The contents of these questions are taken from the Galderma Pre-Board Webinar. The Pre-Board Webinar is now an online course. For details, go to www.pre-board.com. The program will be available from April 15, 2016 to November 15, 2016.

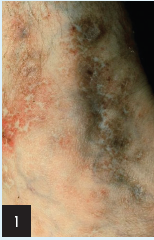

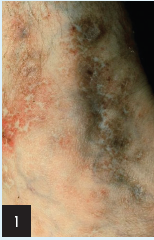

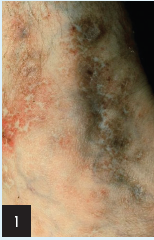

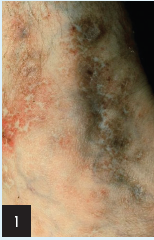

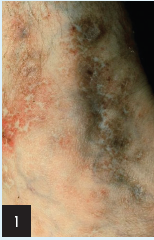

1. These ankle lesions suggest:

a) Necrobiosis lipoidica

b) Morphea

c) Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

d) Livedo reticularis

e) Livedoid vasculitis, atrophie blanche

2. Histology of these lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis would most likely show:

a) Granulomatous inflammation

b) Lobular panniculitis

c) Necrotizing vasculitis

d) Septal panniculitis

e) Thrombophlebitis

3. The diagnosis is:

a) Bullous pemphigoid

b) Pemphigus vulgaris

c) Pemphigus foliaceus

d) Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

e) Toxic epidermal necrolysis

To learn the answers, go to page 2

{{pagebreak}}

Answers

1. These ankle lesions suggest:

e) Livedoid vasculitis, atrophie blanche

Livedoid vasculitis, also known as segmental hyalinizing vasculitis, is a condition involving lower extremities, such as the lateral ankles. The condition is characterized by livedoid purpura, telangiectasia, and hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation. Atrophy producing “ivory white” scarring is also characteristic, in addition to ankle edema, bluish nodules, and ulcerations.

Histology has shown superficial, mid and deep vascular involvement with thickening and hyalinization and a relatively sparse inflammatory infiltrate. Immunoglobulin and complement components have been seen in vessel walls. An association with decreased blood fibrinolytic activity has led to the use of agents that inhibit clotting or promote fibrinolysis. The cause of livedoid vasculitis is unknown.

References

Schroeter AL, Diaz-Perez JL, Winkelmann RK, Jordan RE. Livedo vasculitis (the vasculitis of atrophie blanche). Immunohistopathologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111(2):188-193.

Shornick JK, Nicholes BK, Bergstresser PR, Gilliam JN. Idiopathic atrophie blanche. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8(6):792-798.

Heller I, Isakov A, Topilsky M. American College of Rheumatology Criteria for the diagnosis of vasculitis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(10):861.

Jayne D. Evidence-based treatment of systemic vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(6):585-595.

Gross WL, Trabandt A, Reinhold-Keller E. Diagnosis and evaluation of vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(3):245-252.

2. Histology of these lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis would most likely show:

d) Septal panniculitis

Erythema nodosum are tender lesions that arise on the extensor lower legs and dorsal feet of a patient with sarcoidosis until proven otherwise. Additionally, erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can occur as an isolated or idiopathic event, which may be associated with systematic diseases (Behçet syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, streptococcal, mycobacterial, deep fungal, and protozoan disease). In addition, it can be caused by drugs such as sulfonamides, penicillin, and BCP. Other causes of septal panniculitis can be scleroderma, necrotizing vasculitis, eosinophilic facitis, and thrombophlebitis.

Reference

Histopathology of the Skin, 1st ed. Ackerman (ed.), pp. 782-793.

3. The diagnosis is:

b) Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease characterized by flaccid blisters, erosions, and Nikolsky-positive skin. Epitheilial fragility is indicated by irregular configuration of many of the blisters, as well as the presence of overlying fragments of epidermis. No scars or millia are present.

