Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, talks about new eczema medications, his research, and the importance of primary care providers understanding how impactful AD can be.

What’s the greatest challenge to treating people who have eczema? Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, replied without hesitation: “The itch. It’s all about the itch,” said Dr Sidbury, who is the chief of the division of dermatology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, and a professor in the department of pediatrics, in an interview with The Dermatologist. “Of course, there’s also the visible rash, the infection risk, the constant dryness, the hypersensitivity, and an array of associated comorbidities such as allergies, asthma, hay fever, and more—all of which are no picnic to be sure—but, the itch is where it all starts. It is distracting, painful, disruptive to sleep, school, and fun—and at times all-encompassing,” he said.

What’s the greatest challenge to treating people who have eczema? Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, replied without hesitation: “The itch. It’s all about the itch,” said Dr Sidbury, who is the chief of the division of dermatology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, and a professor in the department of pediatrics, in an interview with The Dermatologist. “Of course, there’s also the visible rash, the infection risk, the constant dryness, the hypersensitivity, and an array of associated comorbidities such as allergies, asthma, hay fever, and more—all of which are no picnic to be sure—but, the itch is where it all starts. It is distracting, painful, disruptive to sleep, school, and fun—and at times all-encompassing,” he said.

He pointed out that those “all encompassing” effects were revealed in the National Eczema Association’s (NEA) Burden of Disease Audit,1 which it commissioned last year. “The NEA’s audit helped us understand just how much moderate to severe eczema impacts patients and in what ways,” said Dr Sidbury, who described the NEA as a valuable organization. “This has been true for many years as it has been a source of guidance, support, and advocacy for a disease that otherwise suffered from a dearth of all of the above.” He stressed that the essential function of NEA is even more apparent now in the age of exciting new medications for eczema and atopic dermatitis (AD). “New medications, of course, are not inexpensive, but the NEA aims to help all stakeholders find common ground and maximum access,” he said.

________________________________________________________________________

Related Content

Understanding Itch

Study: Patients with AD Experience Daily Life Burden, Lower QoL

________________________________________________________________________

During the interview, Dr Sidbury talked about the new medications, his research, and the importance of primary care providers understanding how impactful AD can be.

Q. What sparked your interest in dermatology as a profession and eczema as the focus of your research and practice?

a. I did a dermatology rotation in the spring semester of my final year in medical school—out of curiosity more than anything else. That was all it took. Dermatology was a wonderful amalgam of all that I had liked about medical school up to that point: medicine, surgery, and pathology. Training with Jon Hanifin, MD, and Amy Paller, MD, exposed me to what an impactful disease eczema can be and what a complex and scientifically interesting disease it is.

Q. What are some of the eczema/AD advances that you are excited about and why?

a. Therapeutically there has been an explosion of interest in AD from pharmaceutical companies, as science has better characterized the nature of atopic inflammation. In the last few months alone, the new nonsteroidal topical medication—crisaborole (Eucrisa, Pfizer), and a new biologic systemic medication—dupilumab (Dipixent, Sanofi Regeneron), have been FDA approved for AD. It is also exciting that recent epidemiologic studies have taught us about new comorbidities to be aware of beyond the typical atopic march—food allergies, asthma, and hay fever.2 For instance, conditions as diverse as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anemia, and obesity have all been linked to AD.3-5

Q. Can you provide some highlights of your recent research for our readers?

a. Vitamin D and its protean impacts on health has long been an interest of mine. A couple of years back we published a randomized trial looking at vitamin D supplementation for AD in Mongolia.6 I practice in Seattle where most people are low on vitamin D in the wintertime so supplementation, for AD or just good health, is usually a good idea.

