Effective treatments for adults with atopic dermatitis (AD) have been available for decades, and yet clinicians and patients alike struggle with achieving adequate outcomes. Poor adherence is a critical factor limiting patients’ treatment. Even patients with extensive, lichenified AD plaques who are admitted to the hospital and started on 0.1% triamcinolone topical ointment improve rapidly over just a few days. The success of hospitalization is likely due to strict application of treatment rather than the hospital environment itself.1,2

Medication nonadherence is pervasive throughout health care, with nonadherence rates varying from 15% to 93%.3 The annual cost to the United States health care system due to nonadherence is $300 billion, which is comparable to the total gross domestic product of Denmark.4 Adherence to topical medications is dismal, with adherence rates declining to 32% over 8 weeks in AD and 51% in psoriasis.5,6 These rates were measured using electronic monitors in medication containers and were vastly different than patients’ self-reported adherence rates of greater than 90%.6 Even highly effective targeted biologic therapies often are not used optimally. Over half of patients prescribed injectable biologics do not fill their prescriptions within the first month of their appointment, and only about one quarter of those patients fill their prescription within 6 months.4

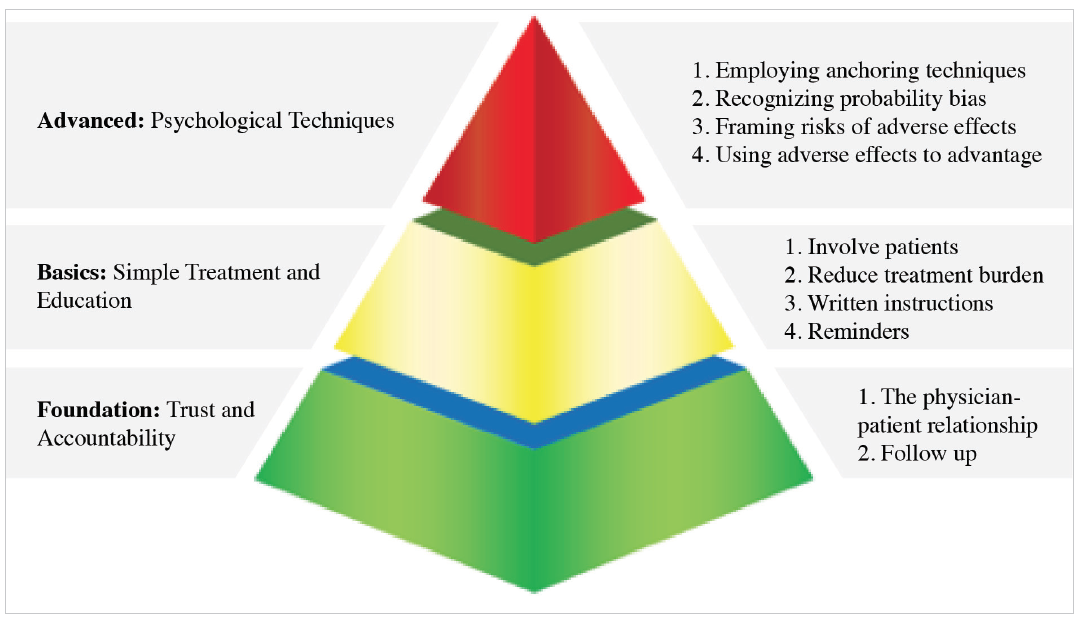

If we are dispirited about treatment failure, imagine how disheartened our patients feel. In order to provide the best care for our patients and give them the best chance at successfully managing their AD, providers need to utilize specific approaches to improve adherence and outcomes. A pyramid model can be used to describe the various approaches to patient adherence (Figure).7

Building a Foundation

A strong doctor-patient relationship is an essential component of the foundation that supports adherence. A key element that is critical to this relationship is for the patient to believe the provider is caring and friendly.8 Every part of the clinical encounter can be used to communicate caring, starting even before patients walk into the office with how staff answers patients’ phone calls. Other factors that occur before the patient sees a doctor are important as well. Is the waiting room clean, organized, and inviting? Visual cues such as a closed-off front desk, dim lighting, and outdated reading materials can convey a perceived lack of care for patients.

In addition, small changes in provider routine can impact patients’ perceptions. Entering the room slowly, establishing eye contact and greeting everyone present in the room, mentioning that you are washing your hands to protect the patient, actively listening, and incorporating touch into the clinical exam can all contribute to success.

Beyond trust and a sense of caring, accountability is underappreciated as a factor contributing to adherence. Consider this parable of 2 piano teachers: A piano teacher arranged weekly lessons for her students in preparation of their recital in 12 weeks. The night of their performance was a huge success. After the recital, another teacher saw the success and believed that it was the students’ regular practice at home, not the weekly lessons, that prepared them for the performance. He told his students that he would provide them with music to practice daily at home for their recital in 12 weeks, but that they would not need weekly lessons. The recital was miserable, as without the weekly lessons, the students did not practice.

