ADVERTISEMENT

Abuse-Deterrent Opioids: High Costs and Vague Outcomes Hurt Uptake

Not a day goes by without news, often headlined, of the damage rendered to individuals, families, and communities by the opioid abuse crisis sweeping the United States. The scope of the problem is both broad and deep, indiscriminate in who it touches, yet seemingly affecting specific communities, such as rural underserved areas, with more devastation than in others.

Not a day goes by without news, often headlined, of the damage rendered to individuals, families, and communities by the opioid abuse crisis sweeping the United States. The scope of the problem is both broad and deep, indiscriminate in who it touches, yet seemingly affecting specific communities, such as rural underserved areas, with more devastation than in others.

Getting a handle on the many moving parts of the crisis is turning into a herculean effort to tame a beast in heat—one requiring creating good policy and laws to encourage and mandate changes to current manufacturing, distribution, and prescribing practices, but equally one requiring a harder look at pain itself and the desperate need for all stakeholders to recognize and support better ways to manage pain over the long haul.

In his incoming address as the new US Food and Drug Administrator (FDA) commissioner, Scott Gottlieb emphasized the priority his organization will give to the continual and growing opioid abuse crisis calling opioid abuse “our greatest immediate challenge” and “a public health crisis of staggering human and economic proportion.”

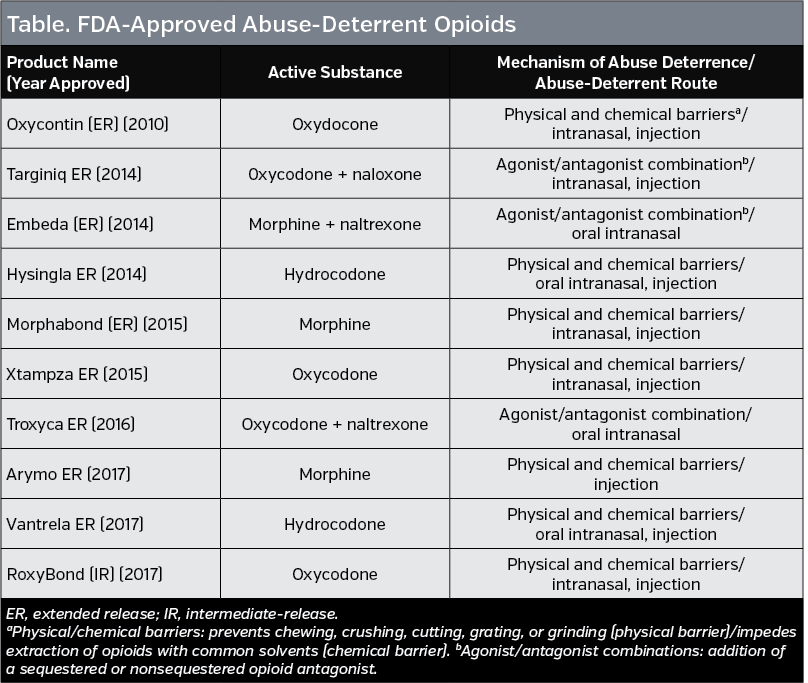

One key area in meeting this challenge is the focus by the FDA on encouraging pharmaceutical companies to develop abuse-deterrent opioids. In 2013, the FDA published a guidance for industry on evaluating and labeling formulations of opioids that meet standards of abuse deterrence. To date, there are 10 abuse-deterrent opioid formulations with an FDA label (ADFs) available that meet FDA approval for labeling as abuse-deterrent (Table).

What remains to be seen is whether these new formulations do in fact curb abuse and addiction. The FDA has mandated postmarketing epidemiologic studies for ADFs to determine whether the formulations actually reduce the misuse and abuse of these opioids. As of yet, few data are available that show these agents actually do what they are intended to do. Recently, however, a formulation without FDA-approved labeling (extended-release oxymorphone hydrochloride) was reported to be associated with a serious outbreak of HIV and hepatitis C as well as thrombotic microangiopathy in some patients who injected the drug despite efforts to curb its abuse by gel coating the drug to prevent crushing or snorting it. The FDA has requested the manufacturer of the drug to take it off the market.

What is known is that these new formulations are expensive. Whether their expense can offset the still unknown benefit is a big question mark made bold by a recent draft evidence report published by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) that gave the cost-effectiveness of these drugs a C+ rating.

Given the high cost of these drugs, the FDA is currently working on guidance to help encourage the production of generic abuse-deterrent products. Whether this effort will provide the necessary financial incentive to use these drugs is still unclear.

