Diagnosis: Superficial granulomatous pyoderma (PASH syndrome)

Superficial granulomatous pyoderma (SGP) is an uncommon variant of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) that is distinguished by morphology, anatomical predilection, progression, and lack of association with underlying systemic conditions.1 Additionally, SGP has a favorable treatment response that distinguishes it from other PG subtypes. PG, acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (PASH) syndrome is a hereditary autoinflammatory disorder defined by the presence of all three conditions. SGP in the context of PASH syndrome has rarely been described, yet it poses a unique therapeutic challenge as exemplified in this case.

Etiology/Differential Diagnosis

PG is an uncommon chronic inflammatory skin disorder possibly related to an underlying immunologic abnormality.2 Although PG is idiopathic in 25% to 50% of cases, it may be associated with underlying systemic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, paraproteinemia, arthritis, and myeloproliferative disorders.2 The literature has reported several clinical variants of PG aside from the classic ulcerative form, including pustular, bullous, pyostomatitis vegentans, extracutaneous, and SGP.3,4

SGP was first described in 1988, when Wilson-Jones and Winkelmann reported the entity as separate from classic PG due to a slower progression, vegetative or crusted borders as opposed to rapidly advancing liquefying borders, a clean and granulating ulcer base, and lack of underlying gastrointestinal disease (Figure 1).2

The differential diagnosis for SGP includes infectious etiologies (deep fungal and mycobacterial infections), sarcoidosis, halogenoderma, and pemphigus vegetans.2 Ruling out infectious etiologies is imperative, as PG is a diagnosis of exclusion. Major criteria for a diagnosis of SGP include the presence of characteristic lesions and exclusion of other causes. Minor criteria include characteristic histopathology, lack of systemic associations, and rapid response to treatment with steroids. Both proposed major criteria and at least two proposed minor criteria must be met to arrive at a diagnosis of SGP.2