Another recent development has been the flipped script with regard to peanut allergy prevention. Historically, we have told caregivers of atopic infants and children to ensure that they avoid peanuts in order to avoid developing peanut allergy. This may have been exactly backwards as the rates of peanut allergy have gone continually up over the years. A recent study, the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy trial, showed that early exposure to peanut protein in appropriate individuals may actually decrease rates of peanut allergy.7 I was privileged to participate in an expert panel assembled by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to incorporate this new data on peanuts into actionable guidelines.8 It will be interesting to see how this story evolves with regard not only to peanuts, but other potentially allergenic foods.

Q. What are some areas/therapies that offer patients with eczema/AD the most promise?

a. Topical steroids are still first-line therapy, and topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) are wonderful second-line nonsteroidal options; and newer studies and information generated from long-term registries have been reassuring regarding their safety. While topical steroids and TCIs are first- and second-line therapies and will continue to help affected patients, areas that offer the most promise include some of these newer more targeted medications, such as IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31, to name a few. They will specifically target the chemical foot soldiers of atopic inflammation. By more specifically targeting AD cytokines instead of nonspecifically muting the entire inflammatory response—much of which is salutary and, among other things, helps fight infections—we will hopefully see better benefit/risk profiles.

Q. What does the future landscape of eczema/AD look like?

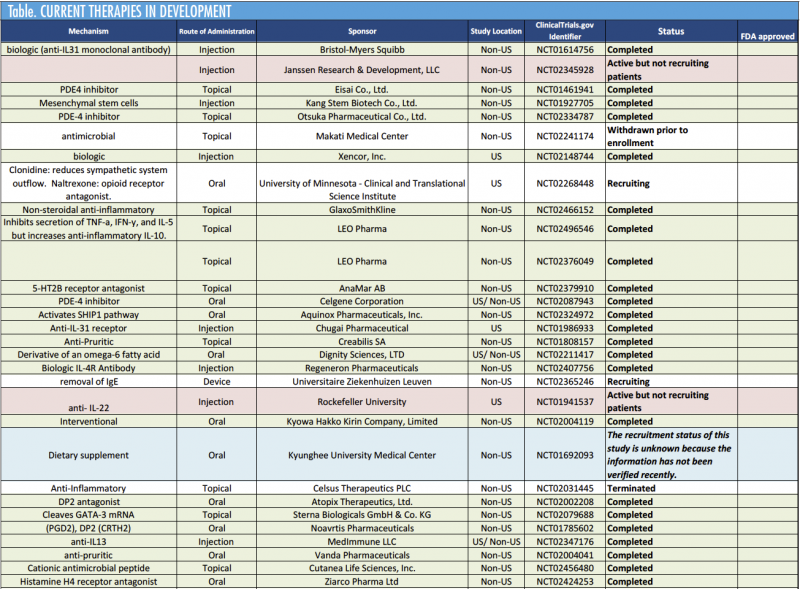

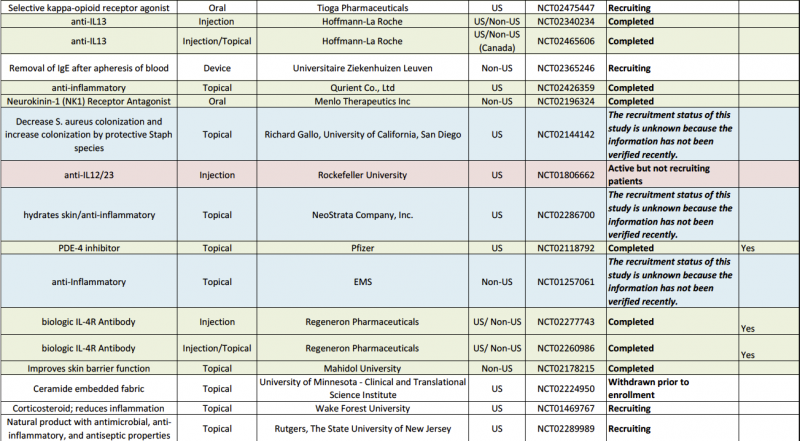

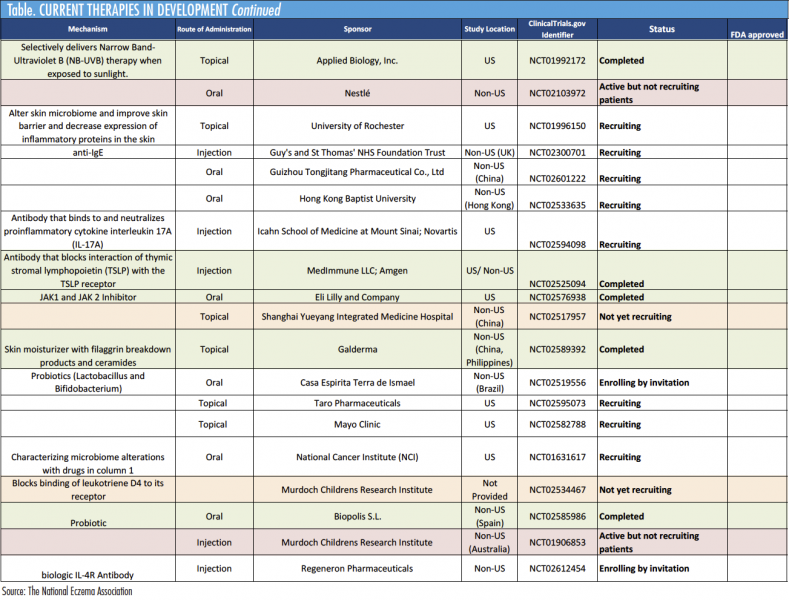

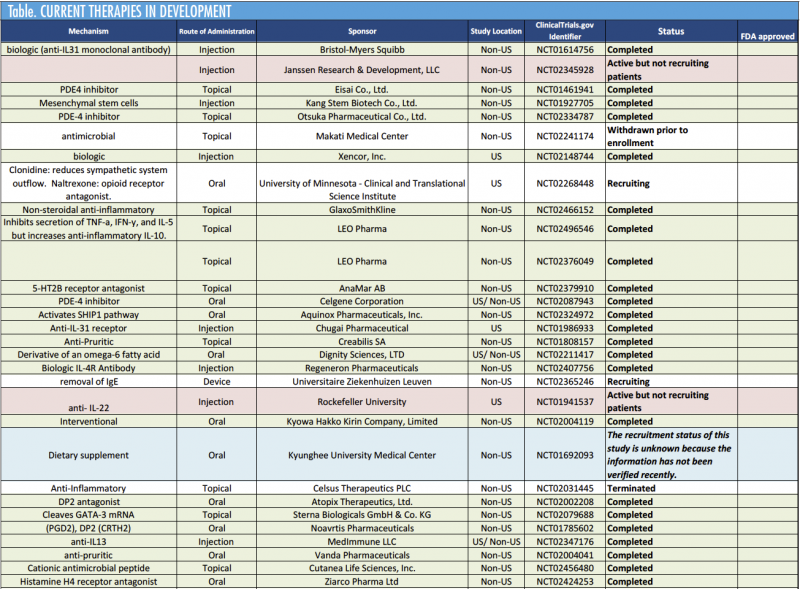

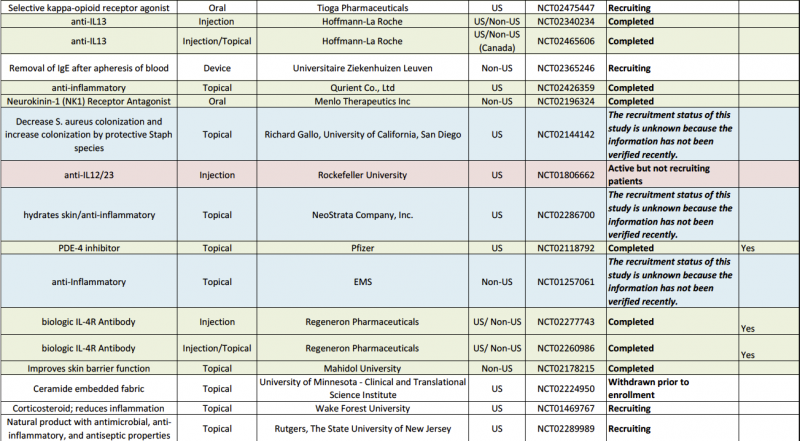

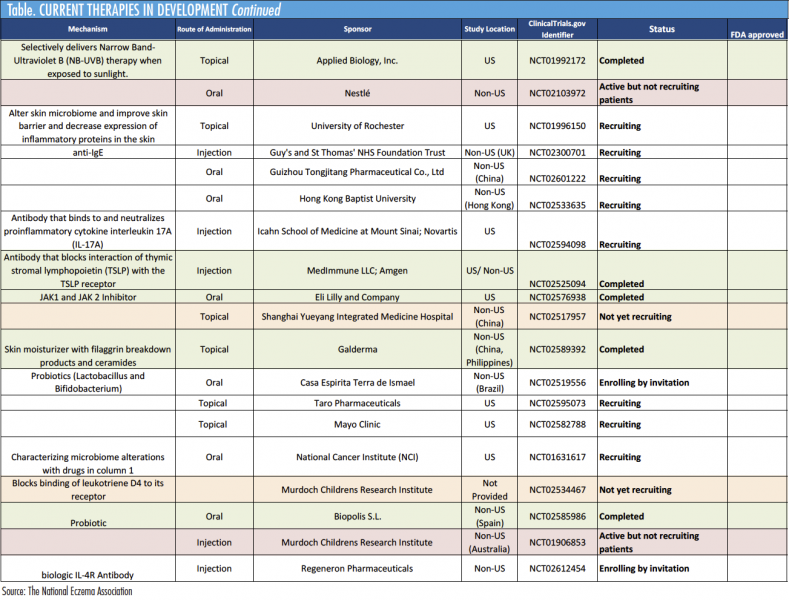

a. The future includes more and better targeted therapy. One need only look at the pipeline for drugs currently being investigated, from different phosphodiesterase inhibitors, to entirely different molecules of interest, such as IL-31 blockers, to see the promise that lies ahead for better treatment options (Table on Page 3).

Q. What is the greatest challenge in treating children who have eczema?

a. The itch. For those who do not have eczema but have contracted poison oak/ivy, or gotten bad bug bites, or developed a contact allergy—they know just how noxious itch can be for even a day or so. Children with bad eczema itch 24/7. This is why comparative assessments of chronic disease show bad AD to be more impactful than diseases such as diabetes. That such a statement is surprising to many—even to some primary care providers who brush off this disease as “just” eczema—adds insult to injury and is another reason this disease can be so vexing.

References

1. Drucker AM, Wang AR, Qureshi AA. Research gaps in quality of life and economic burden of atopic dermatitis: The National Eczema Association Burden of Disease Audit. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(8):873-874.

2. Schneider L, Hanifin J, Boguniewicz M, et al. Study of the atopic march: Development of atopic comorbidities. Pediatric Dermatology. 2016;33(4):388-398.

3. Nygaard U, Riis JL, Deleuran M, Vestergaard C. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in atopic dermatitis: an appraisal of the current literature. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2016;29(4):181-188.

4. Drury KE, Schaeffer M, Silverberg JI. Association between atopic disease and anemia in US children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):29-34.

5. Zhang A, Silverberg JL. Association of atopic dermatitis with being overweight and obese: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(4):606-616.

6. Camargo CA Jr, Ganmaa D, Sidbury R, Erdenedelger K, Radnaakhand N, Khandsuren B. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation for winter-related atopic dermatitis in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):831-835.e1.

7. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):803-813.

8. Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: summary of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-sponsored expert panel. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(1):5-12.

Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, talks about new eczema medications, his research, and the importance of primary care providers understanding how impactful AD can be.

