ADVERTISEMENT

Drug Prices: Could Taxing Sharp Increases Impact Costs?

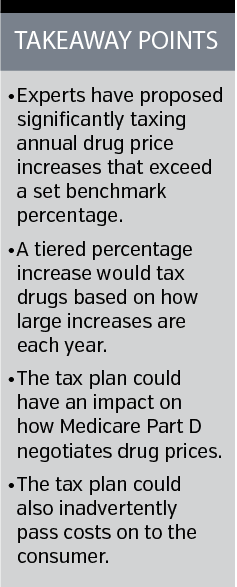

Hard-hitting tax penalties can be added to the list of ideas put forth for reining in rising drug prices. On March 29, 2017, senior Democrats introduced legislation called the Improving Access to Affordable Prescription Drugs Act that looks to lower costs and increase transparency. While the Act includes a variety of measures, section 202 targets companies engaging in so-called price gouging with a tax provision.

Hard-hitting tax penalties can be added to the list of ideas put forth for reining in rising drug prices. On March 29, 2017, senior Democrats introduced legislation called the Improving Access to Affordable Prescription Drugs Act that looks to lower costs and increase transparency. While the Act includes a variety of measures, section 202 targets companies engaging in so-called price gouging with a tax provision.

Modeled after rebates already in place for Medicaid, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Department of Defense, this would establish a tax on drugs with price increases that exceed the inflation rate. The amount of the penalty would depend upon the scope of the price increase.

Revenues stemming from an annual price increase above the rate of inflation but below 15% would be taxed at 50%. The tax rate would be 75% for an increase between 15% and 20% and would bump up to 100% for an increase greater than 20%.

Section 202 would also penalize cumulative price increases over a period that is the least of: the five most recently completed calendar years, all years the drug was sold in commerce, or any calendar years after March 29, 2017.

“This is a good start to bring some changes in pricing practices, particularly by bad players— those who try to rely on gaining revenue through price increases rather than innovation,” Jeah Jung, PhD, MPH, associate professor of Health Policy and Administration at Penn State University, told First Report Managed Care.

Medicare Part D Implications

To examine the potential impact of the proposed tax, Harvard Medical School researchers Thomas Hwang and Aaron Kesselheim, MD, JD, MPH, analyzed Medicare Part D prescription drug spending. In 2015, a total of 1805 drugs (that made up 68% or $92.8 billion of gross Part D spending) had annual price increases above the inflation rate, and 638 of them had increases that topped 20%. Furthermore, between 2011 and 2015, there were 1088 drugs with cumulative price increases above 50% and 481 drugs above 100%.

If the proposed annual and cumulative price spike taxes were applied to Medicare Part D sales in 2015 alone, it would amount to approximately $9 billion and $26 billion, respectively.

If enacted, this tax “could fundamentally alter the dynamics of pharmaceutical pricing in the United States and result in initial tax receipts of up to tens of billions of dollars annually,” the coauthors speculated in a Health Affairs blog post dated May 12.

A shake-up of this magnitude could result in some unintended consequences, however. Joshua Cohen, PhD, research associate professor at the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD) told First Report Managed Care that the fallout could apply to Medicare Part D in ways that resemble the results of the best price provisions of the Medicaid drug rebate program—a law that requires brand-name drug manufacturers to provide Medicaid with the lowest price offered in the rest of the marketplace.

Before its enactment in 1990, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), hospital systems, and other purchasers had been able to negotiate deep discounts. Following the law’s passage, however, drug manufacturers terminated discount contracts to the commercial market rather than extending these deep cost cuts to Medicaid.

Drug companies were no longer inclined to offer smaller purchasers discounts and incentives that would also apply to a nationwide entity like Medicaid, which made up a much larger portion of the total market than any single HMO or hospital system. Dr Cohen added that this issue could be further heightened considering how large Medicare is, even in relation to Medicaid.

Story continues on page 2

Impact on Patients and PBMs

While the actual (net) price paid by insurers for a drug is typically lower than the sticker price because of rebates and other discounts, this gap between the list and net prices can spread in a hurry and the roughly 28 million uninsured may have to pay that steeper fee.

Increases in list prices also impact the insured under the current system. Since coinsurance and deductibles are based on the list price of pharmaceuticals, a bigger price tag could result in higher patient out-of-pocket costs even if the net price has not changed.

By lessening rebate amounts and reducing the gap between the list and net prices, Dr Jung explained that the proposed tax could help lower list prices and indirectly help patients’ pocketbooks. While it is not known exactly how rebates are used, the general sense is that some percentage flows to the middleman, she added, so if rebate amounts are reduced the revenue of pharmacy benefit managers could wind up taking a hit as a result.

Value Frameworks Needed

The aim of the proposed tax increases—to discourage rapid growth in drug prices, which could thereby slow rising out-of-pocket prescription drug costs in the future—is well-intended, Dr Cohen noted. Recent price increases have been criticized for not being based on value, so there appears to be a disconnect between price and value in certain instances.

But in some scenarios, there could be justifiable reasons behind a price hike. Clinical studies could provide new evidence that a drug is more effective or safer than initially believed, for example, or a drug might receive approval for a new or expanded use.

The dilemma here, according to Dr Cohen, is determining who ought to decide whether price and value align.

“We have a number of fledgling value frameworks that may provide evidence needed to either support or refute justification of a price increase,” he explained. But there are only so many drugs they can analyze, and the methodologies used by value frameworks such as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) have been criticized, especially in regards to the assumptions underpinning the models.

Will the Tax Be Implemented?

There have been several companies that have already announced pricing policies that fall in line with the proposed tax. AbbVie and Novo Nordisk pledged to limit branded drug price hikes to single digits annually, Mr Hwang and Dr Kesselheim pointed out that the CEO of Allergan called for a goal of reducing price increases to the rate of inflation. The threat of a tax might just provide the added nudge needed to reach an agreement that limits drug price increases.

One existing model that has found success is the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme in the United Kingdom, a voluntary arrangement between the UK Department of Health and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. First introduced in 1957 and periodically renegotiated, participating companies agree to cap price growth for brand-name drugs for the following 5 years.

“To date, reform of pharmaceutical prices—balancing the value provided by new medicines with the burden of escalating costs on patients and payers—has been stymied by resistance from parties benefiting from the complex status quo,” Mr Hwang and Dr Kesselheim wrote in their commentary. “The tax proposal, among other provisions in the Improving Access to Affordable Prescription Drugs Act, could help move real change forward.”

But will this tax concept go on to become a reality? From Dr Cohen’s vantage point, it is not a likely scenario.

“While there is some bipartisan support, I’m skeptical it will be sufficient to allow for implementation of such taxes,” he noted. “The pharmaceutical lobby is powerful, and has influence among both Republicans and Democrats. Moreover, reallocative taxes are not especially popular in today’s political climate.”