A 57-year-old male with Fitzpatrick skin type III was referred by his primary care physician for the evaluation and management of a newly developed lesion that on exam was consistent with an acrochordon. However, during a full-body skin examination, we noted a 1.3 cm x 0.8 cm well-circumscribed light pink plaque with slight scale and no ulceration on the left medial ankle. The superior border of the lesion was slightly more elevated and small fine vessels were evident on close examination (Figures 1A and 1B). The patient had no personal family history of skin cancer. The patient had no known medical problems, took no medications and denied any trauma to the area.

The ankle lesion was not of concern to the patient, but upon questioning he reported it to have been present for several months. He was unsure if it was increasing in size and denied any symptoms such as pain, pruritus or bleeding. A biopsy using tangential shave technique of the lesion was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

To learn the answer, go to page 2

{{pagebreak}}

Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma with histologic features of Hidroacanthoma Simplex and Dermal Tumor in the same lesion

Aporoma is a benign neoplasm that originates from the intraepidermal portion of the sweat duct.1 Poromas were first described in 1956 in a case series of 5 patients, each of whom presented with a lesion on the foot.2 While poromas were originally described as originating from the eccrine sweat gland, some tumors are of apocrine origin.1,2 Nevertheless, the terms eccrine and poroma are commonly linked together by many dermatologists.3

Clinical Presentation

Poromas classically present as a solitary, dome shaped, red or pink papule, plaque or nodule.1 Bluish and pigmented lesions have also been described.4 They are usually solitary lesions with either a smooth, dull, shiny, scaly or verrucous surface.5,6 Erosions, ulcerations and crust may be present as a result of trauma.5 Pedunculated lesions have also been reported. 7

Poromas are most commonly acral in location, especially on the soles or sides of the foot (Figures 1A and B); however, they may occur on any cutaneous surface with eccrine or apocrine glands.6 The face and scalp are also common locations in the middle-aged and elderly.7 They are usually slow growing and asymptomatic, although pain or pruritus may be present. 1 The rare clinical variant termed eccrine poromatosis is characterized by multiple poromas in an acral or widespread distribution.3,8

Each benign poroid neoplasm also has a malignant counterpart. Porocarcinomas may arise from a preexisting poroma or de novo.6,9 The number of porocarcinomas that develop from preexisting poromas is largely unknown, as studies have produced divergent data.6 The rarity of porocarcinomas makes it difficult to quantify rates of malignant transformation; however, the presence of some lesions for 20 or more years suggests malignant degeneration from benign lesions.10,11

Eccrine porocarcinomas are typically described as firm erythematous to violaceous nodules that most commonly occur on the lower extremities.9 When transformation occurs, signs and symptoms such as spontaneous bleeding, ulceration, itching, pain and sudden growth over a short period of time may serve as potential markers.9

Epidemiology

Neoplasms of eccrine or apocrine origin are relatively uncommon. Sweat gland neoplasms represent about 1% of all primary cutaneous tumors and approximately 10% of these are eccrine poromas.12 They most commonly occur in the middle-aged to elderly population with no gender or ethnic predilection.1,13 There have been several case reports of poromas originating after long-term radiation exposure.14,15 Additionally, poromas may be found as secondary lesions arising within a nevus sebaceous or an epidermal nevus.16,17 They have also been reported in association with pregnancy.18

Eccrine porocarcinoma, on the other hand, is a rare tumor, typically found in those age 60 and older and most commonly on the lower extremities.6 The trunk, face, scalp, upper extremities, vulva and penis are other reported sites.6,19,20

Etiopathogenesis & Histopathology

The classification of poroid tumors is a somewhat confusing area in dermatopathology. In addition to eccrine poroma, there are 3 other poroid neoplasms including hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor and poroid (eccrine) hidradenoma. These benign poroid tumors comprise a family of tumors with similar architectural and cytologic features.5 As a result, some argue that these 4 tumors represent a single pathologic process rather than distinct entities.5,13 Others classify the poroid and hidradenoma groups separately.21 Our discussion will favor the former classification as defined by Abenoza and Ackerman.5

Poromas are classically thought to originate from poroid cells located adjacent to the luminal cells of the upper intradermal and lower intraepidermal portion of the eccrine duct.5 The other main cell type in poromas, “cuticular” cells, are considered to be luminal cell islands based on their morphologic and staining similarities to normal luminal duct cells.4

More recent immunohistochemical studies, however, suggest that poromas are derived from the basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge and lower acrosyringium.4 They differentiate toward the upper acrosyringium into larger, “cuticular” cells. The basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge merge with the adjacent epidermis.4 Because the length of this sweat duct ridge is highly variable, the initial site of tumor origination along this ridge may account for the various forms of poroid tumors.4

The histologic appearance of poroid neoplasms is due to a mixture of predominately poroid cells admixed with cuticular cells. Poroid cells are uniform, small cuboidal cells with oval to round nuclei that show ductal differentiation.4,13 They are smaller than epidermal keratinocytes and contain some glycogen.21 Cuticular cells are larger cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and pale staining nucleus.4 Necrosis en masse is a common feature of poromas, which give rise to the cystic spaces these tumors commonly display. Ductal structures are variable in number, but also commonly present in these neoplasms. Apocrine poromas, by contrast, display tubular (instead of ductal) structures that are lined by columnar cells with holocrine secretion.3 The stroma of poromas is often highly vascular, which accounts for the clinical resemblance to pyogenic granulomas.3

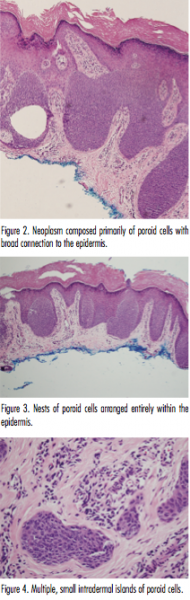

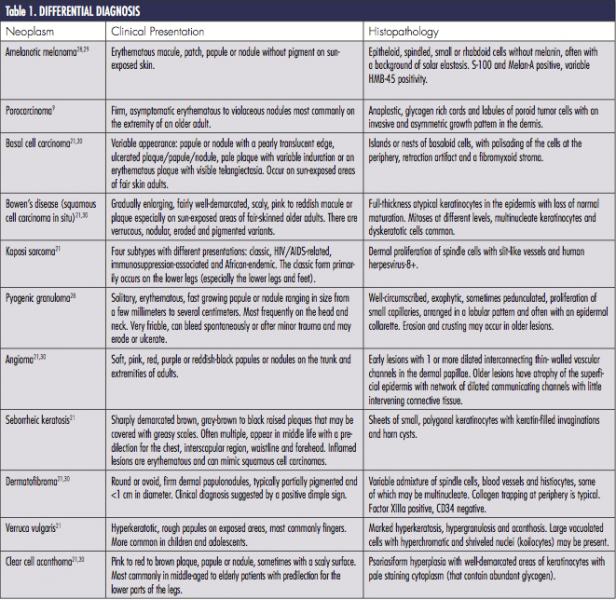

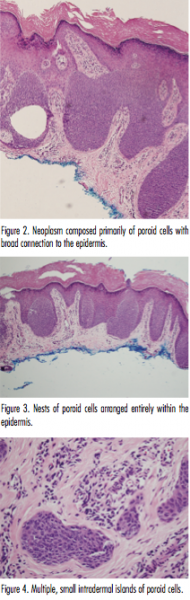

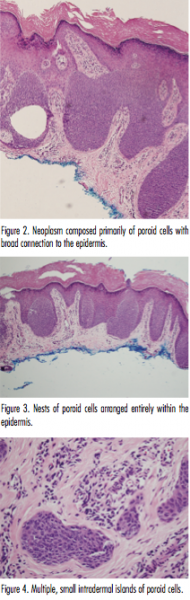

What primarily distinguishes the poroid group of neoplasms from one another is where the neoplastic cells are situated.13 The classic eccrine poroma displays a lobular growth pattern with a broad connection to the overlying epidermis. In hidroacanthoma simplex, the neoplastic cells are arranged in nests and contained entirely within the epidermis. Dermal duct tumors have multiple, small intradermal islands, whereas poroid hidradenomas consist of a large dermal nodule of neoplastic cells. 4,21 Clear distinction between the poroid neoplasms is difficult when examining serial sections of a single poroid neoplasm.5 The presence of 2 or 3 of these tumors in a single lesion, as is seen in our case, has been previously described.22,23 These 4 tumors, therefore, are best viewed as variants of a single benign poroid growth process, rather than distinct entities.5,13 Abenoza and Ackerman collectively refers to these tumors as poromas.5

