Biosimilar Buzz: Cancer Drug Knock-offs Promise Greater Access to Medications

The fight against the second most common cancer in the world just received a notable boost. According to new research, a drug undergoing development by Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc, called Myl-1201O, has proven to be clinically equivalent to Roche Holding AG’s Herceptin (trastuzumab), a breast cancer medicine used to treat patients whose tumors generate a protein called HER-2.

The fight against the second most common cancer in the world just received a notable boost. According to new research, a drug undergoing development by Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc, called Myl-1201O, has proven to be clinically equivalent to Roche Holding AG’s Herceptin (trastuzumab), a breast cancer medicine used to treat patients whose tumors generate a protein called HER-2.

Hope Rugo, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco and lead author of the report, presented the findings of the clinical trial at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting in June. The study involved 500 patients with metastatic disease who were treated with chemotherapy for 24 weeks along with either Herceptin or the Mylan drug. At 24 weeks, the overall response rate was 69.6% for patients on the Mylan drug and 64% for those on Herceptin, and the rates of serious side effects were comparable as well.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

RELATED CONTENT

Courts: Biosimilars Must Give Brand-Name Drug Makers Advanced Notice

Tesaro's Ovarian Cancer Drug Study Succeeds, Shares Soar

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“This is indeed an important milestone,” Dr Rugo noted. “Due to the cost of the medication, it is not available to many women worldwide who could benefit from treatment, or it is available with limited exposure durations. Having alternative therapies with similar efficacy and safety will improve access to this life-saving treatment.”

The findings supporting the equivalence of Myl-1201O have only added to a wave of excitement surrounding biosimilars—the term given to biotechnology drugs designed to be similar to reference biologics in terms of safety, purity, potency, and efficacy. Because biologics are among the highest-cost drug treatments on the market today, biosimilars offer big potential for lower-cost alternatives. The potential for savings is due to the fact that biosimilar sponsors have not taken on the burden of cost associated with innovation and full clinical trials, and they can take advantage of the reference biologics’ existing data as well.

Homefront Progress

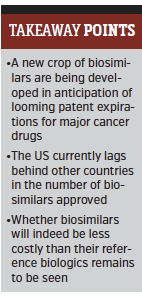

Mylan is developing the drug along with Biocon Ltd, a biopharmaceutical company based in India, where the medicine is already on the market. There, the medication is one of several approved biosimilars. To date, 20 biosimilars have been approved for marketing in Europe by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and many have been approved in Japan, Australia, and Canada as well. By contrast, only two biosimilars have been approved for use in the United States by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Although the United States has lagged behind the rest of the world in terms of providing a clear pathway for biosimilars, two crucial developments have driven the push forward, according to a report released last year by Mark Ginestro, a principal in KPMG’s strategy practice focusing on health care and life sciences.

The first was the Biosimilar Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), incorporated into the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, which allows for biosimilar development. The act was a component of the ACA’s objective to reduce costs in the US health care system.

This has facilitated the FDA approvals that have already occurred and are expected to come in the months and years ahead. So far, two biosimilar drugs have been approved by the FDA. The first was Novartis AG’s Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz), a medication for the treatment of side effects of chemotherapy that is biosimilar to Amgen Inc’s Neupogen (filgrastim), that was approved in March 2015. The second was Inflectra (infliximab-dyyb; Celltrion, Inc), a biosimilar to Janssen Biotech, Inc’s Remicade (infliximab), which was approved in April 2016 for multiple indications.

The other big factor that has pushed biosimilars forward in the US revolves around impending patent expirations. “We will see in the 2018 timeframe… some of these big cancer drugs going off patent,” Ginestro said, “and then you’ll see those biosimilars coming on the market as well.”

Those big cancer drugs include trastuzumab as well as Amgen’s Neulasta (pegfilgrastim), Roche’s Avastin (bevacizumab) and Roche and Biogen Inc’s Rituxan (rituximab). Several companies, including Pfizer and Amgen, are already developing biosimilar versions of these drugs with the hopes of bringing them to market in the years ahead.

Another major development in the biosimilars space is the number of collaborations that have emerged between pharmaceutical companies. Companies are increasingly collaborating to develop biosimilars in order to mitigate the risks involved, Ginestro said. These risks are owing to the large investment required relative to that for generic pharmaceuticals, the newness of the technology, and the uncertainty regarding the approval pathways and reimbursement pathways for these drugs.