What’s the greatest challenge to treating people who have eczema? Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, replied without hesitation: “The itch. It’s all about the itch,” said Dr Sidbury, who is the chief of the division of dermatology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, and a professor in the department of pediatrics, in an interview with The Dermatologist. “Of course, there’s also the visible rash, the infection risk, the constant dryness, the hypersensitivity, and an array of associated comorbidities such as allergies, asthma, hay fever, and more—all of which are no picnic to be sure—but, the itch is where it all starts. It is distracting, painful, disruptive to sleep, school, and fun—and at times all-encompassing,” he said.

What’s the greatest challenge to treating people who have eczema? Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, replied without hesitation: “The itch. It’s all about the itch,” said Dr Sidbury, who is the chief of the division of dermatology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, and a professor in the department of pediatrics, in an interview with The Dermatologist. “Of course, there’s also the visible rash, the infection risk, the constant dryness, the hypersensitivity, and an array of associated comorbidities such as allergies, asthma, hay fever, and more—all of which are no picnic to be sure—but, the itch is where it all starts. It is distracting, painful, disruptive to sleep, school, and fun—and at times all-encompassing,” he said.

He pointed out that those “all encompassing” effects were revealed in the National Eczema Association’s (NEA) Burden of Disease Audit,1 which it commissioned last year. “The NEA’s audit helped us understand just how much moderate to severe eczema impacts patients and in what ways,” said Dr Sidbury, who described the NEA as a valuable organization. “This has been true for many years as it has been a source of guidance, support, and advocacy for a disease that otherwise suffered from a dearth of all of the above.” He stressed that the essential function of NEA is even more apparent now in the age of exciting new medications for eczema and atopic dermatitis (AD). “New medications, of course, are not inexpensive, but the NEA aims to help all stakeholders find common ground and maximum access,” he said.

________________________________________________________________________

Related Content

Understanding Itch

Study: Patients with AD Experience Daily Life Burden, Lower QoL

________________________________________________________________________

During the interview, Dr Sidbury talked about the new medications, his research, and the importance of primary care providers understanding how impactful AD can be.

Q. What sparked your interest in dermatology as a profession and eczema as the focus of your research and practice?

a. I did a dermatology rotation in the spring semester of my final year in medical school—out of curiosity more than anything else. That was all it took. Dermatology was a wonderful amalgam of all that I had liked about medical school up to that point: medicine, surgery, and pathology. Training with Jon Hanifin, MD, and Amy Paller, MD, exposed me to what an impactful disease eczema can be and what a complex and scientifically interesting disease it is.

Q. What are some of the eczema/AD advances that you are excited about and why?

a. Therapeutically there has been an explosion of interest in AD from pharmaceutical companies, as science has better characterized the nature of atopic inflammation. In the last few months alone, the new nonsteroidal topical medication—crisaborole (Eucrisa, Pfizer), and a new biologic systemic medication—dupilumab (Dipixent, Sanofi Regeneron), have been FDA approved for AD. It is also exciting that recent epidemiologic studies have taught us about new comorbidities to be aware of beyond the typical atopic march—food allergies, asthma, and hay fever.2 For instance, conditions as diverse as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anemia, and obesity have all been linked to AD.3-5

Q. Can you provide some highlights of your recent research for our readers?

a. Vitamin D and its protean impacts on health has long been an interest of mine. A couple of years back we published a randomized trial looking at vitamin D supplementation for AD in Mongolia.6 I practice in Seattle where most people are low on vitamin D in the wintertime so supplementation, for AD or just good health, is usually a good idea.

Another recent development has been the flipped script with regard to peanut allergy prevention. Historically, we have told caregivers of atopic infants and children to ensure that they avoid peanuts in order to avoid developing peanut allergy. This may have been exactly backwards as the rates of peanut allergy have gone continually up over the years. A recent study, the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy trial, showed that early exposure to peanut protein in appropriate individuals may actually decrease rates of peanut allergy.7 I was privileged to participate in an expert panel assembled by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to incorporate this new data on peanuts into actionable guidelines.8 It will be interesting to see how this story evolves with regard not only to peanuts, but other potentially allergenic foods.