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

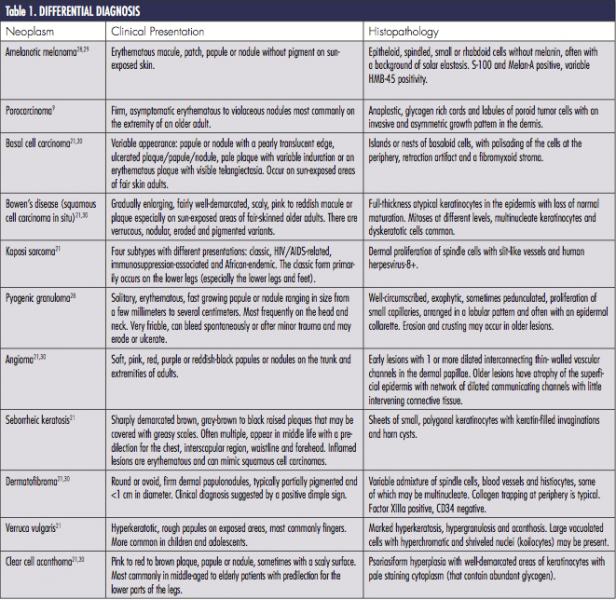

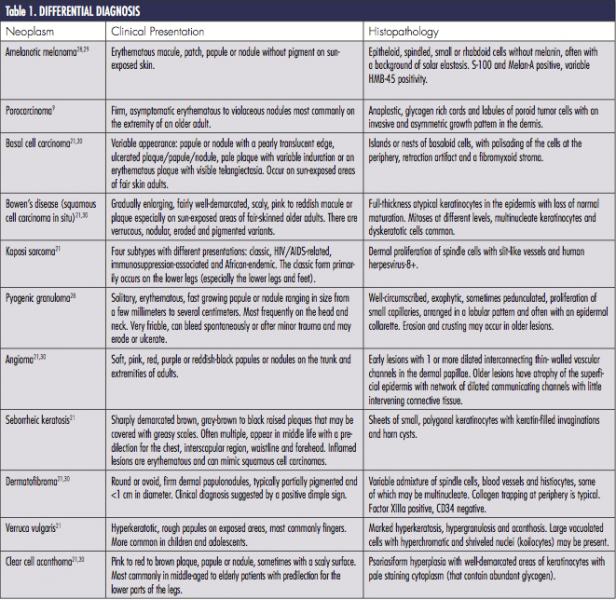

The differential diagnosis of poromas is broad and includes a number of malignant and benign neoplasms (Table). An acral location may help to narrow the differential. In addition, dermoscopy may support a physician’s clinical suspicion; however, many dermoscopic features of poromas are non-specific and have considerable overlap with neoplasms in the differential diagnosis.6,24 Therefore, histopathology is often necessary for diagnosis. As such, when poromas are suspected clinically, biopsy is recommended to rule out other neoplasms.

Treatment

Poromas are benign neoplasms; therefore, surgical treatment is optional.3,25 Treatment options include simple excision, therapeutic shave removal, electrodesiccation and curettage or CO2 laser removal.3,25

Some authors recommend that eccrine poromas be surgically excised due to the risk of malignant degeneration.6,7,9 As previously stated, porocarcinoma can arise de novo, but may also arise within a preexisting benign poroma.7 Treatment for porocarcinoma includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.26 Chemotherapy and/or radiation may be added if the lesion has metastasized.27 Despite surgical treatment, local reoccurrence is common (20%).27

Our Patient

The initial clinical impression in our patient favored eccrine poroma given the morphological appearance and acral location; however, other  neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

Histologic evaluation showed multiple lobules of predominately uniform cuboidal cells with a broad connection to the epidermis (Figure 2). A few larger cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and pale staining nuclei were noted within these lobules. The stroma was rather vascular; however, no necrosis en masse was found. These features were consistent with a diagnosis of eccrine poroma. Other sections demonstrated nests of predominately poroid cells contained entirely within the epidermis, as seen in hidroacanthoma simplex (Figure 3). Still additional sections showed small islands of poroid cells as seen in dermal duct tumor (Figure 4). Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up so additional treatment options could not be discussed.

Conclusion

Our case represents a typical presentation of a relatively uncommon adnexal neoplasm. As is common with poromas, our case was seen in a middle-aged adult and on an acral location.1 The clinical presentation of poromas can mimic those of many other benign and malignant tumors; therefore, biopsy is necessary in confirming the diagnosis. The histopathology of our case demonstrates features of hidroacathoma simplex, eccrine poroma and dermal duct tumor, depending on the section observed. Further immunohistochemical studies may better define and classify these lesions.

Dr. Serravallo is with Hackensack University Medical Group in Hackensack NJ.

Dr. Alapati is chief of dermatology at Brooklyn Veterans Affairs Medical Center Dermatology Service in Brooklyn, NY.

Dr. Khachemoune, the Section Editor of Derm DX, is with the Department of Dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate in Brooklyn, NY.

Disclosure: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(9):1053-1061.

2. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74(5):511-521.

3. McCalmont TH. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012:1841-1846.

4. Battistella M, Langbein L, Peltre B, Cribier B. From hidroacanthoma simplex to poroid hidradenoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemic study of poroid neoplasms and reappraisal of their histogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32(5):459-468.

5. Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Poromas. In: Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms with Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1990:113-183.

6. Sgouros D, Piana S, Argenziano G, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathological features of eccrine poroid neoplasms. Dermatology. 2013;227(2):175-179.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, May K, Motley RJ. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(1):84-86.

8. Goldner R. Eccrine poromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101(5):606-608.

9. Brown CW Jr, Dy LC. Eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(6):433-438.

10. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(6):710-720.

11. Shaw M, McKee PH, Lowe D, Black MM. Malignant eccrine poroma: a study of twenty-seven cases. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107(6):675-680.

12. Pylyser K, De Wolf-Peeters C, Marien K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167(5):243-249.

13. Casper DJ, Glass FL, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88(5):227-229.

14. Sidro-Sarto M, Guimerá-Martin-Neda F, Perez-Robayna N, et al. Eccrine poroma arising in chronic radiation dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(12):1517-1519.

15. Deckelbaum S, Touloei K, Shitabata PK, Sire DJ, Horowitz D. Eccrine poromatosis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(5):543-548.

16. Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez YE. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of a series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(2):108-118.

17. Jeon J, Kim JH, Baek YS, Kim A, Seo SH, Oh CH. Eccrine poroma and eccrine porocarcinoma in linear epidermal nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(5):430-432.

18. Guimerá Martín-Neda F, García Bustínduy M, Noda Cabrera A, Sánchez González R, García Montelongo R. A rapidly growing eccrine poroma in a pregnant woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(1):124-126.

19. Liegl B, Regauer S. Eccrine carcinoma (nodular porocarcinoma) of the vulva. Histopathology. 2005;47(3):324-326.

20. Grayson W, Loubser JS. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the penis. J Urol. 2003;169(2):611-612.

21. Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

22. Chiu HH, Lan CC, Wu CS, Cheng GS, Tsai KB, Chen PH. A single lesion showing features of pigmented eccrine poroma and poroid hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(9):861-865.

23. Kakinuma H, Miyamoto R, Iwasawa U, Babe S, Suzuki H. Three subtypes of poroid neoplasia in a single lesion: eccrine poroma, hidroacanthoma simplex, and dermal duct tumor. Histologic, histochemical, and ultrastructural findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16(1):66-72.

24. Nicolino R, Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, et al. Dermoscopy of eccrine poroma. Dermatology. 2007;215(2):160-163.

25. Mahajan RS, Parikh AA, Chhajlani NP, Bilimoria FE. Eccrine poroma on the face: an atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(1):88-90.

26. Sharathkumar HK, Hemalatha AL, Ramesh DB, Soni A, Revathi V. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(12):2966-2967.

