Oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) is a rare genetic disorder that all physicians learn about in medical school, but it may never again cross your mind as a practicing dermatologist in the United States. However, in developing countries, particularly across Africa, being born with OCA makes you vulnerable to serious physical and psychosocial consequences, and even human rights violations. In an increasingly connected world, it is important to understand how skin conditions can affect patients worldwide and to learn what interventions can improve quality of life (QoL).

We present a brief overview of OCA and describe the efforts that a US dermatologist initiated to improve care for people living with albinism (PWA) in Botswana.

Clinical Features and Management

OCA is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a defect in the melanin production pathway, leading to various levels of hypopigmentation in the skin, hair, and eyes.1,2 OCA has an estimated worldwide incidence of 1 in 17,000 births, but rates as high as 1 in 1000 births are reported in certain parts of Africa, and up to 1 in 70 people worldwide may carry a gene for this condition.1-3 There are 7 recognized clinical subtypes of OCA with variable amounts of depigmentation determined by the specific genetic defect involved, and most patients have mutations in either the TYR, OCA2, TYRP1, or SLC45A2 loci.1,2 Because melanin-producing cells are crucial for development of the visual pathway, all PWA have some level of visual dysfunction such as congenital nystagmus, strabismus, photophobia, foveal hypoplasia, and reduced visual acuity in the range of 20/60 to 20/400, rendering many legally blind.1,2 OCA is diagnosed clinically based on recognition of the characteristic visual defects in association with reduced skin/hair/eye pigmentation.1-3

Because melanin absorbs UV light, the main health risk to PWA is increased susceptibility to photodamage and early onset skin cancers.4,5 Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer seen in OCA, with a reported 1000-times greater risk in PWA in Africa compared with the general population.2-6

In developing countries, PWA face greater risks of morbidity and mortality from treatable skin cancers due to limited access to health care.2-5 Additionally, lack of access to appropriate eye care leaves many PWA to needlessly go through life functionally disabled with blindness.3 Therefore, management for OCA takes a preventive approach, including sun protection practices and frequent skin checks, to reduce the risk of sun damage and subsequent skin cancers. For eye health, glasses and sun-protective eyewear are critical, and management should include a full ophthalmologic exam as early as possible to diagnose potentially treatable visual defects.

Psychosocial impact. In Africa, being visibly white among a society of predominantly dark skin creates challenges of inequality. Pervasive myths and superstitions attached to OCA in African culture include fear of contagion or bad luck, a belief that sexual intercourse with PWA cures HIV/AIDS, and the belief that the body parts of PWA can bring good fortune in rituals by traditional healers.3,7,8 These myths fuel stigma and discrimination, which prevent PWA from being accepted by society and even among their own family. Low QoL with feelings of shame, depression, and helplessness can often be the result. Alarmingly, persecution, rape, ritualized murder, and selling of the body parts of PWA have become frequent occurrences across central and southern Africa.3,7,8 The United Nations Human Rights Council has recognized the significance of this human rights issue in a call to action, mandating that nations adopt protective and supportive measures for this special population.9

Psychosocial impact. In Africa, being visibly white among a society of predominantly dark skin creates challenges of inequality. Pervasive myths and superstitions attached to OCA in African culture include fear of contagion or bad luck, a belief that sexual intercourse with PWA cures HIV/AIDS, and the belief that the body parts of PWA can bring good fortune in rituals by traditional healers.3,7,8 These myths fuel stigma and discrimination, which prevent PWA from being accepted by society and even among their own family. Low QoL with feelings of shame, depression, and helplessness can often be the result. Alarmingly, persecution, rape, ritualized murder, and selling of the body parts of PWA have become frequent occurrences across central and southern Africa.3,7,8 The United Nations Human Rights Council has recognized the significance of this human rights issue in a call to action, mandating that nations adopt protective and supportive measures for this special population.9

Developing an Albinism Care Program

In Botswana, a developing country in sub-Saharan Africa with one of the world’s highest HIV/AIDS burdens,10 OCA is still a neglected issue. There are no established disability laws to guarantee PWA equal rights and protection from stigma and discrimination. The government funds a public health care system,11 but patients still face difficulties due to hospitals that are overburdened, undersupplied, and understaffed.

