Current Perspectives On Nutrition And Wound Healing

Given that malnutrition and a loss of lean body mass can have an adverse effect on wound healing, clinicians should have a strong understanding of the impact of adequate protein intake and the pros and cons of different vitamin supplements. Accordingly, these authors offer a salient review of current guidelines and recommendations for facilitating optimal nutrition in patients with lower extremity wounds.

We often say “You are what you eat” and nutrition is a vital component to healing chronic wounds. It is imperative that regular nutrition counseling be a part of your initial and ongoing assessment for patients with wounds.

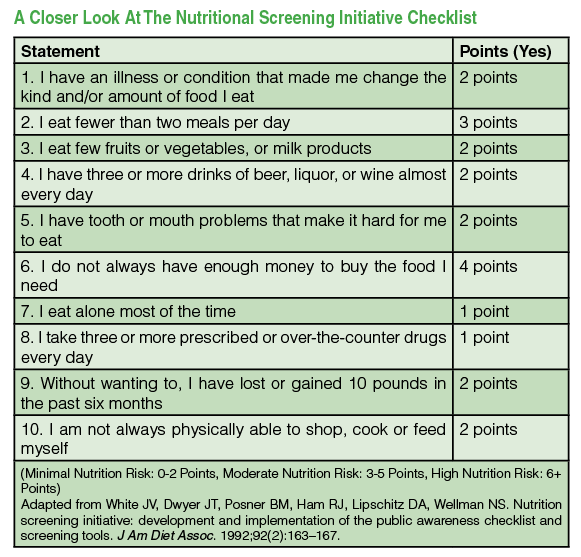

According to a study produced by Wissing and colleagues, patients who live by themselves (common in our elderly patients) are often malnourished as they may eat fewer meals or foods of lesser nutritional value.1 Clinicians may evaluate the nutrition of patients and their level of isolation through a series of standardized questionnaires (see “A Closer Look At The Nutritional Screening Initiative Checklist” at left and “A Guide To The Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire” below at right), or by interviewing patients as a part of the initial history taking. Clinicians play an influential role in nutrition intervention when a patient is susceptible to malnutrition, a condition that encompasses poor food selection or inappropriate caloric intake.1

According to a study produced by Wissing and colleagues, patients who live by themselves (common in our elderly patients) are often malnourished as they may eat fewer meals or foods of lesser nutritional value.1 Clinicians may evaluate the nutrition of patients and their level of isolation through a series of standardized questionnaires (see “A Closer Look At The Nutritional Screening Initiative Checklist” at left and “A Guide To The Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire” below at right), or by interviewing patients as a part of the initial history taking. Clinicians play an influential role in nutrition intervention when a patient is susceptible to malnutrition, a condition that encompasses poor food selection or inappropriate caloric intake.1

Patients who lose lean body mass or protein mass due to injuries or infections can experience worsening wound conditions and a delay in healing.1 Consequently, evaluating and maintaining proper nutrition in patients with chronic wounds are imperative.

Patients who lose lean body mass or protein mass due to injuries or infections can experience worsening wound conditions and a delay in healing.1 Consequently, evaluating and maintaining proper nutrition in patients with chronic wounds are imperative.

Lean body mass accounts for approximately 75 percent of a healthy human’s body weight.2 At age 40, we begin to lose up to 8 percent of muscle loss every decade thereafter.3 Sarcopenia, or weight loss with age, further accelerates due to inactivity, illness and poor nutrition.4 A loss of lean body mass can increase the risk of developing open wounds or halt the progress of wound healing. Lean body mass loss may accelerate even further in wound care patients as their bodies demand proteins stored in muscle and vital organs to contribute to their wound healing and inflammatory response.2 The greater the loss of lean body mass, the greater the risk of complications, including poor wound healing, increased incidence of infection and death. One can address sarcopenia and subsequent loss of lean body mass in affected patients with the adequate consumption of calories, protein and applicable supplements as we will discuss later in the article.