27. Cowden A, Dans M, Giuseppe M, Junkins-Hopkins J, Van Voorhees AS. Eccrine porocarcinoma arising in two African American patients: distinct presentations both treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(2):146-150.

28. Junck M, Huerter CJ, Sarma DP. Rapidly growing hemorrhagic papule on the cheek of a 54-year-old man. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(1):11.

29. Choi YD, Chun SM, Jin SA, et al. Amelanotic acral melanomas: clinicopathological, BRAF mutation, and KIT aberration analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):700-707.

30. Giacomel J, Zalaudek I. Pink lesions. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(4):649-678.

A 57-year-old male with Fitzpatrick skin type III was referred by his primary care physician for the evaluation and management of a newly developed lesion that on exam was consistent with an acrochordon. However, during a full-body skin examination, we noted a 1.3 cm x 0.8 cm well-circumscribed light pink plaque with slight scale and no ulceration on the left medial ankle. The superior border of the lesion was slightly more elevated and small fine vessels were evident on close examination (Figures 1A and 1B). The patient had no personal family history of skin cancer. The patient had no known medical problems, took no medications and denied any trauma to the area.

The ankle lesion was not of concern to the patient, but upon questioning he reported it to have been present for several months. He was unsure if it was increasing in size and denied any symptoms such as pain, pruritus or bleeding. A biopsy using tangential shave technique of the lesion was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma with histologic features of Hidroacanthoma Simplex and Dermal Tumor in the same lesion

Aporoma is a benign neoplasm that originates from the intraepidermal portion of the sweat duct.1 Poromas were first described in 1956 in a case series of 5 patients, each of whom presented with a lesion on the foot.2 While poromas were originally described as originating from the eccrine sweat gland, some tumors are of apocrine origin.1,2 Nevertheless, the terms eccrine and poroma are commonly linked together by many dermatologists.3

Clinical Presentation

Poromas classically present as a solitary, dome shaped, red or pink papule, plaque or nodule.1 Bluish and pigmented lesions have also been described.4 They are usually solitary lesions with either a smooth, dull, shiny, scaly or verrucous surface.5,6 Erosions, ulcerations and crust may be present as a result of trauma.5 Pedunculated lesions have also been reported. 7

Poromas are most commonly acral in location, especially on the soles or sides of the foot (Figures 1A and B); however, they may occur on any cutaneous surface with eccrine or apocrine glands.6 The face and scalp are also common locations in the middle-aged and elderly.7 They are usually slow growing and asymptomatic, although pain or pruritus may be present. 1 The rare clinical variant termed eccrine poromatosis is characterized by multiple poromas in an acral or widespread distribution.3,8

Each benign poroid neoplasm also has a malignant counterpart. Porocarcinomas may arise from a preexisting poroma or de novo.6,9 The number of porocarcinomas that develop from preexisting poromas is largely unknown, as studies have produced divergent data.6 The rarity of porocarcinomas makes it difficult to quantify rates of malignant transformation; however, the presence of some lesions for 20 or more years suggests malignant degeneration from benign lesions.10,11

Eccrine porocarcinomas are typically described as firm erythematous to violaceous nodules that most commonly occur on the lower extremities.9 When transformation occurs, signs and symptoms such as spontaneous bleeding, ulceration, itching, pain and sudden growth over a short period of time may serve as potential markers.9

Epidemiology

Neoplasms of eccrine or apocrine origin are relatively uncommon. Sweat gland neoplasms represent about 1% of all primary cutaneous tumors and approximately 10% of these are eccrine poromas.12 They most commonly occur in the middle-aged to elderly population with no gender or ethnic predilection.1,13 There have been several case reports of poromas originating after long-term radiation exposure.14,15 Additionally, poromas may be found as secondary lesions arising within a nevus sebaceous or an epidermal nevus.16,17 They have also been reported in association with pregnancy.18

Eccrine porocarcinoma, on the other hand, is a rare tumor, typically found in those age 60 and older and most commonly on the lower extremities.6 The trunk, face, scalp, upper extremities, vulva and penis are other reported sites.6,19,20

Etiopathogenesis & Histopathology

The classification of poroid tumors is a somewhat confusing area in dermatopathology. In addition to eccrine poroma, there are 3 other poroid neoplasms including hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor and poroid (eccrine) hidradenoma. These benign poroid tumors comprise a family of tumors with similar architectural and cytologic features.5 As a result, some argue that these 4 tumors represent a single pathologic process rather than distinct entities.5,13 Others classify the poroid and hidradenoma groups separately.21 Our discussion will favor the former classification as defined by Abenoza and Ackerman.5

Poromas are classically thought to originate from poroid cells located adjacent to the luminal cells of the upper intradermal and lower intraepidermal portion of the eccrine duct.5 The other main cell type in poromas, “cuticular” cells, are considered to be luminal cell islands based on their morphologic and staining similarities to normal luminal duct cells.4

More recent immunohistochemical studies, however, suggest that poromas are derived from the basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge and lower acrosyringium.4 They differentiate toward the upper acrosyringium into larger, “cuticular” cells. The basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge merge with the adjacent epidermis.4 Because the length of this sweat duct ridge is highly variable, the initial site of tumor origination along this ridge may account for the various forms of poroid tumors.4

The histologic appearance of poroid neoplasms is due to a mixture of predominately poroid cells admixed with cuticular cells. Poroid cells are uniform, small cuboidal cells with oval to round nuclei that show ductal differentiation.4,13 They are smaller than epidermal keratinocytes and contain some glycogen.21 Cuticular cells are larger cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and pale staining nucleus.4 Necrosis en masse is a common feature of poromas, which give rise to the cystic spaces these tumors commonly display. Ductal structures are variable in number, but also commonly present in these neoplasms. Apocrine poromas, by contrast, display tubular (instead of ductal) structures that are lined by columnar cells with holocrine secretion.3 The stroma of poromas is often highly vascular, which accounts for the clinical resemblance to pyogenic granulomas.3

What primarily distinguishes the poroid group of neoplasms from one another is where the neoplastic cells are situated.13 The classic eccrine poroma displays a lobular growth pattern with a broad connection to the overlying epidermis. In hidroacanthoma simplex, the neoplastic cells are arranged in nests and contained entirely within the epidermis. Dermal duct tumors have multiple, small intradermal islands, whereas poroid hidradenomas consist of a large dermal nodule of neoplastic cells. 4,21 Clear distinction between the poroid neoplasms is difficult when examining serial sections of a single poroid neoplasm.5 The presence of 2 or 3 of these tumors in a single lesion, as is seen in our case, has been previously described.22,23 These 4 tumors, therefore, are best viewed as variants of a single benign poroid growth process, rather than distinct entities.5,13 Abenoza and Ackerman collectively refers to these tumors as poromas.5

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of poromas is broad and includes a number of malignant and benign neoplasms (Table). An acral location may help to narrow the differential. In addition, dermoscopy may support a physician’s clinical suspicion; however, many dermoscopic features of poromas are non-specific and have considerable overlap with neoplasms in the differential diagnosis.6,24 Therefore, histopathology is often necessary for diagnosis. As such, when poromas are suspected clinically, biopsy is recommended to rule out other neoplasms.

Treatment

Poromas are benign neoplasms; therefore, surgical treatment is optional.3,25 Treatment options include simple excision, therapeutic shave removal, electrodesiccation and curettage or CO2 laser removal.3,25

Some authors recommend that eccrine poromas be surgically excised due to the risk of malignant degeneration.6,7,9 As previously stated, porocarcinoma can arise de novo, but may also arise within a preexisting benign poroma.7 Treatment for porocarcinoma includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.26 Chemotherapy and/or radiation may be added if the lesion has metastasized.27 Despite surgical treatment, local reoccurrence is common (20%).27

Our Patient

The initial clinical impression in our patient favored eccrine poroma given the morphological appearance and acral location; however, other  neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

Histologic evaluation showed multiple lobules of predominately uniform cuboidal cells with a broad connection to the epidermis (Figure 2). A few larger cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and pale staining nuclei were noted within these lobules. The stroma was rather vascular; however, no necrosis en masse was found. These features were consistent with a diagnosis of eccrine poroma. Other sections demonstrated nests of predominately poroid cells contained entirely within the epidermis, as seen in hidroacanthoma simplex (Figure 3). Still additional sections showed small islands of poroid cells as seen in dermal duct tumor (Figure 4). Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up so additional treatment options could not be discussed.

