A Closer Look At A Minimally Invasive Approach To Lateral Ankle Repair

A minimally invasive arthroscopic approach may significantly improve functional outcomes for patients with lateral ankle instability. In addition to offering insights from the emerging literature, these authors share step-by-step surgical pearls for the all-inside arthroscopic Broström repair.

Ankle sprains are extremely common and one of the most frequent causes of emergency room visits.1,2 Researchers estimate that upward of 30,000 ankle sprains occur in the United States each day. That equals roughly 2 million per year. This leads to a heavy strain on the medical system, time off from work and decrease in quality of life.

Ankle sprains are extremely common and one of the most frequent causes of emergency room visits.1,2 Researchers estimate that upward of 30,000 ankle sprains occur in the United States each day. That equals roughly 2 million per year. This leads to a heavy strain on the medical system, time off from work and decrease in quality of life.

Eighty-five percent of ankle sprains involve the lateral ankle ligaments.3,4 The anterior talofibular ligament is the most commonly injured lateral ankle ligament and most recover fully without limitation. There is a high re-injury rate with ankle sprains, reportedly as high as 34 percent.3 Chronic ankle instability can develop and reportedly occurs in 10 to 20 percent of ankle sprains.3

The current gold standard for treatment of ankle sprains includes conservative care in the form of rest, ice, elevation of the affected extremity and compression with bracing and functional rehabilitation. If conservative treatment fails, surgical stabilization of ankle ligaments is warranted. Historically, physicians have treated lateral ankle stabilization with an open approach using either anatomic repair or non-anatomic repair. There have been excellent results in long-term studies. Bell and coworkers reported the long-term follow-up data using the Broström technique for 23 ankles with lateral instability.5 The mean follow-up was 26.3 years and the mean functional score was 92 of 100.

The current gold standard for treatment of ankle sprains includes conservative care in the form of rest, ice, elevation of the affected extremity and compression with bracing and functional rehabilitation. If conservative treatment fails, surgical stabilization of ankle ligaments is warranted. Historically, physicians have treated lateral ankle stabilization with an open approach using either anatomic repair or non-anatomic repair. There have been excellent results in long-term studies. Bell and coworkers reported the long-term follow-up data using the Broström technique for 23 ankles with lateral instability.5 The mean follow-up was 26.3 years and the mean functional score was 92 of 100.

There are numerous reports that show intra-articular pathology exists in patients with chronic ankle instability. Cottom and colleagues show that 100 percent of 28 patients reviewed had some form of intra-articular synovitis along with numerous other intra-articular lesions they observed in the cohort.6 Hintermann and colleagues reported on 148 patients with intra-articular pathologic features associated with lateral ankle instability, and found that 66 percent of patients had cartilage damage.7 Ferkel and coworkers reported on 21 ankles that had ankle arthroscopic evaluation before a Broström–Gould procedure.8 They identified pathologic intra-articular findings in 95 percent of their patients.

A Pertinent  Guide To The Authors’ Surgical Technique

Guide To The Authors’ Surgical Technique

In our practice, we routinely treat lateral ankle instability with minimally invasive techniques and our most common approach in this regard is the all-inside arthroscopic Broström repair with proximal anchor augmentation as described by Cottom and Richardson in 2017.9

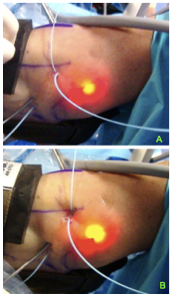

After ensuring supine positioning of the patient and the administration of a popliteal nerve block and general anesthesia, we place a well-padded thigh tourniquet on the patient, and position a thigh holder to elevate the foot a few inches off the operating table. Then we outline the distal fibula, peroneal tendons and intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerves with a surgical marker. We then apply a noninvasive ankle distractor and use manual traction to distract the ankle.

