Diagnosis: Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a genetic disorder characterized by brittle bones, skeletal deformities, and growth retardation. OI is the most common cause of primary osteoporosis, and its incidence is between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 20,000. It is most commonly inherited in an autosomal dominant manner; however, less common subtypes are autosomal recessive and X-linked. The manifestations of OI are often caused by defects associated with type I collagen synthesis. The diagnosis is often based on clinical features, and management is multifactorial, involving physicians and caregivers of multiple specialties.

Classification

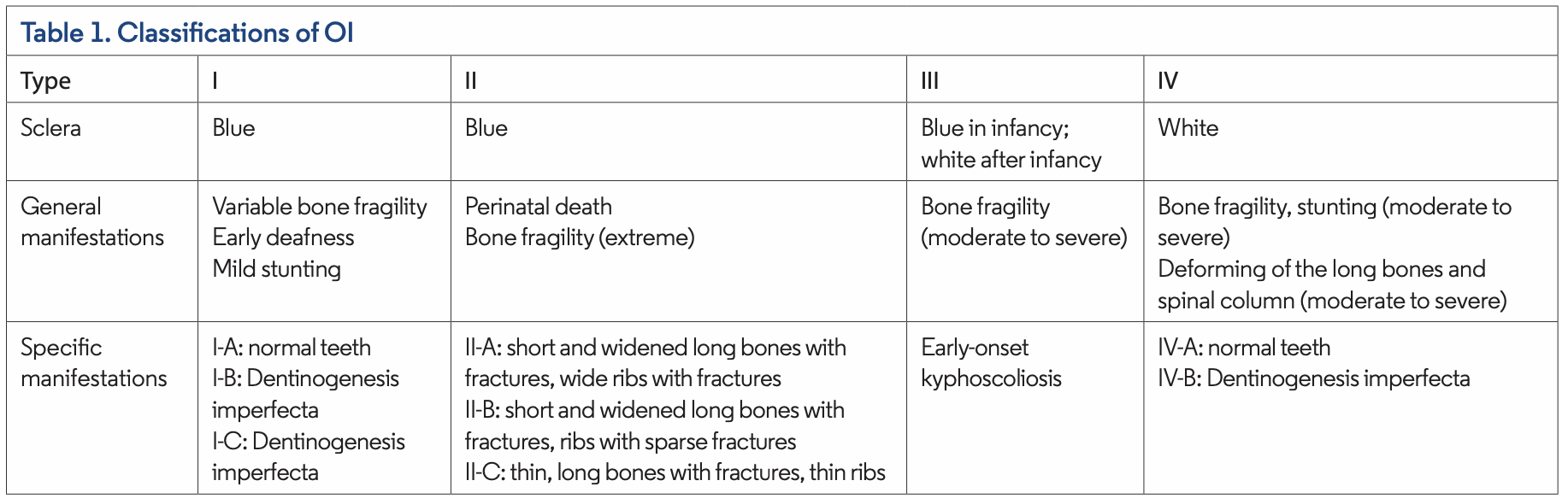

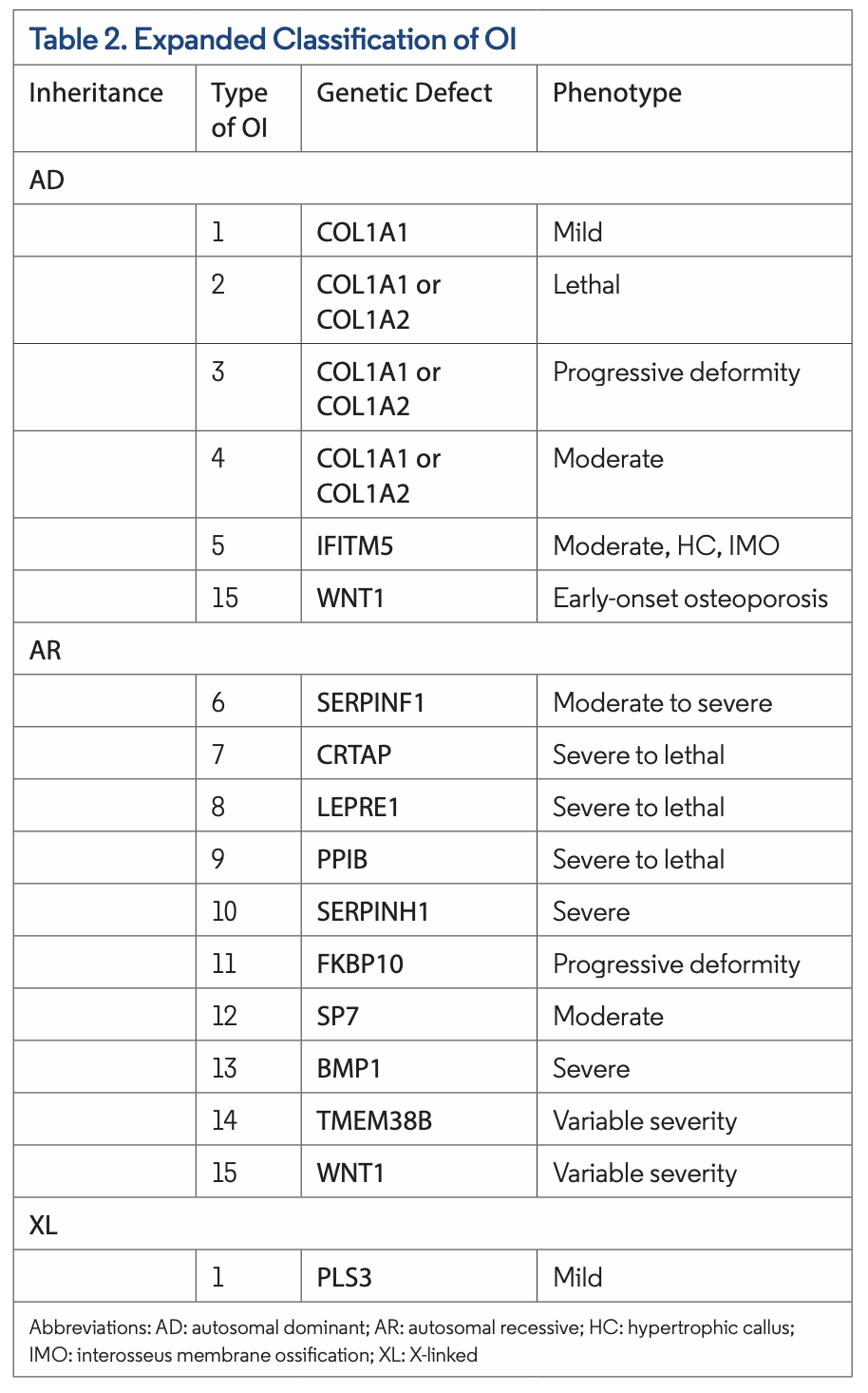

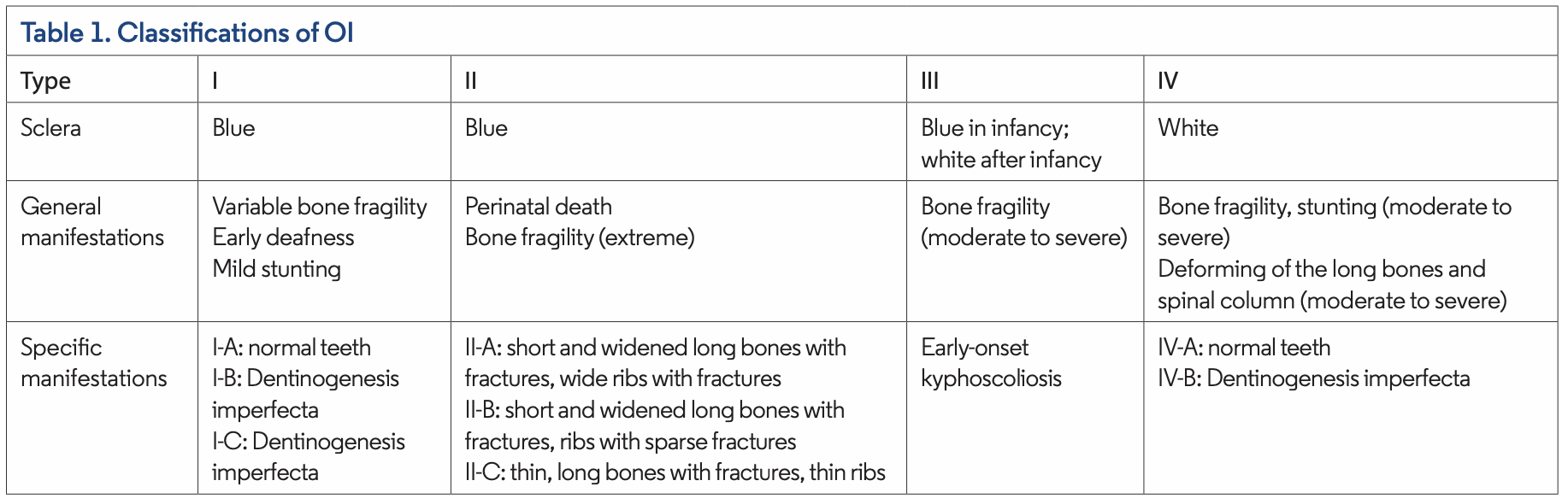

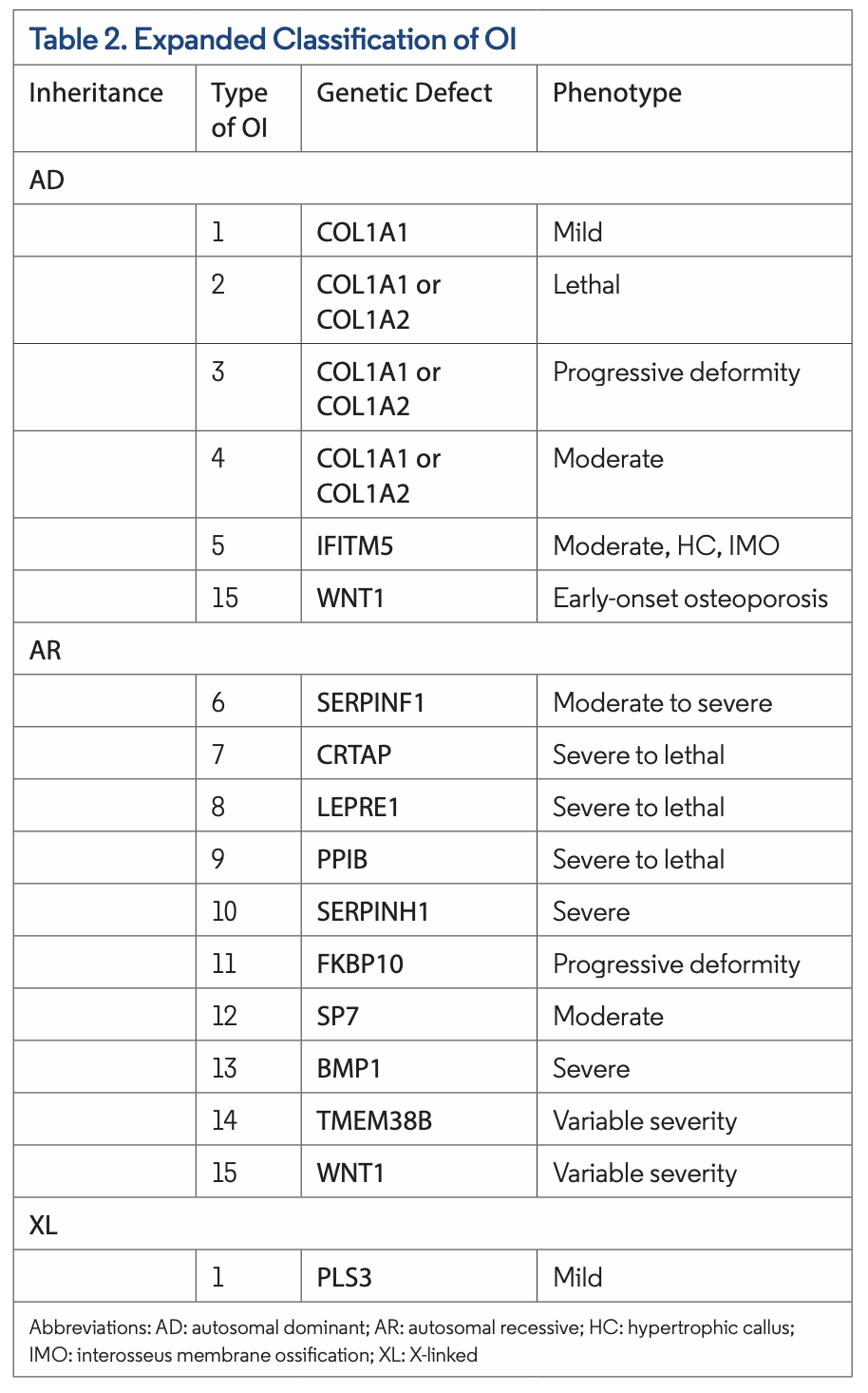

Sillence et al provided an initial classification of OI with four subtypes based on clinical and radiographic features (Table 1). More recently, with the ability to identify the molecular pathogenesis of OI, 15 subtypes of OI have been identified. Types I through V are predominantly autosomal dominant, whereas type VI through type XV are autosomal recessive. Rarely, other modes of inheritance, such as X-linked, have been identified in type I.

