Management of 2-Stage Breast Reconstruction in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: A Case Report

© 2023 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) refers to a group of heritable connective tissue disorders (HCTDs). Clinical hallmarks of EDS include tissue fragility, joint hypermobility, and skin hyperextensibility. One of the consequences of tissue fragility is abnormal wound healing and scar formation, posing potential challenges for surgeons treating these patients. There are limited previous reports of EDS patients undergoing mastectomy and/or breast reconstruction, and none wherein the patient had diagnoses of both vascular EDS (vEDS) and classical EDS (cEDS).

Case. A 41-year-old female was referred to the plastic surgery clinic for breast reconstruction consultation after diagnosis of left breast lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). She has a past medical history of cEDS and vEDS with associated pectus carinatum, thoracic root dilation, and hypermobile joints. After shared decision making with the patient and her breast surgeon, it was decided the patient would benefit from bilateral prophylactic mastectomies with immediate 2-stage tissue expander (TE) reconstruction.

Results. The patient reported here had an unremarkable postoperative course. Her complications were limited to more than average bleeding during the first stage of reconstruction, which was easily managed with meticulous intraoperative hemostasis, and a small uncomplicated submuscular seroma 1week postoperative. She had no complications following TE to implant exchange and continues to heal well.

Conclusions. This case report documents a case in which a patient with both cEDS and vEDS had an unremarkable surgical and postoperative course following bilateral prophylactic mastectomies with 2-stage TE reconstruction.

Introduction

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) refers to a group of heritable connective tissue disorders (HCTDs) that includes 13 various subtypes.1 While there is considerable genetic and phenotypic variability among the types, the underlying cause of all EDS types is a defect in collagen structure or biosynthesis. Most commonly, type V collagen genes COL5A1 and COL5A2 are affected.2

Clinical hallmarks of EDS include tissue fragility, joint hypermobility, and skin hyperextensibility.3 One of the consequences of tissue fragility is abnormal wound healing and scar formation, posing potential challenges for surgeons treating these patients.4 Certain unique pathologies associated with the various subtypes of EDS can cause further issues during surgery, with vascular (vEDS) patients often experiencing severe bleeding and anesthesia complications.3

There are limited previous reports of EDS patients undergoing mastectomy and/or breast reconstruction, and none wherein the patient had diagnoses of both vEDS and classical EDS (cEDS).5,6 Moreover, literature discussing surgical recommendations for EDS patients is sparse, with no comprehensive review of EDS breast reconstruction recommendations currently available.7-9 This report adds to the body of knowledge surrounding plastic surgery in EDS patients.

Case Report

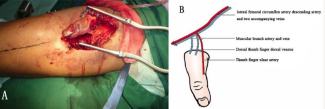

A 41-year-old female was referred to the plastic surgery clinic for breast reconstruction consultation after diagnosis of left breast lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), left breast atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH), left breast radial scar, and right breast pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia, diagnosed on core and needle biopsies. She has a past medical history of cEDS and vEDS with associated pectus carinatum, thoracic root dilation, and hypermobile joints (Figure 1) without multiple falls or injuries. Surgical history includes ovarian cyst removal, cholecystectomy, and rotator cuff surgery, all without complications. Family history includes breast cancer in her mother and maternal aunt, uterine cancer in her maternal first cousin, and thyroid cancer in her maternal grandmother. After shared decision making with the patient and her breast surgeon, it was decided the patient would benefit from bilateral prophylactic mastectomies with immediate 2-stage tissue expander reconstruction. There was no plan for adjuvant or neoadjuvant radiation, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy. Prior to surgery she met with both her cardiologist and rheumatologist regarding her EDS and was cleared for surgery.

The first stage of the patient’s 2-stage reconstruction began with bilateral skin sparing mastectomies performed by the breast surgeon. A left sentinel lymph node biopsy was also performed because the patient had 3 high-risk lesions within the left breast identified on imaging. The surgical pathology report for the left sentinel lymph nodes was negative for carcinoma. Right breast weight was 484 g. Left breast weight was 429 g. The mastectomies and lymph node biopsies were completed without complication.

