This case reports on a rare case of radiation-induced lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC) in a 68-year-old woman with a history of Hodgkin lymphoma, treated with radiation therapy to the groin and stem cell transplant 9 years prior to dermatologic evaluation. The patient reported chronic lymphedema of the groin with occasional clear drainage for years following radiation therapy.

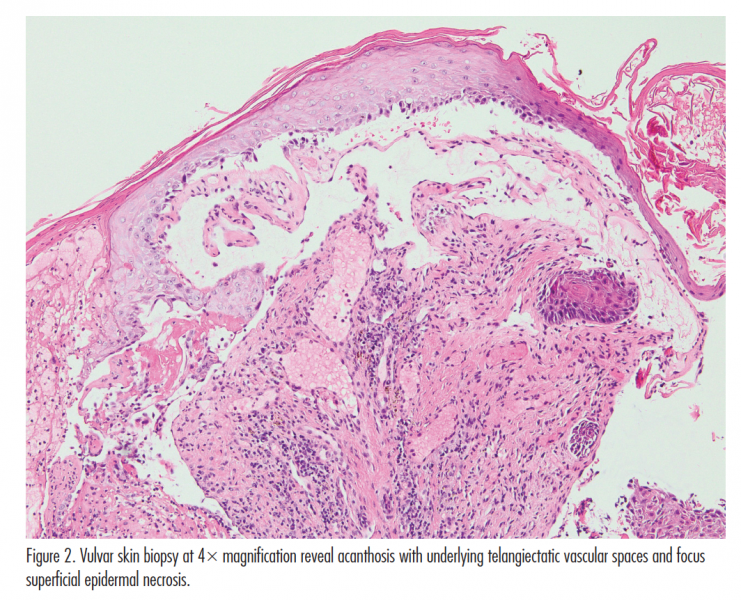

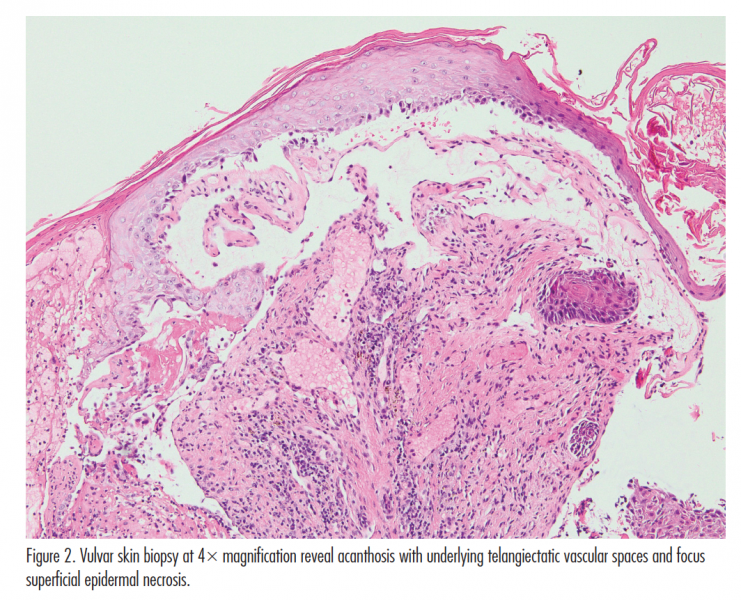

At initial presentation, the patient reported a 6-month history of painful and pruritic “pink bumps and blisters” on the bilateral labia majora with continuous weeping of clear lymphatic drainage. Trial of topical antibiotics, hydrocortisone, and valacyclovir did not improve her lesions. On examination, pink papillomatous plaques with scattered intact and weeping vesicles were noted on the bilateral anterior superior external labia majora (Figure 1A). A skin biopsy of the lesions revealed acanthotic hyperkeratotic epidermis with underlying telangiectatic vascular spaces and focal superficial epidermal necrosis (Figure 1B) consistent with LC. Herpes simplex virus 1/2 immunohistochemical staining of the biopsied skin was negative and neither dysplasia nor malignancy were noted. The patient underwent fractionated carbon dioxide (CO2) laser ablation and 1-month follow-up showed considerable improvement, and no local recurrence nor postprocedure complications (Figure 2).