Q. What are some areas/therapies that offer patients with eczema/AD the most promise?

a. Topical steroids are still first-line therapy, and topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) are wonderful second-line nonsteroidal options; and newer studies and information generated from long-term registries have been reassuring regarding their safety. While topical steroids and TCIs are first- and second-line therapies and will continue to help affected patients, areas that offer the most promise include some of these newer more targeted medications, such as IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31, to name a few. They will specifically target the chemical foot soldiers of atopic inflammation. By more specifically targeting AD cytokines instead of nonspecifically muting the entire inflammatory response—much of which is salutary and, among other things, helps fight infections—we will hopefully see better benefit/risk profiles.

Q. What does the future landscape of eczema/AD look like?

a. The future includes more and better targeted therapy. One need only look at the pipeline for drugs currently being investigated, from different phosphodiesterase inhibitors, to entirely different molecules of interest, such as IL-31 blockers, to see the promise that lies ahead for better treatment options (Table on Page 3).

Q. What is the greatest challenge in treating children who have eczema?

a. The itch. For those who do not have eczema but have contracted poison oak/ivy, or gotten bad bug bites, or developed a contact allergy—they know just how noxious itch can be for even a day or so. Children with bad eczema itch 24/7. This is why comparative assessments of chronic disease show bad AD to be more impactful than diseases such as diabetes. That such a statement is surprising to many—even to some primary care providers who brush off this disease as “just” eczema—adds insult to injury and is another reason this disease can be so vexing.

References

1. Drucker AM, Wang AR, Qureshi AA. Research gaps in quality of life and economic burden of atopic dermatitis: The National Eczema Association Burden of Disease Audit. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(8):873-874.

2. Schneider L, Hanifin J, Boguniewicz M, et al. Study of the atopic march: Development of atopic comorbidities. Pediatric Dermatology. 2016;33(4):388-398.

3. Nygaard U, Riis JL, Deleuran M, Vestergaard C. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in atopic dermatitis: an appraisal of the current literature. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2016;29(4):181-188.

4. Drury KE, Schaeffer M, Silverberg JI. Association between atopic disease and anemia in US children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):29-34.

5. Zhang A, Silverberg JL. Association of atopic dermatitis with being overweight and obese: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(4):606-616.

6. Camargo CA Jr, Ganmaa D, Sidbury R, Erdenedelger K, Radnaakhand N, Khandsuren B. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation for winter-related atopic dermatitis in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):831-835.e1.

7. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):803-813.

8. Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: summary of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-sponsored expert panel. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(1):5-12.

Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, talks about new eczema medications, his research, and the importance of primary care providers understanding how impactful AD can be.

What’s the greatest challenge to treating people who have eczema? Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, replied without hesitation: “The itch. It’s all about the itch,” said Dr Sidbury, who is the chief of the division of dermatology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, and a professor in the department of pediatrics, in an interview with The Dermatologist. “Of course, there’s also the visible rash, the infection risk, the constant dryness, the hypersensitivity, and an array of associated comorbidities such as allergies, asthma, hay fever, and more—all of which are no picnic to be sure—but, the itch is where it all starts. It is distracting, painful, disruptive to sleep, school, and fun—and at times all-encompassing,” he said.

What’s the greatest challenge to treating people who have eczema? Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, replied without hesitation: “The itch. It’s all about the itch,” said Dr Sidbury, who is the chief of the division of dermatology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, and a professor in the department of pediatrics, in an interview with The Dermatologist. “Of course, there’s also the visible rash, the infection risk, the constant dryness, the hypersensitivity, and an array of associated comorbidities such as allergies, asthma, hay fever, and more—all of which are no picnic to be sure—but, the itch is where it all starts. It is distracting, painful, disruptive to sleep, school, and fun—and at times all-encompassing,” he said.

