A Practical Approach To Surgical Management Of Charcot Foot

Despite its existence in the medical literature since 1703, Charcot neuroarthropathy remains an elusive pathology that carries the innate potential to progress and threaten efforts for successful limb salvage. Through sound evidence-based principles, treatment can be effective in temporizing the acute presentation with conservative therapy and maintaining the correction through surgical intervention.

Despite its existence in the medical literature since 1703, Charcot neuroarthropathy remains an elusive pathology that carries the innate potential to progress and threaten efforts for successful limb salvage. Through sound evidence-based principles, treatment can be effective in temporizing the acute presentation with conservative therapy and maintaining the correction through surgical intervention.

Understanding the disease progression of Charcot in the perioperative setting and determining when operative intervention would benefit the patient are challenging decisions, even for the skilled foot and ankle physician. Research has shown patients without diabetes have greater than 80 percent success with surgical reconstruction.1 Patients with a diabetic Charcot deformity and ulceration are at a 12 times increased risk of requiring an amputation for treatment in comparison to patients with diabetic foot ulcers in the absence of a Charcot deformity.2

Meanwhile, 40 percent of patients who present with radiographic or clinical signs of Charcot will have a concurrent ulceration with their Charcot deformity. The clinical significance of early recognition and appropriate management in this specific subset of patients (deformity and an ulceration) is paramount as they have a 35 percent higher mortality rate within five years in comparison to the general diabetic population.2,3

A Guide To Charcot Classification And Imaging

In 1966, Eichenholz published a classification for Charcot based on plain film X-rays, which despite advances in imaging, is still in use today.4 In regard to other classification systems, Schon, Sanders, Brosky and their respective colleagues designed systems to assist the clinician in describing the various locations of Charcot neuroarthropathy by highlighting the areas of joint destruction.5-7 Few classifications are prognostic and each alone is not comprehensive as patients with Charcot can have other areas of deformity. For instance, less than 10 percent of Charcot is isolated to the subtalar joint despite the most common appearance at the level of the tarsometatarsal joint and literature reports of metatarsophalangeal joint and even interphalangeal joint involvement.5-7 Additionally, researchers have pointed to the fact that the more proximal involvement a patient has, the greater the risks for deformity and ulceration.8,9

Plain film radiographic evaluation reveals capsular distension and fragmentation that will typically progress through the Eichenholz stages (acute, coalescing and remodeling). Advanced imaging may be necessary when there is the goal of differentiating Charcot from other pathologic processes such as infection, osteoarthritis, and stress fracture. In our experience, if more than one adjacent bone is involved on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), one should suspect Charcot neuroarthropathy. Further correlation with computed tomography (CT) can support preoperative planning and elucidation of specific joint involvement. Surgical reconstruction should ideally occur outside of the acute phase as there is an overabundance of inflammatory mediators and cytokines.10 These include tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1 and interleukin 6, which even further promote bone resorption, fragmentation and soft tissue edema.10

Is The Patient A Viable Surgical Candidate?

Operative intervention is warranted once the patient with Charcot is medically optimized and the patient has graduated from the acute phase of the deformity. Additionally, other indications include instability, chronic ulceration, infection/osteomyelitis and/or malalignment and deformity. It is important to recognize patients in the acute phase of Charcot as their presentation will often mimic a lower extremity infection, deep venous thrombophlebitis, septic joint, cellulitis, etc. Commonly, patients with Charcot present with unilateral erythema, edema and a clinically appreciable increased temperature gradient in comparison to the contralateral extremity.11

Conservative management may include aggressive immobilization and adjunctive use of bisphosphonates in order to temporize the extremity and prepare for surgical reconstruction. Non-operative management can lead to a low amputation rate of only 2.7 percent but has an ulcer recurrence rate of up to 49 percent.2,13 In a systematic review of surgical interventions for Charcot deformity, most studies were of level IV or V clinical evidence and the results were inconclusive with respect to the timing of surgery and fixation constructs.14

Conservative management may include aggressive immobilization and adjunctive use of bisphosphonates in order to temporize the extremity and prepare for surgical reconstruction. Non-operative management can lead to a low amputation rate of only 2.7 percent but has an ulcer recurrence rate of up to 49 percent.2,13 In a systematic review of surgical interventions for Charcot deformity, most studies were of level IV or V clinical evidence and the results were inconclusive with respect to the timing of surgery and fixation constructs.14

It is important to note that despite presenting with Charcot, regardless of the degree of osseous dissolution, instability or deformity, the patient may not be an optimal surgical candidate.