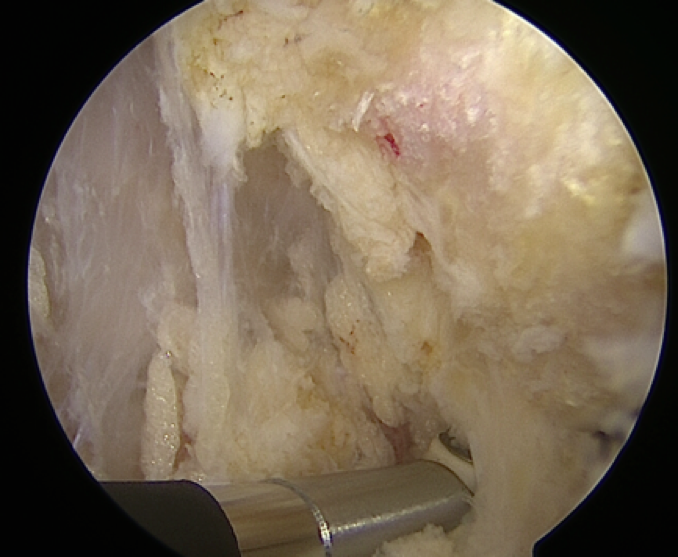

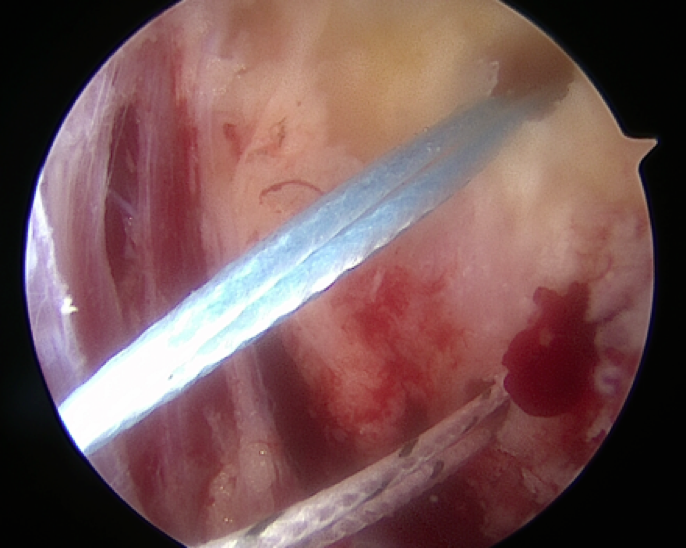

Establish standard anteromedial and anterolateral portals, and perform extensive arthroscopic debridement using a 4 mm camera and shaver. We are then able to address any intra-articular pathology at the time of arthroscopy before proceeding to the lateral ankle stabilization. Then direct attention toward the anterolateral gutter, carrying out extensive debridement in order to remove any synovitis or bone spurs, which may result in impingement. Debridement of the distal fibula to bone entails using ablation to facilitate debridement of capsular and ligamentous adhesions. Then obtain lateral stabilization of the ankle joint with one of two constructs.

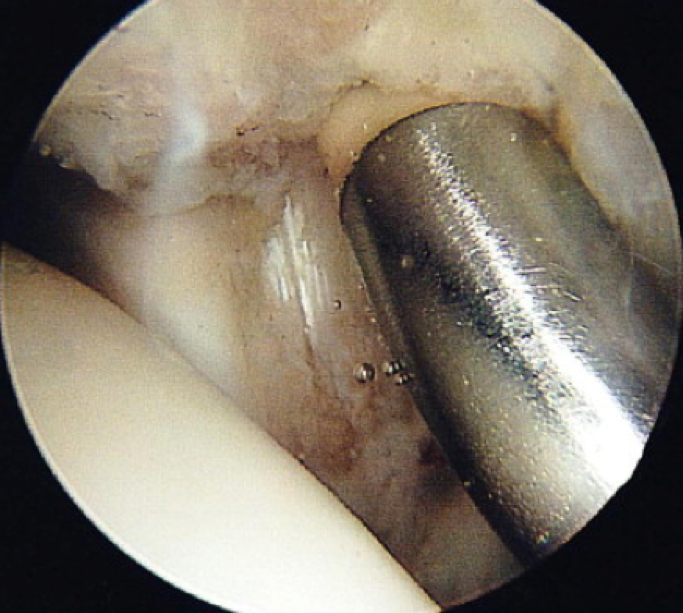

Next we p lace a drill guide for the first anchor through the anterolateral portal directly midline in the coronal plane and approximately 1 cm superior to the distal aspect of the fibula. We drill a guide hole, then insert the anchor and seat it in place with a mallet. One can confirm the placement of the anchor with the arthroscope. The anchor system we use is a 3.0 mm bioabsorbable anchor (BioComposite SutureTak®, Arthrex).

lace a drill guide for the first anchor through the anterolateral portal directly midline in the coronal plane and approximately 1 cm superior to the distal aspect of the fibula. We drill a guide hole, then insert the anchor and seat it in place with a mallet. One can confirm the placement of the anchor with the arthroscope. The anchor system we use is a 3.0 mm bioabsorbable anchor (BioComposite SutureTak®, Arthrex).