He pointed out that those “all encompassing” effects were revealed in the National Eczema Association’s (NEA) Burden of Disease Audit,1 which it commissioned last year. “The NEA’s audit helped us understand just how much moderate to severe eczema impacts patients and in what ways,” said Dr Sidbury, who described the NEA as a valuable organization. “This has been true for many years as it has been a source of guidance, support, and advocacy for a disease that otherwise suffered from a dearth of all of the above.” He stressed that the essential function of NEA is even more apparent now in the age of exciting new medications for eczema and atopic dermatitis (AD). “New medications, of course, are not inexpensive, but the NEA aims to help all stakeholders find common ground and maximum access,” he said.

________________________________________________________________________

Related Content

Understanding Itch

Study: Patients with AD Experience Daily Life Burden, Lower QoL

________________________________________________________________________

During the interview, Dr Sidbury talked about the new medications, his research, and the importance of primary care providers understanding how impactful AD can be.

Q. What sparked your interest in dermatology as a profession and eczema as the focus of your research and practice?

a. I did a dermatology rotation in the spring semester of my final year in medical school—out of curiosity more than anything else. That was all it took. Dermatology was a wonderful amalgam of all that I had liked about medical school up to that point: medicine, surgery, and pathology. Training with Jon Hanifin, MD, and Amy Paller, MD, exposed me to what an impactful disease eczema can be and what a complex and scientifically interesting disease it is.

Q. What are some of the eczema/AD advances that you are excited about and why?

a. Therapeutically there has been an explosion of interest in AD from pharmaceutical companies, as science has better characterized the nature of atopic inflammation. In the last few months alone, the new nonsteroidal topical medication—crisaborole (Eucrisa, Pfizer), and a new biologic systemic medication—dupilumab (Dipixent, Sanofi Regeneron), have been FDA approved for AD. It is also exciting that recent epidemiologic studies have taught us about new comorbidities to be aware of beyond the typical atopic march—food allergies, asthma, and hay fever.2 For instance, conditions as diverse as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anemia, and obesity have all been linked to AD.3-5

Q. Can you provide some highlights of your recent research for our readers?

a. Vitamin D and its protean impacts on health has long been an interest of mine. A couple of years back we published a randomized trial looking at vitamin D supplementation for AD in Mongolia.6 I practice in Seattle where most people are low on vitamin D in the wintertime so supplementation, for AD or just good health, is usually a good idea.

Another recent development has been the flipped script with regard to peanut allergy prevention. Historically, we have told caregivers of atopic infants and children to ensure that they avoid peanuts in order to avoid developing peanut allergy. This may have been exactly backwards as the rates of peanut allergy have gone continually up over the years. A recent study, the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy trial, showed that early exposure to peanut protein in appropriate individuals may actually decrease rates of peanut allergy.7 I was privileged to participate in an expert panel assembled by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to incorporate this new data on peanuts into actionable guidelines.8 It will be interesting to see how this story evolves with regard not only to peanuts, but other potentially allergenic foods.

Q. What are some areas/therapies that offer patients with eczema/AD the most promise?

a. Topical steroids are still first-line therapy, and topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) are wonderful second-line nonsteroidal options; and newer studies and information generated from long-term registries have been reassuring regarding their safety. While topical steroids and TCIs are first- and second-line therapies and will continue to help affected patients, areas that offer the most promise include some of these newer more targeted medications, such as IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31, to name a few. They will specifically target the chemical foot soldiers of atopic inflammation. By more specifically targeting AD cytokines instead of nonspecifically muting the entire inflammatory response—much of which is salutary and, among other things, helps fight infections—we will hopefully see better benefit/risk profiles.

Q. What does the future landscape of eczema/AD look like?

a. The future includes more and better targeted therapy. One need only look at the pipeline for drugs currently being investigated, from different phosphodiesterase inhibitors, to entirely different molecules of interest, such as IL-31 blockers, to see the promise that lies ahead for better treatment options (Table on Page 3).

