When First Ray Surgery Fails

Complications of first ray surgery range from non-union to osteomyelitis. These authors provide a guide to preventing and revising failures in first ray surgery, emphasizing preoperative planning and sound surgical principles for revision techniques.

Postoperative complications of first ray surgery are inevitable due to the sheer volume of procedures performed by foot and ankle surgeons. Some of the most common first ray complications include non-unions, malunions, avascular necrosis and infection.

Postoperative complications of first ray surgery are inevitable due to the sheer volume of procedures performed by foot and ankle surgeons. Some of the most common first ray complications include non-unions, malunions, avascular necrosis and infection.

When patients present with these complications, precise clinical evaluations, diagnostic imaging and procedural algorithms become paramount for a timely diagnosis and implementation of effective treatments for each specific issue. Often, when we face a forefoot surgery complication, revision is warranted for optimal correction and patient outcomes.

All surgeries have a possibility of complication but certain procedures in the forefoot tend to have more risks than others. Lagaay and colleagues reported complication rates in common first ray procedures that later require further revision or fusion.1 They found complication rates of 5.56, 8.19 and 8.82 percent in 270 chevron osteotomy, Lapidus and closing base wedge osteotomy procedures respectively.

Accordingly, we will highlight common obstacles with first ray surgery and practical methods of management.

Understanding Non-Union And Optimizing Outcomes

Understanding Non-Union And Optimizing Outcomes

When evaluating a patient with a potential first ray non-union, it is important to identify the etiology prior to immediately revising the surgery in the operative suite. Many times, the lymphatic architecture needs time to defervesce in order to limit postoperative chronic edema and stiffness.

Surgeons should take note of the patient’s full medical history as many risks for potential complications often go overlooked during the initial preoperative evaluation. Underlying risk factors include immunosuppression/susceptibility to chronic infection, impaired vascularity, poor bone quality, vitamin D deficiency, systemic/metabolic disease (diabetes) and lifestyle habits causing delayed healing. Chen and colleagues noted that obesity increased the risk of repeat surgery and patients who smoke increase their complication rates by 36.8 percent.2,3 Donigan and coworkers also concluded in a rat study model that even the use of nicotine patches caused an increased time to union with decreased torque failure and stiffness apparent on mechanical testing.4

Many factors may be non-modifiable but a thorough laboratory workup may assist the provider in developing treatment strategies to promote successful fusion. Commonly, providers should investigate vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D/25(OH)D) levels in the perioperative setting (normal value of 30 ng/mL or 75 nmol/L).

However, ensuring metabolic optimization should not end there. Patients also need adequate levels of C-terminal telopeptide (>300 pg/mL), intact parathyroid hormone (1055 pg/mL) and calcium. C-terminal telopeptide is an indirect measure of metabolic activity though osteoclastic activity/bone turnover and can gauge the potential response to medical treatment such as teriparatide (Forteo, Lilly). If patients appear to have a low vitamin D level, proper daily/weekly supplementation is warranted. Consultation with endocrinology and/or bone metabolic specialists can often assist the surgeon in reaching these benchmarks for success through pharmacologic supplementation.

Some postoperative medications can negatively impact healing. We know that inhibition of prostaglandins has a negative effect on endochondral ossification. Previous studies in a rat femur model have shown that the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) delays callus formation and osseous healing.5 Giannoudis and colleagues showed an association of NSAIDs with non-union that was worse than that of smoking.6 Based on available literature, it appears safe to use NSAIDs in the short term for approximately seven to 10 days postoperatively.6

Some postoperative medications can negatively impact healing. We know that inhibition of prostaglandins has a negative effect on endochondral ossification. Previous studies in a rat femur model have shown that the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) delays callus formation and osseous healing.5 Giannoudis and colleagues showed an association of NSAIDs with non-union that was worse than that of smoking.6 Based on available literature, it appears safe to use NSAIDs in the short term for approximately seven to 10 days postoperatively.6