Conclusion

Our case represents a typical presentation of a relatively uncommon adnexal neoplasm. As is common with poromas, our case was seen in a middle-aged adult and on an acral location.1 The clinical presentation of poromas can mimic those of many other benign and malignant tumors; therefore, biopsy is necessary in confirming the diagnosis. The histopathology of our case demonstrates features of hidroacathoma simplex, eccrine poroma and dermal duct tumor, depending on the section observed. Further immunohistochemical studies may better define and classify these lesions.

Dr. Serravallo is with Hackensack University Medical Group in Hackensack NJ.

Dr. Alapati is chief of dermatology at Brooklyn Veterans Affairs Medical Center Dermatology Service in Brooklyn, NY.

Dr. Khachemoune, the Section Editor of Derm DX, is with the Department of Dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate in Brooklyn, NY.

Disclosure: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(9):1053-1061.

2. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74(5):511-521.

3. McCalmont TH. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012:1841-1846.

4. Battistella M, Langbein L, Peltre B, Cribier B. From hidroacanthoma simplex to poroid hidradenoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemic study of poroid neoplasms and reappraisal of their histogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32(5):459-468.

5. Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Poromas. In: Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms with Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1990:113-183.

6. Sgouros D, Piana S, Argenziano G, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathological features of eccrine poroid neoplasms. Dermatology. 2013;227(2):175-179.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, May K, Motley RJ. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(1):84-86.

8. Goldner R. Eccrine poromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101(5):606-608.

9. Brown CW Jr, Dy LC. Eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(6):433-438.

10. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(6):710-720.

11. Shaw M, McKee PH, Lowe D, Black MM. Malignant eccrine poroma: a study of twenty-seven cases. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107(6):675-680.

12. Pylyser K, De Wolf-Peeters C, Marien K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167(5):243-249.

13. Casper DJ, Glass FL, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88(5):227-229.

14. Sidro-Sarto M, Guimerá-Martin-Neda F, Perez-Robayna N, et al. Eccrine poroma arising in chronic radiation dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(12):1517-1519.

15. Deckelbaum S, Touloei K, Shitabata PK, Sire DJ, Horowitz D. Eccrine poromatosis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(5):543-548.

16. Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez YE. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of a series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(2):108-118.

17. Jeon J, Kim JH, Baek YS, Kim A, Seo SH, Oh CH. Eccrine poroma and eccrine porocarcinoma in linear epidermal nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(5):430-432.

18. Guimerá Martín-Neda F, García Bustínduy M, Noda Cabrera A, Sánchez González R, García Montelongo R. A rapidly growing eccrine poroma in a pregnant woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(1):124-126.

19. Liegl B, Regauer S. Eccrine carcinoma (nodular porocarcinoma) of the vulva. Histopathology. 2005;47(3):324-326.

20. Grayson W, Loubser JS. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the penis. J Urol. 2003;169(2):611-612.

21. Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

22. Chiu HH, Lan CC, Wu CS, Cheng GS, Tsai KB, Chen PH. A single lesion showing features of pigmented eccrine poroma and poroid hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(9):861-865.

23. Kakinuma H, Miyamoto R, Iwasawa U, Babe S, Suzuki H. Three subtypes of poroid neoplasia in a single lesion: eccrine poroma, hidroacanthoma simplex, and dermal duct tumor. Histologic, histochemical, and ultrastructural findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16(1):66-72.

24. Nicolino R, Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, et al. Dermoscopy of eccrine poroma. Dermatology. 2007;215(2):160-163.

25. Mahajan RS, Parikh AA, Chhajlani NP, Bilimoria FE. Eccrine poroma on the face: an atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(1):88-90.

26. Sharathkumar HK, Hemalatha AL, Ramesh DB, Soni A, Revathi V. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(12):2966-2967.

27. Cowden A, Dans M, Giuseppe M, Junkins-Hopkins J, Van Voorhees AS. Eccrine porocarcinoma arising in two African American patients: distinct presentations both treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(2):146-150.

28. Junck M, Huerter CJ, Sarma DP. Rapidly growing hemorrhagic papule on the cheek of a 54-year-old man. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(1):11.

29. Choi YD, Chun SM, Jin SA, et al. Amelanotic acral melanomas: clinicopathological, BRAF mutation, and KIT aberration analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):700-707.

30. Giacomel J, Zalaudek I. Pink lesions. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(4):649-678.

A 57-year-old male with Fitzpatrick skin type III was referred by his primary care physician for the evaluation and management of a newly developed lesion that on exam was consistent with an acrochordon. However, during a full-body skin examination, we noted a 1.3 cm x 0.8 cm well-circumscribed light pink plaque with slight scale and no ulceration on the left medial ankle. The superior border of the lesion was slightly more elevated and small fine vessels were evident on close examination (Figures 1A and 1B). The patient had no personal family history of skin cancer. The patient had no known medical problems, took no medications and denied any trauma to the area.

The ankle lesion was not of concern to the patient, but upon questioning he reported it to have been present for several months. He was unsure if it was increasing in size and denied any symptoms such as pain, pruritus or bleeding. A biopsy using tangential shave technique of the lesion was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

,

A 57-year-old male with Fitzpatrick skin type III was referred by his primary care physician for the evaluation and management of a newly developed lesion that on exam was consistent with an acrochordon. However, during a full-body skin examination, we noted a 1.3 cm x 0.8 cm well-circumscribed light pink plaque with slight scale and no ulceration on the left medial ankle. The superior border of the lesion was slightly more elevated and small fine vessels were evident on close examination (Figures 1A and 1B). The patient had no personal family history of skin cancer. The patient had no known medical problems, took no medications and denied any trauma to the area.

The ankle lesion was not of concern to the patient, but upon questioning he reported it to have been present for several months. He was unsure if it was increasing in size and denied any symptoms such as pain, pruritus or bleeding. A biopsy using tangential shave technique of the lesion was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

To learn the answer, go to page 2

{{pagebreak}}

Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma with histologic features of Hidroacanthoma Simplex and Dermal Tumor in the same lesion

Aporoma is a benign neoplasm that originates from the intraepidermal portion of the sweat duct.1 Poromas were first described in 1956 in a case series of 5 patients, each of whom presented with a lesion on the foot.2 While poromas were originally described as originating from the eccrine sweat gland, some tumors are of apocrine origin.1,2 Nevertheless, the terms eccrine and poroma are commonly linked together by many dermatologists.3

Clinical Presentation

Poromas classically present as a solitary, dome shaped, red or pink papule, plaque or nodule.1 Bluish and pigmented lesions have also been described.4 They are usually solitary lesions with either a smooth, dull, shiny, scaly or verrucous surface.5,6 Erosions, ulcerations and crust may be present as a result of trauma.5 Pedunculated lesions have also been reported. 7

Poromas are most commonly acral in location, especially on the soles or sides of the foot (Figures 1A and B); however, they may occur on any cutaneous surface with eccrine or apocrine glands.6 The face and scalp are also common locations in the middle-aged and elderly.7 They are usually slow growing and asymptomatic, although pain or pruritus may be present. 1 The rare clinical variant termed eccrine poromatosis is characterized by multiple poromas in an acral or widespread distribution.3,8

Each benign poroid neoplasm also has a malignant counterpart. Porocarcinomas may arise from a preexisting poroma or de novo.6,9 The number of porocarcinomas that develop from preexisting poromas is largely unknown, as studies have produced divergent data.6 The rarity of porocarcinomas makes it difficult to quantify rates of malignant transformation; however, the presence of some lesions for 20 or more years suggests malignant degeneration from benign lesions.10,11

Eccrine porocarcinomas are typically described as firm erythematous to violaceous nodules that most commonly occur on the lower extremities.9 When transformation occurs, signs and symptoms such as spontaneous bleeding, ulceration, itching, pain and sudden growth over a short period of time may serve as potential markers.9

Epidemiology

Neoplasms of eccrine or apocrine origin are relatively uncommon. Sweat gland neoplasms represent about 1% of all primary cutaneous tumors and approximately 10% of these are eccrine poromas.12 They most commonly occur in the middle-aged to elderly population with no gender or ethnic predilection.1,13 There have been several case reports of poromas originating after long-term radiation exposure.14,15 Additionally, poromas may be found as secondary lesions arising within a nevus sebaceous or an epidermal nevus.16,17 They have also been reported in association with pregnancy.18

