ADVERTISEMENT

Emerging Concepts In Plantar Plate Repair

Plantar plate insufficiency or rupture can lead to a variety of complications, including hammertoe or a dislocated toe. Drawing upon his clinical experience as well as the literature, this author reviews keys to the clinical exam, offers insights on diagnostic imaging and provides pearls on dorsal procedures as well as primary repair.

Plantar plate insufficiency or rupture can lead to a variety of complications, including hammertoe or a dislocated toe. Drawing upon his clinical experience as well as the literature, this author reviews keys to the clinical exam, offers insights on diagnostic imaging and provides pearls on dorsal procedures as well as primary repair.

There are a variety of terms for describing a common pathologic process of inflammation or injury to the plantar plate that results in the plate’s deterioration, either by attenuation or frank rupture. These terms include crossover toe, overlapping hammertoe, capsulitis, bursitis, pre-dislocation syndrome and metatarsalgia. The end result is an unstable and often painful hammertoe that can result in dislocation of the toe.

This article will detail my 20 years of clinical and surgical observations and experience in treating this condition. As medicine is an ever evolving science and art, there remains much more to learn about many conditions. Plantar plate repair is front and center as one of the more challenging conditions to manage in podiatry today.

The plantar plate is a fibrocartilaginous tissue that is the direct insertion of the plantar fascia into the base of the phalanges of the lesser toes. It is intracapsular and is the direct structure that the metatarsal head rests upon in stance and propulsion. It is typically 2 to 3 mm thick and the undersurface of the plantar plate houses the flexor tendons within the flexor retinaculum. At the level of the metatarsal head, the flexor brevis divides as it passes with the flexor longus tendon toward the phalanges. The flexor tendons rest slightly medial to the midline under the metatarsal heads, which accounts for why medially drifting toes are more common than laterally drifting toes.

Plantar plate insufficiency tends to be more common in women than men, presumably related to footwear that increases vertical peak pressures under the second toe.1 There tends to be an association with hallux valgus as well. Interestingly (and with no explanation), plantar plate ruptures appear to be primarily a disease of Caucasians. There is also a tendency for patients to have received one or more cortisone injections into the second metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) or second intermetatarsal space prior to joint subluxation or dislocation. Younger or male patients favor intense physical activity, including distance running.

Plantar plate insufficiency tends to be more common in women than men, presumably related to footwear that increases vertical peak pressures under the second toe.1 There tends to be an association with hallux valgus as well. Interestingly (and with no explanation), plantar plate ruptures appear to be primarily a disease of Caucasians. There is also a tendency for patients to have received one or more cortisone injections into the second metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) or second intermetatarsal space prior to joint subluxation or dislocation. Younger or male patients favor intense physical activity, including distance running.

Pertinent Insights On The Pathogenesis Of Plantar Plate Insufficiency

Plantar plate injuries are most common around the second toe but can occur in any of the lesser toes and also in multiple joints.2 I theorize that the second toe is most commonly involved due to two anatomic tenets: the second metatarsal is naturally the longest metatarsal and the second metatarsal locks into the mortise of the midfoot, thereby making the mortise the pivot point for forefoot frontal plane adaptation. Both of these conditions lead to the second MPJ being a late-phase propulsion contact point with considerable peak pressures that are unable to divert medially or laterally. Coupled with a hallux valgus deformity (which destabilizes the first MPJ and renders the first ray “hypermobile”) or increased activity (sports, high-heeled shoes), there is a tendency for inflammation of the plantar plate.

Increased pressure leads to inflammation, which typically leads to pain. “Pre-dislocation syndrome” refers to early-stage inflammation with pain and little deformity. Weakness can ensue with an increased duration of symptoms and mis-intentioned corticosteroid injection therapy can cause further weakening. It is common to have a misdiagnosis of second intermetatarsal space neuroma, especially in light of a medial splaying second toe. Dogmatic teachings suggested that a splay between the toes was indicative of an enlarged nerve between the metatarsal heads.3

Increased pressure leads to inflammation, which typically leads to pain. “Pre-dislocation syndrome” refers to early-stage inflammation with pain and little deformity. Weakness can ensue with an increased duration of symptoms and mis-intentioned corticosteroid injection therapy can cause further weakening. It is common to have a misdiagnosis of second intermetatarsal space neuroma, especially in light of a medial splaying second toe. Dogmatic teachings suggested that a splay between the toes was indicative of an enlarged nerve between the metatarsal heads.3

In reality, a plantar lateral rupture of the plantar plate leads to lateral weakness and since the flexor tendons lie medial to the midline, subluxation of the flexor tendons in a medial direction further propagates medial toe drift. Hallux valgus compounds the problem as crowding of the second toe encourages dorsal subluxation of the toe, which further increases plantar pressure on the plantar plate.