Q. What is the greatest challenge in treating children who have eczema?

a. The itch. For those who do not have eczema but have contracted poison oak/ivy, or gotten bad bug bites, or developed a contact allergy—they know just how noxious itch can be for even a day or so. Children with bad eczema itch 24/7. This is why comparative assessments of chronic disease show bad AD to be more impactful than diseases such as diabetes. That such a statement is surprising to many—even to some primary care providers who brush off this disease as “just” eczema—adds insult to injury and is another reason this disease can be so vexing.

References

1. Drucker AM, Wang AR, Qureshi AA. Research gaps in quality of life and economic burden of atopic dermatitis: The National Eczema Association Burden of Disease Audit. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(8):873-874.

2. Schneider L, Hanifin J, Boguniewicz M, et al. Study of the atopic march: Development of atopic comorbidities. Pediatric Dermatology. 2016;33(4):388-398.

3. Nygaard U, Riis JL, Deleuran M, Vestergaard C. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in atopic dermatitis: an appraisal of the current literature. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2016;29(4):181-188.

4. Drury KE, Schaeffer M, Silverberg JI. Association between atopic disease and anemia in US children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):29-34.

5. Zhang A, Silverberg JL. Association of atopic dermatitis with being overweight and obese: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(4):606-616.

6. Camargo CA Jr, Ganmaa D, Sidbury R, Erdenedelger K, Radnaakhand N, Khandsuren B. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation for winter-related atopic dermatitis in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):831-835.e1.

7. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):803-813.

8. Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: summary of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-sponsored expert panel. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(1):5-12.

What’s the greatest challenge to treating people who have eczema? Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, replied without hesitation: “The itch. It’s all about the itch,” said Dr Sidbury, who is the chief of the division of dermatology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, and a professor in the department of pediatrics, in an interview with The Dermatologist. “Of course, there’s also the visible rash, the infection risk, the constant dryness, the hypersensitivity, and an array of associated comorbidities such as allergies, asthma, hay fever, and more—all of which are no picnic to be sure—but, the itch is where it all starts. It is distracting, painful, disruptive to sleep, school, and fun—and at times all-encompassing,” he said.

What’s the greatest challenge to treating people who have eczema? Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, replied without hesitation: “The itch. It’s all about the itch,” said Dr Sidbury, who is the chief of the division of dermatology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, and a professor in the department of pediatrics, in an interview with The Dermatologist. “Of course, there’s also the visible rash, the infection risk, the constant dryness, the hypersensitivity, and an array of associated comorbidities such as allergies, asthma, hay fever, and more—all of which are no picnic to be sure—but, the itch is where it all starts. It is distracting, painful, disruptive to sleep, school, and fun—and at times all-encompassing,” he said.

What’s the greatest challenge to treating people who have eczema? Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, replied without hesitation: “The itch. It’s all about the itch,” said Dr Sidbury, who is the chief of the division of dermatology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, and a professor in the department of pediatrics, in an interview with The Dermatologist. “Of course, there’s also the visible rash, the infection risk, the constant dryness, the hypersensitivity, and an array of associated comorbidities such as allergies, asthma, hay fever, and more—all of which are no picnic to be sure—but, the itch is where it all starts. It is distracting, painful, disruptive to sleep, school, and fun—and at times all-encompassing,” he said.

What’s the greatest challenge to treating people who have eczema? Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, replied without hesitation: “The itch. It’s all about the itch,” said Dr Sidbury, who is the chief of the division of dermatology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of Medicine, and a professor in the department of pediatrics, in an interview with The Dermatologist. “Of course, there’s also the visible rash, the infection risk, the constant dryness, the hypersensitivity, and an array of associated comorbidities such as allergies, asthma, hay fever, and more—all of which are no picnic to be sure—but, the itch is where it all starts. It is distracting, painful, disruptive to sleep, school, and fun—and at times all-encompassing,” he said.