Payer Roundtable: The 21st Century Cures Act

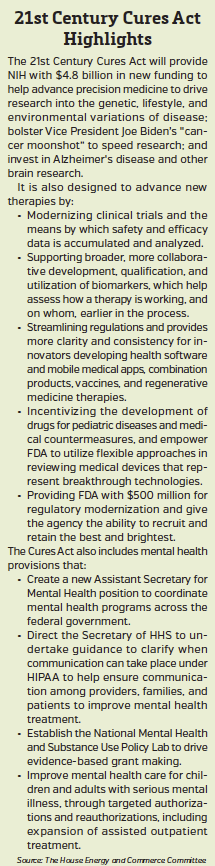

Last fall the House and Senate passed the 21st Century Cures Act, a complex set of provisions designed to increase disease research funding, alter the regulatory process for prescription drugs and medical devices, and address behavioral health issues. The bill received overwhelming bipartisan support, with only 5 senators and 26 congresspeople casting votes against it. It was President Barack Obama’s final legislative win, but also a small victory in the face of the impending repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) promised by the incoming administration.

Last fall the House and Senate passed the 21st Century Cures Act, a complex set of provisions designed to increase disease research funding, alter the regulatory process for prescription drugs and medical devices, and address behavioral health issues. The bill received overwhelming bipartisan support, with only 5 senators and 26 congresspeople casting votes against it. It was President Barack Obama’s final legislative win, but also a small victory in the face of the impending repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) promised by the incoming administration.

First Report Managed Care asked five experts to analyze the Cures Act, point out its potential value and flaws, and predict its impact on payers.

We spoke with Mitch DeKoven, MHSA, principal of health economics and outcomes research at QuintilesIMS; Karis Knight, MD, a private practice psychiatrist in Alabama; Gary Owens, MD, president of Gary Owens Associates; Michael S Sinha, MD, JD, MPH, a postdoctoral fellow in the program on regulation therapeutics and law at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School; and Norm Smith, president of Viewpoint Consulting, Inc.

What industry groups do you think benefit the most from passage of the 21st Century Cures Act?

Dr Sinha: The medical device and pharmaceutical industries pushed hard for this bill. The limited population pathway, drug development tool qualification process, and breakthrough device provisions are particularly beneficial to the industry.

Patient advocacy groups are also poised to assume bigger roles in FDA decision-making. The Act encourages greater use of patient experience data in the drug development and review process. Patient advocacy groups may be in a position to help determine how this provision is implemented.

Mr Smith: The obvious winners are the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the cancer research community as a whole, and precision medicine companies like Illumnia, which may be the leader in this field and nicely funded under the Roche umbrella. But in my opinion, the bill is poorly written, with much of the major implementation steps left to bureaucrats, along with interested lobbyists. Let’s hope they put some caps on spending, something we did not see when the ACA was implemented.

Dr Owens: Like most well-intended legislation, the act has both positive and negative aspects buried in the almost 1000 pages of legislation. While it was passed overwhelmingly in the House and Senate, I fear that approval came out of fear of not voting for increased cancer funding and opioid addiction funding, rather than actually understanding the bill that well.

Like the ACA, there are good and bad features. I agree that the obvious big winner is NIH with almost $5 billion in additional funding. Big pharma wins, too, because of provisions that will allow for faster—but not necessarily safer—approval of drugs. Medical device manufacturers also win, with the ability to get faster approval for breakthrough designated devices.

What part of the industry do you think will be negatively impacted by the law?

Dr Sinha: Well, the Act generally encourages faster approval of drugs and devices on the basis of less rigorous data, and the biggest payers for many of these expensive new drugs are government payers like Medicare and Medicaid. Limits on negotiating ability—as well as mandates for coverage of certain drugs—mean that these payers will be generally obligated to pay the high prices that these new drugs will inevitably be listed for.

The FDA can claim a modest victory with respect to retention of senior staff and hiring, but will also be under a lot of pressure to meet the many deadlines and requirements placed on it by the Act in terms of generating guidance and using the new pathways established by Congress.

Dr Owens: Unfortunately, I think the public will lose out in the end. I am concerned that safety issues will be a problem if shortcuts to marketing with incomplete data become the established norm.

Drugs may come to market faster, but likely at prices that are unsustainable. Most research and development today is targeted to rare diseases and oncology, and the track record for pricing these drugs is already established. While I don’t favor government controls on pricing, there needs to be a mechanism to return to reality. For example, Nusinersen—while admittedly for a rare disease—will cost $375k a year after a first-year cost of $750k. That price is only possible because third-party payers will be unable to refuse coverage.