A Guide To The Clinical Exam

The most common early features of plantar plate injury are inflammation and pain. Pain is typically plantar to the toe and distal at the level of the sulcus. Typically, there is not pain directly under the metatarsal head. In many cases, plantar lateral pain may be a suspected symptom of a neuroma in the second intermetatarsal space. One of the most common but subtle features of early inflammation is dorsal edema. Clinicians may miss this if they are unable to distinguish the tenting of the extensor tendons under the skin in contrast to the uninvolved foot. Dorsal edema with plantar sulcus pain should increase the clinician’s suspicion for an intra-articular source of pathology, such as plantar plate inflammation (joint effusion leading to dorsal edema). Dorsal edema would conversely exclude a plantar neuroma diagnosis as a plantar neuroma would not likely cause dorsal edema.

Failure of the toe to touch the ground should also increase one’s suspicion of a plantar plate disruption. Normal windlass mechanism loading of the plantar fascia with weightbearing places natural tension on the plantar plate and is the primary stabilizer that maintains toe purchase in stance. In many cases, late-stage patients with a temporarily remote rupture may not have any plantar pain. Questioning their history will usually reveal a period of pain that was most intense when the condition began.

Failure of the toe to touch the ground should also increase one’s suspicion of a plantar plate disruption. Normal windlass mechanism loading of the plantar fascia with weightbearing places natural tension on the plantar plate and is the primary stabilizer that maintains toe purchase in stance. In many cases, late-stage patients with a temporarily remote rupture may not have any plantar pain. Questioning their history will usually reveal a period of pain that was most intense when the condition began.

A stress drawer examination will also reveal a complete rupture of the plantar plate. A positive “pucker” sign, in which the skin visibly rolls over the base of the phalanx when the phalanx is stressed dorsally in the sagittal plane, indicates disruption of the plantar plate. Be cautious with this examination technique as patients with sulcus pain on palpation may experience aggravation of pain. For some patients, one can dislocate and relocate the toe manually. When it comes to patients with longstanding rupture, manual relocation may not be possible.

For patients who have had prior surgery, one should assess for scar tissue contracture around the MPJ and within the digit. Patients may have pain secondary to nerve entrapment (stump neuroma), fat pad atrophy and flail toe. Patients may also have a floating toe as a result of a shortening metatarsal osteotomy. One needs to assess multiple factors as part of formulating a treatment plan. Openly discuss realistic expectations with the patient before embarking on more surgery. Revision surgery carries unique challenges so the experience of the surgeon is probably the most important factor in achieving a predictable and acceptable outcome for the patient.

Key Pointers On Effective Diagnostic Imaging

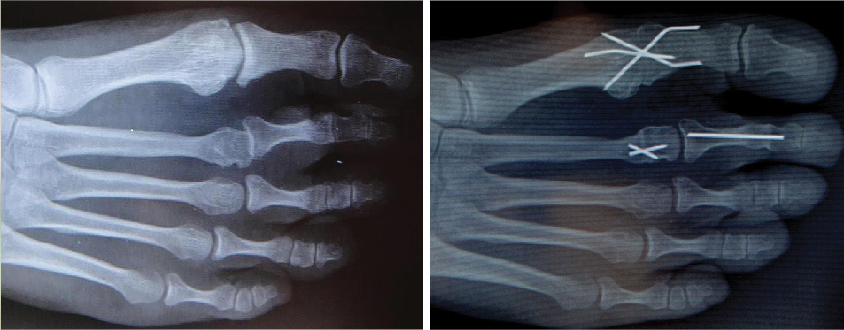

Plain film weightbearing radiographs are the first and often only adjunct exam needed to characterize the clinical diagnosis of plantar plate disruption. The lateral image will indicate a rectus, contracted, subluxed or dislocated joint. Assess arthritis within the joint as longstanding deformities can demonstrate bony erosion of the dorsal aspect of the metatarsal head and/or phalangeal base. One can best evaluate transverse plane deformity on the dorsal plantar image as well as any associated first ray or lesser ray deformities. Plain film radiography also provides the baseline for future comparison regarding progression of the deformity as well as assessing post-op healing.

