ADVERTISEMENT

Expert Roundtable: Drug Pricing

Our experts analyze pending legislation, branded drug price increase trends, the real impact of the record number of generic drug approvals, and the value of presidential executive action.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s (KFF) October 2019 Health Tracking Poll, nearly 80% of Americans say the cost of prescription drugs is unreasonable, and both Democrat and Republican voters agree that reducing the price of prescription drugs should be a top priority of Congress. With it being an election year, the hope is that progress will be made but that is not guaranteed.

As noted in the January First Report Managed Care article about surprise medical bill legislation, neither party seems eager to allow a situation where the other party can take credit. The same hesitation exists with drug price legislation, along with pressure from industry. According to KFF, “Whether it’s sharing the credit for a legislative victory with the other party, or running afoul of the powerful drugmaker lobby, neither Democrats or Republicans are sure the benefits are worth the risks.”

We turned to our panel of experts for their analysis about pending legislation, branded drug price increase trends, what the Trump Administration’s record number of generic drug approvals means for patients and payers, and whether presidential executive action is really a long-term solution. Our experts include:

- Melissa Andel, vice president of health policy, Applied Policy, Washington, DC

- Larry Hsu, MD, medical director, Hawaii Medical Service Association, Honolulu, HI

- Charles Karnack, PharmD, BCNSP, assistant professor of clinical pharmacy at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, PA

- David Marcus, director of employee benefits, National Railway Labor Conference, Washington, DC

- Gary Owens, MD, president of Gary Owens Associates, Ocean View, DE

- Edmund J Pezalla, founder and CEO of Enlightenment Bioconsult in Hartford, CT

- William Rogers, MD, chief medical officer, Applied Policy in Washington, DC.

- Arthur Shinn, PharmD, president, Managed Pharmacy Consultants, Lake Worth, FL

- Norm Smith, principle payer market research consultant, Philadelphia, PA

- Daniel Sontupe, associate partner, managing director, The Bloc Value Builders, New York, NY

- F Randy Vogenberg, PhD, RPh, principal, Institute for Integrated Healthcare, Greenville, SC

BRANDED MEDICATIONS

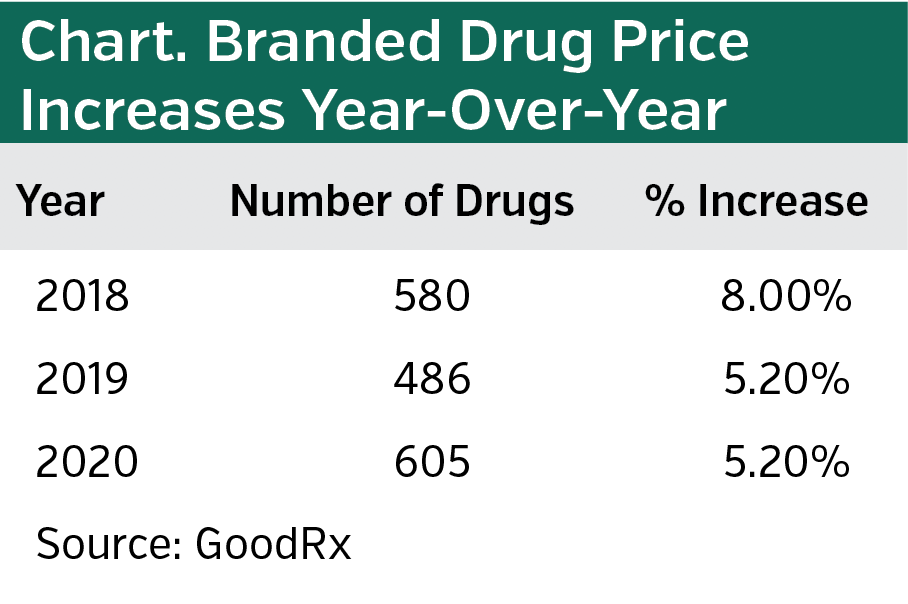

According to GoodRx, the average overall price of branded drugs continues to outpace inflation, but it is not as large a jump as 2 years ago, when the Trump Administration released its plan to address escalating prescription drug prices. The Administration may deserve some credit for the slowdown, but other factors are at play, our panelists concur. Additionally, it is noteworthy that GoodRx data shows that the raw number of branded drugs for which prices have been raised has increased after one-year decline (see chart). We asked our panelists what it all means.