References

Fitzpatrick TB. Dermatology in General Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1993:606-615.

Nishikawa T, Hashimoto T, Shimizu H, Ebihara T, Amagai M. Pemphigus: from immunofluorescence to molecular biology. J Dermatol Sci. 1996;12(1):1-9.

Amagai M. Autoimmunity against desmosomal cadherins in pemphigus. J Dermatol Sci. 1999;20(2):92-102.

Stanley JR. Pathophysiology and therapy of pemphigus in the 21st century. J Dermatol. 2001;28(11):645-646.

Tóth GG, Jonkman MF. Therapy of pemphigus. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(6):761-767.

The contents of these questions are taken from the Galderma Pre-Board Webinar. The Pre-Board Webinar is now an online course. For details, go to www.pre-board.com. The program will be available from April 15, 2016 to November 15, 2016.

1. These ankle lesions suggest:

a) Necrobiosis lipoidica

b) Morphea

c) Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

d) Livedo reticularis

e) Livedoid vasculitis, atrophie blanche

2. Histology of these lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis would most likely show:

a) Granulomatous inflammation

b) Lobular panniculitis

c) Necrotizing vasculitis

d) Septal panniculitis

e) Thrombophlebitis

3. The diagnosis is:

a) Bullous pemphigoid

b) Pemphigus vulgaris

c) Pemphigus foliaceus

d) Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

e) Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Answers

1. These ankle lesions suggest:

e) Livedoid vasculitis, atrophie blanche

Livedoid vasculitis, also known as segmental hyalinizing vasculitis, is a condition involving lower extremities, such as the lateral ankles. The condition is characterized by livedoid purpura, telangiectasia, and hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation. Atrophy producing “ivory white” scarring is also characteristic, in addition to ankle edema, bluish nodules, and ulcerations.

Histology has shown superficial, mid and deep vascular involvement with thickening and hyalinization and a relatively sparse inflammatory infiltrate. Immunoglobulin and complement components have been seen in vessel walls. An association with decreased blood fibrinolytic activity has led to the use of agents that inhibit clotting or promote fibrinolysis. The cause of livedoid vasculitis is unknown.

References

Schroeter AL, Diaz-Perez JL, Winkelmann RK, Jordan RE. Livedo vasculitis (the vasculitis of atrophie blanche). Immunohistopathologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111(2):188-193.

Shornick JK, Nicholes BK, Bergstresser PR, Gilliam JN. Idiopathic atrophie blanche. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8(6):792-798.

Heller I, Isakov A, Topilsky M. American College of Rheumatology Criteria for the diagnosis of vasculitis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(10):861.

Jayne D. Evidence-based treatment of systemic vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(6):585-595.

Gross WL, Trabandt A, Reinhold-Keller E. Diagnosis and evaluation of vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(3):245-252.

2. Histology of these lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis would most likely show:

d) Septal panniculitis

Erythema nodosum are tender lesions that arise on the extensor lower legs and dorsal feet of a patient with sarcoidosis until proven otherwise. Additionally, erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can occur as an isolated or idiopathic event, which may be associated with systematic diseases (Behçet syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, streptococcal, mycobacterial, deep fungal, and protozoan disease). In addition, it can be caused by drugs such as sulfonamides, penicillin, and BCP. Other causes of septal panniculitis can be scleroderma, necrotizing vasculitis, eosinophilic facitis, and thrombophlebitis.

Reference

Histopathology of the Skin, 1st ed. Ackerman (ed.), pp. 782-793.

3. The diagnosis is:

b) Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease characterized by flaccid blisters, erosions, and Nikolsky-positive skin. Epitheilial fragility is indicated by irregular configuration of many of the blisters, as well as the presence of overlying fragments of epidermis. No scars or millia are present.

References

Fitzpatrick TB. Dermatology in General Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1993:606-615.

Nishikawa T, Hashimoto T, Shimizu H, Ebihara T, Amagai M. Pemphigus: from immunofluorescence to molecular biology. J Dermatol Sci. 1996;12(1):1-9.