Plain film weightbearing radiographs are the first and often only adjunct exam needed to characterize the clinical diagnosis of plantar plate disruption. The lateral image will indicate a rectus, contracted, subluxed or dislocated joint. Assess arthritis within the joint as longstanding deformities can demonstrate bony erosion of the dorsal aspect of the metatarsal head and/or phalangeal base. One can best evaluate transverse plane deformity on the dorsal plantar image as well as any associated first ray or lesser ray deformities. Plain film radiography also provides the baseline for future comparison regarding progression of the deformity as well as assessing post-op healing.

There are a host of other imaging studies that can be helpful in certain settings. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is probably the most useful tool coupled with plain film radiographs in assessing other conditions as well as diagnosing a plantar plate disruption. The MRI is helpful in identifying stress fractures, arthritis, inflammation, tendon pathology and tumors. A MRI is also useful but not universally diagnostic in confirming the clinical diagnosis of a plantar plate rupture.

In addition to plain film radiography and MRI, authors have reported the use of diagnostic ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) and arthrogram imaging.4 Each of these has value in assisting with increased information regarding the character of each patient’s condition although no individual test is 100 percent sensitive or specific in making the diagnosis of a plantar plate injury. In general, one makes the diagnosis based on a compilation of patient history, physical exam findings and weightbearing radiographs, which one can supplement with ancillary imaging studies when necessary. Do not reflexively order additional imaging studies on every patient.

Can Conservative Care Have An Impact?

Base the choice of treatments on symptoms and whether the patient’s stage is acute or chronic. Encourage activity and shoe modification with avoidance of high heels. One can utilize typical anti-inflammatory agents (topical or oral) or compression therapy to control edema, and ice to reduce swelling and pain. Off-weight padding can be helpful to reduce vertical pressure and callus debridement can provide symptomatic relief.

Perhaps the most effective mode of conservative treatment is sling padding or tape strapping the toe in a reduced position so it purchases the ground. For many patients, there is an immediate reduction or elimination of pain. This should also serve to support the diagnosis of a plantar plate injury and discourage the diagnosis of an intermetatarsal space neuroma since it is implausible that reducing the contracture of the MPJ would help if the symptoms were actually the result of a neuroma. Tape strapping the toe is also effective in preventing worsening of the condition and can prevent dislocation. This is especially effective for patients with early-stage pre-dislocation syndrome and if one does it consistently for an extended period of time (weeks to months), this can arrest progression and resolve symptoms.

Keys To Hammertoe Correction And Dorsal Procedures

Plantar plate injuries rarely require only operating on the plantar plate. This is one area where opinions vary most among foot and ankle surgeons. There are many acceptable ways of surgically achieving pain relief for this condition and they range from complex reconstruction to amputation. There are also many ways to achieve desired effects at multiple levels of deformity correction. I will simply outline my approach to treating this condition and attempt to justify each component of the repair. Please remember that this is just one way of addressing the complex crossover hammertoe and is not universally effective in all cases.

The mainstay of my assessment and treatment hinges on whether the plantar plate is disrupted and whether the toe is dislocated. In the majority of cases, the plate is insufficient to maintain toe purchase and there is not dislocation. I assume that most surgeons agree that toe purchase is an important measuring tool in assessing hammertoe deformities and their correction. Therefore, simulation of weightbearing on the operating room table is necessary.

Performing a Kelikian push-up test on a supine patient is unreliable in producing true ground reactive force as proximal tension on the skin can falsely plantarflex the toe. To this end, we use an instrument tray lid/flat plate pressed up against the entire bottom of the foot intraoperatively to continually assess the effect of each maneuver and sequentially perform the next maneuver until the toe has ground purchase.

In most cases, there is a hammertoe contracture and I perform a proximal interphalangeal joint arthrodesis with a buried K-wire (in slight flexion so as not to be too straight). If the toe is still unable to touch the ground, then we open the MPJ dorsally and perform an open Z-plasty of the extensor digitorum longus tendon (and usually section the extensor brevis tendon). If reduction is inadequate, we then perform a dorsal MPJ capsulotomy. If the toe is medially deviated, we also perform a medial capsulotomy and vice versa for a laterally deviated toe (much less common). If reduction is inadequate, then we address the plantar plate.