Type I tends to be mild, and type II is lethal around the time of childbirth or shortly after. Type III is the most severe nonlethal form, and type IV is of intermediate severity (Table 2). Type I and type IV, milder forms of OI, are more common in the population.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of OI varies based on age of onset and subtype of the disease. In the first 6 months of life, few examination findings of OI may be observed. Thereafter, the most common features are bone abnormalities, fractures, and short stature. Other common features include compression fractures, deformed craniocervical junction, hearing impairment, joint hypermobility, motor delay, osteopenia, pectus excavatum, scoliosis, teeth abnormalities (chipped teeth), and thoracic kyphosis. In addition, reduced muscle mass and strength is associated with type I, and triangular facies is associated with type III.

Similar to our patient, mucocutaneous features include blue sclera, which is often a bilateral finding (Figures 1 and 2). Blue sclerae are more common in type I OI but can also be seen in other subtypes of OI (Table 1).The blue-gray discoloration occurs due to the thin, translucent, and vascular nature of the sclera. Over time, the color of the sclera can either stay uni- form or change to a lighter blue color.

Differential Diagnosis

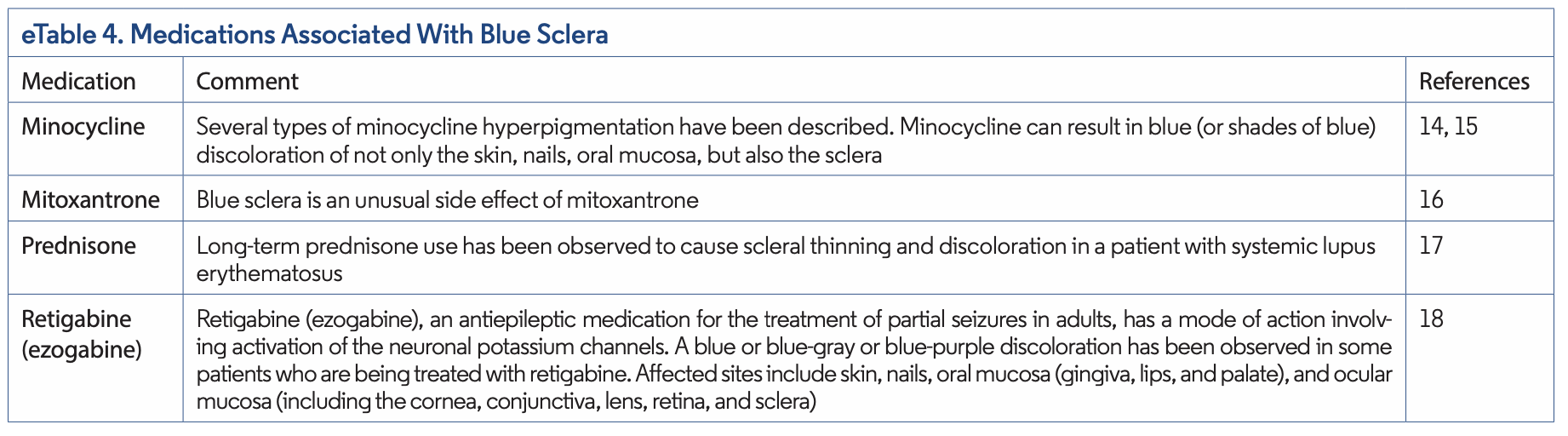

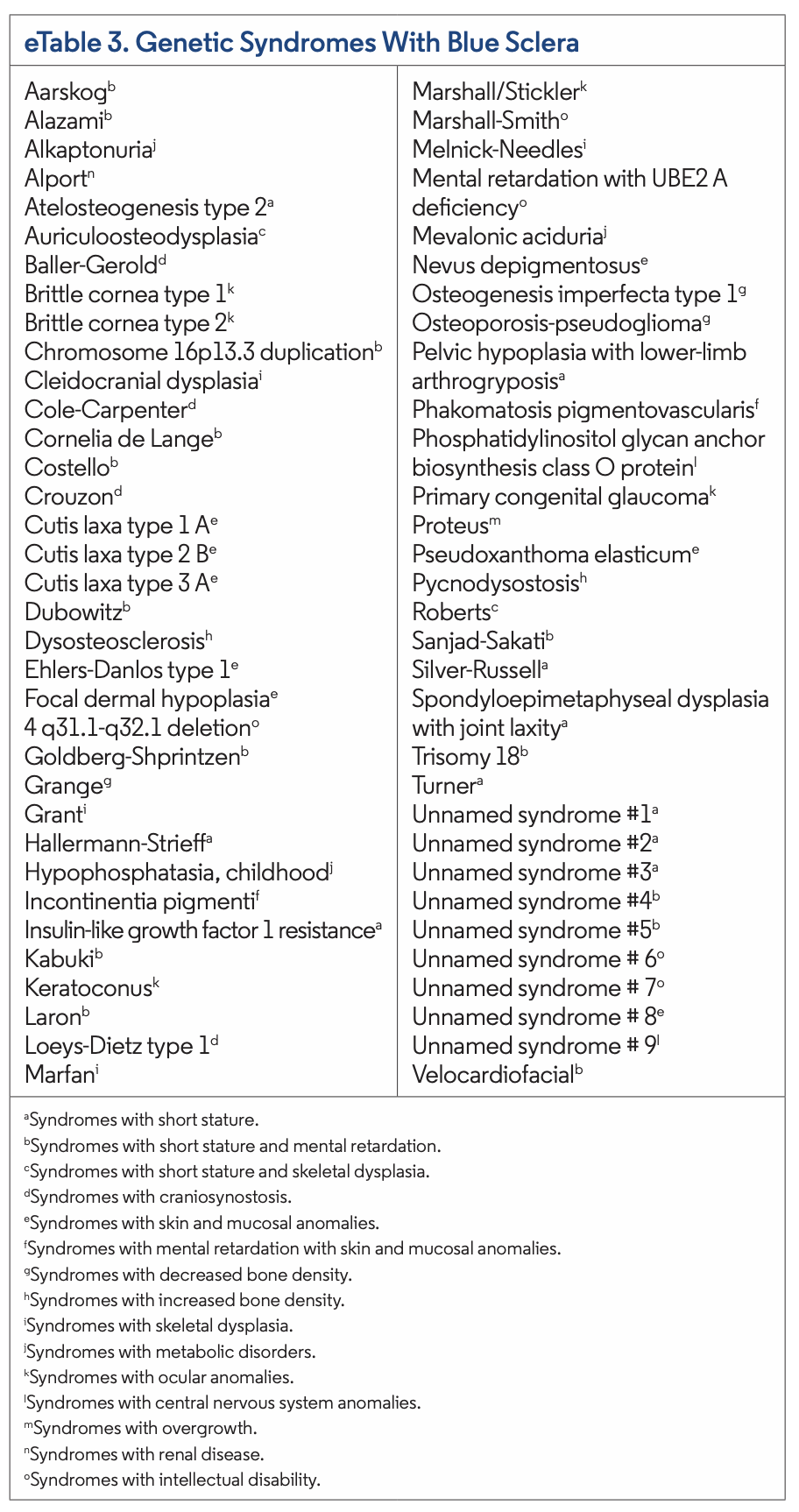

Currently, 66 genetic syndromes may present with blue sclerae and can be found in eTable 3. Nongenetic disorders and certain medications may also present with similar findings. Of the genetic syndromes, the most common to present with blue sclera include OI, Hallermann-Strieff syndrome, Kabuki syndrome, Laron syndrome, Loeys-Dietz type 1 syndrome, and Marshall-Smith syndrome. Caplan syndrome, HIV infection, hyperhomocysteinemia, iron deficiency anemia, myasthenia gravis, nevus of Ota, and acquired polyneuropathy, organo- megaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy and skin changes (POEMS) syndrome are nongenetic etiologies that may present with blue sclera. Additionally, minocycline, mitoxantrone, prednisone, and retigabine are medications that have been associated with blue sclera (eTable 4).

Sclera have also been observed that have shades of blue, either blue-black or blue-gray, in certain syndromes and systemic conditions. These include argyria, chrysiasis, Ehlers- Danlos syndrome Type VIIC, ochronosis, and OI. Nevus of Ota and dermal melanosis are pigmented lesions that can be blue-black or blue-gray, respectively.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Management

Management