Amagai M. Autoimmunity against desmosomal cadherins in pemphigus. J Dermatol Sci. 1999;20(2):92-102.

Stanley JR. Pathophysiology and therapy of pemphigus in the 21st century. J Dermatol. 2001;28(11):645-646.

Tóth GG, Jonkman MF. Therapy of pemphigus. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(6):761-767.

The contents of these questions are taken from the Galderma Pre-Board Webinar. The Pre-Board Webinar is now an online course. For details, go to www.pre-board.com. The program will be available from April 15, 2016 to November 15, 2016.

1. These ankle lesions suggest:

a) Necrobiosis lipoidica

b) Morphea

c) Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

d) Livedo reticularis

e) Livedoid vasculitis, atrophie blanche

2. Histology of these lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis would most likely show:

a) Granulomatous inflammation

b) Lobular panniculitis

c) Necrotizing vasculitis

d) Septal panniculitis

e) Thrombophlebitis

3. The diagnosis is:

a) Bullous pemphigoid

b) Pemphigus vulgaris

c) Pemphigus foliaceus

d) Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

e) Toxic epidermal necrolysis

,

The contents of these questions are taken from the Galderma Pre-Board Webinar. The Pre-Board Webinar is now an online course. For details, go to www.pre-board.com. The program will be available from April 15, 2016 to November 15, 2016.

1. These ankle lesions suggest:

a) Necrobiosis lipoidica

b) Morphea

c) Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

d) Livedo reticularis

e) Livedoid vasculitis, atrophie blanche

2. Histology of these lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis would most likely show:

a) Granulomatous inflammation

b) Lobular panniculitis

c) Necrotizing vasculitis

d) Septal panniculitis

e) Thrombophlebitis

3. The diagnosis is:

a) Bullous pemphigoid

b) Pemphigus vulgaris

c) Pemphigus foliaceus

d) Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

e) Toxic epidermal necrolysis

To learn the answers, go to page 2

{{pagebreak}}

Answers

1. These ankle lesions suggest:

e) Livedoid vasculitis, atrophie blanche

Livedoid vasculitis, also known as segmental hyalinizing vasculitis, is a condition involving lower extremities, such as the lateral ankles. The condition is characterized by livedoid purpura, telangiectasia, and hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation. Atrophy producing “ivory white” scarring is also characteristic, in addition to ankle edema, bluish nodules, and ulcerations.

Histology has shown superficial, mid and deep vascular involvement with thickening and hyalinization and a relatively sparse inflammatory infiltrate. Immunoglobulin and complement components have been seen in vessel walls. An association with decreased blood fibrinolytic activity has led to the use of agents that inhibit clotting or promote fibrinolysis. The cause of livedoid vasculitis is unknown.

References

Schroeter AL, Diaz-Perez JL, Winkelmann RK, Jordan RE. Livedo vasculitis (the vasculitis of atrophie blanche). Immunohistopathologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111(2):188-193.

Shornick JK, Nicholes BK, Bergstresser PR, Gilliam JN. Idiopathic atrophie blanche. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8(6):792-798.

Heller I, Isakov A, Topilsky M. American College of Rheumatology Criteria for the diagnosis of vasculitis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(10):861.

Jayne D. Evidence-based treatment of systemic vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(6):585-595.

Gross WL, Trabandt A, Reinhold-Keller E. Diagnosis and evaluation of vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(3):245-252.

2. Histology of these lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis would most likely show:

d) Septal panniculitis

Erythema nodosum are tender lesions that arise on the extensor lower legs and dorsal feet of a patient with sarcoidosis until proven otherwise. Additionally, erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can occur as an isolated or idiopathic event, which may be associated with systematic diseases (Behçet syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, streptococcal, mycobacterial, deep fungal, and protozoan disease). In addition, it can be caused by drugs such as sulfonamides, penicillin, and BCP. Other causes of septal panniculitis can be scleroderma, necrotizing vasculitis, eosinophilic facitis, and thrombophlebitis.

