ADVERTISEMENT

Initiating Insulin Therapy

Las Vegas—It can be challenging for both the patient and provider when diabetes treatment is escalated to include insulin. Steven Milligan, MD, FAAFP, DABFP, and Ben Taylor, PhD, PA-C, offered insight on successful incorporation of insulin into a patient’s treatment plan during a workshop at the CRS meeting.

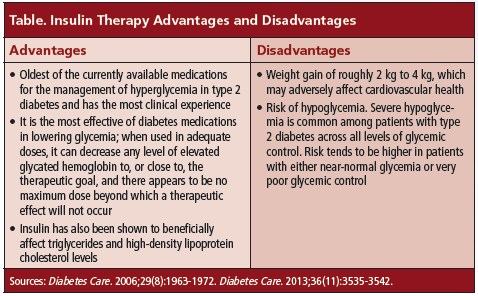

A majority of patients with diabetes are initially started on oral therapy; however, clinicians need to consider insulin therapy when oral medications are not providing therapeutic benefit. Indicators include increasing blood glucose levels, persistently elevated glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), unexpected weight loss, and polydipsia unresolved with therapy. Different formulations of short-acting and long-acting insulin are available to help patients achieve glycemic control. Drs. Milligan and Taylor reviewed the advantages and disadvantages of insulin therapy (Table).

The American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines recommend insulin if initial HbA1c is >9% or diabetes is uncontrolled despite optimal oral hypoglycemic therapy.

Drs. Milligan and Taylor reviewed the approach to starting insulin therapy based on individual blood glucose profiles as outlined in a study [Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(2):125-134]. For patients with fasting hyperglycemia and daytime euglycemia, the first-line treatment is neutral protamine Hagedorn or detemir insulin at night. The second-line treatment is short-acting insulin at dinner if bedtime blood glucose is >140 mg/dL.

In 2012, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) released a joint position statement on the management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes patients [Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364-1379]. Basal/bolus therapy offers the most precise and flexible prandial coverage. However, the “actual glycemic benefits of these more advanced regimens after basal insulin are generally modest in typical patients,” according to the position statement. The speakers said individualization of therapy is key when choosing an insulin therapy, as well as a regimen that considers patient adherence to therapy.

“Optimal glucose management should start as early as possible and continue as long as possible,” said Drs. Milligan and Taylor. “While the HbA1c goal for the general population is <7%, treatment must be individualized.”

They referenced the ADA/EASD consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of insulin and summarized the main points [Diabetes Care. 2006;29(8):1963-1972]:

• When initiating insulin, start with bedtime intermediate-acting insulin, or bedtime or morning long-acting insulin

• After 2 to 3 months, if fasting blood glucose levels are in target range but HbA1c is ≥7%, check blood glucose before lunch, dinner, and bed, and, depending on the results, add a second injection

• After 2 to 3 months, if premeal blood glucose is out of range, may need to add a third injection; if HbA1c is still ≥7%, check 2-hour postprandial levels and adjust preprandial rapid-acting insulin

The workshop concluded with the speakers addressing barriers to insulin initiation, noting that barriers exist at patient, physician, and system levels. Barriers among patients are fear of needles and hypoglycemia, inconvenience and lack of portability of insulin, and adjusting dose. Physician barriers include reluctance to become involved in insulin initiation and patient and practice factors.—Eileen Koutnik-Fotopoulos