At this stage, determine whether a metatarsal osteotomy is necessary, either to shorten the aberrantly long metatarsal (remember, the second metatarsal is naturally the longest) or to correct for transverse plane metatarsal deviation. One must realize that shortening a metatarsal creates the same effect as a toe with brachymetatarsia: a floating toe. This is counter to the desired toe purchase so surgeons must use care and discretion. The literature has well documented the predictable and pervasive complications of shortening metatarsal osteotomies. Therefore, I discourage the wholesale use of a metatarsal osteotomy in every case.

More common, in my experience, is the need for transverse plane MPJ correction. Medial toe deviation can lead to lateral bowing of the second metatarsal, which appears radiographically as a negative second-third intermetatarsal angle where the second metatarsal head abuts the third metatarsal head. This is a bony adaptation that occurs over time and one needs to recognize this and address it surgically.

To that en d, we utilize a transverse, translocating, Hohmann-type osteotomy detailed by Behrens and Goforth.5,6 This procedure enables the surgeon to structurally move the metatarsal back under the toe, similar to how we correct a bunion (but in the opposite direction). This is a vertical metaphyseal osteotomy in which the metatarsal head shifts one-fourth to one-third the width of the bone. Slight angulation of the cut can achieve a moderate amount of shortening should one desire this. Surgeons can use crossing (1.1 mm diameter) threaded K-wires for fixation. Performing additional soft tissue balancing can release contractures (medial capsule/collateral ligaments) and tighten the weak structures (lateral capsule).

d, we utilize a transverse, translocating, Hohmann-type osteotomy detailed by Behrens and Goforth.5,6 This procedure enables the surgeon to structurally move the metatarsal back under the toe, similar to how we correct a bunion (but in the opposite direction). This is a vertical metaphyseal osteotomy in which the metatarsal head shifts one-fourth to one-third the width of the bone. Slight angulation of the cut can achieve a moderate amount of shortening should one desire this. Surgeons can use crossing (1.1 mm diameter) threaded K-wires for fixation. Performing additional soft tissue balancing can release contractures (medial capsule/collateral ligaments) and tighten the weak structures (lateral capsule).

Surgeons can also employ tendon transfers (extensor digitorum brevis) to achieve adequate soft tissue balance and restore collateral tension. Others support a flexor to extensor tendon transfer and surgeons have employed a variety of techniques in this regard.7 However, flexor digitorum longus tendon transfer is associated with a persistently painful stiff toe. The need for a purely shortening osteotomy (Weil osteotomy) is less common but there are circumstances in which this is necessary, especially in the chronically dislocated toe.8,9

After completing the dorsal procedures (hammertoe straightening, extensor tendon lengthening, joint capsulotomy, metatarsal osteotomy), determine if there is adequate toe purchase. In most instances, there is still a floating toe. We then proceed to repair the plantar plate through a plantar approach.

What You Should Know About Primary Plantar Plate Repair

We utilize a linear plantar incision directly under the MPJ, from the edge of the sulcus under the toe to the junction of the arch/weightbearing fat pad. It is helpful to mark the incision as well as the proposed location of each suture prior to making the incision. We use an interrupted vertical mattress suture for closure.

Pay special attention to cut sharply through the skin and entire subcutaneous fascia (plantar fat pad) without undermining or unduly separating the chambers of fat. We try to create two “walls of fat” attached to the skin, which we will cleanly reapproximate at the end of the procedure. When reaching the deep fascia, about 1.5 cm under the skin, perform slight undermining to expose the curvilinear surface of the flexor retinaculum, medially and laterally to the level of the beginning of each adjacent deep transverse metatarsal ligament. Then open the deep fascia flexor retinaculum longitudinally to expose the flexor tendons, which rest in a medially seated groove under the metatarsal head. Inspect the tendons and retract them medially in the arm of a self-retaining retractor. At this level, split the flexor brevis tendon to allow passage of the flexor longus tendon.