The bilateral mastectomy skin flaps were irrigated, evaluated, and determined to be viable. The TE placement began with elevation of the lateral portion of the pectoralis major muscle anteriorly. The bilateral serratus anterior fascia was then elevated to create 2 identical pockets for expanders. The patient was noted to have a pectus carinatum. Surgicel powder was used and Blake drains were placed. The TE was then opened, deflated, and inserted in the correct orientation. The inferior lateral tabs of the TE were secured to the chest wall using 3-0 Vicryl. The pectoralis major was closed over the TE using 3-0 Vicryl. Next, 1-mm margins were excised around the skin edges and demonstrated good bleeding. Finally, the skin was approximated and sutured using 3-0 and 4-0 Biosyn in a running subcuticular fashion. For the dressings, Dermabond, Telfa, Tegaderm, and a breast binder were used. Other than the choice of 2-stage reconstruction, there was no adjustment to surgical approach, closure technique, or dressing choice because of this patient’s EDS. During TE placement, the patient was noted to have more than usual bleeding. Meticulous hemostasis was performed throughout the procedure. Estimated blood loss (EBL) was 50 mL. The patient was discharged the same day.

One week later, a small left-sided submuscular seroma was identified in clinic. Under aseptic technique, 25 mL of serous fluid was aspirated from around the left tissue expander. The patient tolerated this procedure well and the seroma resolved.

Tissue expansion began one month post mastectomy and TE placement. The patient was expanded to 400 mL on the right and 450 mL on the left over 7 months. The left TE was explanded to a larger size because of the asymmetry associated with her pectus carinatum deformity.

Eight months after her initial surgery, the patient was brought back to the operating room for tissue expander to implant exchange. The skin edges were excised in a 7-cm area from the prior mastectomy scar. The tissue expander was deflated and removed. A right-sided lateral capsulorrhaphy was performed using 2-0 V-Loc, and a right-sided superomedial capsulotomy was performed to make the breast pockets symmetrical. Two implants, 590 mL and 535 mL, were opened and inserted in the correct orientation for the left and right sides, respectively. Closure was done using 3-0 Vicryl, 3-0 Biosyn, and 4-0 Biosyn in a running subcuticular fashion. The patient was brought to sitting position, and there was excellent symmetry at the end of the procedure. A surgical bra was applied. The patient was discharged the same day, and the rest of the postoperative course was unremarkable.

Discussion

Surgical operations in patients with EDS pose a challenge due to the many possible complications as a result of abnormal collagen.3,4 This is especially true in patients with the classical and vascular subtypes of EDS. Hallmarks of cEDS are skin fragility and hyperextensibility, defective wound healing, and joint hypermobility, while vEDS hallmarks include easy bruising and exceedingly fragile blood vessels.3,7 If a patient has a combination of these 2 subtypes, it puts them at high risk for excessive blood loss and poor wound healing during and following surgery.

Despite these risks, the patient reported here had an unremarkable postoperative course. Her complications were limited to more than average bleeding during the first stage of reconstruction, which was easily managed with meticulous intraoperative hemostasis, and a small, uncomplicated submuscular seroma 1 week post operation. She had no complications following TE to implant exchange and continues to heal well.

The choice of 2-stage TE reconstruction method likely contributed to the positive outcome seen in this patient. Direct-to-implant (DTI) or autologous flap reconstruction are other popular surgical options in breast reconstruction. DTI reconstruction is often selected by patients at the time of mastectomy due to the many logistical benefits of only needing a single operation.10 However, DTI reconstruction has been associated with a higher risk of complications such as hematoma, seroma, and rippling.11 DTI also requires the use of acellular dermal matrix (ADM), an allograft scaffold, to help control the position of the implant and to aid in long-term soft-tissue support.12 Considering the increased tissue fragility, deficient wound healing, and increased overall complication risk in this patient, single-stage DTI was opted against. Autologous flap is another popular choice for breast reconstruction. Multiple options exist for these flaps, including superficially based abdominal flaps, medial thigh–based flaps, deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flaps, and thoracodorsal artery–based flaps.13,14 Autologous flaps avoid the complications associated with implants, such as capsular contracture, implant rupture, implant malposition, and infection, among others.15 Further, these patients typically achieve complete reconstruction faster than those undergoing expander or implant procedures.16 However, autologous reconstruction procedures are longer and more extensive, requiring secondary donor sites and, depending on the flap, vessel anastomosis. There is literature detailing a successful DIEP reconstruction in a patient with cEDS, but given our patient’s additional diagnosis of vEDS and the need for vessel anastomosis in DIEP reconstruction, our patient would likely be at higher risk for complications given her elevated vessel fragility.5 For these reasons, the more conservative 2-stage TE reconstruction method was chosen.