Product Protection

Whereas traditional pharmaceuticals are inorganic, small-molecule compounds created through chemical processes, biologics are proteins and antibodies derived from genetically modified living sources such as bacteria, yeast, or mammalian cells. Because the cell lines in a source are unique and drug products are created through complex biological systems and production methods, biopharmaceuticals made by companies other than the original innovator are not identical copies.

“The interesting thing about these biologics is that they’re much more complicated organisms and entities,” Ginestro explained, “and so they often have many patents.” And this can lead to battles over intellectual property. He pointed to the current legal dispute between Amgen Inc and Sandoz Inc, in which Amgen has accused Sandoz of infringing on its patent for Neulasta by applying to license its pegfilgrastim product, as one example of what can stem from this complex patent space.

The push to build a wall around products, so to speak, is one of several responses by manufacturers of the original brands as they work to minimize the impact on their sales. Beyond developing stronger intellectual property rights and pursuing patent litigation in order to postpone the progress of the competing products, differentiating the product itself is yet another strategic maneuver.

Continued on next page

A case in point is Amgen’s Neulasta On-body Injector. “Traditionally you have to go to a doctor’s office or cancer therapy center to be infused with this drug,” said Ginestro, “but they’ve developed a drug development technology that will allow you to self-administer at home. That’s a way for them to create a stickier product in the marketplace.”

Another tactic is to increase the medication price prior to patent expiration in anticipation of competing drugs on the way, and then to discount the price once these competitors are actually on the market.

Overseas Expertise

While biosimilars and their original counterparts duke it out in the US, it remains to be seen just how much cost savings will actually trickle down to insurers and patients. If looking to the one and only currently on the US market for a clue, Ginestro said that Zarxio is being sold at a 15% discount. “I think a lot of people were expecting that it would be discounted more than that,” he noted, “but the fact that they’re the only other player, I think Sandoz feels like it is in a position where it can gain a share without a heavy discount.”

For more in the way of examples and lessons learned, many are turning to Europe, where biosimilars were first introduced a decade ago. Overseas, there is a large price discount on filgrastim, both on the reference product Neupogen and on the multiple biosimilars on the market, Ginestro said, which has led to significant savings. And, generally speaking, the more versions there are of any one drug on the market, the steeper the discounts.

It’s a dynamic that can impact drug utilization. Although, ideally, patients with cancer would always be able to receive the drugs that they need, when biosimilars came on the market and prices dropped, utilization actually went up in some cases. The conclusion is that there were cancer patients that either weren’t getting their drugs or weren’t getting enough. “Cost is a market access barrier,” Ginestro said. “At some point in the chain, somebody was making a decision based on price about how much or how often and whether to prescribe.”

While Europe has shown that biosimilar launches are not like generic or branded launches—and that product uptake can vary widely based on the dynamics of the individual medication, the market, and the competitive landscape—it is clear that the United States is a whole other ballgame. These factors also help to explain why it has taken so long for biosimilars to actually hit the market.

In some countries in which there is a single-payer system, the government is the one customer. As a result, these governments are very motivated to reduce costs and will do what is needed to push legislation through and clear up any uncertainties in litigation disputes. According to Ginestro, the United States has “a much more fragmented and complex regulatory environment and a much more complex political environment and reimbursement environment.” As such, the path to biosimilar adoption has taken longer to get through the US Congress, the FDA, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

The Big Unknown

One of the main differences between generic pharma and biosimilars is that interchangeability has not yet been established for biosimilars. Initially, the ones that have already been approved and will likely be approved in the United States are not interchangeable, and the view is that they won’t be, Ginestro said.

In cases where interchangeability is allowed, the prescribing pharmacist can automatically substitute a biosimilar drug for the biologic indicated on the provider’s subscription without a doctor’s approval. Many payers and biosimilar manufacturers are pushing to establish clarity on what is needed to get to this point.

“That’s a big unknown,” he said, “and that’s a big market-determining factor.”

Encouraging and promoting clarity around interchangeability is probably the biggest aspect payers should be focusing on moving forward, Ginestro added, along with encouraging education among the provider force about the benefits of biosimilar products.