What we do in medical practice is analogous, and likely worse, than what the second piano teacher did to his students. We supply patients with a prescription for a medication that requires them to bring it to the pharmacy, get it filled at an unknown cost, and begin taking it on their own for weeks, or even months, before we see them again to assess their response. Upon their return, if a lack of improvement is seen, we perform the same ritual again but with a different medication.

As providers, we should strive for better performance than this. Similar to the above example, studies have shown that frequent “check-ins” with patients improves adherence and outcomes.9-11 While office visits are the traditional forum for these check-ins, with the advent of sophisticated electronic health record systems, providers can utilize virtual check-ins via patient portals or other internet-based patient-provider platforms. Phone calls by nursing staff are another way to keep a consistent check-in process in place. This system is used by hospitals after a patient is discharged and has shown to decrease 30-day hospital readmission rates.12

Establishing an environment of patient-centered care and continuing that effort after the clinic visit is the foundational responsibility of the provider to improve patient adherence and outcomes.

Basic Approaches to Adherence

Getting patients involved in selecting therapies is one basic way to increase adherence.13 One patient may prioritize receiving fast results, while another patient may value limited adverse effects. The efficacy of a certain medication is irrelevant if a patient is not using it. The best vehicle for drug delivery is the one that the patient will use. Besides inquiring about patient preferences, providing samples of medications for use on a trial basis can be an outstanding way of determining the best treatment before committing to a costly medication. Furthermore, utilizing coupons and discount prescription websites can reduce the monetary burden on patients and convey that you care about the financial impact of the selected treatment regimen.

To reduce the burden of treatment, fewer prescriptions can be given. Studies have demonstrated that increasing the number of prescriptions inversely correlates with patient adherence.14,15 Simplifying treatment regimens can be achieved by having patients use a potent treatment on all areas and using it less often on areas that are more responsive to treatment instead of giving multiple prescriptions with different potency to be used on different areas. When more than 1 drug is indicated, using a combination product can reduce the complexity of treatment.

Written instructions help eliminate uncertainty on why, how, and how often medications should be used. At about 1 of 3 visits, providers do not provide enough information regarding diagnosis or treatment to allow patients to effectively recall what was discussed during the visit.16 Written instructions provide a reference for patients that can be reviewed at any time. In addition, patient portals are an excellent way to provide patients with instructions for medication use, as they can easily access this information from their phone and do not have to worry about losing a piece of paper. This reduces uncertainty as a cause for inappropriate medication use or lack of use.

Reminders to use prescriptions can be as sophisticated as setting up cell phone alarms or automated text messages, and as simple as instructing patients to put a sticky-note on the bathroom mirror or duct-taping a tube of ointment to their toothpaste. Multiple smart device applications are available to remind patients to use their medications. All of these strategies share a common goal of incorporating a new step into a patient’s daily routine. Making medication use routine can improve the likelihood of treatment adherence.

Advanced Approaches to Adherence

Psychologic techniques can encourage patients to take medications. The concept of anchoring is relevant in nearly every decision we make. It is based on how one piece of information (the anchor) will affect how we evaluate another piece of information. Anchoring is one of the key concepts used in sales because of its success.

For example, a customer sees an advertisement for a watch on sale. The watch is regularly priced at $400 but for today only it is marked down to $100. A customer would be inclined to purchase the watch and take advantage of this great deal. In another scenario, the same watch is priced at $95, but yesterday it was priced at $45. Objectively, the price of the watch in the second scenario is better compared to price in the first scenario, but due to anchoring we are more likely to choose the watch in the first scenario even though it would be more costly.

In medicine, we can tap into the concept of anchoring to help patients overcome treatment anxiety. The mention of an injectable medication may incite fear and anxiety in patients. In 2017, researchers performed a study that assessed the effects of anchoring on patients’ willingness to use injectable medications.17 Two groups of participants were divided into a control group (no anchoring question) and an intervention group (anchoring question). In the intervention group, 50 participants were asked, “How willing are you to receive a daily injection?” followed by, “How willing are you to take a monthly injection?” The control group was only asked whether they would be willing to receive a monthly injection. For many participants, their level of willingness was low. In comparisons between the control group and intervention group, however, participants who received the anchor question were 4 times more willing to receive monthly injections.

Patients with AD may express concerns regarding standard treatments due to potential adverse effects. As we educate patients regarding the relative risks of medications, we should consider framing our discussion with the awareness that patients instinctively focus on rare adverse events. Materials, such as television commercials and medication package inserts, can further fuel this preoccupation with very rare potential adverse effects. An easy way to reframe adverse effect discussions is to replace the phase “1 in 1000 patients get problem X” with the much more reassuring “999 of 1000 do not experience problem X.”