Pinzur demonstrated that patients are immunocompromised if they have a combination of two or more of the following: substantial bone deformity, ulcer over the infected area, osteopenia and/or obesity.15 Interestingly, in a study comparing the overall 12-month cost of below-the-knee amputation versus Charcot reconstruction, researchers found that it made financial sense to attempt limb salvage based on patient willingness, appropriate post-op characteristics and overall capability to follow perioperative instructions.16

Managing Charcot In The Perioperative Setting

Understanding the perioperative evaluation and potential sequelae of each patient’s associated comorbidities is critical for the success of reconstruction. Cognitively, the diabetic population is also at risk for subclinical albuminuria, which researchers have correlated with gray matter atrophy.17,18 Patients with diabetes may exhibit unintentional non-adherence to medical recommendations due to decreased memory, poor executive function, decreased reaction time and decreased attentiveness.17,18

Work by Wukich and colleagues has elucidated the fact that patients with poorly controlled diabetes are at an increased risk for surgical site infections unless they are medically optimized.19 The authors are advocates for a hemoglobin A1c of less than 8% and smoking cessation perioperatively.19 Despite the known arteriovenous shunting and hyperemia that occurs with Charcot neuroarthropathy, it is important to recognize existing peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and if necessary, order noninvasive vascular studies. Also note that cardiac risk stratification is paramount in the Charcot patient as these patients carry an increased risk profile for adverse cardiac events perioperatively due to coronary artery stenosis.20-22

Work by Wukich and colleagues has elucidated the fact that patients with poorly controlled diabetes are at an increased risk for surgical site infections unless they are medically optimized.19 The authors are advocates for a hemoglobin A1c of less than 8% and smoking cessation perioperatively.19 Despite the known arteriovenous shunting and hyperemia that occurs with Charcot neuroarthropathy, it is important to recognize existing peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and if necessary, order noninvasive vascular studies. Also note that cardiac risk stratification is paramount in the Charcot patient as these patients carry an increased risk profile for adverse cardiac events perioperatively due to coronary artery stenosis.20-22

With respect to optimization of the surgical repair, patients presenting with Charcot deformity and diabetes mellitus have a marked increase in osteoclastic activity due to upregulation of receptor activation of nuclear factor kappa ligand (RANK-L) and a decrease in osteoblast response due to a decrease in osteoprotegerin. These patients also have decreased osteoid and collagen synthesis, which contributes to the poor bone quality that surgeons often encounter during Charcot reconstruction.

Many patients with diabetes and Charcot are known to have a loss of bone mineral density (BMD) and trabecular bone disorganization, which researchers have illustrated histologically and observed clinically.23 These factors support the adage of “double the fixation” and “double the follow-up” as the modulus of elasticity of the implants does not always match with that of bone. This creates a clinical scenario primed for hardware lucency and ultimate failure. The presence of fracture and fragmented Charcot indicates an overall decrease in bone mineral density in comparison to that of dislocation.24

In our practice, this finding has prognostic influence in the overall union rate and overall stability of the construct implemented. Additionally, consider comorbidities such as osteoporosis and renal osteodystrophy. In preparation for surgery, serology should include hemoglobin A1c; 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D; parathyroid hormone; serum calcium and C-telopeptide, which is a measure of type I collagen used to determine bone mineral density by evaluating the patient’s ability to resorb bone and be metabolically active. C-telopeptide can also measure the efficacy of pharmacologic influences on bone mineral density.

Pertinent Surgical Considerations

There are many different options when approaching Charcot deformity from a surgical perspective. One can manage Charcot deformity through a combination of several different techniques including exostectomy, Achilles tendon lengthening, osseous debridement, realignment osteotomy and selective arthrodesis by incorporating internal fixation, external fixation and/or orthobiologics. Prevention of ulceration and progression of bone deformity is the primary rationale for a patient to undergo Charcot reconstruction.