In 2016, Dr Victoria Williams started working full time as the only dermatology specialist for the Ministry of Health (MOH) of Botswana through the Botswana-University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) Partnership. As Head of Dermatology at Princess Marina Hospital (PMH), the only dermatology clinic in the public health care system at that time, Dr Williams noticed there was little community awareness about OCA. PWA, mostly from rural areas with low health care access, would present to clinic with severe sun damage and advanced skin tumors, leading to disfigurement and even death. Most disturbingly, patients had little understanding of their condition or their health care needs. Critical knowledge on the need to get skin checks, eye exams, signs of skin cancer, and how to protect themselves from the sun were lacking. Further, poor vision made it difficult for them to become educated, get a job, or be meaningfully included within society. With the aim to improve the health and QoL of PWA, Dr Williams developed the first albinism support programs in Botswana during her 2 years working as a dermatologist in the country.

Clinical care interventions. The first priority was obtaining equipment to allow early treatment of  premalignant and malignant skin lesions: cryotherapy spray cannisters, a liquid nitrogen dewar storage container, curettes, and an electrodessicator. More importantly, a workflow for sustainable access to liquid nitrogen and equipment sterilization was established within the hospital system.

premalignant and malignant skin lesions: cryotherapy spray cannisters, a liquid nitrogen dewar storage container, curettes, and an electrodessicator. More importantly, a workflow for sustainable access to liquid nitrogen and equipment sterilization was established within the hospital system.

Two clinic days per month were dedicated to OCA in order to streamline supplies and preparation for procedural treatment of skin cancers, allow patients to be seen on a walk-in basis, and sensitize hospital staff to prioritize the needs of this population. PWA were given priority to be evaluated and dispensed prescriptions in the morning, to protect them from the dangerous UV exposure of the midday sun.

