would load him with 300 mg of clopidogrel. If the cath lab was not immediately available, I would start the patient on a IIb/IIIa inhibitor. If the cath lab was available, the patient would be started on a IIb/IIIa agent in the cath lab. And since it is 4:00 pm, the patient would likely be taken immediately to the cath lab. I would probably still use standard unfractionated heparin because it’s simple to use and can be measured with our standard ACT machines.

Jeffrey Popma: Mercedes, does it bother you at all that Mitch would be starting the patient on clopidogrel — because this patient could have surgical disease in which case you would probably want to operate on him while he’s at the hospital instead of waiting five days.

Mercedes Dullum: If the patient needs surgery, then he needs surgery; I would just deal with the situation.

Jeffrey Popma: But how do you just deal with it?

Mercedes Dullum: These patients frequently end up receiving a platelet transfusion and some blood, if needed. We have looked at our numbers and found a three-fold increase in re-operation rates on these types of patients, but we normally go ahead and operate on them. We have also looked into whether the patient can wait — which probably is not the case here — by determining whether bleeding times are > 15 minutes. In general, however, we have been taking these patients to surgery because we think there is an added benefit to doing so.

Jeffrey Popma: Sari, you operate on many of our patients who fit this profile. Would you rather we hold off on administering clopidogrel to these patients, or administer it — or does it not matter very much? We have to perform catheterization on these patients to define their anatomy before they go on to surgery; it’s a fundamental rule! Sari is a surgeon and he would prefer to take these patients to the operating room and fix the problem rather than having them go to the cath lab first. We have very aggressive surgeons here!

Sari Aranki: We must be careful when we talk about bleeding, especially after clopidogrel administration. Most of these patients are given integrilin and are likely to have a longer bypass surgery which in itself can cause anticoagulation problems afterwards. Thus, I don’t know how people can just blame one therapy or another for the excessive bleeding that occurs or for the need for transfusions.

Jeffrey Popma: Let’s vote on how many would administer clopidogrel in the emergency department — knowing the patient is going to the cath lab — versus how many would wait to give the patient clopidogrel until after catheterization. The opinions are split on this according to your show of hands. Patients go on to surgery approximately 10% of the time, so it is a low-risk issue. I am surprised, however, that there is still this impression that the bleeding complication rate may be higher in the acute setting. At our institution, we tend to wait until after the catheterization procedure to administer clopidogrel to the patients in this scenario.

Chris Cannon: At our institution, it depends on who the attending physician is in the cardiology service that day!

Sari Aranki: What percentage of the patients in this scenario actually go on to receive bypass surgery the same day? It doesn’t matter whether clopidogrel is administered in the emergency department, in the catheterization laboratory, or afterwards.

Jeffrey Popma: Yes, that’s true. Steve, what are you doing at the Cleveland Clinic?

Stephen Ellis: It’s a mixed bag. I still don’t completely understand the data in terms of whether it makes a difference to give the patient clopidogrel after the diagnostic angiogram, or whether I can wait an hour or so after treating the patient in the catheterization laboratory. We need the CREDO results.

Jeffrey Popma: Right. I don’t know either.

Chris Cannon: We will find out tomorrow!

Spencer King: I don’t know if it has the same affect as 300 mg, but in studies on volunteers, a 525 mg dose achieved steady state inhibition quicker than 300 mg.

Jeffrey Popma: If the patient has a IIb/IIIa inhibitor on board, our biggest hit for CK-MB elevations is when the balloon or stent is placed — that is the moment when it happens. If we are trying to prevent an ischemic event at the remote site or a subacute thrombosis, I don’t know if an hour really matters all that much.

Dr. Rapaport, what pharmacological regimen would you recommend for acute coronary syndrome patients in an emergency department that does not have immediate access to a catheterization laboratory?

Elliot Rapaport: If there is no immediate access to a catheterization laboratory, I would administer low-molecular weight heparin. For the patient in this particular case, however, I would start with unfractionated heparin and take him immediately to the catheterization laboratory. All patients would receive aspirin and beta-blockers before they actually go to the catheterization laboratory as well. Since this is a high-risk patient, the ideal therapy would involve taking him directly to the catheterization laboratory. In this case, I am assuming that the patient would be transferred to a center where a catheterization laboratory was available and I would definitely administer clopidogrel before transferring him. If there was going to be a significant delay, I would also start the patient on a IIb/IIIa inhibitor — but not abciximab. Then I suppose I would play it by ear.

