ADVERTISEMENT

Challenges in Pain Management: Looking to The Future of Pain Management Therapy

Like the aphorism “the road to hell is paved with good intentions,” well-intended efforts to better manage pain over the past couple of decades by the increased and more liberal use of pain analgesics, namely opioids such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, and methadone, has led many patients to a darker spot than where they started. The number of people dying of inadvertent overdose of prescribed opioids, or from heroin as a cheaper alternative to prescribed opioids, is now the topic of daily news.

Numbers cited by the CDC tell the story: the amount of prescription opioids sold in the United States and deaths from prescription opioids have both quadrupled since 1999, more than half a million people have died from drug overdoses between 2000 and 2015, and every day 91 Americans die from an opioid overdose.

When looking at more recent data, the CDC estimates that opioids were involved in just over 33,000 deaths in 2015 with people in the Northeast and South Census Regions of the United States having the most significant increases in fatalities from drug overdose.

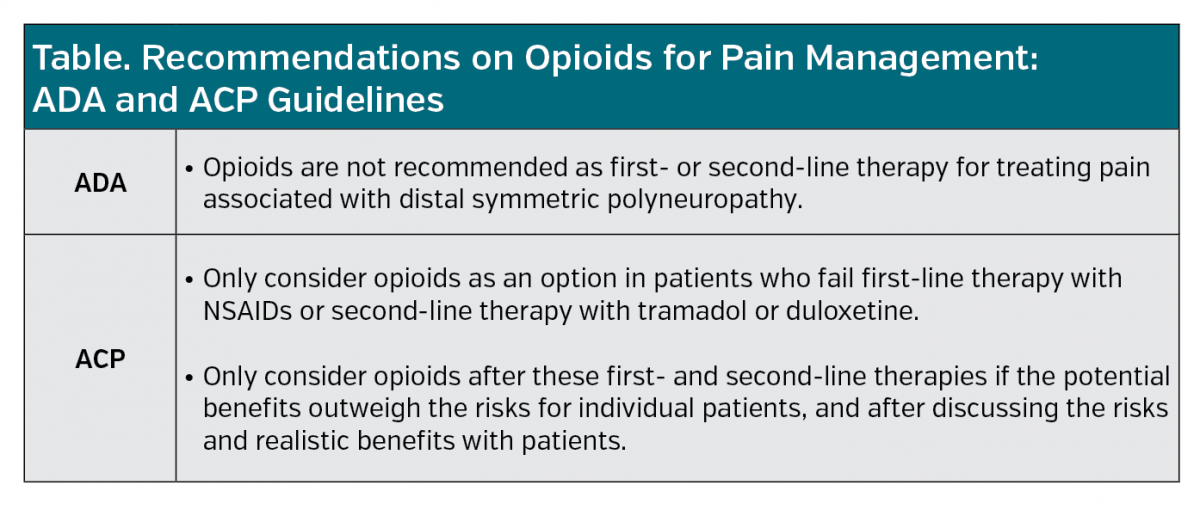

Given the grave and expanding concerns over misuse and abuse of opioids and the increase in fatal overdoses, management of pain is undergoing a swift sea change. In 2013, the American Academy of Pain Medicine issued a statement prioritizing the importance of proper pain management to provide some guidance on the appropriate use of opioids. More recently in 2017, both the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) published guidelines on pain management that recommend significantly limitations on the use of opioids (Table).

This trend has payers wondering what does this shift away from the use of opioids for pain management indicate for managed care?

Impact of Guidelines on Prescribing Opioids

While explaining that the recently published ACP and ADA guidelines are having a definite effect on the willingness of physicians to prescribe opioids, Edward Michna, MD, board member of the American Pain Society, and an anesthesiologist and pain specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Chestnut Hill, MA, cautioned that it is a chilling effect.

“I think the quality of care will suffer,” he said. “It will limit a lot of options for patients that probably deserve to have opioids as a therapy.”

Part of the chilling effect is the paperwork that physicians now are required to complete to prescribe opioids, such as the constant need for prior authorization.

In addition, Dr Michna said the guidelines are now being used by insurance companies and managed care beyond the intended populations and prescribers.