Conclusions

This case report documents a case in which a patient with both classical and vascular EDS had an unremarkable surgical and postoperative course following bilateral prophylactic mastectomies with 2-stage TE reconstruction.

Acknowledgments

Affiliations: 1USF Health Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida; 2FSU College of Medicine, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida; 3Department of Plastic Surgery, Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida

Correspondence: Timothy Nehila, BA; nehilat@usf.edu

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests.

References

1. Malfait F, Francomano C, Byers P, et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. Mar 2017;175(1):8-26. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31552

2. Mitchell AL, Schwarze U, Jennings JF, Byers PH. Molecular mechanisms of classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS). Hum Mutat. 2009;30(6):995-1002. doi:10.1002/humu.21000

3. Miller E, Grosel JM. A review of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. JAAPA. 2020;33(4):23-28. doi:10.1097/01.jaa.0000657160.48246.91

4. Kumar P, Sethi N, Friji MT, Poornima S. Wound healing and skin grafting in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(4):214e-215e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea935e

5. Creasy H, Bain C, Farhadi J. Free tissue transfer in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Microsurgery. 2017;37(5):455-456. doi:10.1002/micr.30067

6. Deshpande N, Murti S, Singh R, et al. Management of invasive ductal carcinoma in hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a case report. Gland Surg. 2021:2861-2866.

7. Wiesmann T, Castori M, Malfait F, Wulf H. Recommendations for anesthesia and perioperative management in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome(s). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:109. doi:10.1186/s13023-014-0109-5

8. Shirley ED, Demaio M, Bodurtha J. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in orthopaedics: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment implications. Sports Health. Sep 2012;4(5):394-403. doi:10.1177/1941738112452385

9. Joseph AW, Joseph SS, Francomano CA, Kontis TC. Characteristics, diagnosis, and management of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: a review. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(1):70-75. doi:10.1001/jamafacial.2017.0793

10. Perdanasari AT, Abu-Ghname A, Raj S, Winocour SJ, Largo RD. Update in direct-to-implant breast reconstruction. Semin Plast Surg. 2019;33(4):264-269. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1697028

11. Silva J, Carvalho F, Marques M. Direct-to-implant subcutaneous breast reconstruction: a systematic review of complications and patient's quality of life. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2023;47(1):92-105. doi:10.1007/s00266-022-03068-2

12. Colwell AS. Discussion: Comparing direct-to-implant and two-stage breast reconstruction in the Australian Breast Device Registry. Plast Reconst Surg. 2023;151(5):938-939. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000010067

13. Salibian AA, Patel KM. Microsurgery in oncoplastic breast reconstruction. Gland Surg. 2023;12(4):527-534. doi:10.21037/gs-22-561

14. Kevin P, Teotia SS, Haddock NT. To ablate or not to ablate: the question if umbilectomy decreases donor site complications in DIEP flap breast reconstruction?. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;doi:10.1097/prs.0000000000010617

15. Haddock NT, Suszynski TM, Teotia SS. An individualized patient-centric approach and evolution towards total autologous free flap breast reconstruction in an academic setting. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(4):e2681. doi:10.1097/gox.0000000000002681

16. Fischer JP, Nelson JA, Cleveland E, et al. Breast reconstruction modality outcome study: a comparison of expander/implants and free flaps in select patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(5):928-934. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182865977