Some adverse effects can be used to our advantage to improve adherence. Several topical AD medications can result in stinging or burning, which results in treatment discontinuation. We can reframe this effect by informing the patient that the stinging is a sign the medication is working. This is true because if the patient is experiencing a benign reaction, such as stinging, it means they are using the medication and, therefore, it is working. Our patients will anchor and make judgements no matter how we present information, so presenting information in a way that will provide them the best outcomes is arguably the most ethical approach.

Using the Whole Pyramid

Although adherence is a major factor limiting AD treatment outcomes, it is not an issue that is solely the patient’s responsibility. Practitioners can and do play a role in effective adherence, and can improve outcomes by using the strategies outlined here.

The foundation of improving patient outcomes starts with building a doctor-patient relationship that nurtures honesty and accountability. Simple additional steps that can increase adherence include addressing patient concerns through effective communication and creating a simple, personalized approach to treatment. Finally, understanding some basic principles of human psychology provides a wealth of other tangible means to encourage better adherence to achieve successful outcomes.

Mr Heath is a medical student at Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine in Portland, OR.

Dr Feldman is with the Center for Dermatology Research and the Departments of Dermatology, Pathology, and Public Health Sciences at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, NC.

Disclosures: Mr Heath reports no relevant financial relationships.

Dr Feldman has received research, speaking, and consulting support from a variety of companies including Galderma, GSK/Stiefel, Almirall, Leo Pharma, Baxter, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mylan, Celgene, Pfizer, Ortho Dermatology, Taro, AbbVie, Astellas, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novan, Parion, Qurient, National Biological Corporation, and Sun Pharma. He is founder and majority owner of www.DrScore.com and founder and part owner of Causa Research, a company dedicated to enhancing patients’ adherence to treatment.

References

1. Lewis DJ, Feldman SR. Rapid, successful treatment of atopic dermatitis recalcitrant to topical corticosteroids. Pediatric Dermatol. 2018;35(2):278-279. doi:10.1111/pde.13376

2. Mudigonda T, Kaufman W, Feldman SR. Horrendous, treatment-resistant pediatric atopic dermatitis solved with a change in vehicle. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(1):114-115.

3. Balkrishnan R. The importance of medication adherence in improving chronic-disease related outcomes: what we know and what we need to further know. Med Care. 2005;43(6):517-520.

4. Harnett J, Wiederkehr D, Gerber R, Gruben D, Bourret J, Koenig A. Primary nonadherence, associated clinical outcomes, and health care resource use among patients with rheumatoid arthritis prescribed treatment with injectable biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(3):209-218. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.3.209

5. Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2):211-216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.073

6. Carroll CL, Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Manuel JC, Balkrishnan R. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial: commonly used methods of measuring adherence to topical therapy overestimate actual use. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(2):212-216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.052

7. Lewis JD, Feldman, R Steven. Practical Ways to Improve Patient Adherence. Columbia, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2017.

8. Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1(2):91-96. doi:10.2165/01312067-200801020-00004

9. Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Krejci-Manwaring J, Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R. Adherence to topical therapy increases around the time of office visits. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(1):81-83. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.005

10. Driscoll KA, Wang Y, Bennett Johnson S, et al. White coat adherence in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes who use insulin pumps. J Diabetes Sci Technology. 2016;10(3):724-729. doi:10.1177/1932296815623568

11. Davis SA, Lin HC, Yu CH, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR. Underuse of early follow-up visits: a missed opportunity to improve patients’ adherence. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(7):833-836.

12. Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(11):774-784. doi:10.7326/M14-0083

13. Abraham NS, Naik AD, Street RL Jr, et al. Complex antithrombotic therapy: determinants of patient preference and impact on medication adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1657-1668. doi:10.2147/PPA.S91553

14. Anderson KL, Dothard EH, Huang KE, Feldman SR. Frequency of primary nonadherence to acne treatment. JAMA Dermatology. 2015;151(6):623-626. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5254

15. Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Simplifying regimens promotes greater adherence and outcomes with topical acne medications: a randomized controlled trial. Cutis. 2010;86(2):103-108.