“[The guidelines] were supposed to apply to only primary care populations, but they are now being universalized by insurance companies and applied to physicians who are not in primary care but who are specialists and to patient populations for whom were not the intended populations,” he explained.

Barbara LePetri, MD, SVP director of medical and scientific services at The Bloc, a Health Wellness Communications Company, also suggested that the guidelines may result in reduced quality of care in some patients.

“While prescribing opioids has its share of issues, such as addiction and profound constipation, for those in pain, they are an effective treatment,” she said, adding that they may be the only option for medically managing pain in patients who either can’t take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSIADs), such as patients with gastrointestinal ulcers or cardiovascular disease, or for whom NSAIDs do not provide adequate pain relief, such as in patients with extensive osteoarthritis. Other patients that may fall into this category include patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy who can’t take a nerve-specific agent such as pregabalin because of drug interactions.

More Education of Pain Management Needed

Both Drs Michna and LePetri agreed that what is needed is more education and understanding of proper pain management.

For example, saying that the ACP had the right motivation behind its recommendations, Dr LePetri said that the group should have given more thought to the implementation of the guideline.

Along with strongly discouraging the use of prescription opioid painkillers to treat back pain, even for chronic back pain, the ACP guideline recommends alternative therapies such as exercise, acupuncture, massage therapy, meditation, and yoga before trying medical treatments such as anti-inflammatories or muscle relaxants based on the current literature. “The ACP concludes that these alternative therapies can work as well as or better than drugs and without side effects,” Dr LePetri said.

She added that the roll out of the guidelines should have been accompanied by “extensive medical education for physicians, and a thorough assessment by payers regarding what they will and will not cover.”

This statement highlights a crucial problem with the guidelines—many alternative therapies are not covered by insurance plans. “This makes it difficult for patients, particularly elderly patients, to access these therapies,” Dr LePetri said.

Dr Michna agreed. Saying he thinks opioids became the easiest choice of therapy for physicians to prescribe for pain management in part because insurance covered them, he emphasized that alternative therapies are largely not covered. “Insurance companies don’t want to pay for injections, physical therapy, psychiatric evaluation, and care, or referral to a multidisciplinary pain clinic,” he said. “What is incentivized is what is done.”

Now that the pressure is on eliminating or restricting the use of opioids instead of incentivizing physicians to prescribe them, providers are needing some education on what the

options are, who will cover them, and what the unintended consequences may be to eliminating opioids altogether.

Holistic Approach to Pain Management

For Daniel Sontupe, managing director at The Bloc, and a First Report Managed Care Advisory Board member, the shift away from opioids to treat pain needs to focus on a holistic approach to pain management. “The organizations that embrace this shift will drive value for their members and themselves,” he said.

Although he said this shift away from opioids may have a negative impact on short-term outcomes in pain management, he suggests the importance for managed care providers to keep their eye on the more substantial goal of long-term outcomes.

“The goal for health plans is to impact the triple aim [of health care delivery], “he said. “If we can build a program to eliminate the use of opioids, the long-term impact to population health outcomes will greatly improve, while net costs will decrease.”

Within this shift away from opioids and a greater focus on alternative therapies for managing pain, Mr Sontupe sees a shift toward prevention and an evolution of case managers to health coaches to ensure the regular use of preventive tools like exercise, massage therapy, and yoga.

“Additionally, health plans that embrace these new treatment options will become more attractive options to employers and employees, and provide an opportunity for new growth,” he said.

For Dr. Michna, the key for proper pain management is a rational approach to care that is based on individualized care. Saying that the public health crisis of opioid abuse has thrown out rationality and balance on how to manage pain, he cautioned that simply eliminating opioids could have secondary unintended consequences. “If you deny opioids to someone in pain and do not offer alternative effective therapies, then that might push them to seek medications on the street,” he said.

As such, he emphasized a more judicious approach to pain management that begins with understanding the medical and psychological health of each patient to properly determine which patients may be good candidates for opioids and which ones may be better suited for alternative therapies.

What is strikingly evident is that if insurance companies, government agencies, medical associations, and providers want to eliminate or drastically reduce the use of opioids as a component to pain management, coverage of alternative therapies is warranted and has come due.