Benefits of Interprofessional Collaborative Practice

As health care costs in the United States continue to climb, strategies to shift the direction of health care delivery to ensure better quality at lower cost remain front and center of the health care debate.

As formulated in the 2007 Institute of Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim framework, a way forward is to simultaneously pursue three objectives: improving the health of populations, improving the patient experience of care, and reducing the per capita cost of health care.

Recently, a fourth goal has been added to this framework: improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff. This fourth aim recognizes the rampant burnout of health care professionals and the need to improve their work life to ensure the optimal care of patients.

To achieve the triple or quadruple aim, collaborative approaches to care are gaining traction that focus on improving the quality and continuity of care to help patients better manage their health problems, particularly chronic diseases. The hope is that better management of these patients through more regular follow-up, appropriate and timely referral to specialists as needed, and keeping on top of current and new health issues will alleviate the substantial cost burden of these diseases both on the patient, as well as the health care system as a whole.

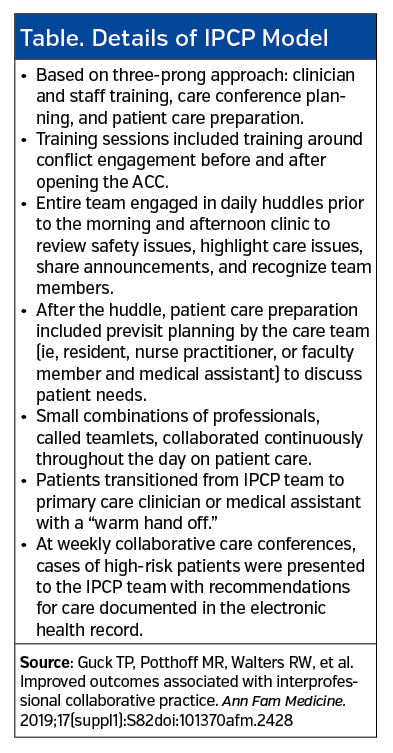

To that end, a number of models have been developed and implemented to move the health care delivery system forward based on a team approach to care vs the more traditional siloed approach to care. Among these models is the Interprofessional Collaborative Practice (IPCP) model. The World Health Organization defines the model as the following: “When multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families, [careers], and communities to deliver the highest quality of care.”

Integral to this model is a focus on training health care providers to work as a team and with patients in a collaborative setting. As such, a core feature of the model is developing and implementing competency-based interprofessional education for health care providers that focus on skills and training needed to work effectively in teams.

To date, the collaborative care aspect of IPCP has been done in settings such as operating rooms and intensive care units and in managing complex diseases. However, data is scare on its implementation in the outpatient clinic or other community sites that serve a more diverse patient population.

Recently reported results from investigators who implemented this model in a family practice clinic is one step in filling this gap. Thomas P Guck, PhD, psychologist and professor in family medicine at Creighton University, Omaha, NE, and lead investigator of the study explained that implementation of the model in an ambulatory care center (ACC) setting grew out of the desire to combine teaching with clinical care in one building.

“We intentionally built an outpatient building that has an emergency room (ER) with it for the sole purpose of applying this IPCP model,” Dr Guck said. “We designed the building to serve as a nexus between the academic world and clinical world.”

Built in 2016, the building is a family practice clinic at CHI Creighton University Medical Center-University Campus near downtown Omaha. All patients seen at the clinic are managed by the team approach characterized by the IPCP model.

In the first study of outcomes from a cohort of patients seen at the clinic, investigators found a positive association between implementation of the IPCP model and reduced cost (ie, reduction in hospitalizations and ER visits), improved patient satisfaction, and evidence of improved provider engagement.

Improved Outcomes with Collaborative Care in Family Practice Clinic

In the study, Dr Guck and colleagues assessed the effectiveness of the IPCP model in a cohort of 276 high-risk patients. Patients were deemed high risk if they met at least 1 of 3 criteria during 2016: a hemoglobin HBA1c of >9%, >3 ER visits, or readmission risk of >10 based on the LACE

score (ie, length of stay, acuity, comorbidities, ER visits.)

To assess the effectiveness of the IPCP model, the investigators compared patient outcomes and costs during the year prior to the ACC opening in 2016 and during the first year under the IPCP model in 2017 (See Table.)

The study found significant positive association between all outcomes assessed. Compared to 2016 data, patients treated in 2017 had a significant reduction in ER visits (89.7% vs 73%; P<.001), hospital visits (37.8% vs 20.1%; P <.001), reduction in A1c count (10.3% vs 9.5%; P =.001), as well as significant reductions in the total patient charges ($18,491 vs $9572; P <0.001).