Eccrine porocarcinoma, on the other hand, is a rare tumor, typically found in those age 60 and older and most commonly on the lower extremities.6 The trunk, face, scalp, upper extremities, vulva and penis are other reported sites.6,19,20

Etiopathogenesis & Histopathology

The classification of poroid tumors is a somewhat confusing area in dermatopathology. In addition to eccrine poroma, there are 3 other poroid neoplasms including hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor and poroid (eccrine) hidradenoma. These benign poroid tumors comprise a family of tumors with similar architectural and cytologic features.5 As a result, some argue that these 4 tumors represent a single pathologic process rather than distinct entities.5,13 Others classify the poroid and hidradenoma groups separately.21 Our discussion will favor the former classification as defined by Abenoza and Ackerman.5

Poromas are classically thought to originate from poroid cells located adjacent to the luminal cells of the upper intradermal and lower intraepidermal portion of the eccrine duct.5 The other main cell type in poromas, “cuticular” cells, are considered to be luminal cell islands based on their morphologic and staining similarities to normal luminal duct cells.4

More recent immunohistochemical studies, however, suggest that poromas are derived from the basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge and lower acrosyringium.4 They differentiate toward the upper acrosyringium into larger, “cuticular” cells. The basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge merge with the adjacent epidermis.4 Because the length of this sweat duct ridge is highly variable, the initial site of tumor origination along this ridge may account for the various forms of poroid tumors.4

The histologic appearance of poroid neoplasms is due to a mixture of predominately poroid cells admixed with cuticular cells. Poroid cells are uniform, small cuboidal cells with oval to round nuclei that show ductal differentiation.4,13 They are smaller than epidermal keratinocytes and contain some glycogen.21 Cuticular cells are larger cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and pale staining nucleus.4 Necrosis en masse is a common feature of poromas, which give rise to the cystic spaces these tumors commonly display. Ductal structures are variable in number, but also commonly present in these neoplasms. Apocrine poromas, by contrast, display tubular (instead of ductal) structures that are lined by columnar cells with holocrine secretion.3 The stroma of poromas is often highly vascular, which accounts for the clinical resemblance to pyogenic granulomas.3

What primarily distinguishes the poroid group of neoplasms from one another is where the neoplastic cells are situated.13 The classic eccrine poroma displays a lobular growth pattern with a broad connection to the overlying epidermis. In hidroacanthoma simplex, the neoplastic cells are arranged in nests and contained entirely within the epidermis. Dermal duct tumors have multiple, small intradermal islands, whereas poroid hidradenomas consist of a large dermal nodule of neoplastic cells. 4,21 Clear distinction between the poroid neoplasms is difficult when examining serial sections of a single poroid neoplasm.5 The presence of 2 or 3 of these tumors in a single lesion, as is seen in our case, has been previously described.22,23 These 4 tumors, therefore, are best viewed as variants of a single benign poroid growth process, rather than distinct entities.5,13 Abenoza and Ackerman collectively refers to these tumors as poromas.5

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of poromas is broad and includes a number of malignant and benign neoplasms (Table). An acral location may help to narrow the differential. In addition, dermoscopy may support a physician’s clinical suspicion; however, many dermoscopic features of poromas are non-specific and have considerable overlap with neoplasms in the differential diagnosis.6,24 Therefore, histopathology is often necessary for diagnosis. As such, when poromas are suspected clinically, biopsy is recommended to rule out other neoplasms.

Treatment

Poromas are benign neoplasms; therefore, surgical treatment is optional.3,25 Treatment options include simple excision, therapeutic shave removal, electrodesiccation and curettage or CO2 laser removal.3,25

Some authors recommend that eccrine poromas be surgically excised due to the risk of malignant degeneration.6,7,9 As previously stated, porocarcinoma can arise de novo, but may also arise within a preexisting benign poroma.7 Treatment for porocarcinoma includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.26 Chemotherapy and/or radiation may be added if the lesion has metastasized.27 Despite surgical treatment, local reoccurrence is common (20%).27

Our Patient

The initial clinical impression in our patient favored eccrine poroma given the morphological appearance and acral location; however, other  neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

Histologic evaluation showed multiple lobules of predominately uniform cuboidal cells with a broad connection to the epidermis (Figure 2). A few larger cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and pale staining nuclei were noted within these lobules. The stroma was rather vascular; however, no necrosis en masse was found. These features were consistent with a diagnosis of eccrine poroma. Other sections demonstrated nests of predominately poroid cells contained entirely within the epidermis, as seen in hidroacanthoma simplex (Figure 3). Still additional sections showed small islands of poroid cells as seen in dermal duct tumor (Figure 4). Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up so additional treatment options could not be discussed.

Conclusion

Our case represents a typical presentation of a relatively uncommon adnexal neoplasm. As is common with poromas, our case was seen in a middle-aged adult and on an acral location.1 The clinical presentation of poromas can mimic those of many other benign and malignant tumors; therefore, biopsy is necessary in confirming the diagnosis. The histopathology of our case demonstrates features of hidroacathoma simplex, eccrine poroma and dermal duct tumor, depending on the section observed. Further immunohistochemical studies may better define and classify these lesions.

Dr. Serravallo is with Hackensack University Medical Group in Hackensack NJ.

Dr. Alapati is chief of dermatology at Brooklyn Veterans Affairs Medical Center Dermatology Service in Brooklyn, NY.

Dr. Khachemoune, the Section Editor of Derm DX, is with the Department of Dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate in Brooklyn, NY.

Disclosure: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(9):1053-1061.

2. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74(5):511-521.

3. McCalmont TH. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012:1841-1846.

4. Battistella M, Langbein L, Peltre B, Cribier B. From hidroacanthoma simplex to poroid hidradenoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemic study of poroid neoplasms and reappraisal of their histogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32(5):459-468.

5. Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Poromas. In: Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms with Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1990:113-183.

6. Sgouros D, Piana S, Argenziano G, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathological features of eccrine poroid neoplasms. Dermatology. 2013;227(2):175-179.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, May K, Motley RJ. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(1):84-86.

8. Goldner R. Eccrine poromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101(5):606-608.

9. Brown CW Jr, Dy LC. Eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(6):433-438.

10. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(6):710-720.

11. Shaw M, McKee PH, Lowe D, Black MM. Malignant eccrine poroma: a study of twenty-seven cases. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107(6):675-680.

12. Pylyser K, De Wolf-Peeters C, Marien K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167(5):243-249.

13. Casper DJ, Glass FL, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88(5):227-229.

14. Sidro-Sarto M, Guimerá-Martin-Neda F, Perez-Robayna N, et al. Eccrine poroma arising in chronic radiation dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(12):1517-1519.

15. Deckelbaum S, Touloei K, Shitabata PK, Sire DJ, Horowitz D. Eccrine poromatosis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(5):543-548.

16. Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez YE. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of a series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(2):108-118.

17. Jeon J, Kim JH, Baek YS, Kim A, Seo SH, Oh CH. Eccrine poroma and eccrine porocarcinoma in linear epidermal nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(5):430-432.

18. Guimerá Martín-Neda F, García Bustínduy M, Noda Cabrera A, Sánchez González R, García Montelongo R. A rapidly growing eccrine poroma in a pregnant woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(1):124-126.

19. Liegl B, Regauer S. Eccrine carcinoma (nodular porocarcinoma) of the vulva. Histopathology. 2005;47(3):324-326.

20. Grayson W, Loubser JS. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the penis. J Urol. 2003;169(2):611-612.

21. Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

22. Chiu HH, Lan CC, Wu CS, Cheng GS, Tsai KB, Chen PH. A single lesion showing features of pigmented eccrine poroma and poroid hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(9):861-865.

23. Kakinuma H, Miyamoto R, Iwasawa U, Babe S, Suzuki H. Three subtypes of poroid neoplasia in a single lesion: eccrine poroma, hidroacanthoma simplex, and dermal duct tumor. Histologic, histochemical, and ultrastructural findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16(1):66-72.

24. Nicolino R, Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, et al. Dermoscopy of eccrine poroma. Dermatology. 2007;215(2):160-163.