Early literature by Bevan and colleagues points to a negative prognostic influence of the lateral talo-first metatarsal angular relationship of greater than -27 degrees.25 Hastings and coworkers were further able to categorize radiographic progression over a two-year period, highlighting the importance of lateral column/cuboid collapse.26 Literature such as this provides surgeons treatment targets to facilitate maintenance of the correction through a deliberate surgical approach.

Developing a surgical plan includes identifying the Charcot stage and location (as more proximal Charcot leads to a worse prognostic outcome with respect to deformity and ulceration). Follow this with deformity planning, staging the procedure as indicated and subsequently determining the fixation strategy. The ultimate goal of Charcot reconstruction is a solid construct that puts the patient at decreased risk for further breakdown with a foot that is able to bear weight in a shoe or brace with stable hindfoot alignment. Important principles for reconstruction are to align the heel under the mechanical axis of the lower leg with passive dorsiflexion of 5 degrees past neutral and the metatarsal heads perpendicular to the heel with weight evenly distributed.27 It is important to stabilize the adjacent joints and incorporate the use of orthobiologics in areas where bone quality or deformity require additional support.

Effective Beaming And External Fixation: What You Should Know

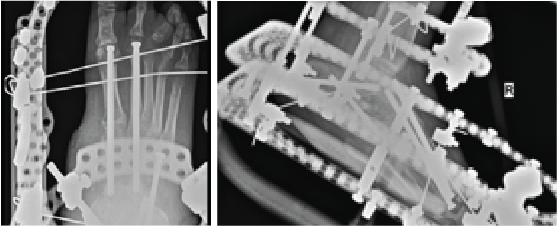

Popularized by Sammarco and colleagues, definitive Charcot reconstruction in a “superconstruct” fashion affirms the need for rigid fixation across the joints and ensuring adequate spanning of the “zone of injury” in order to achieve absolute stability.28 The principle of “beaming” or “intramedullary foot fixation” has continued to gain popularity since its introduction by Grant and coworkers.29 Other authors have since performed this technique with excellent results and osseous union ranging from 73 and 100 percent.28-31 Lamm and colleagues further elucidated technical principles and specific guidelines for accurate screw placement and deformity correction.32

The advantages of intramedullary fixation are numerous as it allows for appropriate spanning of the Charcot segment, incorporates minimally invasive techniques and preserves foot length and anatomic alignment, all through a rigid load sharing system.32 This becomes increasingly important as preservation of periarticular soft tissue supports the neurogenic support to the bone and periosteal blood supply.

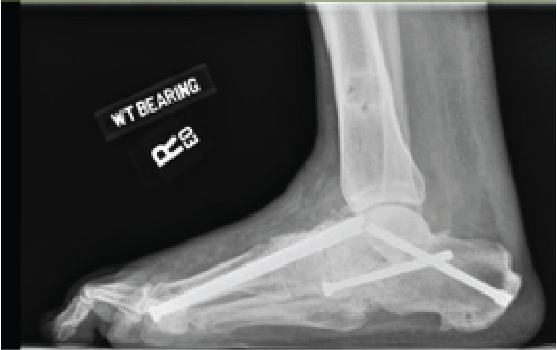

Hindfoot stability through fusion has proven successful in Charcot deformity correction with the incorporation of retrograde intramedullary nail fixation. Studies have indicated that intramedullary nail fixation interferes with endosteal blood flow initially but patients subsequently have complete restoration after three weeks in the absence of reaming and complete restoration in six weeks if reaming occurred.33 Typical indications for external fixation are when the patient is not amenable to casting, the deformity cannot have acute correction, evidence or suspicion for osteomyelitis, localized soft tissue infection, or when there is inadequate bone for internal fixation.34

In our experience, a useful indication for external fixation is in the setting of significant concomitant ankle and subtalar joint Charcot in which the calcaneal substrate becomes denuded and is not a stable foundation for intramedullary nail fixation. Many surgeons prefer a combination of intramedullary nail fixation with adjunctive external fixation. Researchers have proven that a combination of internal intramedullary nailing with supplemental external ring fixation has not decreased limb salvage rates.35 The literature seems to support that intramedullary nail fixation leads to higher rates of union but more revision surgery and complications whereas external fixation commonly incurs pin site complications.36,37

In Conclusion

Charcot neuroarthropathy in the diabetic population remains in the forefront as it poses the greatest of complications to our patients and remains a challenging dilemma for the foot and ankle specialist. By adhering to sound surgical principles and remaining fluid in their surgical approach by continuing to learn from peers in the field, surgeons can obtain excellent long-standing clinical results.