With retraction of the flexor tendons, one can inspect the plantar plate. Surgeons will either find attenuation of the plate with a continuous layer of scar tissue and no obvious hole, or one may encounter a rupture hole in the plate. Attenuation leads to gross laxity in the plate and a spongy thickening of the tissue, often to a thickness of 8-10 mm (a normal cartilaginous plate is 3 mm thick). A rupture hole is most commonly visible in the lateral portion of the plate, which corresponds to a medial deviated toe. In most instances, the rupture is distal in the plate, close to the insertion on the base of the proximal phalanx. In rare instances, there is complete avulsion of the plate from the base of the phalanx and there can be a combination of a rupture hole with adjacent attenuation.

After inspection, repair the plantar plate with sutures. In the case of attenuation, one will have to remove a section of the diseased tissue and create a defect by which to close and tighten the laxity in the plate. When cutting out the section of tissue from the midsubstance of the plate, be careful not to cut too close to the phalangeal base in order to leave enough tissue to secure with sutures. Remove a medial to lateral fusiform wedge, exposing the metatarsal head. In the case of a medially deviated toe, one can remove a laterally based wedge so closure of the defect will effect more tightening of the lateral plate and thus impart transverse plane correction in addition to sagittal tightening of the joint.

After inspection, repair the plantar plate with sutures. In the case of attenuation, one will have to remove a section of the diseased tissue and create a defect by which to close and tighten the laxity in the plate. When cutting out the section of tissue from the midsubstance of the plate, be careful not to cut too close to the phalangeal base in order to leave enough tissue to secure with sutures. Remove a medial to lateral fusiform wedge, exposing the metatarsal head. In the case of a medially deviated toe, one can remove a laterally based wedge so closure of the defect will effect more tightening of the lateral plate and thus impart transverse plane correction in addition to sagittal tightening of the joint.

For instances in which there is an obvious hole, use the defect to plicate the torn tissue. Debridement through the hole to “freshen up” the margins allows suture closure. Likewise, one can remove additional tissue on the proximal side of the defect to facilitate a tighter closure, allowing enough distal tissue to hold a suture. There will be a central ridge of tissue that remains on the bottom of the plate that was the edge of the flexor retinaculum and one can cleanly excise this as it will not need repair.

We utilize a non-absorbable monofilament 3/0 suture (nylon or polypropylene) to repair the plantar plate, using two adjacent over-over stitches to plicate the tissue defect. For a desirable degree of repair, one should overcorrect the position of the toe slightly, assuming there will be some late-stage dorsal drift to the toe. We avoid using braided sutures since they do not “slide” tight when securing the knot and we also use a non-absorbable suture to ensure that it will remain intact without dissolving. We run both sutures open and when they are in place, we tighten and knot them under tension while the assistant holds the toe downward.

There is no need to attempt to suture repair the flexor retinaculum but it is sometimes helpful to centralize a dislocated flexor digitorum longus tendon beneath the plantar plate. To this end, one can use an absorbable suture to tack the tendon centrally beneath the plantar plate. In instances of a chronically dislocated MPJ, the surgeon can use the flexor digitorum longus tendon to augment the reduction and repair of the plantar plate by applying distal tension to the tendon and suturing it into the base of the proximal phalanx.

In rare cases, there may be avulsion of the plantar plate from the phalangeal base with no viable tissue to suture into distally. In these cases, we place a suture anchor into the base of the proximal phalanx and pass the sutures proximally into the remaining plantar plate.

Following repair of the plantar plate, perform final closure using vertical mattress 5/0 nylon or polypropylene sutures to repair the subcutaneous fascia and skin in one step. We avoid placing any absorbable sutures in the deep tissues to reduce foreign body reaction and thereby reducing scarring. Then dress the wounds with multilayered compressive gauze and wraps.

Addressing Postoperative Management And Potential Complications

Patients can partially bear weight on the heel of the surgical foot and receive a surgical shoe and crutches/walker/Roll-A-Bout for assistance. Follow up with them at one week for a dressing change and then again at the second week following surgery. At two weeks, remove the plantar sutures and reinforce the wound with tape strips. Discourage the patient from fully bearing weight on the plantar scar until six weeks following surgery. One should also direct the recovery course around other bone procedures. At the six-week visit, the plantar skin will slough the thick epidermal eschar and this will reveal a remarkably supple fine line scar, which will continue to mature for up to a year following surgery.