25. Mahajan RS, Parikh AA, Chhajlani NP, Bilimoria FE. Eccrine poroma on the face: an atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(1):88-90.

26. Sharathkumar HK, Hemalatha AL, Ramesh DB, Soni A, Revathi V. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(12):2966-2967.

27. Cowden A, Dans M, Giuseppe M, Junkins-Hopkins J, Van Voorhees AS. Eccrine porocarcinoma arising in two African American patients: distinct presentations both treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(2):146-150.

28. Junck M, Huerter CJ, Sarma DP. Rapidly growing hemorrhagic papule on the cheek of a 54-year-old man. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(1):11.

29. Choi YD, Chun SM, Jin SA, et al. Amelanotic acral melanomas: clinicopathological, BRAF mutation, and KIT aberration analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):700-707.

30. Giacomel J, Zalaudek I. Pink lesions. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(4):649-678.

A 57-year-old male with Fitzpatrick skin type III was referred by his primary care physician for the evaluation and management of a newly developed lesion that on exam was consistent with an acrochordon. However, during a full-body skin examination, we noted a 1.3 cm x 0.8 cm well-circumscribed light pink plaque with slight scale and no ulceration on the left medial ankle. The superior border of the lesion was slightly more elevated and small fine vessels were evident on close examination (Figures 1A and 1B). The patient had no personal family history of skin cancer. The patient had no known medical problems, took no medications and denied any trauma to the area.

The ankle lesion was not of concern to the patient, but upon questioning he reported it to have been present for several months. He was unsure if it was increasing in size and denied any symptoms such as pain, pruritus or bleeding. A biopsy using tangential shave technique of the lesion was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma with histologic features of Hidroacanthoma Simplex and Dermal Tumor in the same lesion

Aporoma is a benign neoplasm that originates from the intraepidermal portion of the sweat duct.1 Poromas were first described in 1956 in a case series of 5 patients, each of whom presented with a lesion on the foot.2 While poromas were originally described as originating from the eccrine sweat gland, some tumors are of apocrine origin.1,2 Nevertheless, the terms eccrine and poroma are commonly linked together by many dermatologists.3

Clinical Presentation

Poromas classically present as a solitary, dome shaped, red or pink papule, plaque or nodule.1 Bluish and pigmented lesions have also been described.4 They are usually solitary lesions with either a smooth, dull, shiny, scaly or verrucous surface.5,6 Erosions, ulcerations and crust may be present as a result of trauma.5 Pedunculated lesions have also been reported. 7

Poromas are most commonly acral in location, especially on the soles or sides of the foot (Figures 1A and B); however, they may occur on any cutaneous surface with eccrine or apocrine glands.6 The face and scalp are also common locations in the middle-aged and elderly.7 They are usually slow growing and asymptomatic, although pain or pruritus may be present. 1 The rare clinical variant termed eccrine poromatosis is characterized by multiple poromas in an acral or widespread distribution.3,8

Each benign poroid neoplasm also has a malignant counterpart. Porocarcinomas may arise from a preexisting poroma or de novo.6,9 The number of porocarcinomas that develop from preexisting poromas is largely unknown, as studies have produced divergent data.6 The rarity of porocarcinomas makes it difficult to quantify rates of malignant transformation; however, the presence of some lesions for 20 or more years suggests malignant degeneration from benign lesions.10,11

Eccrine porocarcinomas are typically described as firm erythematous to violaceous nodules that most commonly occur on the lower extremities.9 When transformation occurs, signs and symptoms such as spontaneous bleeding, ulceration, itching, pain and sudden growth over a short period of time may serve as potential markers.9

Epidemiology

Neoplasms of eccrine or apocrine origin are relatively uncommon. Sweat gland neoplasms represent about 1% of all primary cutaneous tumors and approximately 10% of these are eccrine poromas.12 They most commonly occur in the middle-aged to elderly population with no gender or ethnic predilection.1,13 There have been several case reports of poromas originating after long-term radiation exposure.14,15 Additionally, poromas may be found as secondary lesions arising within a nevus sebaceous or an epidermal nevus.16,17 They have also been reported in association with pregnancy.18

Eccrine porocarcinoma, on the other hand, is a rare tumor, typically found in those age 60 and older and most commonly on the lower extremities.6 The trunk, face, scalp, upper extremities, vulva and penis are other reported sites.6,19,20

Etiopathogenesis & Histopathology

The classification of poroid tumors is a somewhat confusing area in dermatopathology. In addition to eccrine poroma, there are 3 other poroid neoplasms including hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor and poroid (eccrine) hidradenoma. These benign poroid tumors comprise a family of tumors with similar architectural and cytologic features.5 As a result, some argue that these 4 tumors represent a single pathologic process rather than distinct entities.5,13 Others classify the poroid and hidradenoma groups separately.21 Our discussion will favor the former classification as defined by Abenoza and Ackerman.5

Poromas are classically thought to originate from poroid cells located adjacent to the luminal cells of the upper intradermal and lower intraepidermal portion of the eccrine duct.5 The other main cell type in poromas, “cuticular” cells, are considered to be luminal cell islands based on their morphologic and staining similarities to normal luminal duct cells.4

More recent immunohistochemical studies, however, suggest that poromas are derived from the basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge and lower acrosyringium.4 They differentiate toward the upper acrosyringium into larger, “cuticular” cells. The basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge merge with the adjacent epidermis.4 Because the length of this sweat duct ridge is highly variable, the initial site of tumor origination along this ridge may account for the various forms of poroid tumors.4

The histologic appearance of poroid neoplasms is due to a mixture of predominately poroid cells admixed with cuticular cells. Poroid cells are uniform, small cuboidal cells with oval to round nuclei that show ductal differentiation.4,13 They are smaller than epidermal keratinocytes and contain some glycogen.21 Cuticular cells are larger cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and pale staining nucleus.4 Necrosis en masse is a common feature of poromas, which give rise to the cystic spaces these tumors commonly display. Ductal structures are variable in number, but also commonly present in these neoplasms. Apocrine poromas, by contrast, display tubular (instead of ductal) structures that are lined by columnar cells with holocrine secretion.3 The stroma of poromas is often highly vascular, which accounts for the clinical resemblance to pyogenic granulomas.3

What primarily distinguishes the poroid group of neoplasms from one another is where the neoplastic cells are situated.13 The classic eccrine poroma displays a lobular growth pattern with a broad connection to the overlying epidermis. In hidroacanthoma simplex, the neoplastic cells are arranged in nests and contained entirely within the epidermis. Dermal duct tumors have multiple, small intradermal islands, whereas poroid hidradenomas consist of a large dermal nodule of neoplastic cells. 4,21 Clear distinction between the poroid neoplasms is difficult when examining serial sections of a single poroid neoplasm.5 The presence of 2 or 3 of these tumors in a single lesion, as is seen in our case, has been previously described.22,23 These 4 tumors, therefore, are best viewed as variants of a single benign poroid growth process, rather than distinct entities.5,13 Abenoza and Ackerman collectively refers to these tumors as poromas.5

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of poromas is broad and includes a number of malignant and benign neoplasms (Table). An acral location may help to narrow the differential. In addition, dermoscopy may support a physician’s clinical suspicion; however, many dermoscopic features of poromas are non-specific and have considerable overlap with neoplasms in the differential diagnosis.6,24 Therefore, histopathology is often necessary for diagnosis. As such, when poromas are suspected clinically, biopsy is recommended to rule out other neoplasms.

Treatment

Poromas are benign neoplasms; therefore, surgical treatment is optional.3,25 Treatment options include simple excision, therapeutic shave removal, electrodesiccation and curettage or CO2 laser removal.3,25

Some authors recommend that eccrine poromas be surgically excised due to the risk of malignant degeneration.6,7,9 As previously stated, porocarcinoma can arise de novo, but may also arise within a preexisting benign poroma.7 Treatment for porocarcinoma includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.26 Chemotherapy and/or radiation may be added if the lesion has metastasized.27 Despite surgical treatment, local reoccurrence is common (20%).27

Our Patient

The initial clinical impression in our patient favored eccrine poroma given the morphological appearance and acral location; however, other  neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

Histologic evaluation showed multiple lobules of predominately uniform cuboidal cells with a broad connection to the epidermis (Figure 2). A few larger cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and pale staining nuclei were noted within these lobules. The stroma was rather vascular; however, no necrosis en masse was found. These features were consistent with a diagnosis of eccrine poroma. Other sections demonstrated nests of predominately poroid cells contained entirely within the epidermis, as seen in hidroacanthoma simplex (Figure 3). Still additional sections showed small islands of poroid cells as seen in dermal duct tumor (Figure 4). Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up so additional treatment options could not be discussed.