Article continues on page 2

{{pagebreak}}

Discussion

LC involves the most superficial layers of the skin and can be categorized as congenital LC, caused by a developmental defect of dermal lymphatic tissues, and acquired LC, by lymphatic channel damage leading to obstruction.1 Of the 67 cases of acquired LC reported, 41 patients (61%) had a history of malignancy and 31 of these patients had undergone radiation therapy.2

As seen in this case, clustered vesicles that resemble frog-spawn with oozing clear fluid or lymphorrhea are commonly seen. Sometimes lesions may present as hyperkeratotic verrucous papules that can be mistaken for genital warts, or fleshy, polyploid in appearance, resembling condyloma acuminata.1 Herpes zoster, molluscum contagiousum, fungal infections, and leiomyoma are in the differential diagnosis.3 Because patients with radiation to the groin can develop chronic edema, lymphangiosarcoma and recurrent or metastatic gynecologic malignancies are of concern, but can be distinguished from vulvar LC by their histopathologic features. Of note, there are no reports of malignant transformation of vulvar LC.3

Skin biopsy shows a circumscribed area of involvement with hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and papillomatosis of the epidermis and a dermal papillary layer with dilated thin-wall lymphatics filled with pale secretions. Lymphatic channels can be confirmed with lymphatic endothelial marker D2-40.1,4

Currently, no consensus exists regarding a standardized treatment for LC. Surgical excision remains the preferred treatment with low recurrence of disease in small lesions when the excision includes responsible lymphatic vessels.5 Nonsurgical options such as cryotherapy and sclerotherapy show low remission and high recurrence rates.

In contrast, CO2 lasers have been shown to be effective treatment modalities for larger vulvar LC lesions and in patients with treatment failure after other nonsurgical treatments. CO2 lasers are hypothesized to work through vaporization of the abnormal lymphatics and by sealing off deeper lymphatic channels. While our patient has responded well thus far, she will require follow-up given focal recurrence at 1 year that has been noted.5

Ms Pouldar is with the division of dermatology at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Hisaw is with the division of dermatology at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Turegano is with the division of dermatopathology, department of pathology and laboratory medicine, at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Vardanian is with the division of plastic and reconstructive surgery, department of surgery at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Young is with the division of dermatology at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Disclosure: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Gnanaraj P, Revathy V, Venugopal V, Tamilchelvan D, Rajagopalan V. Secondary lymphangioma of vulva: a report of two cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57(2):149-151.

2. Chang MB, Newman CC, Davis MD, Lehman JS. Acquired lymphangiectasia (lymphangioma circumscriptum) of the vulva: Clinicopathologic study of 11 patients from a single institution and 67 from the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55(9):e482-497.

3. Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Burchette JL, Foo WC, Selim MA. Acquired vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a comparison of 12 cases with Crohn’s associated lesions or radiation therapy induced tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(9):958-965.

4. Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94(5):473-486.

5. Huilgol SC, Neill S, Barlow RJ. CO(2) laser therapy of vulval lymphangiectasia and lymphangioma circumscriptum. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(7):575-577.

This case reports on a rare case of radiation-induced lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC) in a 68-year-old woman with a history of Hodgkin lymphoma, treated with radiation therapy to the groin and stem cell transplant 9 years prior to dermatologic evaluation. The patient reported chronic lymphedema of the groin with occasional clear drainage for years following radiation therapy.

