Medicaid Tackling Social Determinants to Improve Outcomes

Lacking stable housing, access to nutritious food, transportation to medical appointments, or just plain isolation or loneliness are factors that often set people up for poor health conditions. Whether it is not adhering to prescribed medications or relying on emergency rooms to manage chronic conditions, lack of access to the basic social needs of living makes it difficult and sometimes impossible for people to manage chronic illnesses, much less prevent them. The impact on individual health and increase in health care costs are the inevitable consequences of ignoring these nonclinical or social determinants of health.

A report recently published by the Institute for Medicaid Innovation highlights the negative impact of unmet social needs on the overall health of Medicaid populations. For people enrolled in Medicaid, despite many having full-time jobs, low income is an underlying driver of not having access to social needs deemed important to health. Among the social needs affecting the Medicaid program highlighted in the report are low education (36% of persons covered by Medicaid have less than a high school education), lack of access to transportation, living in difficult social contexts (high-stress environments or violent social interactions or behaviors linked to chronic disease such as smoking or substance abuse), housing insecurity, food insecurity, and poverty.

In its introduction, the report cites data highlighting the need if not the mandate to address these social determinants. Evidenced showed that 60% of preventable mortality is attributed to nonclinical factors, including environmental, political, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors. Only 10% to 15% of preventable mortality in the United States is influenced by clinical care.

For managed care plans that manage state Medicaid programs, the need to improve quality of care and individual outcomes while reducing cost is the holy grail. Addressing these social determinants of care is one critical way, albeit one that is challenging and still in its infancy as pilot programs around the country

demonstrate, to improve care quality and potentially combat costs.

Throughout the report, the authors describe efforts and provide an overview of the barriers and opportunities for Medicaid managed care plans and providers to address these social determinants of health.

Among the key findings and examples included in the report is the need for an integrated approach to health that brings together partners from various segments of society. In other words, managed care plans cannot do it this alone.

“When community-based providers, health plans, and state Medicaid programs all work together, it appears that is the ideal approach and model for addressing social need issues,” said Jennifer E. Moore, PhD, RN, founding executive director, Institute for Medicaid Innovation, Washington, DC, and one coauthor of the report.

Integrated Care: Screening to Identify Social Needs

Gerard A. Vitti, president & CEO, Healthcare Financial Inc of Quincy, MA, a firm specializing in enrolling the uninsured into health programs, also emphasized the need for coordinated care among plans, providers, and organizations. “The only way to attack the social patterns of health are to get folks integrated,” he said, adding that along with comingling services this also means integrating interventions.

Mr Vitti, who works with health plans to help them identify people, primarily those who are disabled or near disabled, who need interventions, emphasized that a key component of this integration is the need for a way to measure a specific individual’s needs. “I’d like to see a uniform assessment tool that can be used across the continuum, whether you are a health care provider, community organization, or health plan, so folks are on the same page,” he said.

That said, Mr Vitti emphasized that most people he sees have multiple social needs that require multiple interventions. Identifying and addressing multiple needs is difficult under the current system in which delivery of care is too siloed. “If you’re trying to help someone with transportation, you may help them with that but not their other needs,” he said, adding that desegregating services and interventions would help to manage these multiple needs.