In addition to host factors, postoperative non-union, surgical technique and procedure selection have a substantial impact on complications versus success. Non-union rates in first ray surgery are not uncommon but certain procedures have a greater propensity than others. Lapidus non-union rates can range from 3.3 to 12 percent and first metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) arthrodesis has non-union rates ranging from 2 to 23 percent.7–10 Interphalangeal joint arthrodesis also has a 13.8 percent failure of radiographic non-union, according to Thorud and coworkers, who noted this was likely due to the biconcave distal phalangeal joint and the need for meticulous joint preparation.11 Bennet, Sharma and their respective colleagues have published positive results regarding first MPJ fusion (98.7 and 97.1 percent respectively).12,13

The variation in results with respect to first MPJ and Lapidus arthrodesis could be attributed to the surgical technique of joint preparation and fixation, which plays a major role in the success of these cases. It is important to recognize the scalloped nature of the subchondral bone plate and that low energy joint preparation by means of curettes and osteotomes rather than saw blade and burr is preferred as thermal necrosis can occur and decrease the chance of successful union.14

With respect to the Lapidus procedure, Barp and coworkers noted increased successful unions when using intraplate and dorsal medial plate fixation in combination with lag screw fixation in comparison to fixation with two crossed lag screws.15 These findings are consistent across the literature yet one can still achieve successful union through sound principles and two-screw fixation.

With respect to hallux valgus correction, surgeons must follow basic tenets with respect to fixation and create a stable osteotomy site to withstand the ground reaction force vector. Adhering to these principles is paramount to avoid bending and shearing moments that can lead to non-union.16 Additionally, deliberate soft tissue dissection will allow for preservation of the periosteum and periarticular vascularity, resulting in a greater chance for successful union.17–19

Interestingly, the literature by Kuhn and colleagues has demonstrated a reduction in laser Doppler flow to the first metatarsal subsequent to capsulotomy, sequential lateral release and osteotomy.19 However, their study noted no evidence of avascular necrosis. Furthermore, despite circulatory disturbance being inevitable, authors have noted that this is not clinically significant due to the postoperative perforator and microvascular adaptation.20

Essential Keys To Revisional Surgery For Non-Unions In The First Ray

With respect to hallux rigidus, adequate joint preparation and revising a non-union will often lead to a shortened first metatarsal and imbalance of the forefoot metatarsal parabola. Incorporation of an interpositional structural allograft or autograft at the arthrodesis site provide useful modalities with comparable rates of success in comparison to distraction osteogenesis. Utilization of autogenous bone graft in comparison with allogeneic bone graft is a subject of frequent debate. Studies have supported the use of adjunctive bone marrow aspirate concentrate and allograft with a comparable rate of osseous union.14

In the event one encounters a non-union as a complication, consider the incorporation of bone stimulators in the revisional process. Alternatively, one can distract through a hypertrophic non-union, which researchers have demonstrated in the tibia to be successful, allowing for a physiologic increase in local perfusion (three to 10 times) and stimulation of regenerated bone formation.21

The debate over which type of bone stimulator to use is often a drawback to the treatment plan. As is the case with many options, surgeons often resort to familiarity versus a bone stimulator that would benefit the patient the most and have the best adherence. Implantable bone stimulators with direct current clearly have the best adherence in use in comparison to other options. Hughes and colleagues found 85 percent healing of all osteotomies in their study after 7.1 months, suggesting implantable bone stimulators are superior to other modalities such as ultrasound, pulsed electromagnetic field and capacitive coupling.22

The debate over which type of bone stimulator to use is often a drawback to the treatment plan. As is the case with many options, surgeons often resort to familiarity versus a bone stimulator that would benefit the patient the most and have the best adherence. Implantable bone stimulators with direct current clearly have the best adherence in use in comparison to other options. Hughes and colleagues found 85 percent healing of all osteotomies in their study after 7.1 months, suggesting implantable bone stimulators are superior to other modalities such as ultrasound, pulsed electromagnetic field and capacitive coupling.22

While implantable bone stimulators have shown great success, they also come with further complications such as nerve palsy, device malfunction and infection. External/non-implantable bone stimulators are the safer option but are subject to adherence issues. While biologically plausible, low intensity pulsed ultrasound had no significant effect on bone healing in a tibial shaft model in comparison to sham in a study by Busse and colleagues.23