At initial presentation, the patient reported a 6-month history of painful and pruritic “pink bumps and blisters” on the bilateral labia majora with continuous weeping of clear lymphatic drainage. Trial of topical antibiotics, hydrocortisone, and valacyclovir did not improve her lesions. On examination, pink papillomatous plaques with scattered intact and weeping vesicles were noted on the bilateral anterior superior external labia majora (Figure 1A). A skin biopsy of the lesions revealed acanthotic hyperkeratotic epidermis with underlying telangiectatic vascular spaces and focal superficial epidermal necrosis (Figure 1B) consistent with LC. Herpes simplex virus 1/2 immunohistochemical staining of the biopsied skin was negative and neither dysplasia nor malignancy were noted. The patient underwent fractionated carbon dioxide (CO2) laser ablation and 1-month follow-up showed considerable improvement, and no local recurrence nor postprocedure complications (Figure 2).

Article continues on page 2

{{pagebreak}}

Discussion

LC involves the most superficial layers of the skin and can be categorized as congenital LC, caused by a developmental defect of dermal lymphatic tissues, and acquired LC, by lymphatic channel damage leading to obstruction.1 Of the 67 cases of acquired LC reported, 41 patients (61%) had a history of malignancy and 31 of these patients had undergone radiation therapy.2

As seen in this case, clustered vesicles that resemble frog-spawn with oozing clear fluid or lymphorrhea are commonly seen. Sometimes lesions may present as hyperkeratotic verrucous papules that can be mistaken for genital warts, or fleshy, polyploid in appearance, resembling condyloma acuminata.1 Herpes zoster, molluscum contagiousum, fungal infections, and leiomyoma are in the differential diagnosis.3 Because patients with radiation to the groin can develop chronic edema, lymphangiosarcoma and recurrent or metastatic gynecologic malignancies are of concern, but can be distinguished from vulvar LC by their histopathologic features. Of note, there are no reports of malignant transformation of vulvar LC.3

Skin biopsy shows a circumscribed area of involvement with hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and papillomatosis of the epidermis and a dermal papillary layer with dilated thin-wall lymphatics filled with pale secretions. Lymphatic channels can be confirmed with lymphatic endothelial marker D2-40.1,4

Currently, no consensus exists regarding a standardized treatment for LC. Surgical excision remains the preferred treatment with low recurrence of disease in small lesions when the excision includes responsible lymphatic vessels.5 Nonsurgical options such as cryotherapy and sclerotherapy show low remission and high recurrence rates.

In contrast, CO2 lasers have been shown to be effective treatment modalities for larger vulvar LC lesions and in patients with treatment failure after other nonsurgical treatments. CO2 lasers are hypothesized to work through vaporization of the abnormal lymphatics and by sealing off deeper lymphatic channels. While our patient has responded well thus far, she will require follow-up given focal recurrence at 1 year that has been noted.5

Ms Pouldar is with the division of dermatology at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Hisaw is with the division of dermatology at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Turegano is with the division of dermatopathology, department of pathology and laboratory medicine, at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Vardanian is with the division of plastic and reconstructive surgery, department of surgery at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Young is with the division of dermatology at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Disclosure: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Gnanaraj P, Revathy V, Venugopal V, Tamilchelvan D, Rajagopalan V. Secondary lymphangioma of vulva: a report of two cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57(2):149-151.

2. Chang MB, Newman CC, Davis MD, Lehman JS. Acquired lymphangiectasia (lymphangioma circumscriptum) of the vulva: Clinicopathologic study of 11 patients from a single institution and 67 from the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55(9):e482-497.

3. Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Burchette JL, Foo WC, Selim MA. Acquired vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a comparison of 12 cases with Crohn’s associated lesions or radiation therapy induced tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(9):958-965.

4. Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94(5):473-486.

5. Huilgol SC, Neill S, Barlow RJ. CO(2) laser therapy of vulval lymphangiectasia and lymphangioma circumscriptum. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(7):575-577.

This case reports on a rare case of radiation-induced lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC) in a 68-year-old woman with a history of Hodgkin lymphoma, treated with radiation therapy to the groin and stem cell transplant 9 years prior to dermatologic evaluation. The patient reported chronic lymphedema of the groin with occasional clear drainage for years following radiation therapy.