Conclusion

Our case represents a typical presentation of a relatively uncommon adnexal neoplasm. As is common with poromas, our case was seen in a middle-aged adult and on an acral location.1 The clinical presentation of poromas can mimic those of many other benign and malignant tumors; therefore, biopsy is necessary in confirming the diagnosis. The histopathology of our case demonstrates features of hidroacathoma simplex, eccrine poroma and dermal duct tumor, depending on the section observed. Further immunohistochemical studies may better define and classify these lesions.

Dr. Serravallo is with Hackensack University Medical Group in Hackensack NJ.

Dr. Alapati is chief of dermatology at Brooklyn Veterans Affairs Medical Center Dermatology Service in Brooklyn, NY.

Dr. Khachemoune, the Section Editor of Derm DX, is with the Department of Dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate in Brooklyn, NY.

Disclosure: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(9):1053-1061.

2. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74(5):511-521.

3. McCalmont TH. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012:1841-1846.

4. Battistella M, Langbein L, Peltre B, Cribier B. From hidroacanthoma simplex to poroid hidradenoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemic study of poroid neoplasms and reappraisal of their histogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32(5):459-468.

5. Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Poromas. In: Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms with Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1990:113-183.

6. Sgouros D, Piana S, Argenziano G, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathological features of eccrine poroid neoplasms. Dermatology. 2013;227(2):175-179.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, May K, Motley RJ. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(1):84-86.

8. Goldner R. Eccrine poromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101(5):606-608.

9. Brown CW Jr, Dy LC. Eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(6):433-438.

10. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(6):710-720.

11. Shaw M, McKee PH, Lowe D, Black MM. Malignant eccrine poroma: a study of twenty-seven cases. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107(6):675-680.

12. Pylyser K, De Wolf-Peeters C, Marien K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167(5):243-249.

13. Casper DJ, Glass FL, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88(5):227-229.

14. Sidro-Sarto M, Guimerá-Martin-Neda F, Perez-Robayna N, et al. Eccrine poroma arising in chronic radiation dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(12):1517-1519.

15. Deckelbaum S, Touloei K, Shitabata PK, Sire DJ, Horowitz D. Eccrine poromatosis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(5):543-548.

16. Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez YE. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of a series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(2):108-118.

17. Jeon J, Kim JH, Baek YS, Kim A, Seo SH, Oh CH. Eccrine poroma and eccrine porocarcinoma in linear epidermal nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(5):430-432.

18. Guimerá Martín-Neda F, García Bustínduy M, Noda Cabrera A, Sánchez González R, García Montelongo R. A rapidly growing eccrine poroma in a pregnant woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(1):124-126.

19. Liegl B, Regauer S. Eccrine carcinoma (nodular porocarcinoma) of the vulva. Histopathology. 2005;47(3):324-326.

20. Grayson W, Loubser JS. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the penis. J Urol. 2003;169(2):611-612.

21. Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

22. Chiu HH, Lan CC, Wu CS, Cheng GS, Tsai KB, Chen PH. A single lesion showing features of pigmented eccrine poroma and poroid hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(9):861-865.

23. Kakinuma H, Miyamoto R, Iwasawa U, Babe S, Suzuki H. Three subtypes of poroid neoplasia in a single lesion: eccrine poroma, hidroacanthoma simplex, and dermal duct tumor. Histologic, histochemical, and ultrastructural findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16(1):66-72.

24. Nicolino R, Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, et al. Dermoscopy of eccrine poroma. Dermatology. 2007;215(2):160-163.

25. Mahajan RS, Parikh AA, Chhajlani NP, Bilimoria FE. Eccrine poroma on the face: an atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(1):88-90.

26. Sharathkumar HK, Hemalatha AL, Ramesh DB, Soni A, Revathi V. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(12):2966-2967.

27. Cowden A, Dans M, Giuseppe M, Junkins-Hopkins J, Van Voorhees AS. Eccrine porocarcinoma arising in two African American patients: distinct presentations both treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(2):146-150.

28. Junck M, Huerter CJ, Sarma DP. Rapidly growing hemorrhagic papule on the cheek of a 54-year-old man. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(1):11.

29. Choi YD, Chun SM, Jin SA, et al. Amelanotic acral melanomas: clinicopathological, BRAF mutation, and KIT aberration analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):700-707.

30. Giacomel J, Zalaudek I. Pink lesions. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(4):649-678.

Diagnosis: Eccrine Poroma with histologic features of Hidroacanthoma Simplex and Dermal Tumor in the same lesion

Aporoma is a benign neoplasm that originates from the intraepidermal portion of the sweat duct.1 Poromas were first described in 1956 in a case series of 5 patients, each of whom presented with a lesion on the foot.2 While poromas were originally described as originating from the eccrine sweat gland, some tumors are of apocrine origin.1,2 Nevertheless, the terms eccrine and poroma are commonly linked together by many dermatologists.3

Clinical Presentation

Poromas classically present as a solitary, dome shaped, red or pink papule, plaque or nodule.1 Bluish and pigmented lesions have also been described.4 They are usually solitary lesions with either a smooth, dull, shiny, scaly or verrucous surface.5,6 Erosions, ulcerations and crust may be present as a result of trauma.5 Pedunculated lesions have also been reported. 7

Poromas are most commonly acral in location, especially on the soles or sides of the foot (Figures 1A and B); however, they may occur on any cutaneous surface with eccrine or apocrine glands.6 The face and scalp are also common locations in the middle-aged and elderly.7 They are usually slow growing and asymptomatic, although pain or pruritus may be present. 1 The rare clinical variant termed eccrine poromatosis is characterized by multiple poromas in an acral or widespread distribution.3,8

Each benign poroid neoplasm also has a malignant counterpart. Porocarcinomas may arise from a preexisting poroma or de novo.6,9 The number of porocarcinomas that develop from preexisting poromas is largely unknown, as studies have produced divergent data.6 The rarity of porocarcinomas makes it difficult to quantify rates of malignant transformation; however, the presence of some lesions for 20 or more years suggests malignant degeneration from benign lesions.10,11

Eccrine porocarcinomas are typically described as firm erythematous to violaceous nodules that most commonly occur on the lower extremities.9 When transformation occurs, signs and symptoms such as spontaneous bleeding, ulceration, itching, pain and sudden growth over a short period of time may serve as potential markers.9

Epidemiology

Neoplasms of eccrine or apocrine origin are relatively uncommon. Sweat gland neoplasms represent about 1% of all primary cutaneous tumors and approximately 10% of these are eccrine poromas.12 They most commonly occur in the middle-aged to elderly population with no gender or ethnic predilection.1,13 There have been several case reports of poromas originating after long-term radiation exposure.14,15 Additionally, poromas may be found as secondary lesions arising within a nevus sebaceous or an epidermal nevus.16,17 They have also been reported in association with pregnancy.18

Eccrine porocarcinoma, on the other hand, is a rare tumor, typically found in those age 60 and older and most commonly on the lower extremities.6 The trunk, face, scalp, upper extremities, vulva and penis are other reported sites.6,19,20

Etiopathogenesis & Histopathology

The classification of poroid tumors is a somewhat confusing area in dermatopathology. In addition to eccrine poroma, there are 3 other poroid neoplasms including hidroacanthoma simplex, dermal duct tumor and poroid (eccrine) hidradenoma. These benign poroid tumors comprise a family of tumors with similar architectural and cytologic features.5 As a result, some argue that these 4 tumors represent a single pathologic process rather than distinct entities.5,13 Others classify the poroid and hidradenoma groups separately.21 Our discussion will favor the former classification as defined by Abenoza and Ackerman.5

Poromas are classically thought to originate from poroid cells located adjacent to the luminal cells of the upper intradermal and lower intraepidermal portion of the eccrine duct.5 The other main cell type in poromas, “cuticular” cells, are considered to be luminal cell islands based on their morphologic and staining similarities to normal luminal duct cells.4