Ms Andel: I do think manufacturers are more cognizant of the way that their pricing decisions may be viewed at large. Also, as the base price gets larger—either because the launch price was higher, or because a manufacturer took a larger price increase in 2017 or 2018—then a manufacturer could take a smaller percentage increase in 2019 or 2020 and still meet revenue targets. But it is difficult to draw broad conclusions because pricing decisions for single-source drugs are highly specific. How many therapeutic competitors are there? How novel is the therapy? What kind of clinical data does the manufacturer have? Where is the product in its life cycle?

Mr Smith: That’s right. There’s no question that there’s strength in governmental jawboning, and pharma is going to take the credit for it if it is given to them. But remember, these are average price increases, not individual products. Generally, as a drug gets to the end of its patent, the manufacturer raises the price. Where the drug is in its life-cycle matters. Plus, remember that we’re talking about the list price, not the actual net price for a health plan or a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM). That number doesn’t necessarily change.

Dr Karnack: The so-called public shaming process may be working, but in the end, it will always be about desire for profit, hidden behind the guise of PBMs. These increases are still outpacing inflation by a good amount.

Dr Pezalla: Public discussions have had some influence on drug price increases. Firms want to avoid being in the limelight. But as Dr Karnack mentioned, they still feel pressure from investors. In general, they are being more cautious, but I don’t see this as a self-policing trend over time.

Mr Marcus: There is some element of self-regulation. Political scrutiny and the pushback of people enrolled in high deductible health plans are certainly drivers. But notice that while the percentage increase is lower, the number of drugs affected by price increases is large. I think that’s due to the increasing number of specialty medications being dispensed.

Dr Shinn: I agree that specialty medications are the reason that the raw number of drugs experiencing price increases is going up. The result is an increasing number of necessary prior authorizations to justify appropriate utilization.

Dr Vogenberg: The industry is certainly trying to avoid regulation, but the increase in the raw number of drugs that experienced price increases shows that manufacturers are feeling the pressure to increase prices nonetheless.

Dr Owens: I think this is nothing more than random variation of price increases. If anything, seeing the growing number of drugs with price increases makes me wonder if this is an attempt to raise prices ahead of potential legislative action.

Dr Hsu: It’s difficult to tell what’s really going on without knowing the market share of the drugs with the lowest and highest increases. What if the drugs with the lowest market share had smaller increases than those of medications with high market share? Or vice versa? The impact is different depending on those factors.

Mr Sontupe: Candidly, the industry has always self-regulated. Me-too drugs and new brands that offer limited value rarely succeed, nor are they launched with premium prices. I agree that other factors need to be considered. For instance, copays. Take [heart medication] Vascepa, which is priced responsibly and extremely cost-effective, according to ICER [Institute for Clinical and Economic Review]. Yet health plans and PBMs are adding restrictions and raising copay tiers. How does this make sense? We need standards to ensure appropriate coverage of drugs.

GENERIC DRUGS

The Trump Administration is touting the record number of generic drug approvals 3 years running: 937 in 2017; 971 in 2018; and 1171 last year. But it appears that the actual impact of these approvals is not yet evident. An analysis published in JAMA in October 2019 by Jiao and colleagues concluded that while the raw number of new generic approvals is up, “the proportion of approvals for drugs that faced limited competition or had previously been in shortage remained steady.” Does this mean that pay-for-delay and other tactics, such as not sharing samples of branded drugs with generic manufacturer, are still preventing meaningful generic competition—or are other forces at play?

Dr Pezalla: It is difficult for the FDA to go much beyond prioritizing generic and other types of approvals since it cannot change the pay-for-delay tactics—that is an issue for the Federal Trade Commission.

Mr Marcus: As with branded drugs, multiple factors are at play that impact generic drug prices. Consolidation in the generic manufacturer industry presents a significant barrier. There are fewer competitors and alleged collusion. Executive action can help somewhat, but without increased competition, little will change. The industry is entrenched.

Mr Smith: The FDA has found more efficient ways to review generics and has made it a priority, but I agree other factors need to be considered. For example, as I mentioned previously, prices of branded drugs are typically raised at the end of their exclusivity period. That impacts generics, since the first generic is usually priced 80% to 85% of the brand.