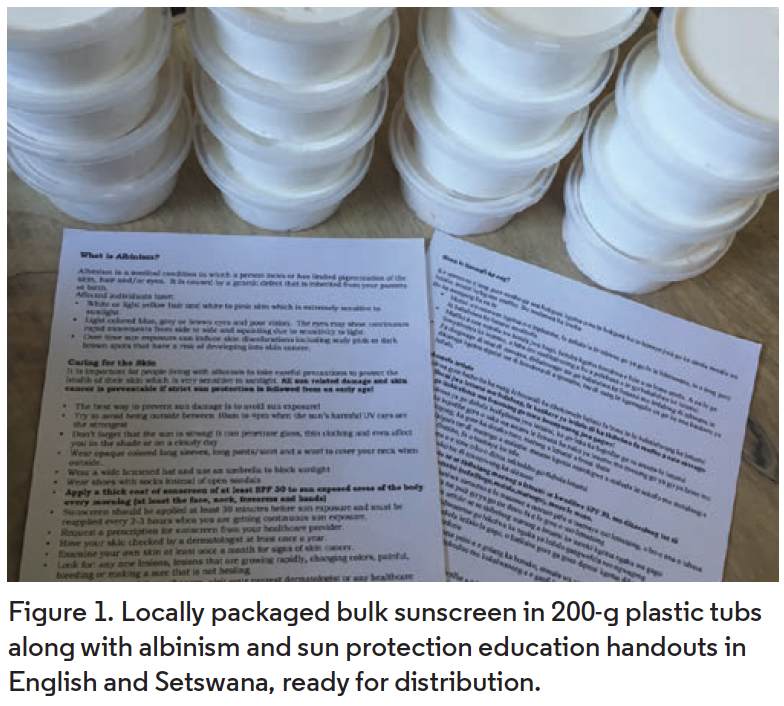

Sunscreen program. The next priority was to address sun damage prevention. Dr Williams obtained a Skincare in Developing Countries Grant from the American Academy of Dermatology to support the development of a sunscreen distribution program. After extensive research, it was determined that purchasing wholesale bulk sunscreen from South Africa and packaging it locally would be the most cost-effective and sustainable method. Thus, Dr Williams began personally packaging 200-g tubs and dispensing them to patients during skin checks. A log was created to track the demographics of PWA receiving sunscreen from the dermatology clinic in order to begin collecting the first epidemiological data on OCA in Botswana.

To ensure sustainability of the program, Dr Williams obtained support from a local nongovernmental organization, the Lady Khama Charitable Trust, to continue funding bulk sunscreen purchase. Currently, the packaging and distribution of sunscreen is transitioning to the pharmacy department at PMH to improve patient access and sustainability.

Education and awareness. After establishing improved clinical care systems, the focus shifted to patient and community perceptions. To provide key education to patients about their disease, focused handouts were created to explain OCA health needs and sun protection advice in the local language. These were provided to patients along with counseling during their skin checks (Figure 1).

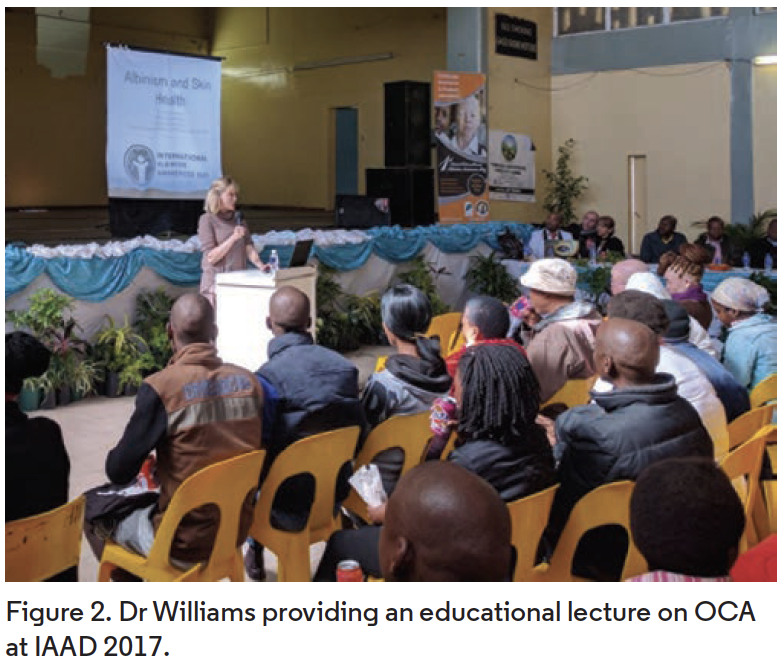

However, cultural change was needed. To improve awareness on a large scale, Dr Williams worked with local albinism organizations to pioneer the first local celebration of International Albinism Awareness Day (IAAD) on June 14, 2016, which has continued annually. Events have consisted of educational lectures about the associated skin/eye health, psychosocial, and educational needs of OCA (Figure 2); a fashion show modeling sun protection by PWA; skin and eye screenings; and a sun protection booth to distribute and counsel on the use of sunscreen, hats, sunglasses, and umbrellas (Figure 3).

However, cultural change was needed. To improve awareness on a large scale, Dr Williams worked with local albinism organizations to pioneer the first local celebration of International Albinism Awareness Day (IAAD) on June 14, 2016, which has continued annually. Events have consisted of educational lectures about the associated skin/eye health, psychosocial, and educational needs of OCA (Figure 2); a fashion show modeling sun protection by PWA; skin and eye screenings; and a sun protection booth to distribute and counsel on the use of sunscreen, hats, sunglasses, and umbrellas (Figure 3).