Patient Recall and Satisfaction of EHR Content

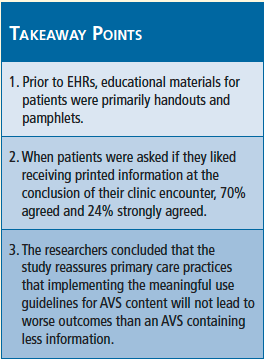

Prior to electronic health records (EHRs), educational materials for patients were primarily handouts and pamphlets; however, EHRs now allow clinicians to supply patients with individualized information in the form of an after visit summary (AVS) based on data available in their medical records, according to a recent study [J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(2):209-218].

According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the minimum set of elements recommended to achieve stage 1 meaningful use of an AVS include:

• Patient name

• Provider name

• Date and location of visit

• Reason(s) for visit

• Vitals

• Problem list/current conditions

• Medication list

• Medication allergies

• Diagnostic tests/laboratory results

• Patient instructions

The researchers developed a 2-phase study to identify the best way to format and utilize the AVS feature in order to: (1) understand through qualitative research the design features that patients and clinicians viewed as important; and (2) test in an individual-level randomized trial whether various salient features of the AVS identified during the qualitative phase affected important patient outcomes, including recall of the general AVS content, medication recall, satisfaction with the AVS, patient use of the AVS, and self-reported adherence to physician instructions.

To test whether variations in the amount of information included in the AVS would affect the specific outcomes, 4 experimental versions were developed: 1 version included all elements necessary to meet CMS meaningful use requirements; 2 versions containing reduced amounts of information; and a final version containing the usual AVS already in place at the given clinic.

The study was conducted in 4 clinics, all of which were part of the Southern Primary-Care Urban Research Network, providing a sample of 68 participants in each of the 4 experimental AVS groups (272 total participants), with approximately equal numbers of English- and Spanish-speaking patients. Patients were recruited before a physician visit; after consent, patients underwent a short interview and literacy assessment and were randomized to 1 of the 4 study groups. Eligible patients were 21 to 75 years of age with 1 previous visit to the clinic and at least 1 chronic health problem requiring medication recorded at the previous visit. Across all clinics, routine printing and delivery of an AVS to patients after their clinic visit was inconsistent.

Data were collected on how patients used the AVS after the office visit via telephone interviews, in the patient’s preferred language and was conducted 1 to 3 days and 14 to 21 days after the clinic visit to measure short-term and long-term recall uses of the AVS. Patients were questioned on general AVS content and medication recall, as well as satisfaction with the AVS.

All 272 patients completed the short-term follow-up interview; 212 patients completed the long-term interview. Of the participants involved in the study, 75% were female, 64% had adequate health literacy, and the average number of prescribing medications was 5.8. The highest percentage of categories recalled, out of total number of categories on their version of the AVS, was observed in the group with the shortest AVS; this percentage (32%) was still considered to be relatively low.

When patients were asked if they liked receiving printed information at the conclusion of their clinic encounter, 70% agreed and 24% strongly agreed. At the time of the first telephone follow-up, 12.5% of participants reported they had read the AVS at least once and 51% said they had filed it with their other health records.

Limitations of the study included the inability to manipulate several features, including language and reading level, and omit certain categories of information from AVSs generated in the context of an actual clinic visit, resulting in AVSs that were not significantly different across the experimental groups. A strength of the study existed in the randomized design that controlled for potentially important cofounding factors.

The researchers concluded that primary care patients liked to receive an AVS, but the length of the summary resulting from current CMS meaningful use does not adversely affect a patient’s recall or satisfaction when compared to shorter versions containing less information. There is concern that much of the information presented in the AVS is disregarded or not retained. To address this issue, the researchers suggest implementing “closing the loop” when the AVS is provided, in which the patient repeats back important information conveyed during the visit.

Overall, the researchers concluded that the study reassures primary care practices that implementing the meaningful use guidelines for AVS content will not lead to worse outcomes than an AVS containing less information.