Challenges in Pain Management - Struggling to Treat Pain and Prevent Addiction

As opioid addiction has rapidly developed into a nationwide crisis, payers and providers have been left fighting a battle on two fronts: effectively treating pain and consciously fighting addiction. While states have a public health obligation, payers have members with legitimate pain issues. First Report Managed Care asked a panel of managed care professionals how payers should handle treating pain adequately and appropriately, while minimizing the potential for addiction and misuse.

As opioid addiction has rapidly developed into a nationwide crisis, payers and providers have been left fighting a battle on two fronts: effectively treating pain and consciously fighting addiction. While states have a public health obligation, payers have members with legitimate pain issues. First Report Managed Care asked a panel of managed care professionals how payers should handle treating pain adequately and appropriately, while minimizing the potential for addiction and misuse.

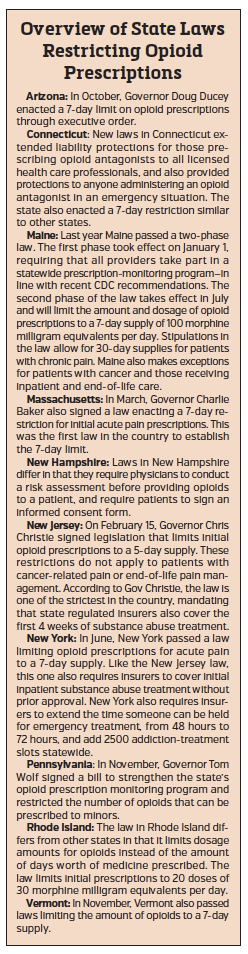

Furthermore, in response to recent public pressure against opioid misuse, and the perception of overprescribing, an increasing number of state legislatures are taking matters into their own hands, introducing laws aimed at limiting prescribing. Our panel addressed the implications of such limits and shed light on how payers and other industry stakeholders are responding to these new laws.

We spoke with Jennifer Christian, MD, president of Webility Corp; Roger Crystal, MD, CEO of Opiant Pharmaceuticals; Charles Karnack, PharmD, assistant professor of clinical pharmacy at Duquesne University; Norm Smith, president of Viewpoint Consulting, Inc; and Barney Spivack, MD, national medical director Medicare case and condition management at OptumHealth.

Where do you think the tipping point is between good public health policy and putting excessive limits on clinical autonomy?

Dr Crystal: It depends on who has developed the state regulations. If they’ve been written by experts in the field, then that is far more encouraging than if written by politicians. In the case of the latter, they are unlikely to be in the interest of patients.

Mr Smith: State regulations should limit the non-medical use of scheduled products. If a member has a chronic condition and is using opioids, this should be monitored by the prior authorization process of the plan. If higher doses are necessary, then the prior authorization process should work. State regulations that over-reach may not only limit a provider’s ability to treat members, they might also limit a health plan’s reimbursement for legitimate medical expenses covered in the member’s coverage agreement.

Dr Spivack: If state regulations decrease the effective management of pain or prevent access to effective strategies, they will be counterproductive. The state has a duty and a public interest to help ensure that dangerous use of opiates is restricted. But they should not stop there. States need to ensure access to effective drug treatment programs. And they need to track metrics, such as rates of opioid overdose, to make sure the regulations are having the desired effect.

Dr Karnack: State regulations do not work if the approach is “one size fits all.” Having nonclinicians come up with dosing numbers and durations of therapy is not the answer. Legislatures should not practice medicine.

Dr Christian: If the argument is that complying with the state regulations is too onerous, well, there are plenty of other administrative things that clinicians have to do in their workflow. This is just another one of those things. And since it involves an issue where there are high death rates, it seems worthwhile. In defense of clinicians, it is incumbent upon states to create monitoring programs with a good user interface. There is no excuse for having to deal with something that is unwieldy.

Some believe the pendulum has swung too far, liming prescribing at the expense of adequate pain relief. Do you agree?

Dr Christian: It would be interesting to find out who is complaining about it. I agree that you have to respect the need for physicians to be efficient and to not have to jump through unnecessary hoops every time they write a prescription. On the other hand, you have to protect the patient and use the public policy tools to improve public health.

I’d like to know how the physicians who are complaining practice and what type of patients they are treating. Many patients have been led to believe that opioids are the right treatment, and they are going to complain vociferously if you take them away.

Dr Spivack: Limits won’t be seen as overly-restrictive if: (1) there is sufficient latitude to allow for exceptions; (2) following the regulations don't involve excessive time, documentation, or interference with usual workflow; and (3) the rules are consistent with the best medical evidence for effectiveness.

Mr Smith: The vast majority of Americans have a prescription benefit that requires online adjudication. It should not be all that hard to spot the providers who are overprescribing. Now, if the pharmacy is taking cash for these drugs, that should be stopped, under threat of being kicked out of the retail network. The systems are there without excessive state regulations—if we have the will to stop opioid abuse.

As states draft and enact laws to limit opioid prescribing, to what extent do you believe clinicians should be restricted?

Dr Spivack: There is little reason to prescribe opiates for an acute problem for longer than a week, and this is what many state prescribing guidelines attempt to enforce, with exceptions as needed. Because physician education and guidance has not generally been sufficient, it does help to have some regulatory restrictions, as long as these are sensible and consistent with clinical practice.

Mr Smith: Clinicians should be monitored by both the payers and likely by the individual states. If a member is using opioids for nonmedical reasons, they may be “doctor shopping.” If they are paying cash for the prescription, the state should be responsible for stopping them. I’m confident most payers’ quantity limits would not adjudicate another opioid prescription. As always, exceptions should be allowed through a form of prior authorization.