“In this study, they found a decrease in ER visits by 16.7% and hospitalizations by 17.7%,” said John P Feola, MD, diplomat of the American Board of Internal Medicine, and internist on sabbatical from Georgetown University. “I think that is a phenomenal risk reduction.”

Dr Feola, whose area of expertise is preventive health care and patient education, emphasized the good team approach in the study. “I think that collaborative approach allows for the best patient care possible,” he said, underscoring the importance of communication among team members to ensure optimal care.

Sandeep Wadhwa, MD, MD, MBA, chief health office, senior vice president of market innovation, Solera Health, also emphasized the good communication among the team members in the study and particularly liked the emphasis on the team’s purposeful transfer of patients from one team member to another. “One of the things that happens when you have multiple members of the team is that it can be confusing to the patients and it sometimes can be off-putting to them,” he said. “I really liked the way the authors used ‘warm transfer’ [to describe this transfer], so the patient doesn’t feel they are being passed along.”

According to Dr Guck, the study highlights the success in training “the next generation of health professionals including family medicine residents on how to work successfully in integrated teams.” Although the study did not formally assess the impact of the model on improvements in the work life of clinicians and staff, he said that significant improvements were seen in staff engagement, satisfaction, and reduced turnover.

Challenges to Implementation

A key challenge to implementing this type of model is reimbursement, said Dr Guck. “In a fee-for-service model, collaboration and teaching are perceived as slowing [the clinician and staff] down, thereby costing money,” he explained. “In a value-based reimbursement model, the incentives are to keep a population of individuals healthy at the lowest cost; reducing hospitalizations and emergency department visits are in line with pay incentives.”

As such, he emphasized the need for value-based reimbursement models when dealing with population of patients to get the

most efficient and effective treatment and the best outcomes.

Another challenge is the cost of implementing the model. According to Dr Wadhwa, the cost of this type of model is its Achilles-heel. “Is there enough payment without a subsidy to support this model of care, particularly for people who are very complex?” he questioned.

Although the study did not include a cost analysis, Dr Guck said that a case can theoretically be made that the significant reductions in hospitalizations and ER visits seen with the collaborative approach suggest the need for fewer personnel in these areas. “These personnel are much more costly than those in an outpatient clinic,” he said.

Dr Feola put it this way. “Seeing your primary care doctor more regularly, even though there is a fee for that, is much less than a patient being admitted to the hospital for 5 to 7 days,” he said. “That empirically makes sense but I think [the authors] have to document not just percentages but the amount of money saved with this endeavor.”

To that end, he’d like to see calculations done of the potential savings in the study based on roughly the percentage of money saved by the decreased hospital admissions.

A further challenge is the difficulty, and perhaps the inability, to conduct a randomized trial to provide a more objective test of the true effect of the model on outcomes.

Without such a trial, interpreting the outcomes is less clear. Dr Wadhwa underscored the possibility that the improved outcomes in the study over the course of a year could be in part due to a regression to the mean—that is, the fact that a person who is costly one year tends to be less costly the next year.

“I think the study supports the initial hypothesis, that they are finding a positive association that merits further study,” he said, but he emphasized that a more rigorous randomized study design or concurrent comparison group IPCP is needed to get rid of any biases inherent in a nonrandomized study.

“This type of study is most useful for testing a hypothesis, but you wouldn’t want to draw a conclusion from this type of design,” Dr Wadhwha continued. “It is important now to get rid of some of the biases and still see if a positive association is found.”

While both Drs Guck and Feola agree that a randomized controlled study is the ideal type of study, they both disagreed of its utility or feasibility in this setting.

For Dr Feola, randomizing patients to a group that would receive less than optimal care (compared to the test group who would receive collaborative care with excellent follow-up) would put those patient’s in harm’s way. “I don’t think that is what is wanted,” he said.

Dr Guck focuses on the challenges of doing field work and wanting to preserve the generalizability of the findings obtained in real-life conditions vs strict control of variables that is more tailored to academic research.

“We do the best we can to get as much control as we can, but I’d also say that the other factor is generalizability,” Dr Guck said. “There is an argument going on in research for a long time on generalizability vs control.”

Dr Guck explained that it is important to see if the positive associations found at one year can be sustained over time and replicated. To that end, he and his colleagues are collecting another year of data on their high-risk cohort. They also have two more cohorts lined up to see if they can replicate their findings.

“We’re hoping with replication and sustainability that we at least answer some questions [about the effect of the model on outcomes],” he said, adding that they hope to publish the findings in the next year or two.