No procedure is without potential complications. Plantar plate repair is similar in that respect. Under- and overcorrection are possible as is re-dislocation of the chronically dislocated toe. Plantar incision dehiscence or infection is extremely rare but possible. Vascular compromise and loss of a digit is possible but this has not occurred in more than 200 consecutive cases. Persistence of a plantar callus is common but a painful plantar scar is rare. In general, the plantar scar is typically difficult to locate by the one-year mark following surgery and is always more supple than the dorsal scars.

No procedure is without potential complications. Plantar plate repair is similar in that respect. Under- and overcorrection are possible as is re-dislocation of the chronically dislocated toe. Plantar incision dehiscence or infection is extremely rare but possible. Vascular compromise and loss of a digit is possible but this has not occurred in more than 200 consecutive cases. Persistence of a plantar callus is common but a painful plantar scar is rare. In general, the plantar scar is typically difficult to locate by the one-year mark following surgery and is always more supple than the dorsal scars.

A Few Thoughts About Emerging Devices And Techniques For Indirect Repair

There are several emerging technologies and systems that are intended to repair the plantar plate remotely through a dorsal approach. Some require the performance of a shortening metatarsal osteotomy to access the plantar plate. Others utilize suture passing needles and knotting systems that also can repair the collateral ligaments.

Once industry embraces a potentially new device market, an explosion of interest and devices follow. Accordingly, one will see emerging approaches and products for repair of the plantar plate as well. There are a few points of interest that warrant comment here. Most plantar plate injuries do not require a shortening metatarsal osteotomy. Most plantar plate insufficiency presents as attenuation of tissue (not a rupture hole), which requires plication by removal of redundant tissue, which is not possible with any of the current systems. Avoidance of a plantar incision for fear of a bad scar has no support of any scientific evidence or reports.

There is also the financial burden of these devices, which routinely exceed $1,000 per system. In short, repairing the plantar plate from the top of the foot is akin to plugging a leak in the basement floor by going through the roof of the house. Maybe you can do it but why would you do so?

Dr. Camasta is a Fellow of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons, and a Fellow of the American Society of Podiatric Surgeons. He is also a faculty member of the Podiatry Institute and a Fellow of the College of Physicians and Surgeons (Australia). Dr. Camasta is in private practice at Village Podiatry Centers in Atlanta.

References

- Camasta CA. Plantar plate repair of the second metatarsophalangeal joint. In McGlamry’s Comprehensive Textbook of Foot and Ankle Surgery, Fourth Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012, pp. 187-201.

- Fleming J, Camasta CA. Plantar plate dysfunction. In Reconstructive Surgery of the Foot and Leg, Update 2002. The Podiatry Institute, Inc. Tucker, GA, 2002.

- Ford LA, Collins KB, Christensen JC. Stabilization of the subluxed second metatarsophalangeal joint: flexor tendon transfer versus primary repair of the plantar plate. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1998; 37(3):217-22.

- Yu GV, Judge MS, Hudson JR, Seidelmann FE. Predislocation syndrome – progressive subluxation/dislocation of the lesser metatarsophalangeal joint. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002; 92(4):182-99.

- Berens TA. Laterally closing metatarsal head osteotomy in the correction of a medially overlapping digit. Clin Pod Med Surg. 1996; 13(2):293-307.

- Goforth WP, Urteaga AJ. Displacement osteotomy for the treatment of digital transverse plane deformities. Clin Pod Med Surg. 1996; 13(2):279-92.

- Myerson MS, Jung HG. The role of toe flexor-to-extensor transfer in correcting metatarsophalangeal joint instability of the second toe. Foot Ankle Int. 2005; 26(9):675-9.

- Migues A, Slullitel G, Bilbao F, Carrasco M, Solari G. Floating-toe deformity as a complication of the Weil osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int. 2004; 25(9):609-13.

- Trnka HJ, Muhlbauer M, Zetti R, Myerson MS, Ritschl P. Comparison of the results of the Weil and Helal osteotomies for the treatment of metatarsalagia secondary to dislocation of the lesser metatarsophalangeal joints. Foot Ankle Int. 1999; 20(2):72-79.

For further reading, see “Correcting The Crossover Toe With Direct Plantar Plate Repair” in the January 2014 issue of Podiatry Today, “A Guide To Conservative Care For Plantar Heel Pain” in the November 2013 issue or the DPM Blog “Obtaining A Rewarding Surgical Outcome With Plantar Plate Repair” by Doug Richie Jr., DPM, FACFAS.

For an enhanced experience, check out Podiatry Today on your iPad or Android tablet.