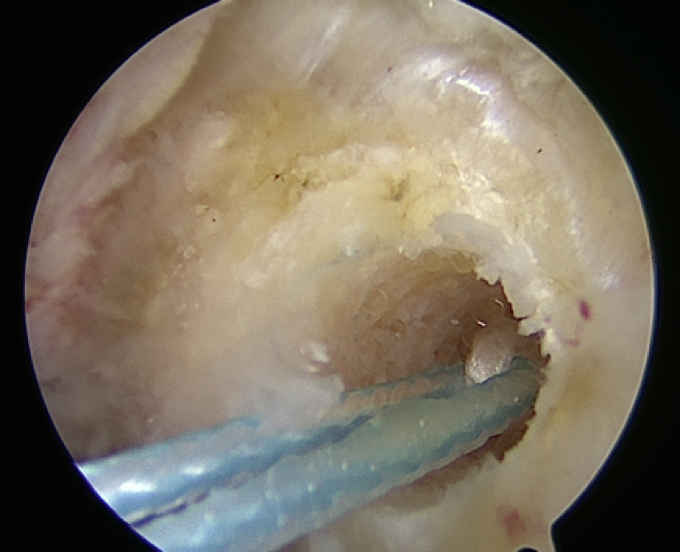

Then remove the drill guide and the sutures should now be visible exiting the anterolateral portal. We then use a Micro SutureLasso (Arthrex) to capture the anterior talofibular ligament, ankle capsule and inferior extensor retinaculum. We place the Micro SutureLasso percutaneously in the sinus tarsi region and angle it toward the anterolateral portal, placing the first pass approximately 1.5 cm to 2 cm inferior and anterior to the distal fibula.

Then remove the drill guide and the sutures should now be visible exiting the anterolateral portal. We then use a Micro SutureLasso (Arthrex) to capture the anterior talofibular ligament, ankle capsule and inferior extensor retinaculum. We place the Micro SutureLasso percutaneously in the sinus tarsi region and angle it toward the anterolateral portal, placing the first pass approximately 1.5 cm to 2 cm inferior and anterior to the distal fibula.

Then advance the nitinol wire and use it to capture one strand from the suture anchor, pulling the wire back through the skin, exiting in the sinus tarsi region. Then perform the same procedure to capture the other strand of the suture from the anchor. This occurs approximately 1 cm anterior and superior to site one of the first strand, advancing the lasso percutaneous in the same aforementioned manner and exiting the anterolateral portal. We then pull back strand two from the suture anchor through the skin exiting site two.

Using the same technique, we insert a second bone anchor in the fibula at the level of the lateral talar dome. The strands exit the anterolateral portal and one would again use a Micro SutureLasso to capture the individual strand approximately 1 cm anterior and superior to the previous strand for site three as well as site four. Four individual strands are now exiting the skin. We then proceed to make an accessory portal between sites two and three. Use a blade to incise only the skin.

same technique, we insert a second bone anchor in the fibula at the level of the lateral talar dome. The strands exit the anterolateral portal and one would again use a Micro SutureLasso to capture the individual strand approximately 1 cm anterior and superior to the previous strand for site three as well as site four. Four individual strands are now exiting the skin. We then proceed to make an accessory portal between sites two and three. Use a blade to incise only the skin.

Then employ a hemostat for blunt dissection until you have probed the inferior extensor retinaculum. Use an arthroscopic probe to gather the strands subcutaneously with all strands exiting the accessory portal. Release the extremity from distraction. With the assistant holding the foot in a dorsiflexed and everted position, hand tie the strands for each individual bone anchor to the appropriate tension. This will advance the anterior talofibular ligament, ankle capsule and inferior extensor retinaculum, and secure them to the anterior fibula. Do not cut the strands at this point. Make a separate 1 cm to 2 cm incision approximately 3 cm proximal to the distal fibula laterally in the midline of the bone.

The fibula should be visible. Using the 2.9 mm bioabsorbable anchor system (PushLock®, Arthrex), drill a hole into the fibula. Then direct a curved hemostat subcutaneously through the incision as close to the fibula as possible and exit the accessory portal where you tied the knots. Then use the hemostat to capture the strands and advance them proximally, exiting at the fibular incision. Secure the strands into the fibula using the 2.9 mm bioabsorbable anchor, applying additional tension to the sutures. This technique creates a double row construct using three suture anchors. We typically address extra-articular pathology, such as peroneal tendon pathology, after the lateral ankle stabilization procedure. We then supplement the regional block with 10 cc of 0.5% Marcaine plain proximal to the incisions.