Preventing And Treating Postoperative Infections In The First Ray

Postoperative infections in the first ray are not uncommon but preoperative protocols and prevention strategies can often help avoid infection. As we already mentioned, in avoiding non-unions, a patient’s medical comorbidities may play a major role in surgical outcome and risks. Certain patients are more prone to developing infections than others, especially in the operative setting. Elderly patients over the age of 60, active tobacco users, patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy and/or a hemoglobin A1c of greater than 8%, patients with an active ulceration, and patients with peripheral arterial disease have a greater likelihood of developing a postoperative infection.24,25

Strict perioperative procedures and infection control guidelines have proven to reduce the rate of infection by 50 percent when surgeons follow them correctly.26 Operating rooms should reduce unnecessary traffic into the room while sterile and should have laminar air flow (as opposed to turbulent air flow) to reduce contamination in the sterile field. Patients should receive prophylactic antibiotics preoperatively with adequate sterile prep including chlorhexidine as this can reduce the bacterial load. Double preparation may be warranted in some surgical centers, especially when dealing with foot surgery as web spaces and reused tourniquets have proven to be hosts for microbial flora such as Gram positive cocci, Corynebacteria, dermatophytes and Candida.27 Also, increased tourniquet time greater than 90 minutes may be associated with postoperative infections.24

Addressing Osteomyelitis Of The First Ray

Addressing Osteomyelitis Of The First Ray

Upon presentation, understanding the degree of osteomyelitis infection is paramount in determining treatment options. Despite the practice of taking wound cultures during the initial encounter, research has shown that superficial wound cultures have a poor concordance (22 percent overall) with the pathogens causing the infection.28 Open wounds that probe to bone are more susceptible to infection in comparison to wounds that do not probe to bone.29,30

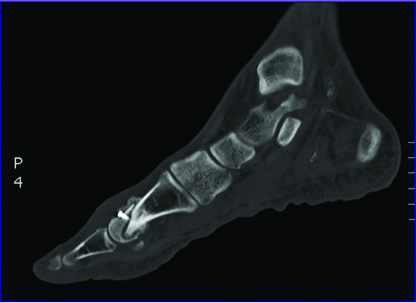

However, one should also utilize imaging modalities to confirm osteomyelitis. While magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and plain film radiographs are highly sensitive for osteomyelitis, they lack specificity.31 Studies such as Indium-111 and positron emission tomography-fludeoxyglucose-computed tomography (PET-FDG-CT) scans both have a 90 percent sensitivity and specificity in differentiating between marrow edema versus osteomyelitis.31 The clinical suspicion of osteomyelitis warrants the use of bone biopsy as part of the diagnostic armamentarium for determining the presence of active infection. These tools, along with measurement of inflammatory markers and labs, will help distinguish the level of infection and assist in preoperative surgical planning.

When There Is Bone Infection And Exposed Hardware

The stability, location and duration of hardware exposure are important when considering a salvage procedure. If one is leaving hardware intact, deep cultures must be clean prior to closure. A culture of just skin flora leads to a salvage rate of 60 percent and an improved prognosis if the infection has been present for less than two weeks.32

However, in the presence of osteomyelitis and deep fascial extension, authors have recommended guidelines for definitive hardware removal.33 For infection in stable osseous constructs with healed osteotomy sites and intact hardware, guidelines recommend hardware removal. One must accompany hardware removal with thorough osseous debridement of any infected bone and control of the dead space with antibiotic beads/spacers. When there is bone infection in the setting of a stable surgical site with delayed union, surgeons may choose to treat the pathogen and keep hardware intact. Unstable osseous constructs with hardware require staged reconstruction procedures with hardware removal and definitive fixation at a later interval.

We recommend the incorporation of antibiotic-impregnated cement, which is typically non-biodegradable although we have used calcium sulfate antibiotic beads as well. One must be aware that following antibiotic elution, the calcium sulfate beads resorb and form a fibrous granulation tissue rather than a vascular pseudomembrane.