What You Should Know About Macronutrients

Macronutrients in wound healing include carbohydrates, fat and protein. Carbohydrates contribute to the production and secretion of insulin, but patients should consume them, especially simple sugar, in moderation so as not to induce hyperglycemia. Hyperglycemia inhibits granulocyte function and can increase inflammation and the incidence of infection. Fat stores can be a source of energy during the wound healing process and can spare some necessary proteins in doing so. Fat contributes to vitamin absorption and helps create an added layer of padding beneath the distressed skin.

Macronutrients in wound healing include carbohydrates, fat and protein. Carbohydrates contribute to the production and secretion of insulin, but patients should consume them, especially simple sugar, in moderation so as not to induce hyperglycemia. Hyperglycemia inhibits granulocyte function and can increase inflammation and the incidence of infection. Fat stores can be a source of energy during the wound healing process and can spare some necessary proteins in doing so. Fat contributes to vitamin absorption and helps create an added layer of padding beneath the distressed skin.

However, the most vital nutritional component to wound healing is protein. Protein is a major contributor to wound contraction, oncotic pressure, fibroblast and collagen synthesis, tissue remodeling, and angiogenesis.5

Optimal wound healing and lean body mass maintenance can occur when patients consume approximately 80 to 100 grams of protein every day.6 Protein consumption can come from various sources such as meat, poultry, fish, eggs, milk, tempeh and tofu.6 Patients can achieve daily protein levels through meals, snacks or supplements. Typically, 20 to 30 grams of protein provides a reasonable and attainable goal per sitting. Meals should be approximately three or more hours apart to maximize protein digestion and absorption.7

If patients prefer protein supplements, ready-made shakes from Ensure (Abbott Laboratories), Boost (Nestle Health Science) or, for patients with diabetes, Glucerna (Abbott Laboratories) are convenient and readily available in most grocery stores and pharmacies. Clinicians may want to consider writing a prescription for these supplements if they encounter malnourished patients and if patients are covered by insurance plans including Medicaid.

Patients should combine calorie and protein consumption with adequate fluid intake as well. Ideally, patients should aim to drink approximately 1 mL of water per kcal consumed every day or about 2 liters of water per day. Lack of fluids and subsequent dehydration can prevent delivering oxygen to the tissue in need. This is an important point as wound care patients need to remain hydrated to ensure an important element of arterial perfusion, skin turgor and oxygenation.8 In practice, we recommend plain water, unsweetened tea or flavored sparking water over soda, which may include unwanted sugar for our patients with diabetes. Patients who are suffering from dehydration, vomiting or diarrhea may add low-calorie rehydration tablets and powders, such as Nuun tablets (Nuun) and Skratch powder (Skratch Labs), to plain water to create an ideal fluid and electrolyte replacement solution.

Guidelines For Patients Achieving Optimal Body Weight

Obesity is a major social issue in the United States. Estimates are that two-thirds of the nation’s population is overweight or have a body mass index (BMI) greater than 25.8 Obesity closely correlates with various cardiovascular diseases and large truncal obesity causes swelling of the lower extremities, thereby complicating normal wound healing. We do recommend nutritional counseling and bariatric clinic consultations to our obese patients as long as they are receptive to the idea of attempting weight loss.

However, since many overweight patients and perhaps less mobile patients may not be able to exercise for increased calorie expenditure, they must limit their calorie intake drastically. This should happen under the direct supervision of registered dietitians and physicians, or perhaps with the help of bariatric surgery. In general, we do recommend cutting back on simple carbohydrate intake, which influences insulin resistance and blood glucose levels. Furthermore, we recommend that patients limit their intake of processed foods and meats, both of which are often high in calorie density and may increase the incidence of certain cancers as recently outlined by the World Health Organization.9

However, since many overweight patients and perhaps less mobile patients may not be able to exercise for increased calorie expenditure, they must limit their calorie intake drastically. This should happen under the direct supervision of registered dietitians and physicians, or perhaps with the help of bariatric surgery. In general, we do recommend cutting back on simple carbohydrate intake, which influences insulin resistance and blood glucose levels. Furthermore, we recommend that patients limit their intake of processed foods and meats, both of which are often high in calorie density and may increase the incidence of certain cancers as recently outlined by the World Health Organization.9