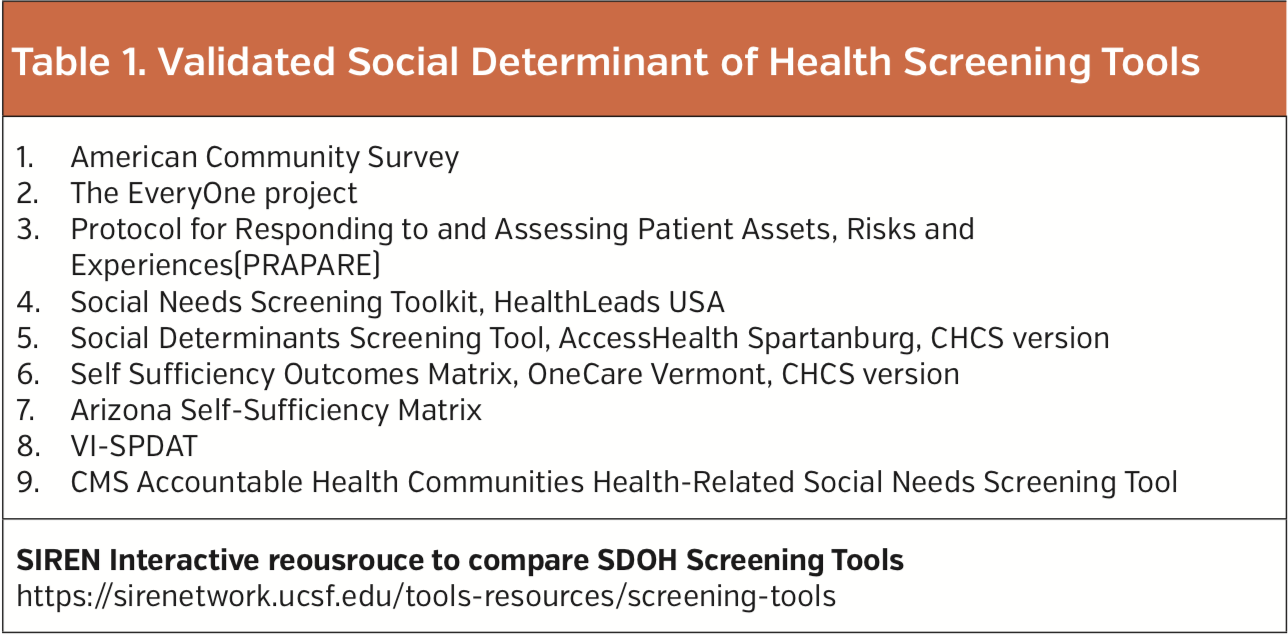

Although a single screening tool does not exist across the continuum, the Institute for Medicaid Innovation report offers what Dr Moore calls a “comprehensive list” of validated screening tools used in the United States (Table 1). Dr Moore pointed out that the Social Intervention Research & Evaluation Network (Siren) developed interactive social health screening tools that plans and providers can use to compare the different screening tools to see which best fits their situation.

Barriers and Opportunities: Funding and Standardized Metric Key

Dr Moore emphasized that the report framed barriers to addressing social needs in the context of opportunities. “Where there is a barrier, if you want to be part of the solution, you also have to talk about opportunities,” she said.

Among the barriers/opportunities described in the report are two key areas highlighted by Dr Moore—the need for a standardized metric and funding. The lack of a shared standardized measure to benchmark where progress stands and how to further improve is an opportunity to establish a nationally standardized training tool and quality metrics, she said.

Mr Vitti agreed and emphasized the need for a standardized metric especially in terms of

reimbursement. “You need to demonstrate hard metrics and hard savings in order to make the case that reimbursement should be increased to the provider, work training programs, or any intervention,” he said.