Reference

Histopathology of the Skin, 1st ed. Ackerman (ed.), pp. 782-793.

3. The diagnosis is:

b) Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease characterized by flaccid blisters, erosions, and Nikolsky-positive skin. Epitheilial fragility is indicated by irregular configuration of many of the blisters, as well as the presence of overlying fragments of epidermis. No scars or millia are present.

References

Fitzpatrick TB. Dermatology in General Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1993:606-615.

Nishikawa T, Hashimoto T, Shimizu H, Ebihara T, Amagai M. Pemphigus: from immunofluorescence to molecular biology. J Dermatol Sci. 1996;12(1):1-9.

Amagai M. Autoimmunity against desmosomal cadherins in pemphigus. J Dermatol Sci. 1999;20(2):92-102.

Stanley JR. Pathophysiology and therapy of pemphigus in the 21st century. J Dermatol. 2001;28(11):645-646.

Tóth GG, Jonkman MF. Therapy of pemphigus. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(6):761-767.

The contents of these questions are taken from the Galderma Pre-Board Webinar. The Pre-Board Webinar is now an online course. For details, go to www.pre-board.com. The program will be available from April 15, 2016 to November 15, 2016.

1. These ankle lesions suggest:

a) Necrobiosis lipoidica

b) Morphea

c) Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

d) Livedo reticularis

e) Livedoid vasculitis, atrophie blanche

2. Histology of these lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis would most likely show:

a) Granulomatous inflammation

b) Lobular panniculitis

c) Necrotizing vasculitis

d) Septal panniculitis

e) Thrombophlebitis

3. The diagnosis is:

a) Bullous pemphigoid

b) Pemphigus vulgaris

c) Pemphigus foliaceus

d) Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

e) Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Answers

1. These ankle lesions suggest:

e) Livedoid vasculitis, atrophie blanche

Livedoid vasculitis, also known as segmental hyalinizing vasculitis, is a condition involving lower extremities, such as the lateral ankles. The condition is characterized by livedoid purpura, telangiectasia, and hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation. Atrophy producing “ivory white” scarring is also characteristic, in addition to ankle edema, bluish nodules, and ulcerations.

Histology has shown superficial, mid and deep vascular involvement with thickening and hyalinization and a relatively sparse inflammatory infiltrate. Immunoglobulin and complement components have been seen in vessel walls. An association with decreased blood fibrinolytic activity has led to the use of agents that inhibit clotting or promote fibrinolysis. The cause of livedoid vasculitis is unknown.

References

Schroeter AL, Diaz-Perez JL, Winkelmann RK, Jordan RE. Livedo vasculitis (the vasculitis of atrophie blanche). Immunohistopathologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111(2):188-193.

Shornick JK, Nicholes BK, Bergstresser PR, Gilliam JN. Idiopathic atrophie blanche. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8(6):792-798.

Heller I, Isakov A, Topilsky M. American College of Rheumatology Criteria for the diagnosis of vasculitis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(10):861.

Jayne D. Evidence-based treatment of systemic vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(6):585-595.

Gross WL, Trabandt A, Reinhold-Keller E. Diagnosis and evaluation of vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(3):245-252.

2. Histology of these lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis would most likely show:

d) Septal panniculitis

Erythema nodosum are tender lesions that arise on the extensor lower legs and dorsal feet of a patient with sarcoidosis until proven otherwise. Additionally, erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can occur as an isolated or idiopathic event, which may be associated with systematic diseases (Behçet syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, streptococcal, mycobacterial, deep fungal, and protozoan disease). In addition, it can be caused by drugs such as sulfonamides, penicillin, and BCP. Other causes of septal panniculitis can be scleroderma, necrotizing vasculitis, eosinophilic facitis, and thrombophlebitis.

Reference

Histopathology of the Skin, 1st ed. Ackerman (ed.), pp. 782-793.