In our experience, we find that keeping a food diary and learning to control portions can lead to successful long-term weight loss. As a pound of fat is equivalent to 3,500 calories, in theory, you can achieve a pound of fat loss per week if you have a deficit of 500 calories per day. Patients may keep food diaries with mobile phone applications, such as My Fitness Pal, and can obtain portion control guidelines with Weight Watchers. Lastly, intermittent fasting, which involves skipping a meal by design, can promote fat loss by achieving nutritional ketosis and a drop in the serum insulin level.10

In contrast to overweight wound care patients, we do occasionally see frail patients with thin skin, pressure ulcers and poor wound healing as a result of malnourishment and being underweight. It is not uncommon to see patients with poor appetites because of chemotherapy treatments or chronic illnesses. In general, these patients should increase calorie and protein intake with the help of special supplements that have extra calories during or between meals.

In contrast to overweight wound care patients, we do occasionally see frail patients with thin skin, pressure ulcers and poor wound healing as a result of malnourishment and being underweight. It is not uncommon to see patients with poor appetites because of chemotherapy treatments or chronic illnesses. In general, these patients should increase calorie and protein intake with the help of special supplements that have extra calories during or between meals.

Ready-made supplements that combine both protein and additional calories include Ensure Plus (Abbott Laboratories) and Ensure Enlive (Abbott Laboratories). Pharmacological agents for anorexia and cachexia, such as megestrol (Megace, Bristol-Myers Squibb), may stimulate the appetites of selected patients. Feeding tubes are another interventional method for patients with problems swallowing or those at risk of aspiration pneumonia.

What The Evidence Says About Recommended Supplements

In addition to achieving adequate protein intake, it is recommended that wound care patients take beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) supplements. This is a minor metabolite of an essential amino acid called leucine. An HMB supplement contributes to protein homeostasis by downregulating degradation and increasing synthesis. Furthermore, HMB is a precursor for cholesterol formation in the cellular membranes of skeletal muscle. Accordingly, HMB supplements are clinically recommended as a means of increasing muscular strength and lean body mass.11 Twenty human clinical studies assert that 3 grams of HMB per day significantly decreased muscle damage and soreness, and increased lean body mass.11 Consequently, the recommended dosage for oral HMB is 3 grams per day.

Patients can achieve optimal muscle gains with the consumption of protein and HMB during or after exercise. Typically, elderly people should consume protein and HMB immediately following exercise to maximize the supplement’s potential benefits.

When appropriate, patients can combine protein and HMB supplements with oral administration of two essential amino acids, glutamine and arginine. Clinical studies in elderly wound care patients revealed that those who took HMB supplements that included arginine and glutamine exhibited increased collagen repair in contrast to those who took HMB alone.12 Glutamine serves as the primary source of energy for cells that are rapidly dividing, such as those of the new skin around a healing wound. The HMB supplement is commercially available with premade Ensure Enlive shakes or the Juven powdered drink mix (Abbott Laboratories).

When appropriate, patients can combine protein and HMB supplements with oral administration of two essential amino acids, glutamine and arginine. Clinical studies in elderly wound care patients revealed that those who took HMB supplements that included arginine and glutamine exhibited increased collagen repair in contrast to those who took HMB alone.12 Glutamine serves as the primary source of energy for cells that are rapidly dividing, such as those of the new skin around a healing wound. The HMB supplement is commercially available with premade Ensure Enlive shakes or the Juven powdered drink mix (Abbott Laboratories).