16. Storm A, Benfeldt E, Andersen SE, Andersen J. Basic drug information given by physicians is deficient, and patients’ knowledge low. J Dermatol Treat. 2009;20(4):190-193. doi:10.1080/09546630802570818

17. Oussedik E, Cardwell LA, Patel NU, Onikoyi O, Feldman SR. An anchoring-based intervention to increase patient willingness to use injectable medication in psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(9):932-934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1271

Effective treatments for adults with atopic dermatitis (AD) have been available for decades, and yet clinicians and patients alike struggle with achieving adequate outcomes. Poor adherence is a critical factor limiting patients’ treatment. Even patients with extensive, lichenified AD plaques who are admitted to the hospital and started on 0.1% triamcinolone topical ointment improve rapidly over just a few days. The success of hospitalization is likely due to strict application of treatment rather than the hospital environment itself.1,2

Medication nonadherence is pervasive throughout health care, with nonadherence rates varying from 15% to 93%.3 The annual cost to the United States health care system due to nonadherence is $300 billion, which is comparable to the total gross domestic product of Denmark.4 Adherence to topical medications is dismal, with adherence rates declining to 32% over 8 weeks in AD and 51% in psoriasis.5,6 These rates were measured using electronic monitors in medication containers and were vastly different than patients’ self-reported adherence rates of greater than 90%.6 Even highly effective targeted biologic therapies often are not used optimally. Over half of patients prescribed injectable biologics do not fill their prescriptions within the first month of their appointment, and only about one quarter of those patients fill their prescription within 6 months.4

If we are dispirited about treatment failure, imagine how disheartened our patients feel. In order to provide the best care for our patients and give them the best chance at successfully managing their AD, providers need to utilize specific approaches to improve adherence and outcomes. A pyramid model can be used to describe the various approaches to patient adherence (Figure).7

Building a Foundation

A strong doctor-patient relationship is an essential component of the foundation that supports adherence. A key element that is critical to this relationship is for the patient to believe the provider is caring and friendly.8 Every part of the clinical encounter can be used to communicate caring, starting even before patients walk into the office with how staff answers patients’ phone calls. Other factors that occur before the patient sees a doctor are important as well. Is the waiting room clean, organized, and inviting? Visual cues such as a closed-off front desk, dim lighting, and outdated reading materials can convey a perceived lack of care for patients.

In addition, small changes in provider routine can impact patients’ perceptions. Entering the room slowly, establishing eye contact and greeting everyone present in the room, mentioning that you are washing your hands to protect the patient, actively listening, and incorporating touch into the clinical exam can all contribute to success.

Beyond trust and a sense of caring, accountability is underappreciated as a factor contributing to adherence. Consider this parable of 2 piano teachers: A piano teacher arranged weekly lessons for her students in preparation of their recital in 12 weeks. The night of their performance was a huge success. After the recital, another teacher saw the success and believed that it was the students’ regular practice at home, not the weekly lessons, that prepared them for the performance. He told his students that he would provide them with music to practice daily at home for their recital in 12 weeks, but that they would not need weekly lessons. The recital was miserable, as without the weekly lessons, the students did not practice.

What we do in medical practice is analogous, and likely worse, than what the second piano teacher did to his students. We supply patients with a prescription for a medication that requires them to bring it to the pharmacy, get it filled at an unknown cost, and begin taking it on their own for weeks, or even months, before we see them again to assess their response. Upon their return, if a lack of improvement is seen, we perform the same ritual again but with a different medication.

As providers, we should strive for better performance than this. Similar to the above example, studies have shown that frequent “check-ins” with patients improves adherence and outcomes.9-11 While office visits are the traditional forum for these check-ins, with the advent of sophisticated electronic health record systems, providers can utilize virtual check-ins via patient portals or other internet-based patient-provider platforms. Phone calls by nursing staff are another way to keep a consistent check-in process in place. This system is used by hospitals after a patient is discharged and has shown to decrease 30-day hospital readmission rates.12

Establishing an environment of patient-centered care and continuing that effort after the clinic visit is the foundational responsibility of the provider to improve patient adherence and outcomes.

Basic Approaches to Adherence

Getting patients involved in selecting therapies is one basic way to increase adherence.13 One patient may prioritize receiving fast results, while another patient may value limited adverse effects. The efficacy of a certain medication is irrelevant if a patient is not using it. The best vehicle for drug delivery is the one that the patient will use. Besides inquiring about patient preferences, providing samples of medications for use on a trial basis can be an outstanding way of determining the best treatment before committing to a costly medication. Furthermore, utilizing coupons and discount prescription websites can reduce the monetary burden on patients and convey that you care about the financial impact of the selected treatment regimen.

To reduce the burden of treatment, fewer prescriptions can be given. Studies have demonstrated that increasing the number of prescriptions inversely correlates with patient adherence.14,15 Simplifying treatment regimens can be achieved by having patients use a potent treatment on all areas and using it less often on areas that are more responsive to treatment instead of giving multiple prescriptions with different potency to be used on different areas. When more than 1 drug is indicated, using a combination product can reduce the complexity of treatment.