Dr Karnack: Clinicians could be restricted based on specialty. For example, restrict emergency physicians but not oncologists. There can also be limits by duration of therapy—for instance, acute pain, not palliative care. Prescribing restrictions are already in place in many states for podiatrists, dentists, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. But history shows us they often do not work, as they are open to interpretation.

Dr Spivack: Agreed. It's not clear that there are fewer physicians who actively prescribe opiates than previously as a result of prescribing limits. Nor is there increased recognition of opiate overuse, abuse, and related morbidity and mortality. The use of nonpharmacologic pain management has been underemphasized in practice and clinically effective strategies—largely involving cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, and lifestyle interventions—should be more accessible.

Dr Christian: States have a duty to respond appropriately to clear threats to the public’s health, especially when the private sector has shown it is not doing so on its own. The question is, how far should states go? In my opinion, most states’ prescription monitoring programs are remarkably nonintrusive. Their goal is to ensure that clinicians are making adequately informed decisions when they prescribe opioids, especially in the setting of chronic nonmalignant pain. And who can argue with that?

Dr Crystal: In isolation, restricting the ability of clinicians to prescribe opioids is controversial because it could deny patients with genuine pain access to appropriate treatment. A more appropriate approach is clinician education that focuses on pain control in general. For example, some pain is a “good phenomenon”—as it represents healing. Knowing the cause of pain allows clinicians to assign the appropriate treatment.

Opioids are often the easy way out because, while they are very effective, they are only for short-term pain relief. Chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis benefit from increasing muscle mass and physical therapy. It delivers long-term gains, but requires a lot of patient compliance.

When opioids are deemed appropriate, it is important to educate clinicians to provide rescue medication alongside every prescription. There are almost 9 million people in the United States taking opioids long-term—30 days or longer. They are at higher risk of overdose, and would benefit from co-prescribing.

How can payers help to reduce the amount of pain management drugs that are misused?

Mr Smith: The majority of payers take a hands-off position on limiting drugs to reduce pain, as long as it is within the benefit design. Years ago, payers told us it was not their role to monitor potentially abusing members. I think those days are long gone. Every medical professional has a responsibility to stop the nonmedical

use of opioids. From what we’ve seen, payers have accepted that responsibility.

Dr Spivack: Some payers now have pharmacy fill restrictions based on milligram morphine equivalents over a 30-day period for those with noncancer nonpalliative pain, as well as on the use of extended release opiates. Some opiates are now off formulary.

So-called “lock-in programs”—where patients can only receive payment for the opiates if they use certain prescribers and pharmacies—have been used in Medicaid. The CARE [Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery] Act has a provision establishing lock-in programs for Medicare Part D plans in 2019. Anthem has a lock-in program in place in 14 states.

Still, lock-in programs are not foolproof; as there is evidence of increased use of out-of-pocket payment for opiates associated them.

Dr Christian: Workers’ compensation has an even bigger problem with opioids than group health payers do. Some states have put drug formularies in place, and many payers have developed pharmaceutical utilization review programs. When clinicians know that writing a prescription for more than 7 days is not going to be approved, they tend to stop writing them.

In an era of increased focus on care coordination, are payers and clinicians working together closely enough to make sure chronic pain is adequately treated, while at the same time spotting potential abusers?

Dr Christian: The issue I have with some payers is their hypocrisy. They talk piously about what they are doing to save lives by aggressively limiting opioids, but fail to increase access to other evidence-based treatments for chronic pain. I want to know what they are doing to help the clinician whose patient is in pain? What other treatment interventions are payers encouraging physicians to make use of instead? Are the payers going to authorize more physical therapy, more patient education in self-care, more instruction in yoga or meditation, or more cognitive behavioral psychotherapy by psychologists trained in pain treatment? That is what we should be seeing.

Dr Spivack: As of March 2017, Aetna no longer requires that clinicians seek approval before prescribing drugs used to ease withdrawal symptoms.

Dr Karnack: Guidelines can help redirect clinicians to alternative therapies. Also, care coordinators, often nurses, are great resources on logistics, coverage, and safety.

Mr Smith: Interoperable electronic medical records certainly could play a role, as can guidelines. However, I believe the payer prior authorization process is the most potent weapon. If a provider is part of the “abuse” system, guidelines mean little. Beyond that, more potent but less “abuseable” drugs—such as nerve growth factors, may help. Earlier physician education is also needed.

Dr. Christian: It’s strange to me that most of the effort at discouraging over-reliance on opioids has focused on doctors. Why haven’t we been telling patients that opioids are not particularly effective for chronic pain. Most patient education efforts are directed at risks and benefits of the drugs. Patients who believe that opioids are the only or best or most powerful choice for treating pain are probably going to simply accept the risks.

With that in mind, a few years ago, a group of clinicians and I wrote a patient education document that starts out by saying opioids are not the best treatment for chronic pain and describes some of the more effective alternatives. It is starting to get some traction, has been adopted by Kaiser Permanente in Northern California, the state of Tennessee’s health department, and the state of Ohio’s Bureau of Workers’ Compensation.

When you say “starting to get some traction,” why do you think it takes time?

Dr Christian: I think we are now in the second half of the opioid enthusiasm-rejection cycle. About every 20 or 30 years, we forget past lessons, rediscover opioids, and decide they are a great option for pain. They are enthusiastically embraced by doctors and patients alike. Over time, it gradually becomes clear that opioids are actually a mixed blessing. Ultimately the prevailing sentiment becomes, “Oh dear, we have created a lot more harm than good here!” This is followed by a very strong pendulum swing against almost any opioid prescribing at all. Decades later, the cycle starts again. In public health school, I was taught that opioid use and addiction have followed a cyclical epidemic pattern since the late 19th century.

The way I see it the tide is turning against opioids again, but we just can’t fully tell yet.