I also agree that the FDA will lose out. While it will receive a half billion dollars in additional funding to cover changes mandated by the Act, it gets nothing to help correct or fund many of their other issues.

In the end, public health may be the biggest loser. The Prevention and Public Health Fund took a big cut in funding to partially fund provisions of the Cures Act. But this is where I think more money needs to be spent to improve the country’s health and welfare. More gains in longevity have come from public health initiatives than from all technology advances put together. We seem to have lost sight of the fact that most health care spending is driven more by individuals and their health care habits—or lack thereof—than it is by treatment of illness after it happens.

Is loosening regulatory barriers to speed approvals and relying on market forces enough to address drug prices? Or is more needed?

Dr Sinha: There’s nothing in the Act that addresses drug prices. The industry is not likely to reign in its own pricing. Relying on market forces is problematic since the pharmaceutical market is a highly atypical marketplace in which the users of the products (clinicians and patients) rarely know what a drug costs and there is often insufficient information to make value-based decisions.

Mr Smith: Innovation and the specialty drug companies that function like Turing [Pharmaceuticals] and Valeant [Pharmaceuticals International] are going to run into problems from Congress and from payers. I think you may see legislation limiting price increases on drugs older than their original patent life, along with public shaming, making the strategy untenable. The investment community will not put money into such companies.

However, those companies are the outliers. In general, a competitive marketplace for branded drugs is up and functioning, but none of the stakeholders—big pharma, pharmacy benefits managers (PBMs), payers, and politicians—gain anything from an open discussion about that. For some—including Sen Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and others who voted against the Cures Act—there is no price that will ever be low enough.

Dr Sinha: There is a lot that we do not understand about drug pricing, from the decision to price an item, to the PBMs and other middlemen who privately contract with pharmaceutical companies, to the insurance companies who pay the bill, to copays and coinsurance. Consumers are charged when they pick up their prescriptions, but aren’t aware of what happened before that. Also, drug costs bear no relationship to research and development costs, which would not be the case in a traditional market.

Apart from the pricing question, there seems to be good news in the Cures Act for both patients and the pharmaceutical industry. But are there potential dangers in the approach the Act takes?

Mr DeKoven: Providing patients quicker access to new technologies that save lives—at a reasonable price—is rarely a bad thing, as long as the FDA’s safety and efficacy requirements are not compromised.

Dr Owens: Consumers often have a well-intended, but misguided view of drug development. This is fueled by media reports that often hail new treatment results from early trials as breakthroughs, when in reality the findings are preliminary. I fear that Congress and the public are tilting at windmills if they think that they can accelerate good science just by throwing money at the process.

Even the standard clinical trial process is at risk for being undermined. The randomized clinical trial is the gold standard, [but] real-world evidence standards may mean that such trials will become less important for drug and device approval. While I favor generating real-world evidence in addition to trial data, there needs to be a way to find a balance point for both. The Cures Act may have tipped this balance point.

Mr Smith: Everybody wants cures, especially patients with chronic and/or life-threatening diseases. Pharma wants to rapidly move assets to market, and to have the freedom to price its products to the value it perceives during a product’s entire lifecycle. But that is in a perfect world, and we are not living there.

A lot goes on behind the scenes that most do not see, pointing to the complicated path drugs take to reach approval. Having enough drugs to supply study patients is a challenge, as is supplying medications for terminally ill patients outside of a study. It becomes all the more complicated for companies with tight funding and limited regulatory experience. Additionally, anytime a drug is used outside of a study, side effects must be reported to the FDA within 24 hours. But too often the doctors using the drug have not been vetted, as would be done when a pharma company or clinical research organization initiates a clinical trial site.

Continued on next page

The law authorizes $4.8 billion in NIH funding over 10 years. Some say it is not enough, others point out that there is no guarantee money will be appropriated. Do you think there is a valid concern—or will funding halt if spending hawks raise concerns?

Mr Smith: This is a onetime bonus as part of the Cures Act. The NIH will always say it needs more money, but over the years the level of controls and the percentage of grant denials varies. From a pharma perspective, NIH can sometimes conduct basic science research that the industry would have trouble getting funded, and study areas pharma hasn’t researched.

Dr Sinha: Increasing NIH funding is extremely important since publicly funded science has supported the development of the most transformative drugs we have today. However, even if the money is all appropriated, it is still a relatively modest overall increase of NIH funding, particularly given the fact that the NIH actually lost about 22% in real purchasing power in recent years due to budget cuts and sequestration.

