How Do Direct-to-Consumer Ads Impact Payers?

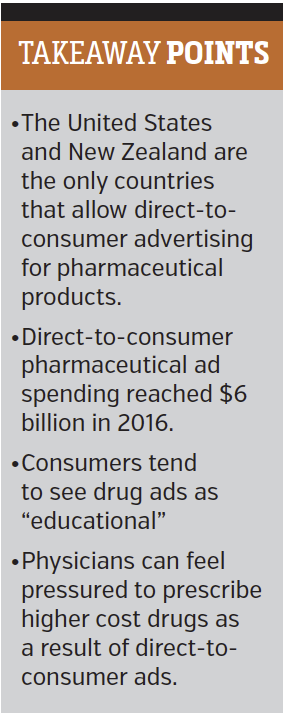

Consider, for a moment, the global stage of direct-to-consumer advertising for prescription drugs, where the United States stands with New Zealand as one of only two developed nations on the planet that allow it.

Consider, for a moment, the global stage of direct-to-consumer advertising for prescription drugs, where the United States stands with New Zealand as one of only two developed nations on the planet that allow it.

The practice became more common in the United States after the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued new rules in 1985, but most advertising still came in print form at the time because of a requirement to disclose a summary of the warnings, precautions, and adverse events of a drug—a tall order for a radio or TV commercial.

However, that all changed about 20 years ago when the FDA eased up on regulations and issued a new set of guidelines allowing commercials to include only the most common adverse effects under the condition that they pointed viewers to additional sources of information that describe the complete risks.

Fast forward to today, when viewers tuning into a sitcom, sporting event, or nightly news program are highly likely to see an ad for a drug. In the last 4 years, pharmaceutical advertising has grown more than any other leading category.

Spending topped $6 billion last year, with television taking up a hefty slice of that pie, according to a Kaiser Health News report that cites data from Kantar Media, a consulting firm that tracks multimedia advertising. The top three ads based on total spending in 2016 were fibromyalgia drug Lyrica ($313 million), rheumatoid arthritis drug Humira ($303 million), and heart arrhythmia treatment Eliquis ($186 million).

How Ad Spending Ties into Cost

This proliferation of direct-to-consumer advertising is controversial in a climate where rising drug costs have been increasingly called into question. The heavy ad spending inevitably raises a drug’s retail price to recoup the cost of promotion, and the net result is a higher fee for consumers.

But the cost of this advertising is not the main issue, Steven Woloshin, MD, MS, professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice told First Report Managed Care. The issue is that it gets people interested in newer, more expensive drugs.

The goal, of course, is to get patients or their family members to remember a specific drug and ask for it by name, which steers patients away from generics and less expensive alternatives. “There’s literature showing that advertising does increase patient interest in drugs,” he said, “and that when patients talk to their doctors about it, then they are more likely to prescribe them.”

The American Medical Association (AMA) echoed these sentiments in a June statement, saying, “Pharmaceutical companies know their advertising pays off by having patients pressure physicians to prescribe certain medications that cost more than lower-cost alternatives and are not necessarily as efficacious.”

The organization called on the industry to be more transparent about the price tags on drug products, arguing that patients would benefit from an ability to compare costs. It isn’t the first time that AMA has taken aim at the way prescription medications are advertised to consumers. In 2015, the organization called for an outright ban.

Debate Laid Out

Ad advocates point out that this form of communication provides the public with a greater awareness of treatments and encourages patients to have better discussions with their physicians. It can also help remove the stigma associated with medical conditions like male erectile dysfunction or depression, the pharmaceutical industry argues, allowing potentially reluctant individuals to step forward and seek treatment.

Opponents, meanwhile, contend that direct-to-consumer drug ads misinform patients by idealizing the benefits and glossing over the dangers and drawbacks. The ads also potentially medicalize normal conditions like wrinkles or low testosterone, lead to the overuse of prescription drugs, and promote medications before the long-term safety effects are fully known and understood.

Beyond that, physicians have voiced concerns that drug ads can waste valuable appointment time as physicians are forced to explain why a specific drug may not be the most appropriate option. It is time that could be devoted to focusing on the discussion of appropriate treatment options, tests, or lifestyle adjustments.

Efforts to Better Inform

In our culture, we tend to think of direct-to-consumer advertising as education, explained Chien-Wen Tseng, MD, MPH, University of Hawaii John A Burns School of Medicine associate professor and associate research director of family medicine and community health. But there is something unsettling about the general public being “educated” by those who stand to profit the most from the purchase of their product.

“In most products or services, we can compare and shop around to see which is the best in the market for us in terms of quality, effectiveness, cost, and value,” she added. “How can we do that for a prescription medication?” Because advertising does not provide all the answers, patients rely on their doctors, but this, too, can be problematic considering pharmaceutical companies spend billions advertising to physicians and other prescribers.

To some extent, the FDA has attempted to be the impartial voice that informs patients and physicians of the true benefits and risks of any given drug, Dr Woloshin explained. For example, its online Drug Trials Snapshots feature information about the benefits and harms of many new drugs. “That’s kind of an obscure website,” he said, “but it’s a good start.”

For years, he has nudged the agency to provide understandable data-based drug information to doctors and their patients that would encourage more informed decisions. Together with Lisa Schwartz, MD, MS, (also a professor of medicine at Dartmouth), he developed a method of conveying the evidence used by the FDA to decide whether a drug should be approved.

While the FDA’s Risk Advisory Committee voted to adopt the production of these “drug facts boxes” that use a simple table format to share key details, the agency eventually noted a lack of human resources needed to move forward with the project. So the husband-wife team founded Informulary Inc to take on the task.

Regulatory Outlook

Although President Trump has declared intentions to reduce the cost of prescription drugs, there has also been a push to reduce regulation and regulatory barriers for drug approvals, essentially creating pathways that would allow drugs to be approved more quickly and hit the market faster. This would likely increase the volume of pharmaceutical advertising in both the direct-to-consumer and direct-to-provider spaces.

“In that climate of trying to remove regulation it’s hard to imagine that there’s going to be much appetite in Washington for increasing the regulation of drug ads or eliminating drug ads,” Dr Woloshin predicted. “I don’t think that’s likely to happen.”

Furthermore, previous efforts to prohibit direct-to-consumer ads over the past two decades have fallen short, typically on free-speech arguments made by the powerful drug lobby and claims that ads offer useful treatment option information to patients.

Even if direct-to-consumer drug ads were banned, it’s just one part of a much bigger promotional machine. There is a whole set of activities the industry uses to influence how people think about what it means to be sick, what it means to be well, and what symptoms should trigger visits to the doctor.

There’s a huge underlying cultural phenomenon underway, according to Dr Woloshin, and direct-to-consumer advertising is only one small piece of the puzzle.