Written instructions help eliminate uncertainty on why, how, and how often medications should be used. At about 1 of 3 visits, providers do not provide enough information regarding diagnosis or treatment to allow patients to effectively recall what was discussed during the visit.16 Written instructions provide a reference for patients that can be reviewed at any time. In addition, patient portals are an excellent way to provide patients with instructions for medication use, as they can easily access this information from their phone and do not have to worry about losing a piece of paper. This reduces uncertainty as a cause for inappropriate medication use or lack of use.

Reminders to use prescriptions can be as sophisticated as setting up cell phone alarms or automated text messages, and as simple as instructing patients to put a sticky-note on the bathroom mirror or duct-taping a tube of ointment to their toothpaste. Multiple smart device applications are available to remind patients to use their medications. All of these strategies share a common goal of incorporating a new step into a patient’s daily routine. Making medication use routine can improve the likelihood of treatment adherence.

Advanced Approaches to Adherence

Psychologic techniques can encourage patients to take medications. The concept of anchoring is relevant in nearly every decision we make. It is based on how one piece of information (the anchor) will affect how we evaluate another piece of information. Anchoring is one of the key concepts used in sales because of its success.

For example, a customer sees an advertisement for a watch on sale. The watch is regularly priced at $400 but for today only it is marked down to $100. A customer would be inclined to purchase the watch and take advantage of this great deal. In another scenario, the same watch is priced at $95, but yesterday it was priced at $45. Objectively, the price of the watch in the second scenario is better compared to price in the first scenario, but due to anchoring we are more likely to choose the watch in the first scenario even though it would be more costly.

In medicine, we can tap into the concept of anchoring to help patients overcome treatment anxiety. The mention of an injectable medication may incite fear and anxiety in patients. In 2017, researchers performed a study that assessed the effects of anchoring on patients’ willingness to use injectable medications.17 Two groups of participants were divided into a control group (no anchoring question) and an intervention group (anchoring question). In the intervention group, 50 participants were asked, “How willing are you to receive a daily injection?” followed by, “How willing are you to take a monthly injection?” The control group was only asked whether they would be willing to receive a monthly injection. For many participants, their level of willingness was low. In comparisons between the control group and intervention group, however, participants who received the anchor question were 4 times more willing to receive monthly injections.

Patients with AD may express concerns regarding standard treatments due to potential adverse effects. As we educate patients regarding the relative risks of medications, we should consider framing our discussion with the awareness that patients instinctively focus on rare adverse events. Materials, such as television commercials and medication package inserts, can further fuel this preoccupation with very rare potential adverse effects. An easy way to reframe adverse effect discussions is to replace the phase “1 in 1000 patients get problem X” with the much more reassuring “999 of 1000 do not experience problem X.”

Some adverse effects can be used to our advantage to improve adherence. Several topical AD medications can result in stinging or burning, which results in treatment discontinuation. We can reframe this effect by informing the patient that the stinging is a sign the medication is working. This is true because if the patient is experiencing a benign reaction, such as stinging, it means they are using the medication and, therefore, it is working. Our patients will anchor and make judgements no matter how we present information, so presenting information in a way that will provide them the best outcomes is arguably the most ethical approach.

Using the Whole Pyramid

Although adherence is a major factor limiting AD treatment outcomes, it is not an issue that is solely the patient’s responsibility. Practitioners can and do play a role in effective adherence, and can improve outcomes by using the strategies outlined here.

The foundation of improving patient outcomes starts with building a doctor-patient relationship that nurtures honesty and accountability. Simple additional steps that can increase adherence include addressing patient concerns through effective communication and creating a simple, personalized approach to treatment. Finally, understanding some basic principles of human psychology provides a wealth of other tangible means to encourage better adherence to achieve successful outcomes.

Mr Heath is a medical student at Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine in Portland, OR.

Dr Feldman is with the Center for Dermatology Research and the Departments of Dermatology, Pathology, and Public Health Sciences at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, NC.

Disclosures: Mr Heath reports no relevant financial relationships.

Dr Feldman has received research, speaking, and consulting support from a variety of companies including Galderma, GSK/Stiefel, Almirall, Leo Pharma, Baxter, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mylan, Celgene, Pfizer, Ortho Dermatology, Taro, AbbVie, Astellas, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novan, Parion, Qurient, National Biological Corporation, and Sun Pharma. He is founder and majority owner of www.DrScore.com and founder and part owner of Causa Research, a company dedicated to enhancing patients’ adherence to treatment.

References

1. Lewis DJ, Feldman SR. Rapid, successful treatment of atopic dermatitis recalcitrant to topical corticosteroids. Pediatric Dermatol. 2018;35(2):278-279. doi:10.1111/pde.13376

2. Mudigonda T, Kaufman W, Feldman SR. Horrendous, treatment-resistant pediatric atopic dermatitis solved with a change in vehicle. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(1):114-115.