Story continues on page 2

High Cost, Low Usage

“These are very expensive formulations and we don’t have any evidence of direct patient effects,” Edward Michna, MD, board member of the American Pain Society, and an anesthesiologist and pain specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said, summing up what appears to be the main concern with the currently available abuse-deterrent opioids.

That these drugs are expensive is not questioned. In the recent report by ICER, a nonprofit organization that evaluates the effectiveness and costs of medical tests and treatments, the average annual cost of an ADF prescription (90 mg morphine equivalent dose) was estimated at $4234 compared to $2124 for a non-ADF prescription. The draft report also found that it would cost patients and insurers $645 million over 5 years if all opioid medications were made with ADFs.

The report concluded that “without stronger real-world evidence that ADFs reduced the risk of abuse and addiction among newly prescribed patients, our judgement is that the evidence can only demonstrate a ‘comparable or better’ net health benefit.”

Given the high cost of ADFs, Jeffrey Bratberg, PharmD, BCPS, clinical professor, College of Pharmacy, The University of Rhode Island, emphasized their limited use. One reason, he said, is that most of the currently available (9 of 10) ADFs are extended-release formulations and make up less than 10% of all opioids prescribed in the United States. He said that the one available immediate-release ADF may have an impact on cost given the much larger market for immediate-release opioids.

However, he emphasized the elephant in the room—the continuing lack of data on the efficacy of ADFs to do what they are intended to do. “The problems remain in the lack of data n impact on reducing total misuse and nonmedical use of prescription and illicit opioids,” he said. “In the end, these are more expensive drugs with no data on greater efficacy and questionably greater safety.”

Need For more Efficacy Data

What the current status of these drugs reveals is the need for additional data to determine if indeed they do and can deter abuse. To this end, the FDA just announced it will hold a 2-day public meeting July 10 and 11 to better understand whether these drugs are making a real-world difference in terms of decreasing the pattern and frequency of abuse.

Advocating for wide use of ADFs given their safety potential, Charles Argoff, MD, president, American Academy of Pain Medicine Foundation, and professor of neurology at the Albany Medical College, and director of the Comprehensive Pain Center at Albany Medical Center in New York, emphasized that the current higher cost of ADFs compared to non-ADF opioids sets up a vicious cycle of nonprescribing that in turn disallows sufficient assessment of their efficacy because of the low numbers of patients using them. Weighing the real-world cost-effectiveness of ADFs, therefore, remains inadequate.

“Payers and pharmaceutical companies need to harmonize their approach to this so that more people have easier access to these agents so that we can see their true impact and change the direction in their development if the current direction isn’t helping to achieve our outcome of effective prescribing with more safe outcomes,” he said.

One issue raised by Dr Argoff is whether pharmaceutical companies should consider charging less for these ADFs until and unless they can be proven to do what the FDA is trying to facilitate—reduce abuse.

“Just because you have FDA approval, you shouldn’t expect that the new product is worth the higher cost,” he said. “The logic here is that none of the companies that have these ADF formulations approved had to prove in their clinical trials that they were changing abuse behavior in a large enough patient population to address their true impact on opioid abuse and misuse.”

One way the FDA may be approaching this is by encouraging the developing of ADF generics.

“Encouraging access to generic forms of these products is an important step toward balancing the need to reduce opioid abuse with ensuring access to appropriate pain treatment for patients with pain,” an FDA spokesperson told First Report Managed Care. “Physicians may be reluctant to prescribe opioids with abuse-deterrent properties, in part, due to their higher cost. Given the lower cost, on average, of generic products, the availability of generic products with abuse-deterrent properties has the potential to improve access to these products for appropriately selected and monitored patients.”

The FDA is currently working on a guidance to help potential sponsors of genetic versions of abuse-deterrent solid oral opioid drugs, and will be providing updates on when to expect the final report.

Opioids Only Part of the Answer

“Pain management is not synonymous with opioid prescribing,” Dr Argoff said. He stressed that pain management remains a maturing field in which opioids only play a part.

“We all know there are better ways of approaching the pain problem in general instead of throwing medications or opioids at patients,” Dr Michna added, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach that includes psychological services, physical therapies, and alternative therapies, as well as medical intervention.

One area needing attention is a better understanding by both physicians and patients of the goal of pain management, which, he said, is to minimize pain while increasing function. It is not, he emphasized, total pain relief in many cases.

“There are lots of areas that need to be improved in terms of physician and patient education, which includes informing them of these other therapies to counter the reaction that there is nothing else to do but give patients opioids,” he said.

But like the cost of ADFs, a more holistic approach to pain management, even with proven effective and safer outcomes, is expensive. “This approach is very expensive,” said Dr Michna. “Insurance companies disallow alternative techniques or therapies and they incentivize providers to do something cheaper, which may include taking a handful of opioids.”