More recent immunohistochemical studies, however, suggest that poromas are derived from the basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge and lower acrosyringium.4 They differentiate toward the upper acrosyringium into larger, “cuticular” cells. The basal keratinocytes of the sweat duct ridge merge with the adjacent epidermis.4 Because the length of this sweat duct ridge is highly variable, the initial site of tumor origination along this ridge may account for the various forms of poroid tumors.4

The histologic appearance of poroid neoplasms is due to a mixture of predominately poroid cells admixed with cuticular cells. Poroid cells are uniform, small cuboidal cells with oval to round nuclei that show ductal differentiation.4,13 They are smaller than epidermal keratinocytes and contain some glycogen.21 Cuticular cells are larger cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and pale staining nucleus.4 Necrosis en masse is a common feature of poromas, which give rise to the cystic spaces these tumors commonly display. Ductal structures are variable in number, but also commonly present in these neoplasms. Apocrine poromas, by contrast, display tubular (instead of ductal) structures that are lined by columnar cells with holocrine secretion.3 The stroma of poromas is often highly vascular, which accounts for the clinical resemblance to pyogenic granulomas.3

What primarily distinguishes the poroid group of neoplasms from one another is where the neoplastic cells are situated.13 The classic eccrine poroma displays a lobular growth pattern with a broad connection to the overlying epidermis. In hidroacanthoma simplex, the neoplastic cells are arranged in nests and contained entirely within the epidermis. Dermal duct tumors have multiple, small intradermal islands, whereas poroid hidradenomas consist of a large dermal nodule of neoplastic cells. 4,21 Clear distinction between the poroid neoplasms is difficult when examining serial sections of a single poroid neoplasm.5 The presence of 2 or 3 of these tumors in a single lesion, as is seen in our case, has been previously described.22,23 These 4 tumors, therefore, are best viewed as variants of a single benign poroid growth process, rather than distinct entities.5,13 Abenoza and Ackerman collectively refers to these tumors as poromas.5

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of poromas is broad and includes a number of malignant and benign neoplasms (Table). An acral location may help to narrow the differential. In addition, dermoscopy may support a physician’s clinical suspicion; however, many dermoscopic features of poromas are non-specific and have considerable overlap with neoplasms in the differential diagnosis.6,24 Therefore, histopathology is often necessary for diagnosis. As such, when poromas are suspected clinically, biopsy is recommended to rule out other neoplasms.

Treatment

Poromas are benign neoplasms; therefore, surgical treatment is optional.3,25 Treatment options include simple excision, therapeutic shave removal, electrodesiccation and curettage or CO2 laser removal.3,25

Some authors recommend that eccrine poromas be surgically excised due to the risk of malignant degeneration.6,7,9 As previously stated, porocarcinoma can arise de novo, but may also arise within a preexisting benign poroma.7 Treatment for porocarcinoma includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.26 Chemotherapy and/or radiation may be added if the lesion has metastasized.27 Despite surgical treatment, local reoccurrence is common (20%).27

Our Patient

The initial clinical impression in our patient favored eccrine poroma given the morphological appearance and acral location; however, other  neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

Histologic evaluation showed multiple lobules of predominately uniform cuboidal cells with a broad connection to the epidermis (Figure 2). A few larger cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm and pale staining nuclei were noted within these lobules. The stroma was rather vascular; however, no necrosis en masse was found. These features were consistent with a diagnosis of eccrine poroma. Other sections demonstrated nests of predominately poroid cells contained entirely within the epidermis, as seen in hidroacanthoma simplex (Figure 3). Still additional sections showed small islands of poroid cells as seen in dermal duct tumor (Figure 4). Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up so additional treatment options could not be discussed.

Conclusion

Our case represents a typical presentation of a relatively uncommon adnexal neoplasm. As is common with poromas, our case was seen in a middle-aged adult and on an acral location.1 The clinical presentation of poromas can mimic those of many other benign and malignant tumors; therefore, biopsy is necessary in confirming the diagnosis. The histopathology of our case demonstrates features of hidroacathoma simplex, eccrine poroma and dermal duct tumor, depending on the section observed. Further immunohistochemical studies may better define and classify these lesions.

Dr. Serravallo is with Hackensack University Medical Group in Hackensack NJ.

Dr. Alapati is chief of dermatology at Brooklyn Veterans Affairs Medical Center Dermatology Service in Brooklyn, NY.

Dr. Khachemoune, the Section Editor of Derm DX, is with the Department of Dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate in Brooklyn, NY.

Disclosure: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(9):1053-1061.

2. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74(5):511-521.

3. McCalmont TH. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012:1841-1846.

4. Battistella M, Langbein L, Peltre B, Cribier B. From hidroacanthoma simplex to poroid hidradenoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemic study of poroid neoplasms and reappraisal of their histogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32(5):459-468.

5. Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Poromas. In: Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms with Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1990:113-183.

6. Sgouros D, Piana S, Argenziano G, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathological features of eccrine poroid neoplasms. Dermatology. 2013;227(2):175-179.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, May K, Motley RJ. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(1):84-86.

8. Goldner R. Eccrine poromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101(5):606-608.

9. Brown CW Jr, Dy LC. Eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(6):433-438.

10. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(6):710-720.

11. Shaw M, McKee PH, Lowe D, Black MM. Malignant eccrine poroma: a study of twenty-seven cases. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107(6):675-680.

12. Pylyser K, De Wolf-Peeters C, Marien K. The histology of eccrine poromas: a study of 14 cases. Dermatologica. 1983;167(5):243-249.

13. Casper DJ, Glass FL, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88(5):227-229.

14. Sidro-Sarto M, Guimerá-Martin-Neda F, Perez-Robayna N, et al. Eccrine poroma arising in chronic radiation dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(12):1517-1519.

15. Deckelbaum S, Touloei K, Shitabata PK, Sire DJ, Horowitz D. Eccrine poromatosis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(5):543-548.

16. Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez YE. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of a series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(2):108-118.

17. Jeon J, Kim JH, Baek YS, Kim A, Seo SH, Oh CH. Eccrine poroma and eccrine porocarcinoma in linear epidermal nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(5):430-432.

18. Guimerá Martín-Neda F, García Bustínduy M, Noda Cabrera A, Sánchez González R, García Montelongo R. A rapidly growing eccrine poroma in a pregnant woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(1):124-126.

19. Liegl B, Regauer S. Eccrine carcinoma (nodular porocarcinoma) of the vulva. Histopathology. 2005;47(3):324-326.

20. Grayson W, Loubser JS. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the penis. J Urol. 2003;169(2):611-612.

21. Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

22. Chiu HH, Lan CC, Wu CS, Cheng GS, Tsai KB, Chen PH. A single lesion showing features of pigmented eccrine poroma and poroid hidradenoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(9):861-865.

23. Kakinuma H, Miyamoto R, Iwasawa U, Babe S, Suzuki H. Three subtypes of poroid neoplasia in a single lesion: eccrine poroma, hidroacanthoma simplex, and dermal duct tumor. Histologic, histochemical, and ultrastructural findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16(1):66-72.

24. Nicolino R, Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, et al. Dermoscopy of eccrine poroma. Dermatology. 2007;215(2):160-163.

25. Mahajan RS, Parikh AA, Chhajlani NP, Bilimoria FE. Eccrine poroma on the face: an atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(1):88-90.

26. Sharathkumar HK, Hemalatha AL, Ramesh DB, Soni A, Revathi V. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(12):2966-2967.

27. Cowden A, Dans M, Giuseppe M, Junkins-Hopkins J, Van Voorhees AS. Eccrine porocarcinoma arising in two African American patients: distinct presentations both treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(2):146-150.

28. Junck M, Huerter CJ, Sarma DP. Rapidly growing hemorrhagic papule on the cheek of a 54-year-old man. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(1):11.

29. Choi YD, Chun SM, Jin SA, et al. Amelanotic acral melanomas: clinicopathological, BRAF mutation, and KIT aberration analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):700-707.

30. Giacomel J, Zalaudek I. Pink lesions. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(4):649-678.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.

neoplasms, including amelanotic melanoma, could not be ruled out. A biopsy of the lesion was, therefore, performed.