Dr. Mayer is a second-year resident with the Veterans Affairs Medicare Health Care System and the Rubin Institute for Advanced Orthopaedics at Sinai Hospital of Baltimore.

Dr. Wynes is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Orthopaedics at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. He is a Fellow of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons.

References

- Grear BJ, Rabinovich A, Brodsky JW. Charcot arthropathy of the foot and ankle associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Foot Ankle Int. 2013: 34(11):1541–7.

- Sohn MW, Stuck RM, Pinzur M, Lee TA, Budiman-Mak E. Lower-extremity amputation risk after Charcot arthropathy and diabetic foot ulcer. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33(1):98-100.

- Glover JL, Weingarten MS, Buchbinder DS, Poucher RL, Deitrick GA 3rd, Fylling CP. A 4-year outcome-based retrospective study of wound healing and limb salvage in patients with chronic wounds. Advances Wound Care. 1997; 10(1):33–38.

- Eichenholtz SN. Charcot Joints. Thomas, Springfield, Ill., 1996, pp. 1337-1348.

- Schon LC, Easley ME, Weinfield SB. Charcot neuroarthropathy of the foot and ankle. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1998; 349:116-131.

- Sanders LJ, Frykberg RG. The Charcot foot. In: Frykberg RG (ed.) The High Risk Foot in Diabetes Mellitus, First Edition. Churchill Livingstone, New York, 1991, pp. 325-335.

- Brodsky JW, Rouse AM. Exostectomy for symptomatic bony prominences in diabetic Charcot feet. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1993; 296:21-26.

- Schon LC, Easley ME, Cohen I, Lam PW, Badekas A, Anderson CD. The acquired midtarsus deformity classification- interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility. Foot Ankle Int. 2002; 23(1):30-36.

- Catanzariti AR, Mendicino R, Haverstock B. Ostectomy for diabetic neuroarthropathy involving the midfoot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2000; 39(5):291-300.

- Baumhauer JF, O’Keefe RJ, Schon LC, Pinzur MS. Cytokine-induced osteoclastic bone resorption in charcot arthropathy: an immunohistochemical study. Foot Ankle Int. 2006; 27(10):797–800.

- Armstrong DG, Todd WF, Lavery LA, et. al. The natural history of acute Charcot’s arthropathy in a diabetic foot specialty clinic. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1997; 87(6):272-278.

- Saltzman CL, Hagy ML, Zimmerman B, Estin M, Cooper R. How effective is intensive nonoperative initial treatment of patients with diabetes and Charcot arthropathy of the feet? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005; (435)185-90.

- Smith C, Kumar S, Cusby R. The effectiveness of non-surgical interventions in the treatment of Charcot foot. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2007; 5(4):437-449.

- Lowery NJ, Woods JB, Armstrong DG, Wukich DK. Surgical management of Charcot neuroarthropathy of the foot and ankle: A systematic review. Foot Ankle Int. 2012; 33(2):113–21.

- Pinzur MS. Current concepts review: Charcot arthropathy of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2007:28(8):952–9.

- Gil J, Schiff AP, Pinzur MS. Cost comparison: limb salvage versus amputation in diabetic patients with Charcot foot. Foot Ankle Int. 2013; 34(8):1097–9.

- Natovich R, Kushnir T, Harman-Boehm I, Margalit D, Siev-Ner I, Tsalichin D, Volkov I, Giveon S, Rubin-Asher D, Cukierman-Yaffe T. Cognitive dysfunction: part and parcel of the diabetic foot. Diabetes Care. 2016; 39(7):1202-1207.

- Mehta NN, McGillicuddy FC, Anderson PD, Hinkle CC, Shah R, Pruscino L, Tabita-Martinez J, Sellers KF, Rickels MR, Reilly MP.. Experimental endotoxemia induces adipose inflammation and insulin resistance in humans. Diabetes. 2010; 59(1):172-181.