A Closer Look At Supplements We Do Not Recommend

Apart from protein, HMB, glutamine and arginine, vitamin supplements are often proposed to affect the progress of wound healing. Vitamin A plays a role in collagen synthesis and cross-linking processes, and patients can use vitamin A supplements at 10,000 IU daily over the course of 10-day interval.5 Contraindications for vitamin A supplementation, however, include protein deficiency and liver or renal failure.5 Like vitamin A, vitamin C contributes to cross-linking processes as well as wound tensile strength. One can prescribe vitamin C supplements at 250 mg per day. Finally, zinc supplements contribute to epithelialization, immunity and wound strength, and one can prescribe these for deficient patients at 220 mg per day.5

Despite the perceived roles vitamin A, vitamin C and zinc play in wound healing, we do not actively recommend these supplements to our own patients in our wound care center as the medical evidence in a clinical setting is not particularly strong. One trial, involving 20 humans who consumed 500 mg of vitamin C twice daily, found that test participants healed twice as quickly over the course of four weeks in comparison to the control participants.13

In regard to zinc supplements, patients with chronic venous ulcers who received 200 mg of zinc three times daily showed no difference in wound healing in comparison to the placebo patients after 12 weeks.14 Given the lack of strong evidentiary support for vitamin C and zinc supplements, we do not recommend multivitamin supplementation for our wound care patients with the sole exception of vitamin B complex for vegetarians who might be lacking these sources in their basic diets.

In Conclusion

The combination of appropriate amounts of daily calories and protein maintains the lean body mass, which is crucial for skin integrity, wound healing, organ and immune function, physical strength and prevention of premature death in frail, elderly individuals. Patients can maintain lean body mass with primary and secondary protein source intake, and readily available HMB supplements. The combination of HMB with protein contributes to protein metabolism and rebuilding lean body mass by regulating the human body’s protein homeostasis.7 Consequently and based on the clinical evidence presented, it is imperative that patients ensure they consume the adequate calories, recommended 80 to 100 grams of protein and 3 grams of HMB daily to help achieve optimal wound healing.

Dr. Suzuki is the Medical Director of the Tower Wound Care Centers at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Towers. He is also on the medical staff of the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and is a Visiting Professor at the Tokyo Medical and Dental University in Tokyo. He can be reached at Kazu.Suzuki@cshs.org.

Ms. Birnbaum is affiliated with Tower Wound Care Centers in Los Angeles.

References

- Wissing U, Lennernas M, Unosson M. Meal patterns and meal quality in patients with leg ulcers. J Hum Nutr Dietet. 2000; 13(1):3-12.

- Demling RH. Nutrition, anabolism, and the wound healing process: an overview. Eplasty. 2009;9:65-94.

- Baier S, Johannsen D, Abumrad N, et al. Year-long changes in protein metabolism in elderly men and women supplemented with a nutrition cocktail of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB), L-arginine, and L-lysine. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33(1):71-82.

- Kalyani RR, Corriere M, Ferrucci L. Age-related and disease-related muscle loss: the effect of diabetes, obesity, and other diseases. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014; 2(10):819–829.

- Kim J, Stefankiewicz S. Wound Healing: Clinical Nutrition Support Service. Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Available at https://www.med.upenn.edu/gec/user_documents/KimStefankiewiczWoundHealing.pdf .

- Suzuki K. Counseling wound care patients on nutrition and supplements. Podiatry Today. 2016; 29(3):28–29.

- Eitel J. How to consume 100g of protein per day. Livestrong. Available at https://www.livestrong.com/article/503318-how-to-consume-100g-of-protein-per-day/ . Published June 3, 2015.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Overweight and obesity statistics. Available at https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/Pages/overweight-obesity-statistics.aspx .

- World Health Organization. Q&A on the carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat. Available at https://www.who.int/features/qa/cancer-red-meat/en/ . Published October 2015.

- Collier R. Intermittent fasting: the science of going without. Can Med Assoc J. 2013; 185(9):E363–4.

- Wilson GJ, Wilson JM, Manninen AH. Effects of beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) on exercise performance and body composition across varying levels of age, sex, and training experience: A review. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008;5(1):1.

- Williams JZ, Abumrad N, Barbul A. Effect of a specialized amino acid mixture on human collagen deposition. Ann Surg. 2002;236(3):369-74; discussion 374-5.

- Ordman AR. Vitamin C twice a day enhances health. Health. 2010; 2(8):819–23.

- Hallbook T, Lanner E. Serum-zinc and healing of venous leg ulcers. Lancet. 1972; 2(7781):780–2