3. Balkrishnan R. The importance of medication adherence in improving chronic-disease related outcomes: what we know and what we need to further know. Med Care. 2005;43(6):517-520.

4. Harnett J, Wiederkehr D, Gerber R, Gruben D, Bourret J, Koenig A. Primary nonadherence, associated clinical outcomes, and health care resource use among patients with rheumatoid arthritis prescribed treatment with injectable biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(3):209-218. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.3.209

5. Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2):211-216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.073

6. Carroll CL, Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Manuel JC, Balkrishnan R. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial: commonly used methods of measuring adherence to topical therapy overestimate actual use. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(2):212-216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.052

7. Lewis JD, Feldman, R Steven. Practical Ways to Improve Patient Adherence. Columbia, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2017.

8. Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1(2):91-96. doi:10.2165/01312067-200801020-00004

9. Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Krejci-Manwaring J, Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R. Adherence to topical therapy increases around the time of office visits. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(1):81-83. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.005

10. Driscoll KA, Wang Y, Bennett Johnson S, et al. White coat adherence in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes who use insulin pumps. J Diabetes Sci Technology. 2016;10(3):724-729. doi:10.1177/1932296815623568

11. Davis SA, Lin HC, Yu CH, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR. Underuse of early follow-up visits: a missed opportunity to improve patients’ adherence. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(7):833-836.

12. Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(11):774-784. doi:10.7326/M14-0083

13. Abraham NS, Naik AD, Street RL Jr, et al. Complex antithrombotic therapy: determinants of patient preference and impact on medication adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1657-1668. doi:10.2147/PPA.S91553

14. Anderson KL, Dothard EH, Huang KE, Feldman SR. Frequency of primary nonadherence to acne treatment. JAMA Dermatology. 2015;151(6):623-626. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5254

15. Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Simplifying regimens promotes greater adherence and outcomes with topical acne medications: a randomized controlled trial. Cutis. 2010;86(2):103-108.

16. Storm A, Benfeldt E, Andersen SE, Andersen J. Basic drug information given by physicians is deficient, and patients’ knowledge low. J Dermatol Treat. 2009;20(4):190-193. doi:10.1080/09546630802570818

17. Oussedik E, Cardwell LA, Patel NU, Onikoyi O, Feldman SR. An anchoring-based intervention to increase patient willingness to use injectable medication in psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(9):932-934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1271

Effective treatments for adults with atopic dermatitis (AD) have been available for decades, and yet clinicians and patients alike struggle with achieving adequate outcomes. Poor adherence is a critical factor limiting patients’ treatment. Even patients with extensive, lichenified AD plaques who are admitted to the hospital and started on 0.1% triamcinolone topical ointment improve rapidly over just a few days. The success of hospitalization is likely due to strict application of treatment rather than the hospital environment itself.1,2

Medication nonadherence is pervasive throughout health care, with nonadherence rates varying from 15% to 93%.3 The annual cost to the United States health care system due to nonadherence is $300 billion, which is comparable to the total gross domestic product of Denmark.4 Adherence to topical medications is dismal, with adherence rates declining to 32% over 8 weeks in AD and 51% in psoriasis.5,6 These rates were measured using electronic monitors in medication containers and were vastly different than patients’ self-reported adherence rates of greater than 90%.6 Even highly effective targeted biologic therapies often are not used optimally. Over half of patients prescribed injectable biologics do not fill their prescriptions within the first month of their appointment, and only about one quarter of those patients fill their prescription within 6 months.4

If we are dispirited about treatment failure, imagine how disheartened our patients feel. In order to provide the best care for our patients and give them the best chance at successfully managing their AD, providers need to utilize specific approaches to improve adherence and outcomes. A pyramid model can be used to describe the various approaches to patient adherence (Figure).7

Building a Foundation

A strong doctor-patient relationship is an essential component of the foundation that supports adherence. A key element that is critical to this relationship is for the patient to believe the provider is caring and friendly.8 Every part of the clinical encounter can be used to communicate caring, starting even before patients walk into the office with how staff answers patients’ phone calls. Other factors that occur before the patient sees a doctor are important as well. Is the waiting room clean, organized, and inviting? Visual cues such as a closed-off front desk, dim lighting, and outdated reading materials can convey a perceived lack of care for patients.

In addition, small changes in provider routine can impact patients’ perceptions. Entering the room slowly, establishing eye contact and greeting everyone present in the room, mentioning that you are washing your hands to protect the patient, actively listening, and incorporating touch into the clinical exam can all contribute to success.