Pertinent Considerations With First Ray Amputation

In the event of imaging studies and clinical observation resulting in a diagnosis of osteomyelitis, there is a debate between the options of salvage versus amputation. Salvage procedures often cause loss of function while hallux amputations often result in the second MPJ drifting in the sagittal and transverse planes.34,35 In a study of 50 patients, 48 patients who had an initial partial first ray amputation eventually progressed to a transmetatarsal level amputation.36

In the event of imaging studies and clinical observation resulting in a diagnosis of osteomyelitis, there is a debate between the options of salvage versus amputation. Salvage procedures often cause loss of function while hallux amputations often result in the second MPJ drifting in the sagittal and transverse planes.34,35 In a study of 50 patients, 48 patients who had an initial partial first ray amputation eventually progressed to a transmetatarsal level amputation.36

The overall instability of the partial first ray amputation can lead to revision procedures and more proximal level amputations.34-36 It is important to note the anatomic tethering of the flexor hallucis longus tendon with the flexor digitorum longus tendon at the master knot of Henry, which will cause an overpowering pull onto the flexor digitorum longus tendon and further precipitate digital contracture and medial deviation due to its oblique pull. We recommend percutaneous flexor tenotomies in this case.

Managing Segmental Bone Defects

When an osseous defect exceeds the threshold for autogenous grafts (approximately 2 cm), surgeons can institute other forms of surgical management. Vascularized bone grafting, distraction osteogenesis and use of the Masquelet technique are all great surgical options.37–42 Unfortunately, with respect to the first ray, many of these published reports are with case reports and small case series so the durability of these more sophisticated approaches requires further research.

Bone transport/distraction osteogenesis is another modality that one can utilize for non-union, avascular necrosis or segmental bone loss from infection. In Mather’s study, 15.8 weeks were required to achieve 93.8 percent length and consolidation of the second metatarsal.43 Benson and coworkers showed results averaging 20.2 mm in length of callus distraction when using bone transport.41

Bone transport/distraction osteogenesis is another modality that one can utilize for non-union, avascular necrosis or segmental bone loss from infection. In Mather’s study, 15.8 weeks were required to achieve 93.8 percent length and consolidation of the second metatarsal.43 Benson and coworkers showed results averaging 20.2 mm in length of callus distraction when using bone transport.41

While the technique and use of bone transport can provide success while keeping the first ray out to an appropriate length, one must be mindful of the soft tissue envelope and the lack of intrinsic musculature when performing this procedure. It is also important to base the vector of transport to the distal pins and lengthen parallel to the ground to avoid metatarsus primus equinus. We recommend preserving the metatarsal parabola (approximately 142 degrees with the first metatarsal equal to the third metatarsal). Consider bone transport procedures in two stages on the first metatarsal due to the likely requirement to fuse the distal regenerate bone with the base of the proximal phalanx. In keeping with principles of bone transport and tibialization of the fibula, one can also perform gradual transverse medialization of the second metatarsal and docking with the medial cuneiform and proximal phalanx successfully. Authors have described fibular bone hypertrophy occurring over the course of five years and it is therefore plausible for the second metatarsal to hypertrophy as well.44,45

Use of the Masquelet technique for reconstruction following antibiotic spacer placement has proven to be successful in previous cases.46 In the original description of the technique for segmental defects of the tibia, Masquelet and coworkers managed segmental defects ranging from 4 to 15 cm by utilizing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1) and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP2) to improve vascularity and decrease the area of resorption.

Surgical pearls for the Masquelet technique include at least 2 cm of curettage of both ends and clearing of the medullary canals for future autograft or allograft placement. Once the induced pseudomembrane has formed around the antibiotic spacer, one can use a 3:1 ratio of autograft to allograft. Finally, note that the growth factor influence and vascularity of the induced membrane are nearly depleted after six weeks.46

In Conclusion

Particularly with the volume that the majority of foot and ankle surgeons perform first ray procedures, complications can result regardless of the procedure. Fortunately, surgeons can avoid some issues through effective preoperative planning. If one is facing an obstacle postoperatively, techniques based on sound surgical principles can offer successful outcomes during revision. Metabolic optimization and patient selection are paramount in preoperative planning, and when surgeons combine these principles with effective protocols for preventing postoperative infection, the literature has shown a significant reduction in complications.

Dr. Mayer is a second-year resident with the Veterans Affairs Maryland Health Care System and the Rubin Institute for Advanced Orthopaedics at the Sinai Hospital of Baltimore.

Dr. Wynes is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Orthopaedics at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. He is a Fellow of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons.