Histology

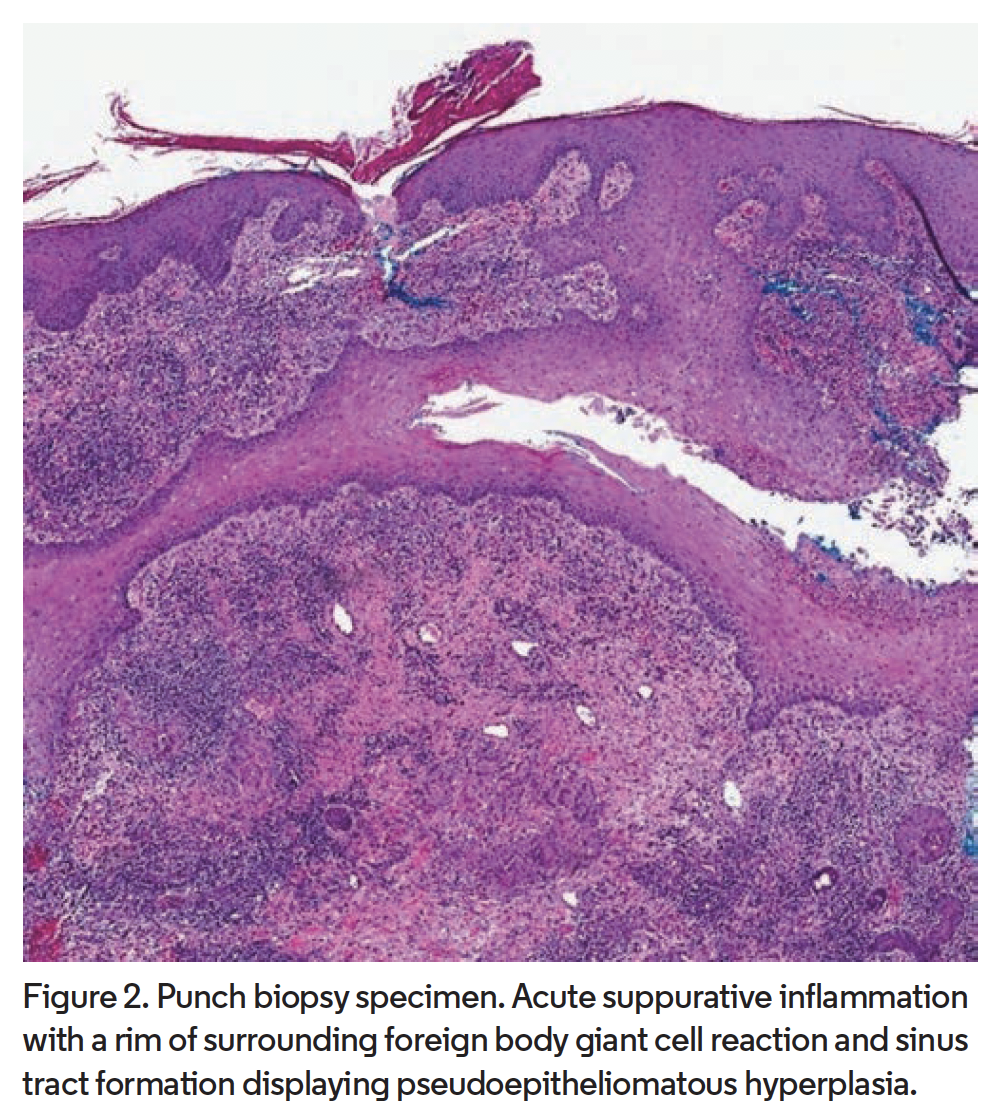

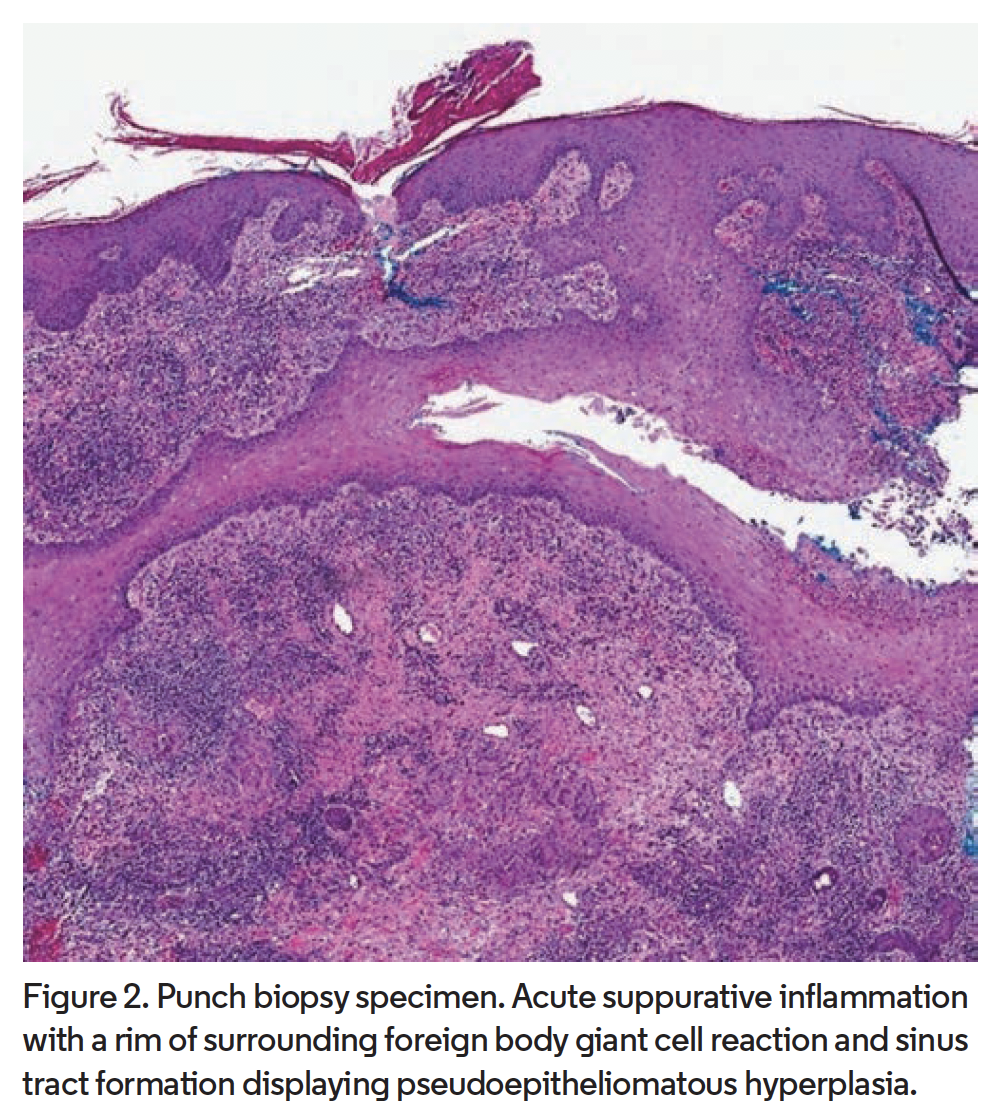

Histologically, SGP differs from classic PG due to the presence of trilayered granulomas. Granulomas in SGP are composed of a central layer of neutrophilic inflammation or abscess formation within the superficial dermis; a surrounding layer composed of giant cells, histiocytes, hemorrhage, and granulation tissue; and an outer layer of dense plasma cell infiltrate with possible eosinophils. SGP primarily extends into the upper reticular dermis without deeper infiltration. There is a notable lack of subcutaneous tissue involvement. Other histologic findings that are not specific for SGP but documented in the literature include acanthosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, sinus tract formation, and superficial dermal abscesses of neutrophils surrounded by histiocytes and giant cells.2,5

Management

SGP typically demonstrates a prompt response to conservative management as lesions may resolve spontaneously. First-line therapy, when indicated, includes topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, or systemic antibiotics.2,6

Alternatively, for PASH syndrome, oral corticosteroids, cyclosporine, anti-tumor necrosis factor agents, and IL-1 antagonists have demonstrated efficacy.1,7,8 The SGP variant of PG in association with PASH syndrome may therefore complicate clinical management.