Beyond trust and a sense of caring, accountability is underappreciated as a factor contributing to adherence. Consider this parable of 2 piano teachers: A piano teacher arranged weekly lessons for her students in preparation of their recital in 12 weeks. The night of their performance was a huge success. After the recital, another teacher saw the success and believed that it was the students’ regular practice at home, not the weekly lessons, that prepared them for the performance. He told his students that he would provide them with music to practice daily at home for their recital in 12 weeks, but that they would not need weekly lessons. The recital was miserable, as without the weekly lessons, the students did not practice.

What we do in medical practice is analogous, and likely worse, than what the second piano teacher did to his students. We supply patients with a prescription for a medication that requires them to bring it to the pharmacy, get it filled at an unknown cost, and begin taking it on their own for weeks, or even months, before we see them again to assess their response. Upon their return, if a lack of improvement is seen, we perform the same ritual again but with a different medication.

As providers, we should strive for better performance than this. Similar to the above example, studies have shown that frequent “check-ins” with patients improves adherence and outcomes.9-11 While office visits are the traditional forum for these check-ins, with the advent of sophisticated electronic health record systems, providers can utilize virtual check-ins via patient portals or other internet-based patient-provider platforms. Phone calls by nursing staff are another way to keep a consistent check-in process in place. This system is used by hospitals after a patient is discharged and has shown to decrease 30-day hospital readmission rates.12

Establishing an environment of patient-centered care and continuing that effort after the clinic visit is the foundational responsibility of the provider to improve patient adherence and outcomes.

Basic Approaches to Adherence

Getting patients involved in selecting therapies is one basic way to increase adherence.13 One patient may prioritize receiving fast results, while another patient may value limited adverse effects. The efficacy of a certain medication is irrelevant if a patient is not using it. The best vehicle for drug delivery is the one that the patient will use. Besides inquiring about patient preferences, providing samples of medications for use on a trial basis can be an outstanding way of determining the best treatment before committing to a costly medication. Furthermore, utilizing coupons and discount prescription websites can reduce the monetary burden on patients and convey that you care about the financial impact of the selected treatment regimen.

To reduce the burden of treatment, fewer prescriptions can be given. Studies have demonstrated that increasing the number of prescriptions inversely correlates with patient adherence.14,15 Simplifying treatment regimens can be achieved by having patients use a potent treatment on all areas and using it less often on areas that are more responsive to treatment instead of giving multiple prescriptions with different potency to be used on different areas. When more than 1 drug is indicated, using a combination product can reduce the complexity of treatment.

Written instructions help eliminate uncertainty on why, how, and how often medications should be used. At about 1 of 3 visits, providers do not provide enough information regarding diagnosis or treatment to allow patients to effectively recall what was discussed during the visit.16 Written instructions provide a reference for patients that can be reviewed at any time. In addition, patient portals are an excellent way to provide patients with instructions for medication use, as they can easily access this information from their phone and do not have to worry about losing a piece of paper. This reduces uncertainty as a cause for inappropriate medication use or lack of use.

Reminders to use prescriptions can be as sophisticated as setting up cell phone alarms or automated text messages, and as simple as instructing patients to put a sticky-note on the bathroom mirror or duct-taping a tube of ointment to their toothpaste. Multiple smart device applications are available to remind patients to use their medications. All of these strategies share a common goal of incorporating a new step into a patient’s daily routine. Making medication use routine can improve the likelihood of treatment adherence.

Advanced Approaches to Adherence

Psychologic techniques can encourage patients to take medications. The concept of anchoring is relevant in nearly every decision we make. It is based on how one piece of information (the anchor) will affect how we evaluate another piece of information. Anchoring is one of the key concepts used in sales because of its success.

For example, a customer sees an advertisement for a watch on sale. The watch is regularly priced at $400 but for today only it is marked down to $100. A customer would be inclined to purchase the watch and take advantage of this great deal. In another scenario, the same watch is priced at $95, but yesterday it was priced at $45. Objectively, the price of the watch in the second scenario is better compared to price in the first scenario, but due to anchoring we are more likely to choose the watch in the first scenario even though it would be more costly.

In medicine, we can tap into the concept of anchoring to help patients overcome treatment anxiety. The mention of an injectable medication may incite fear and anxiety in patients. In 2017, researchers performed a study that assessed the effects of anchoring on patients’ willingness to use injectable medications.17 Two groups of participants were divided into a control group (no anchoring question) and an intervention group (anchoring question). In the intervention group, 50 participants were asked, “How willing are you to receive a daily injection?” followed by, “How willing are you to take a monthly injection?” The control group was only asked whether they would be willing to receive a monthly injection. For many participants, their level of willingness was low. In comparisons between the control group and intervention group, however, participants who received the anchor question were 4 times more willing to receive monthly injections.