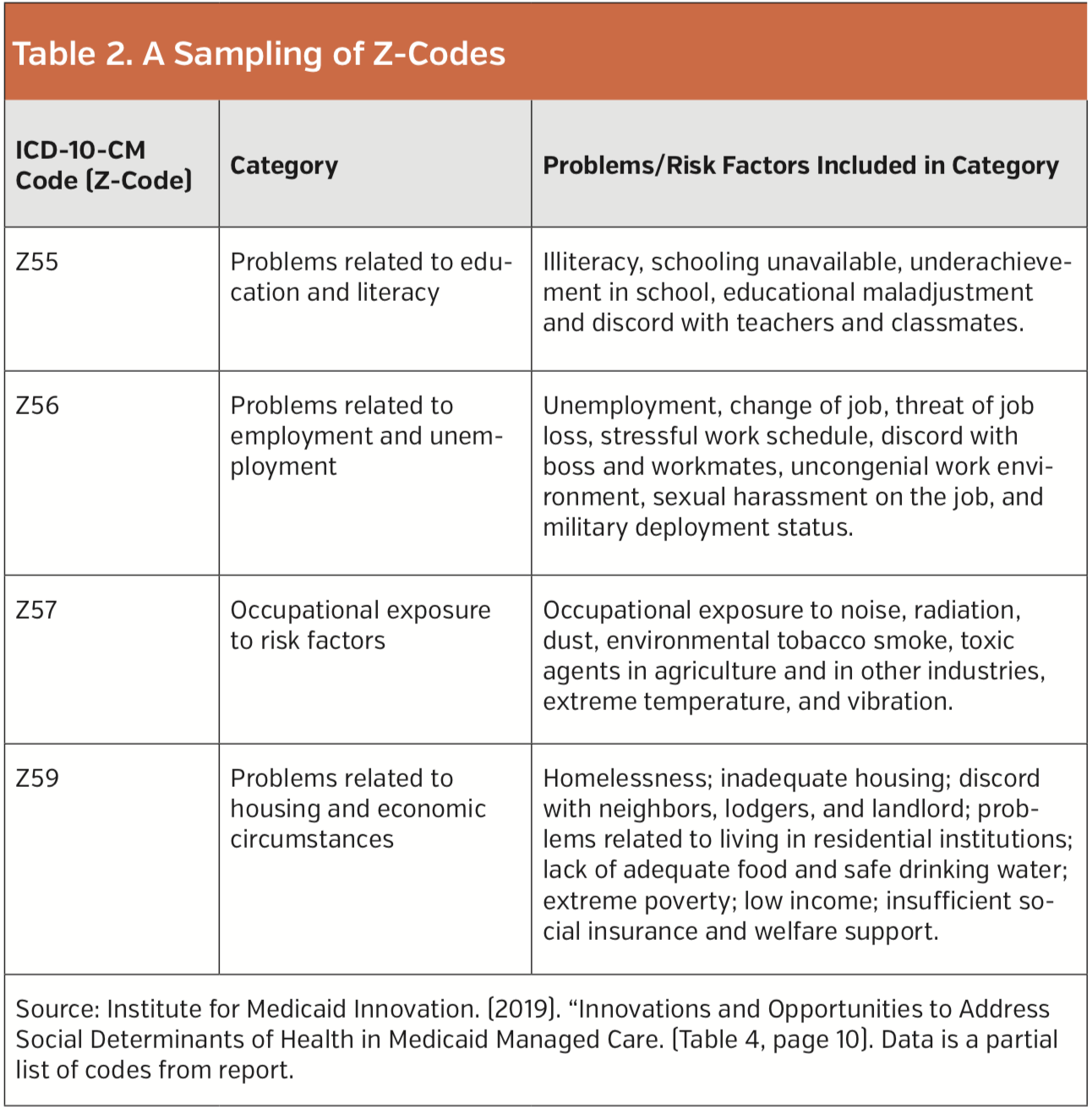

As to reimbursement, Dr Moore emphasized the clinical challenge posed by the lack

of coding for social needs. However, she discovered in her research the existence of codes (Z-codes) that could be a good starting point for reimbursement (Table 2).

In terms of funding, Dr Moore emphasized the need to figure out who funds social needs programs, pointing to the insufficiency over the long term of current funding sources for pilot programs that rely on small, local grants to support the coordination and management of social needs. “Having a way to pay for this, invest in it, and knowing who pays for it becomes really critical in a lot of areas,” she said.

Friso van Reesema, Vice President of Payer Strategy, CipherHealth, New York, NY, who works with health plans and hospitals to identify social needs of their patient populations also underscored the huge barrier of funding for nonclinical interventions. He said that many health plans and health systems have been able to exercise 1115 waivers to run smaller pilot programs to pay for these social determinants of health.

However, Mr van Reesema thinks that as these small pilot programs begin to show value health plans, health care systems, and potentially pharmaceutical companies should “get around the table to pony up the money” as they will be reap the monetary benefits of the reduced cost linked to addressing social needs.

Stable Housing: Example of Improved Health and Cost Outcomes

Five-year longitudinal data on one of the initial pilot programs to address social determinants of health shows the significant cost savings and improved health that can be achieved when going beyond addressing only the medical needs of patients.

Data from a program at the UPMC Health Plan to provide stable housing show a net-medical savings per person on average from reducing unnecessary health care. Specifically, the program that initially enrolled 25 people on Medicaid saw an average net savings for UPMC of $6384 per member per year, with an average medical costs savings of $8472 and increase in pharmacy costs by an average of $2088.

John Lovelace, president, Government Programs, UPMC Health Plan, Pittsburgh, PA, highlighted that 85% of the people enrolled in the program stayed in the program, which led to reduced use of emergency rooms, crisis services, detoxes, and hospital admissions for issues related to their disabilities or chronic health conditions. Instead, these patients relied on scheduled visits to doctors and adhered to their prescribed medications.

“All we see are the medical costs, we don’t see the social issues,” said Mr Lovelace. “The key success of this program is a true increase in the quality of life, the reduction in unnecessary medical costs, and providing people with appropriate ongoing medical attention.”

With the success of the program, it is now scaling up to target about 200 Medicaid members with housing instability. Unlike the initial program that partnered with federal funds from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to provide housing for people who are chronically homeless, the scaled-up model will reach beyond these federal funds by connecting and partnering with local housing authorities to access Housing Choice (formerly Section 8) vouchers.