References

- Lagaay PM, Hamilton GA, Ford LA, et al. Rates of revision surgery using chevron-Austin osteotomy, Lapidus arthrodesis, and closing base wedge osteotomy for correction of hallux valgus deformity. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2008; 47(4):267-72.

- Chen JY, Lee MJ, Rikhraj K, et al. Effect of obesity on outcome of hallux valgus surgery. Foot Ankle Int. 2015; 36(9):1078-83.

- Bettin CC, Gower K, McCormick K, et al. Cigarette smoking increases complication rate in forefoot surgery. Foot Ankle Int. 2015; 36(5):488-93.

- Donigan JA, Fredericks DC, Nepola JV, Smucker JD. The effect of transdermal nicotine on fracture healing in a rabbit model. J Orthop Trauma. 2012; 26(12):724-27.

- Altman RD, Latta LL, Keer R, et al. Effect of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on fracture healing: a laboratory study in rats. J Orthop Trauma. 1995; 9(5):392-400.

- Giannoudis PV, MacDonald DA, Matthews SJ, et al. Nonunion of the femoral diaphysis. The influence of reaming and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000; 82(5):655-58.

- Patel S, Ford LA, Etcheverry J, et al. Modified lapidus arthrodesis: rate of nonunion in 227 cases. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2004; 43(1):37-42.

- Goucher NR, Coughlin MJ. Hallux metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis using dome-shaped reamers and dorsal plate fixation: a prospective study. Foot Ankle Int. 2006; 27(11):869-76.

- Kumar S, Pradhan R, Rosenfeld PF. First metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis using a dorsal plate and a compression screw. Foot Ankle Int. 2010; 31(9):797-801.

- Roukis TS. Nonunion after arthrodesis of the first metatarsal-phalangeal joint: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011; 50(6):710-13.

- Thorud JC, Jolley T, Shibuya N, et al. Comparison of hallux interphalangeal joint arthrodesis fixation techniques: a retrospective multicenter study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016; 55(1):22-27.

- Bennett GL, Sabetta J. First metatarsalphalangeal joint arthrodesis: evaluation of plate and screw fixation. Foot Ankle Int. 2009; 30(8):752-57.

- Sharma H, Bhagat S, Deleeuw J, Denolf F. In vivo comparison of screw versus plate and screw fixation for first metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis: does augmentation of internal compression screw fixation using a semi-tubular plate shorten time to clinical and radiologic fusion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ)? Foot Ankle Surg. 2008; 47(1):2-7.

- Johnson JT, Schuberth JM, Thornton SD, Christensen JC. Joint curettage arthrodesis technique in the foot: a histological analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009; 48(5):558-64.

- Barp EA, Erickson JG, Smith HL, et al. Evaluation of fixation techniques for metatarsocuneiform arthrodesis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017; 56(3):468-73.

- DeFronzo RA, Bonadonna RC, Ferrannini E. Pathogenesis of NIDDM. A balanced overview. Diabetes Care. 1992; 15(3):318-68.

- Jones KJ, Feiwell LA, Freedman EL, Cracchiolo A 3d. The effect of chevron osteotomy with lateral capsular release on the blood supply to the first metatarsal head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995; 77(2):197–204.

- Malal JJ, Shaw-Dunn J, Kumar CS. Blood supply to the first metatarsal head and vessels at risk with a chevron osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007; 89(9):2018-22.

- Kuhn MA, Lippert FG 3rd, Phipps MJ, Williams C. Blood flow to the metatarsal head after chevron bunionectomy. Foot Ankle Int. 2005; 26(7):526-29.

- Shariff R, Attar F, Osarumwene D, et al. The risk of avascular necrosis following chevron osteotomy: a prospective study using bone scintigraphy. Acta Orthopedica Belgica. 2009; 75(2):234-38.

- Rozbruch SR, Pugsley JS, Fragomen AT, Ilizarov S.. Repair of tibial nonunions and bone defects with the Taylor spatial frame. J Orthop Trauma. 2008; 22(2):88-95.

- Hughes MS, Anglen JO. The use of implantable bone stimulators in nonunion treatment. Orthopedics. 2010; 33(3):.