Dr Shinn: Pay-for-delay tactics is certainly playing a role. It makes me wonder if the answer is to extend patents for branded drugs and eliminate pay-for-delay. That would allow manufactures to recoup more of their costs without having to engage in the practice.

Dr Hsu: For me the bottom line is that delaying the approval of effective and safe generics costs the consumers too much money.

Mr Sontupe: I do not understand why the pay-for-delay tactic is such a big deal. When the first generics are launched, the price is similar to most brands’ negotiated rate—more in some cases. Pay-for-delay simply moves money around. It does not necessarily keep costs high. I agree with Dr Shinn, brand manufacturers take on a lot of risk, and generic companies do not. I think in this case the market works just fine.

Dr Rogers: Mr Sontupe is correct that generic manufacturers are interested in selling generics that are likely to command a relatively high price, vs competing with multiple companies to sell the same generic. And, yes, sometimes the generic is priced higher than the brand. I recently saw that the generic [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug] mesalamine was priced at $752 per month and the brand was $583.

Dr Karnack: No matter what, the public perception is negative. Moves such as pay-for-delay and pricing generics higher than brands comes across as unethical. That is why the public is clamoring for legislative action.

Dr Vogenberg: I am not surprised that the increased number of generic approvals has not yet significantly impacted price. It takes time for new policies to take effect.

LEGISLATIVE ACTION

In late 2019, the House passed HR 3 that would allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices. Specifically, it would mandate price negotiations on at least 25 drugs in year one, with 50 medications added annually. It imposes strict penalties on manufacturers who refuse to negotiate. The fines start at 65% of a drug’s gross sale from the prior year and escalates each quarter until it is capped at 95%. Democrats acknowledged that the bill will not get past the GOP-controlled Senate and, thus, is largely symbolic.

Meanwhile, in the Senate, Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Ron Wyden (D-OR) proved that bipartisanship has not been booted to the curb. Their bill caps out-of-pocket costs for Medicare Part D patients and requires manufacturers to pay rebates if their price increases exceed inflation. It contains specific provisions to protect patients who enter the so-called catastrophic phase of Medicare coverage. Grassley and Wyden note that one in five Medicare patients who receive insulin reach this phase. President Trump said he is ready to sign the bill if Congress can pass it.

Mr Smith: The Senate bill has very little to do with drug pricing and more to do with benefit design.

I think it has a good chance of getting passed and signed, perhaps before the election, but definitely afterwards if President Trump is reelected.

Dr Pezalla: I tend to think it can get done this year. Both parties want to court the demographic impacted by out of-pocket Medicare costs.

Ms Andel: Yes, from a purely political sense, I think it would be really tempting to pass the Senate version heading into an election. It would be interesting to see how CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] would manage the impact on premiums that would result from capping out-of-pocket costs and shifting more financial liability to plans. Does it give plans more latitude in formulary coverage? If not, premiums will increase.

Dr Karnack: Exactly. Capping Medicare out-of-pocket costs is laudable, but who is going to pay the difference—and how?

Dr Owens: I am generally pessimistic that Congress can pass bipartisan legislation, but there is a chance this bill will pass. It’s about time the catastrophic coverage level is modified. While the impact is minimal for most inexpensive drugs, that’s not the case for a medication that costs $20,000 per month. I wonder about the inflationary provision, though, since it allows price increases up to the inflation rate on already overpriced drugs.

Dr Vogenberg: Capping out-of-pocket costs has strong consumer appeal. But I think you are going to have pushback from the industry on the inflation provision. That, along with the deeply partisan relationship Democrats have with the president may prevent passage before the election.

Mr Sontupe: The issue I have is that Medicare Part D is not set up to provide value to patients. Its goal is to reduce price, even if it hurts the patient in the long run. For example, cheap generic drugs like fenofibrates will be used in combination with a statin to prevent cardiovascular disease, even though data suggests there is no value in doing this. We increase the older populations’ pill burden without increasing the value of the pills. We need to be smarter about the coverage and what these types of bills really end up supporting as we move forward.

Mr Smith: Still, the Senate bill has a shot as passage, maybe with cooperation and compromise from House Democrats. They know that the bill they passed will never get through the Senate, but they may be able to influence the Senate bill with certain smaller provisions. Drug sample sharing, for instance. Then everyone can take credit.