At initial presentation, the patient reported a 6-month history of painful and pruritic “pink bumps and blisters” on the bilateral labia majora with continuous weeping of clear lymphatic drainage. Trial of topical antibiotics, hydrocortisone, and valacyclovir did not improve her lesions. On examination, pink papillomatous plaques with scattered intact and weeping vesicles were noted on the bilateral anterior superior external labia majora (Figure 1A). A skin biopsy of the lesions revealed acanthotic hyperkeratotic epidermis with underlying telangiectatic vascular spaces and focal superficial epidermal necrosis (Figure 1B) consistent with LC. Herpes simplex virus 1/2 immunohistochemical staining of the biopsied skin was negative and neither dysplasia nor malignancy were noted. The patient underwent fractionated carbon dioxide (CO2) laser ablation and 1-month follow-up showed considerable improvement, and no local recurrence nor postprocedure complications (Figure 2).

Article continues on page 2

{{pagebreak}}

Discussion

LC involves the most superficial layers of the skin and can be categorized as congenital LC, caused by a developmental defect of dermal lymphatic tissues, and acquired LC, by lymphatic channel damage leading to obstruction.1 Of the 67 cases of acquired LC reported, 41 patients (61%) had a history of malignancy and 31 of these patients had undergone radiation therapy.2

As seen in this case, clustered vesicles that resemble frog-spawn with oozing clear fluid or lymphorrhea are commonly seen. Sometimes lesions may present as hyperkeratotic verrucous papules that can be mistaken for genital warts, or fleshy, polyploid in appearance, resembling condyloma acuminata.1 Herpes zoster, molluscum contagiousum, fungal infections, and leiomyoma are in the differential diagnosis.3 Because patients with radiation to the groin can develop chronic edema, lymphangiosarcoma and recurrent or metastatic gynecologic malignancies are of concern, but can be distinguished from vulvar LC by their histopathologic features. Of note, there are no reports of malignant transformation of vulvar LC.3

Skin biopsy shows a circumscribed area of involvement with hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and papillomatosis of the epidermis and a dermal papillary layer with dilated thin-wall lymphatics filled with pale secretions. Lymphatic channels can be confirmed with lymphatic endothelial marker D2-40.1,4

Currently, no consensus exists regarding a standardized treatment for LC. Surgical excision remains the preferred treatment with low recurrence of disease in small lesions when the excision includes responsible lymphatic vessels.5 Nonsurgical options such as cryotherapy and sclerotherapy show low remission and high recurrence rates.

In contrast, CO2 lasers have been shown to be effective treatment modalities for larger vulvar LC lesions and in patients with treatment failure after other nonsurgical treatments. CO2 lasers are hypothesized to work through vaporization of the abnormal lymphatics and by sealing off deeper lymphatic channels. While our patient has responded well thus far, she will require follow-up given focal recurrence at 1 year that has been noted.5

Ms Pouldar is with the division of dermatology at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Hisaw is with the division of dermatology at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Turegano is with the division of dermatopathology, department of pathology and laboratory medicine, at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Vardanian is with the division of plastic and reconstructive surgery, department of surgery at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Dr Young is with the division of dermatology at David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, in Los Angeles, CA.

Disclosure: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Gnanaraj P, Revathy V, Venugopal V, Tamilchelvan D, Rajagopalan V. Secondary lymphangioma of vulva: a report of two cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57(2):149-151.

2. Chang MB, Newman CC, Davis MD, Lehman JS. Acquired lymphangiectasia (lymphangioma circumscriptum) of the vulva: Clinicopathologic study of 11 patients from a single institution and 67 from the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55(9):e482-497.

3. Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Burchette JL, Foo WC, Selim MA. Acquired vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a comparison of 12 cases with Crohn’s associated lesions or radiation therapy induced tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(9):958-965.

4. Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94(5):473-486.

5. Huilgol SC, Neill S, Barlow RJ. CO(2) laser therapy of vulval lymphangiectasia and lymphangioma circumscriptum. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(7):575-577.