CASE #2

Jeffrey Popma, MD

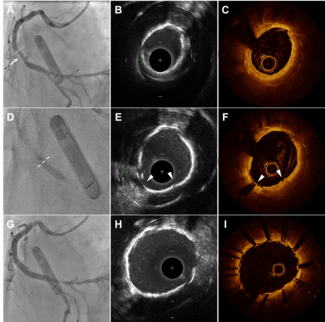

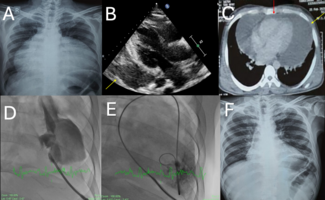

This patient, as you will see, has a fairly normal left coronary artery. However, he has an extremely hyperdominant right coronary artery. We gave the patient aspirin and unfractionated heparin. We did not load him with clopidogrel in the emergency department, but it would certainly be administered afterwards. You can see that there is clot and ugliness here within the vein graft.

Steve, would you do anything other than just place a bunch of stents in this vessel?

DISCUSSION

Stephen Ellis: I would consider placing an embolic protection device in the vessel. I would also consider whether the patient might be better off on a IIb/IIIa inhibitor overnight until he stabilized. All in all, I think I would plunge ahead with stent placement after treating the patient with as much antiplatelet and anti-inflammatory agents as possible. I realize that the jury is still out on the use of embolic protection devices in this scenario, but it certainly would cross my mind to use one.

Jeffrey Popma: Jim, what do you think?

James Tcheng: Did it look like there was a significant amount of thrombus?

Jeffrey Popma: Yes, it was very hazy within the vessel.

James Tcheng: The seminal work of the PRISM-PLUS trial with tirofiban showed that 48 hours of pre-treatment with tirofiban was associated with a reduction in the thrombus burden. Furthermore, treatment with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors and clopidogrel will reduce the no-reflow phenomenon, distal embolization, and so forth. One possible treatment approach for this case, depending upon the thrombus burden, is to actually stop there and load the patient with clopidogrel and a GP IIb/IIIa agent. We would put this patient on enoxaparin as well and keep him in the hospital for 48 hours to try to reduce the thrombus load. This is a young patient with a hyperdominant right coronary artery. The last thing you want in this case is for no-reflow to develop in the vessel. A fair proportion of my colleagues at Duke would stop right there and put the patient back on the floor.

Mitch Driesman: What is the risk/benefit in terms of groin complications by pulling out the sheath, putting in another sheath in 48 hours, and/or potential closure over that 48-hour period versus reducing the risk of no-reflow?

James Tcheng: We do this fairly frequently at our institution, perhaps because we are located in the deep South where we tend to be conservative in our management approaches and because we fear thrombosis. The groin really has not been a concern; it’s the thrombotic complications that might result with moving forward to intervention that need to be prevented. You can always fix the groin, but it’s more difficult to fix the heart once a complication has occurred.

Jeffrey Popma: We agreed with all of that, but I wanted to do something different in terms of embolic protection using the Percusurge device. I used the X-port catheter first to perform the thrombectomy, rather than hook an AngioJet to it. I removed the clot as shown here. It was red clot the first time around — a thrombotic occlusion. This slide shows what it looked like immediately afterwards. Next, I went back up with a Percusurge balloon and then stented the lesion. The patient was then loaded with clopidogrel in the recovery unit and will, without question, remain on clopidogrel long-term. Perhaps I got lucky with this case.

How many of you are dropping the dose of aspirin at 30 days based on the CURE subset data which show lower bleeding complication rates? I actually began doing that; after 30 days, I have been dropping the aspirin dose to 81 mg and have been quite impressed with the results.

Chris Cannon: Shamir, have you had the opportunity to study the PCI-CURE aspirin dose data, because I realized that there will be some patients mixed in the PCI group?

Shamir Mehta: No, we have not looked specifically at PCI-CURE, but it is certainly something we could do.

Stephen Steinhubl: In the CREDO study, all patients are receiving 325 mg of aspirin at 30 days, whereas in CURE, dosage was left to the discretion of the investigator.

Jeffrey Popma: How long? Nine months at least? We would give it longer for some of these patients, even those with single-vessel disease.

Spencer King: It hasn’t been well studied, but this is a vein graft; you’re never going to cure it with a drug when there’s distal emboli. We need a study on that, but it’s difficult for me to imagine that anything will protect the patient completely in that scenario. Perhaps we could give the patient the drug and come back a few days later, but then you’ve got to bite your fingernails for three days worrying about the vessel closing up. And then you develop an ulcer and have to treat that!