Dr Pezalla: That’s right. Some version of the Senate bill could be passed and signed. It will be an actual win for an Administration that is short on real achievements.

Ms Andel: As for the House bill, now Democrats are able to say that they passed legislation that is tougher on manufacturers than the Senate version. They can take that back to their base and say they tried. It might also work as a tactic to bring manufacturers to the table to negotiate alternative policies. Now manufacturers have a concrete bill that could conceivably be enacted after the 2020 elections, depending on the outcome. So maybe that makes them more willing to agree to something less dramatic in order to avoid that risk.

Dr Owens: In my view, the House bill has no value except to increase political capital to support the Democrats position.

Mr Marcus: It establishes a template that can be used in the event Democrats are able to take control of the Senate or White House.

Mr Sontupe: I think it is largely semantics. All manufacturers have to submit pricing bids to CMS more than a year in advance in hopes of their drug being included in either a preferred or nonpreferred tier. So in reality it is already a one-sided negotiation. Go low with a price or you don’t have a chance.

Dr Vogenberg: Still, there is some value in [Veterans Administration] style contracting, but that may not align with broader consumerism trends.

Dr Hsu: I agree that allowing the largest health plan in the nation to negotiate prices would eventually drive costs down.

Dr Karnack: Allowing Medicare to negotiate would avoid single source generic monopolies. Why the VA is allowed to negotiate and not Medicare is a mystery—though perhaps not as much of a mystery as we think, given the powerful drug lobby. When you think about it, Republicans typically advocate for increased competition, but not in this case.

Ms Andel: As mentioned, the House bill can set things in play for the future, but even still, I don’t think that this policy ever gets operationalized in any significant manner. Even if Democrats gain control of the executive and legislative branches, the government does not have the capacity to negotiate prices for 250 drugs. It is more likely that they would use the authority to negotiate lower prices on a few high-profile products.

EXECUTIVE ACTION

In lieu of legislation, there is always executive action. In late 2019, the Trump Administration moved to allow drug imports from Canada. However, a look at the fine print shows that not all drugs are included. Additionally, manufacturers are pushing back, and the actual impact on consumers is a long way off because states must submit proposals for such importation. Meanwhile, Democratic presidential candidates—most notably Amy Klobuchar and Elizabeth Warren—have vowed to use the power of the pen to lower drug costs. But as President Trump has learned, the pen is only so powerful. Recall that his executive action to require drug companies to disclose drug prices in ads is now tied up in court.

Dr Karnack: Executive actions excite a party’s political base, but often are ineffective, can have unforeseen consequences, and result in lengthy litigation.

Dr Vogenberg: As the Obama Administration showed, executive action can accomplish goals, but the action’s effectiveness is largely limited to the length the president’s party holds office. It’s not an effective long-term strategy.

Mr Marcus: Since executive action is really just the first step to crafting regulations, actual near-term impact is minimal. The best a president can hope for is that meaningful regulations will follow—eventually. And that’s after the pharma lobby pushes back.

Dr Pezalla: As for drug importation, doing this on a large scale is impractical because the pharma industry can limit supplies sent to Canada or threaten Canada with higher prices by including them in a North American pricing zone, which would lump them in with the United States. We may see a few states do this in a limited way but I don’t think it will be material.

Dr Owens: Drug importation from Canada is tempting, but if it somehow moves to large scale importation, there will be availability issues for Canadian drugs. I am not sure the Canadian government supports the concept.

Mr Sontupe: We are still a free market society, as is Canada. If imports from Canada grow exponentially, US-based manufacturers will limit what they sell in Canada, making it more difficult for Canadians to get the drugs they need. Which could lead to Canada implementing non-export laws from Canada.

Ms Andel: It appears that no one from the Administration discussed this with Canada. Moreover, the rule would require manufacturers to apply for FDA approval to import a drug. But manufacturers already do this without importation, issuing a lower-cost version of products using a new NDC [new drug code] on an individual basis. It seems to have had a positive impact in limited circumstances. I suppose the question is how to scale it up.

For these and other reasons, importation from Canada doesn’t make sense to me. Canada has 10% the population of the United States, so they would have to dramatically increase their purchases in order to meet potential United States demand. And because manufacturers fulfill those sales, why would they even sell their products in higher quantities to Canadian wholesalers if wholesale importation was legalized?