3. The diagnosis is:

b) Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease characterized by flaccid blisters, erosions, and Nikolsky-positive skin. Epitheilial fragility is indicated by irregular configuration of many of the blisters, as well as the presence of overlying fragments of epidermis. No scars or millia are present.

References

Fitzpatrick TB. Dermatology in General Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1993:606-615.

Nishikawa T, Hashimoto T, Shimizu H, Ebihara T, Amagai M. Pemphigus: from immunofluorescence to molecular biology. J Dermatol Sci. 1996;12(1):1-9.

Amagai M. Autoimmunity against desmosomal cadherins in pemphigus. J Dermatol Sci. 1999;20(2):92-102.

Stanley JR. Pathophysiology and therapy of pemphigus in the 21st century. J Dermatol. 2001;28(11):645-646.

Tóth GG, Jonkman MF. Therapy of pemphigus. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(6):761-767.

Answers

1. These ankle lesions suggest:

e) Livedoid vasculitis, atrophie blanche

Livedoid vasculitis, also known as segmental hyalinizing vasculitis, is a condition involving lower extremities, such as the lateral ankles. The condition is characterized by livedoid purpura, telangiectasia, and hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation. Atrophy producing “ivory white” scarring is also characteristic, in addition to ankle edema, bluish nodules, and ulcerations.

Histology has shown superficial, mid and deep vascular involvement with thickening and hyalinization and a relatively sparse inflammatory infiltrate. Immunoglobulin and complement components have been seen in vessel walls. An association with decreased blood fibrinolytic activity has led to the use of agents that inhibit clotting or promote fibrinolysis. The cause of livedoid vasculitis is unknown.

References

Schroeter AL, Diaz-Perez JL, Winkelmann RK, Jordan RE. Livedo vasculitis (the vasculitis of atrophie blanche). Immunohistopathologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111(2):188-193.

Shornick JK, Nicholes BK, Bergstresser PR, Gilliam JN. Idiopathic atrophie blanche. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8(6):792-798.

Heller I, Isakov A, Topilsky M. American College of Rheumatology Criteria for the diagnosis of vasculitis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(10):861.

Jayne D. Evidence-based treatment of systemic vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(6):585-595.

Gross WL, Trabandt A, Reinhold-Keller E. Diagnosis and evaluation of vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(3):245-252.

2. Histology of these lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis would most likely show:

d) Septal panniculitis

Erythema nodosum are tender lesions that arise on the extensor lower legs and dorsal feet of a patient with sarcoidosis until proven otherwise. Additionally, erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can occur as an isolated or idiopathic event, which may be associated with systematic diseases (Behçet syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, streptococcal, mycobacterial, deep fungal, and protozoan disease). In addition, it can be caused by drugs such as sulfonamides, penicillin, and BCP. Other causes of septal panniculitis can be scleroderma, necrotizing vasculitis, eosinophilic facitis, and thrombophlebitis.

Reference

Histopathology of the Skin, 1st ed. Ackerman (ed.), pp. 782-793.

3. The diagnosis is:

b) Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease characterized by flaccid blisters, erosions, and Nikolsky-positive skin. Epitheilial fragility is indicated by irregular configuration of many of the blisters, as well as the presence of overlying fragments of epidermis. No scars or millia are present.

References

Fitzpatrick TB. Dermatology in General Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1993:606-615.

Nishikawa T, Hashimoto T, Shimizu H, Ebihara T, Amagai M. Pemphigus: from immunofluorescence to molecular biology. J Dermatol Sci. 1996;12(1):1-9.

Amagai M. Autoimmunity against desmosomal cadherins in pemphigus. J Dermatol Sci. 1999;20(2):92-102.

Stanley JR. Pathophysiology and therapy of pemphigus in the 21st century. J Dermatol. 2001;28(11):645-646.

Tóth GG, Jonkman MF. Therapy of pemphigus. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(6):761-767.