- Busse JW, Bhandari M, Einhorn TA, et al. Re-evaluation of low intensity pulsed ultrasound in treatment of tibial fractures (TRUST): randomized clinical trial. Br Med J. 2016; 25:355.

- Wiewiorski M, Yasui T, Miska M, et al. Solid bolt fixation of the medial column in Charcot midfoot arthropathy. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2013; 52(1):88-94.

- Wukich DK, Crim BE, Frykberg RG, Rosario BL. et al. Neuropathy and poorly controlled diabetes increase the rate of surgical site infection after foot and ankle surgery. J Bone Joint Surgery Am. 2014; 96(10):832-39.

- Ralte P, Molloy A, Simmons D, Butcher C. The effect of strict infection control policies on the rate of infection after elective foot and ankle surgery. Bone Joint J. 2015; 97-B(4):516-9.

- Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo R, Losa Iglesias ME, Alou Cervera L, et al. Preoperative skin and nail preparation of the foot: comparison of the efficacy of 4 different methods in reducing bacterial load. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009; 61(6):986-92.

- Senneville E, Melliez H, Beltrand E, et al. Culture of percutaneous bone biopsy specimens for diagnosis of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: concordance with ulcer swab cultures. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 42(1):57-62.

- Grayson ML, Gibbons GW, Balogh K, et al. Probing to bone in infected pedal ulcers. A clinical sign of underlying osteomyelitis in diabetic patients. J Am Med Assoc. 1995; 273(1):721-30.

- Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Peters EJ, Lipsky BA. Probe-to-bone test for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis: reliable or relic? Diabetes Care. 2007; 30(2):270-74.

- Termaat MF, Raijmakers PG, Scholten HJ, et al. The accuracy of diagnostic imaging for the assessment of chronic osteomyelitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surgery Am. 2005; 87(11):2464-71.

- Viol A, Pradka SP, Baumeister SP, et al. Soft-tissue defects and exposed hardware: a review of indications for soft-tissue reconstruction and hardware preservation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 123(4):1256-63.

- Rao N, Ziran BH, Lipsky BA. Treating osteomyelitis: antibiotics and surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 27:177-87.

- Sammarco JV. Surgery of the hallux. Foot Ankle Clin. 2005; 10(1):11-12.

- Poppen NK, Mann RA, O’Konski M, Buncke HJ. Amputation of the great toe. Foot Ankle. 1981; 1(6):333-37.

- Kadukammakal J, Yau S, Urbas W. Assessment of partial first-ray resections and their tendency to progress to transmetatarsal amputations. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2012; 102(5).

- Bhosale A, Munoruth A, Blundell C, et al. Complex primary arthrodesis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint after bone loss. Foot Ankle Int. 2011; 32(10):968-72.

- Unal MB, Seker A, Demiralp B, et al. Reconstruction of traumatic composite tissue defect of medial longitudinal arch with free osteocutaneous fibular graft. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016; 55(2):333-37.

- Hwang SM, Song JK, Kim HT. Metatarsal lengthening by callotasis in adults with first brachymetatarsia. Foot Ankle Int. 2012; 33(12):1103-7.

- Lee KB, Park HW, Chung JY, et al. Comparison of the outcomes of distraction osteogenesis for first and fourth brachymetatarsia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010; 92(16):2709-18.

- Benson CJ, Banks AS. First metatarsal callus distraction. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008; 98(1):51-60.

- Makridis K, Theocharakis S, Fragkakis EM, Giannoudis PV. Reconstruction of an extensive soft tissue and bone defect of the first metatarsal with the use of Masquelet technique: A case report. Foot Ankle Surg. 2014; 20(2):19-22.

- Mather R 3d. First metatarsal lengthening. Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 2008; 7(1):25-30.

- Keating JF, Simpson AH, Robinson CM. The management of fractures with bone loss. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005; 87(2):142-50.

- Puri A, Gulia A, Chan WH. Functional and oncologic outcomes after excision of the total femur in primary bone tumors: Results with a low cost total femur prosthesis. Indian J Orthopedics. 2012; 46(4):470-74.

- Masquelet AC, Fitoussi F, Begue T, Muller GP. Reconstruction of the long bones by the induced membrane and spongy autograft. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2000; 45(3):346-53.