ADVERTISEMENT

The Impact of New Medicaid Work Requirements

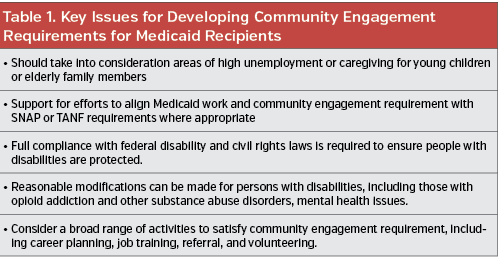

On January 11, 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced its new policy guidance for states that wish to apply for a waiver to make Medicaid eligibility contingent on work or community engagement. Stated as a way to help Medicaid beneficiaries improve their well-being and achieve self-sufficiency, CMS invoked Section 1115 of the Social Security Act that allows them to approve demonstration projects that promote the objectives of the Medicaid program. CMS has composed a number of key issues for states to consider when developing proposals (Table 1).

The waiver is directed primarily at nonelderly adults without supplemental security income (SSI) (either parents or childless), most of whom became eligible for Medicaid in states that chose to expand coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This population comprises a minority of individuals under Medicaid. The majority of Medicaid beneficiaries will remain exempt from the work/community engagement requirement under the waiver. These populations include seniors, disabled or medical frail persons, those in drug treatment, students, those experiencing a catastrophic event, those providing caregiving services, and those receiving unemployment compensation. However, the exemption for some of these populations may only be temporary.

Of the eight states that have applied for the waiver, Kentucky is the first and only state to date who has been granted the waiver and is proceeding to implement it in its state. The states with proposals under review are Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wisconsin.

For proponents of the waiver, it provides a way for states to be flexible in how they administer their Medicaid program with the aim to improve health outcomes of beneficiaries while finding ways to more efficiently administer the program with an eye to decreasing administrative costs.

“States are looking for flexibility and partnership with the administration to test a variety of reforms, and this [the waiver] is one of those new flexibilities,” said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, adding that there is no consensus among State Medicaid Directors as to whether or not the work requirements are the right approach to Medicaid.

Saying that the response by states ranges from those that have been eager for something like this for a long time to those that want no part of it, Mr Salo emphasized that State Medicaid Directors are fine with the waiver as is as long as it remains optional and not mandated.

“This is going to be complex and will require a lot of thinking about how to make this actually work,” said Mr Salo.

This complexity in making it work is one of the chief complaints by those opposed to the waiver.

“We are creating a significant amount of administration red tape and barriers for everyone to jump through,” Emily Beauregard, MPH, director of Kentucky Voices for Health, a nonpartisan coalition that advocates for the health of Kentuckians, who emphasized the extra burden this will place on Medicaid recipients who already face significant challenges just to function in their daily lives.

Within this opposition to the waiver is the real fear that people who rely on and need Medicaid will fall through the cracks. Providers too are worried, according to Ms Beauregard, because of the uncertainty of how these changes will affect the services they provide.

“Community health centers will see someone whether or not they have health insurance,” Ms Beauregard said. “If they have an increase in uninsured patients or if coverage for patients is turned on and off and they have no longer have retroactive eligibility, which helps to pay the bills, then clinics will be eating that cost and will have a harder time knowing how much revenue will be coming in. This affects the type and volume of services they can provide.”

However one looks at this, it is clear that states who are granted the waiver will be challenged to ensure that only the appropriate individuals are targeted for complying with the work and community engagement requirement. This population of nonelderly adults without SSI comprises only a small proportion of Medicaid recipients, estimated at about 25 million. Of these, 60% are already working and 79% live in families with at least one worker (64% with a full-time worker and 14% with a part-time worker).

The infrastructure and processes that will need to be developed to administer such a program to capture these individuals is considerable. Following is a look at what Kentucky has proposed and how they are going about developing and implementing such an infrastructure.

The Kentucky Waiver

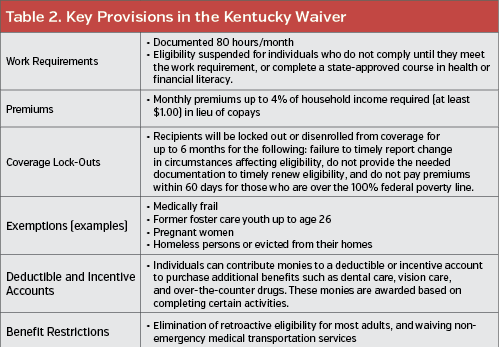

The demonstration waiver granted to Kentucky includes modifying the state’s existing Medicaid expansion by creating a program called Kentucky Health in which the new work/community engagement requirement will be applied to the current Medicaid expansion population as well as other adults covered by Medicaid. The waiver includes a number of key provisions (see Table 2).

Ms Beauregard highlighted that these provisions are targeted at about only 2%, or fewer than 10,000 people, in the entire Medicaid program in Kentucky. Despite this, she cited the much larger Medicaid population that will have to jump through the same hoops to demonstrate they are exempt.

“When you look at the different components of Kentucky Health, you see barriers everywhere, at least through the eyes of a policymaker, a provider, or anyone who works with the Medicaid population,” she said.

One main barrier, she said, is the paperwork and documentation needed to establish either being exempt from the work/community engagement requirement or to certify that the work/community engagement requirement is being met.

“Whether you are eligible or not, whether you are meeting the requirements or not, it will be harder to get enrolled, harder to stay enrolled, and more people will fall through the cracks,” Ms Beauregard added.

Mr Salo also highlighted the challenges overall to developing an infrastructure that will require new systems and processes to track individuals as they move through the system.

“How are states going to build the infrastructure in such a way that people don’t fall through the cracks,” he asked.

For providers, the fall out of people falling through the cracks and no longer eligible for Medicaid coverage could have a big impact on the services they can provide and revenues to keep community clinics viable. Citing the expansion of services and revenue following Medicaid expansion in Kentucky that led to the opening of clinics and addition of providers and staff, Ms Beauregard underscored that providers now are in a wait and see mode.

“Everyone is cautious about hiring, expanding any services, and even thinking about cutting services,” She said.

Looking at this from a different angle, Mr Salo suggested that the waiver offered may actually prod some states that were reluctant to expand Medicaid to do so given the modifications to the program that the wavier permits, and therefore actually increase the numbers of people covered by Medicaid.

“It’s also important to look at this in a larger context,” he said. “Is this [waiver] integral to maintaining or increasing coverage?”

One issue that will need to be addressed is whether making Medicaid eligibility contingent on work or community engagement stays within the legal parameters of the objectives of Medicaid. A lawsuit filed on behalf of 15 Medicaid recipients in Kentucky is making the claim that it does not.

For articles by First Report Managed Care, click here

To view the First Report Managed Care print issue, click here