- Wukich DK, Crim BE, Frykberg RG, Rosario BL. Neuropathy and poorly controlled diabetes increase the rate of surgical site infection after foot and ankle surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(10):832–839.

- Young BA, Lin E, Von Korff M, et al. Diabetes complications severity index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and healthcare utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2008; 14(1):15–23.

- Gazis A, Pound N, Macfarlane R, et al. Mortality in patients with diabetic neuropathic osteoarthropathy (Charcot foot). Diabet Med. 2004; 21(11):1243-1246.

- Pitocco D, Marano R, Di Stasio E, et al. Atherosclerotic coronary plaque in subjects with diabetic neuropathy: the prognostic cardiovascular role of Charcot neuroarthropathy—a case-control study. Acta Diabetologica. 2014; 51(4):587-593.

- La Fontaine J, Shibuya N, Sampson HW, Valderrama P. Trabecular quality and cellular characteristics of normal, diabetic and Charcot bone. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011; 50(6):648-653

- Herbst SA, Jones KB, Saltzman CL. Pattern of diabetic neuropathic arthropathy associated with the peripheral bone mineral density. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004; 86(3):378-383.

- Bevan WP, Tomlinson MP. Radiographic measures as a predictor of ulcer formation in diabetic charcot midfoot. Foot Ankle Int. 2008; 29(5):568-73.

- Hastings MK, Johnson JE, Strube MJ, et al. Progression of foot deformity in Charcot neuropathic osteoarthropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013; 95(13):1206-1213.

- Lamm BM, Stasko PA, Gesheff MG, Bhave A. Normal foot and ankle radiographic angles, measurements, and reference points. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016; 55(5):991-998.

- Sammarco VJ. Superconstructs in the treatment of Charcot foot deformity: plantar plating, locked plating, and axial screw fixation. Foot Ankle Clin. 2009; 14(3):393-407.

- Grant WP, Garcia-Lavin S, Sabo R. Beaming the columns for Charcot diabetic foot reconstruction: a retrospective analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011; 50(2):182-189.

- Wiewiorski M, Valderrabano V. Intramedullary fixation of the medial column of the foot with a solid bolt in Charcot midfoot arthropathy: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012; 51(3):379-381.

- Cullen BD, Weinraub GM, Van Gompel G. Early results with use of the midfoot fusion bolt in Charcot arthropathy. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2013; 52(2):235-238.

- Lamm BM, Siddiqui NA, Nair AK, LaPorta G. Intramedullary foot fixation for midfoot Charcot neuroarthropathy. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012; 51(4):531-536.

- Rhinelander FW, Stewart CL, Wilson JW, et al. Growth of tissue into a porous, low modulus coating on intramedullary nails: an experimental study. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1982; 164:293-305.

- Conway JD. Charcot salvage of the foot and ankle using external fixation. Foot Ankle Clin. 2008; 13(1):157-173.

- Devries JG, Berlet GC, Hyer CF. A retrospective comparative analysis of Charcot ankle stabilization using an intramedullary rod with or without application of circular external fixator—utilization of the retrograde arthrodesis intramedullary nail database. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012; 51(4):420-425.

- Dayton P, Feilmeier M, Thompson M, et al. Comparison of complications for internal and external fixation for Charcot reconstruction: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2015; 54(6):1072-1075.

- Lee DJ, Schaffer J, Chen T, Oh I. Internal versus external fixation of charcot midfoot deformity realignment. Orthopaedics. 2016; 39(4):595-601.

For further reading, see “Emerging Concepts In Beaming For Charcot” in the March 2017 issue of Podiatry Today, “Do Superconstructs Offer More Biomechanically Sound Fixation Principles For Charcot?” in the January 2016 issue or “When Should You Operate On The Charcot Foot?” in the March 2015 issue.

For more insights on Charcot neuroarthropathy, attend Dr. Wynes’ lecture, “A Practical Approach to the Management of Charcot Neuroarthropathy,” at the inaugural Advance by Podiatry Today meeting Oct. 13–15 in Chicago. To register, visit www.podiatrytoday.com/advance/register.