Patients with AD may express concerns regarding standard treatments due to potential adverse effects. As we educate patients regarding the relative risks of medications, we should consider framing our discussion with the awareness that patients instinctively focus on rare adverse events. Materials, such as television commercials and medication package inserts, can further fuel this preoccupation with very rare potential adverse effects. An easy way to reframe adverse effect discussions is to replace the phase “1 in 1000 patients get problem X” with the much more reassuring “999 of 1000 do not experience problem X.”

Some adverse effects can be used to our advantage to improve adherence. Several topical AD medications can result in stinging or burning, which results in treatment discontinuation. We can reframe this effect by informing the patient that the stinging is a sign the medication is working. This is true because if the patient is experiencing a benign reaction, such as stinging, it means they are using the medication and, therefore, it is working. Our patients will anchor and make judgements no matter how we present information, so presenting information in a way that will provide them the best outcomes is arguably the most ethical approach.

Using the Whole Pyramid

Although adherence is a major factor limiting AD treatment outcomes, it is not an issue that is solely the patient’s responsibility. Practitioners can and do play a role in effective adherence, and can improve outcomes by using the strategies outlined here.

The foundation of improving patient outcomes starts with building a doctor-patient relationship that nurtures honesty and accountability. Simple additional steps that can increase adherence include addressing patient concerns through effective communication and creating a simple, personalized approach to treatment. Finally, understanding some basic principles of human psychology provides a wealth of other tangible means to encourage better adherence to achieve successful outcomes.

Mr Heath is a medical student at Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine in Portland, OR.

Dr Feldman is with the Center for Dermatology Research and the Departments of Dermatology, Pathology, and Public Health Sciences at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, NC.

Disclosures: Mr Heath reports no relevant financial relationships.

Dr Feldman has received research, speaking, and consulting support from a variety of companies including Galderma, GSK/Stiefel, Almirall, Leo Pharma, Baxter, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mylan, Celgene, Pfizer, Ortho Dermatology, Taro, AbbVie, Astellas, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novan, Parion, Qurient, National Biological Corporation, and Sun Pharma. He is founder and majority owner of www.DrScore.com and founder and part owner of Causa Research, a company dedicated to enhancing patients’ adherence to treatment.

References

1. Lewis DJ, Feldman SR. Rapid, successful treatment of atopic dermatitis recalcitrant to topical corticosteroids. Pediatric Dermatol. 2018;35(2):278-279. doi:10.1111/pde.13376

2. Mudigonda T, Kaufman W, Feldman SR. Horrendous, treatment-resistant pediatric atopic dermatitis solved with a change in vehicle. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(1):114-115.

3. Balkrishnan R. The importance of medication adherence in improving chronic-disease related outcomes: what we know and what we need to further know. Med Care. 2005;43(6):517-520.

4. Harnett J, Wiederkehr D, Gerber R, Gruben D, Bourret J, Koenig A. Primary nonadherence, associated clinical outcomes, and health care resource use among patients with rheumatoid arthritis prescribed treatment with injectable biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(3):209-218. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.3.209

5. Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2):211-216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.073

6. Carroll CL, Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Manuel JC, Balkrishnan R. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial: commonly used methods of measuring adherence to topical therapy overestimate actual use. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(2):212-216. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.052

7. Lewis JD, Feldman, R Steven. Practical Ways to Improve Patient Adherence. Columbia, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2017.

8. Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1(2):91-96. doi:10.2165/01312067-200801020-00004

9. Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Krejci-Manwaring J, Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R. Adherence to topical therapy increases around the time of office visits. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(1):81-83. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.005

10. Driscoll KA, Wang Y, Bennett Johnson S, et al. White coat adherence in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes who use insulin pumps. J Diabetes Sci Technology. 2016;10(3):724-729. doi:10.1177/1932296815623568

11. Davis SA, Lin HC, Yu CH, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR. Underuse of early follow-up visits: a missed opportunity to improve patients’ adherence. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(7):833-836.

12. Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(11):774-784. doi:10.7326/M14-0083

13. Abraham NS, Naik AD, Street RL Jr, et al. Complex antithrombotic therapy: determinants of patient preference and impact on medication adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1657-1668. doi:10.2147/PPA.S91553

14. Anderson KL, Dothard EH, Huang KE, Feldman SR. Frequency of primary nonadherence to acne treatment. JAMA Dermatology. 2015;151(6):623-626. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5254

15. Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Simplifying regimens promotes greater adherence and outcomes with topical acne medications: a randomized controlled trial. Cutis. 2010;86(2):103-108.

16. Storm A, Benfeldt E, Andersen SE, Andersen J. Basic drug information given by physicians is deficient, and patients’ knowledge low. J Dermatol Treat. 2009;20(4):190-193. doi:10.1080/09546630802570818

17. Oussedik E, Cardwell LA, Patel NU, Onikoyi O, Feldman SR. An anchoring-based intervention to increase patient willingness to use injectable medication in psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(9):932-934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1271