How will the Cures Act impact payers, and what should they expect see to happen first?

Mr Smith: More new product approvals for cancer and rare diseases are likely to affect payers. There also may be a mild impact in how pharma will be able to promote unapproved indications. It will be interesting to see how the promotion of unapproved uses influences a plan’s prior authorization process, but that will take time and vary from payer to payer. On the research side, it will be a decade before new drugs that result from the Cures Act hit the market.

The Act may have an impact on the genetic testing industry. Medical directors are skeptical about the value of genetic tests, something our group saw 10 years ago. Precision medicine is a great idea in academia, but not so much in the hands of community doctors.

Dr Owens: I think payers will face more demands by their members for access to new treatments and new technology—perhaps prematurely. And without new ways to manage prices, costs will increase downstream to pay for the new technology that will take the place of the old.

Dr Sinha: The FDA is one major gatekeeper in the pharmaceutical marketplace; insurance companies are the other. FDA approval does not equate to access. As more expensive drugs are approved on weaker evidence, payers will exclude them from their formularies. We’re already seeing this happen with [Exondys 51 (eteplirsen; Sarepta Therapeutics)], the new Duchenne muscular dystrophy drug that was approved on the basis of a trivial increase in dystrophin production—based on one recent report, only five of the top 13 commercial health insurers plan on covering it.

Also, cost containment will become a priority. CMS must have greater freedom to make coverage determinations for a voucher system to work. We will likely see a shift in federal drug coverage policies that match those of private insurers: price negotiations, tighter formularies, and the ability to exclude expensive drugs.

Mr DeKoven: Let’s not forget that the responsibility of life science manufacturers to determine, demonstrate, and communicate the value of their technologies to health care stakeholders does not go away with the passing of this Act, and should remain a key part of any commercialization strategy.

What one behavioral health provision in the Cures Act do you hope will reach the practice level with the most potential impact?

Dr Knight: The Act clarifies that the federal Medicaid statute permits same-day billing for mental health and primary care services. I hope this will be interpreted as allowing patients to see a psychiatrist as well as a psychologist, or other therapist/caseworker, the same day that they receive care from their family/internal medicine or specialty clinician if needed. Measures that facilitate coordination of care are crucial because they keep especially fragile patients from falling through the cracks. Patients, especially in rural areas, should be allowed to see me and their OB-GYN, family practitioner, and their therapist on the same day.

Is there anything else that you think will help advance the practice of behavioral health?

Dr Knight: Creating a chief medical officer (CMO) position within SAMSHA [Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration] will make a huge impact on ensuring quality care. Such an appointment signals the importance of including those with the most training, continued training, and the most experience—including the most experience working with other stakeholders. Psychiatrists often serve as mediators in hospitals between clinicians from different specialties, as well as between clinicians and patients, and are well versed in this role.

What concerns you about implementation of the behavioral health initiatives outlined in the Cures Act?

Dr Knight: The problem is, mental health parity has been legislated before, so I am not convinced that things will be different this time around. Perhaps we need to find a phrase other than “mental health” to be clear that we are talking about serious medical problems that impact the brain, which is part of the body. Separating mental and physical health is an outdated construct that leads to minimizing these problems and perpetuating stigma.

It isn’t that complicated, Parity means parity. Guidelines have been written and re-written. Until the right stakeholders are made to do this, they won’t. Regulation and enforcement are needed.

What value do you see in the provision that allows small businesses to reimburse their workers for health care costs?

Dr Sinha: I see the potential for this provision to shift employees from Medicaid to the private insurance market in states where Medicaid expansion occurred, and to help provide additional coverage to uninsured persons in non-Medicaid expansion states that may not have been able to obtain coverage otherwise. Since it goes into effect immediately, it may further complicate ACA repeal efforts while providing a temporary guarantee of coverage for affected employees, depending on how the new administration proceeds.

Do you see value in the provision that ensures funds will not be taken away from hospitals whose demographics might penalize them?

Dr Sinha: Having trained at two hospitals where demographics and social forces often played a role in readmissions, I’m very sensitive to the need to ensure that hospital quality is assessed fairly and hospitals are not penalized for factors beyond their control as they work to deliver high-quality care to patients.

Dr Owens: We are in an era where other market forces will continue to drive quality of care and outcomes, so this [provision] will have a minimal impact on reducing quality.