Our Patient

Punch biopsy from the abdomen revealed sinus tract formation with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and acute suppurative inflammation with a rim of surrounding foreign body giant cell reaction (Figure 2). Beyond this, a layer of dense plasma cell rich chronic inflammation was observed. Periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver, and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as direct immunofluorescence were negative. Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated liver function tests. A colonoscopy did not reveal underlying bowel disease. These clinical and histopathologic findings in addition to negative cultures supported the diagnosis of SGP. In the presence of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) involving the groin and gluteal cleft, as well as severe acne, a diagnosis of PASH syndrome was also made.

Punch biopsy from the abdomen revealed sinus tract formation with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and acute suppurative inflammation with a rim of surrounding foreign body giant cell reaction (Figure 2). Beyond this, a layer of dense plasma cell rich chronic inflammation was observed. Periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver, and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as direct immunofluorescence were negative. Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated liver function tests. A colonoscopy did not reveal underlying bowel disease. These clinical and histopathologic findings in addition to negative cultures supported the diagnosis of SGP. In the presence of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) involving the groin and gluteal cleft, as well as severe acne, a diagnosis of PASH syndrome was also made.

The patient was treated for SGP with systemic, topical, and intralesional steroids as well as topical tacrolimus without significant improvement. Systemic steroids were discontinued after 12 weeks and oral doxycycline was initiated. While the patient experienced moderate improvement of lesions and decreased pain with doxycycline, the vegetative abdominal lesions persisted. This failure to respond may stem from the presence of SGP in the context of PASH syndrome.

Considering the failure of the vegetative abdominal lesions to respond to conservative management and the persistence of acne and HS components throughout numerous treatment regimens, along with the widely reported use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors in the management of both PG and PASH syndrome, we chose to initiate therapy with TNFα inhibitor adalimumab. After initiation of weekly 40-mg subcutaneous injection, his abdominal lesion began to improve.

Conclusion

SGP is an uncommon variant of PG historically described as having an adequate response to the conservative therapies of topical corticosteroids and systemic antibiotics. This case demonstrates the rare presentation of SGP and its failure to respond to conservative measures when in the context of PASH syndrome. Practicing dermatologists may benefit from the knowledge of a potential lack of response to standard conservative therapy for SGP when present with PASH syndrome and consider a lower threshold for starting systemic immunosuppressive therapy to treat SGP in this presentation.

Dr Buckland is a senior resident at the St. Joseph Mercy Livingston Dermatology Program in Ypsilanti, MI. Dr Sabzevari is a senior resident at the St. Joseph Mercy Livingston Dermatology Program. Dr Visconti is an intern physician at St. Joseph Mercy Ann Arbor. Dr LaFond is with the St. Joseph Mercy Livingston Dermatology Program. Dr Fivenson is with the St. Joseph Mercy Livingston Dermatology Program. Dr Ghaferi is with the St. Joseph Mercy Livingston Dermatology Program and department of pathology/dermatopathology at St. Joseph Mercy.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, Ruzicka T. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)--a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(3):409-415. doi:10.1016/

j.jaad.2010.12.025

2. Wilson-Jones E, Winkelmann RK. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma: a localized vegetative form of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(3):511-521. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70074-2

3. Bhat RM. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an update. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2012;3(1):7-13. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.93482

4. Lemos AC, Aveiro D, Santos N, Marques V, Pinheiro LF. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an uncommon case report and review of the literature. Wounds. 2017;29(9):E61-E69.

5. Hardwick N, Cerio R. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129(6):718-722. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03339.x

6. García VS, Trelles AS. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma: successful treatment with minocycline. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(9):1134-1135. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01625.x

7. Marzano AV, Ceccherini I, Gattorno M, et al. Association of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) shares genetic and cytokine profiles with other autoinflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(27):e187. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000187

8. Niv D, Ramirez JA, Fivenson DP. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (PASH) syndrome with recurrent vasculitis. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3(1):70-73. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.11.006

Punch biopsy from the abdomen revealed sinus tract formation with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and acute suppurative inflammation with a rim of surrounding foreign body giant cell reaction (Figure 2). Beyond this, a layer of dense plasma cell rich chronic inflammation was observed. Periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver, and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as direct immunofluorescence were negative. Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated liver function tests. A colonoscopy did not reveal underlying bowel disease. These clinical and histopathologic findings in addition to negative cultures supported the diagnosis of SGP. In the presence of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) involving the groin and gluteal cleft, as well as severe acne, a diagnosis of PASH syndrome was also made.

Punch biopsy from the abdomen revealed sinus tract formation with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and acute suppurative inflammation with a rim of surrounding foreign body giant cell reaction (Figure 2). Beyond this, a layer of dense plasma cell rich chronic inflammation was observed. Periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver, and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as direct immunofluorescence were negative. Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated liver function tests. A colonoscopy did not reveal underlying bowel disease. These clinical and histopathologic findings in addition to negative cultures supported the diagnosis of SGP. In the presence of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) involving the groin and gluteal cleft, as well as severe acne, a diagnosis of PASH syndrome was also made.