Close the incisions with 3-0 nylon and apply a soft bandage. Postoperatively, have the patient utilize a controlled ankle motion (CAM) boot and begin protected weightbearing at three days post-op. Remove the sutures at two weeks post-op and have the patient begin formal physical therapy at the three week post-op mark. The patient continues to ambulate with the CAM boot up to the four-week point and transitions to an ankle sport brace and regular shoes at the fourth week. The patient utilizes the sports brace for an additional two weeks and when performing impact activities until the third month postoperatively.

incisions with 3-0 nylon and apply a soft bandage. Postoperatively, have the patient utilize a controlled ankle motion (CAM) boot and begin protected weightbearing at three days post-op. Remove the sutures at two weeks post-op and have the patient begin formal physical therapy at the three week post-op mark. The patient continues to ambulate with the CAM boot up to the four-week point and transitions to an ankle sport brace and regular shoes at the fourth week. The patient utilizes the sports brace for an additional two weeks and when performing impact activities until the third month postoperatively.

What The Literature Reveals About Ankle Arthroscopy

There has been an increase in the literature concerning arthroscopic or arthroscopic assisted lateral ankle stabilization. Discussing the use of a staple to repair the injured anterior talofibular ligament, Hawkins was the first to report utilizing ankle arthroscopy for the treatment of lateral ankle instability in 1987.10

There has been an increase in the literature concerning arthroscopic or arthroscopic assisted lateral ankle stabilization. Discussing the use of a staple to repair the injured anterior talofibular ligament, Hawkins was the first to report utilizing ankle arthroscopy for the treatment of lateral ankle instability in 1987.10

Maiotti and colleagues examined the use of arthroscopic thermal shrinkage for the treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability in 22 soccer players.11 More than 86 percent reported a good or excellent functional outcome at a mean follow-up of 42 months and the study authors noted that 18 of 22 patients had no evidence of ankle instability during the follow-up physical examination or on stress radiographs.

Maiotti and colleagues examined the use of arthroscopic thermal shrinkage for the treatment of chronic lateral ankle instability in 22 soccer players.11 More than 86 percent reported a good or excellent functional outcome at a mean follow-up of 42 months and the study authors noted that 18 of 22 patients had no evidence of ankle instability during the follow-up physical examination or on stress radiographs.

We have a keen interest in this technique and have reported our findings over the past several years. In 2013, Cottom and Rigby reported on the use of an all inside arthroscopic technique with two-anchor single row repair to address intra-articular pathology in 40 consecutive patients.6 The mean follow-up was 12 months. Authors noted a statistical difference in pre- and postoperative patient-reported outcomes. There were few complications, including deep venous thrombosis in one patient, neuritis of the intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerve in one patient and a distal fibular fracture in one patient. The mean return to weightbearing was 20.2 days.

Later in 2016, Cottom and colleagues reported on three different arthroscopic lateral ankle constructs and tested them in the lab on cadaveric specimens.12 The constructs tested were the all-inside arthroscopic Broström with two-anchor single row technique, an all-inside arthroscopic Broström with three-anchor double row technique and an all-inside arthroscopic Broström repair with a double row, four anchor knotless technique. Out of the three constructs tested, the arthroscopic Broström with a proximal suture anchor resulted in the highest load to failure. There was a statistical significant difference in this construct and the single row two-anchor construct that we previously described.

Later in 2016, Cottom and colleagues reported on three different arthroscopic lateral ankle constructs and tested them in the lab on cadaveric specimens.12 The constructs tested were the all-inside arthroscopic Broström with two-anchor single row technique, an all-inside arthroscopic Broström with three-anchor double row technique and an all-inside arthroscopic Broström repair with a double row, four anchor knotless technique. Out of the three constructs tested, the arthroscopic Broström with a proximal suture anchor resulted in the highest load to failure. There was a statistical significant difference in this construct and the single row two-anchor construct that we previously described.

A recent prospective report in 2017 by Cottom and coworkers reviewed 45 consecutive patients who had all-inside arthroscopic Broström lateral ankle stabilization with an additional suture anchor proximally.13 The average follow-up was 14 months. Study authors recorded pre- and postoperative American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) scores, Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores, Foot Function Index (FFI) and Karlsson–Peterson scores, and they showed statistically significant improvement at the final follow-up. Interestingly, the mean time to weightbearing postoperatively was 3.3 days in a CAM boot.

This is a drastic change from the original report by the same authors in three years prior. We feel that the increase in construct stability demonstrated in the biomechanical study allowed for earlier return to weightbearing, albeit protected weightbearing. This improvement in return to protected weightbearing shortens the time to initiate physical therapy and the ultimate return to regular activities.

This is a drastic change from the original report by the same authors in three years prior. We feel that the increase in construct stability demonstrated in the biomechanical study allowed for earlier return to weightbearing, albeit protected weightbearing. This improvement in return to protected weightbearing shortens the time to initiate physical therapy and the ultimate return to regular activities.

In Conclusion

Lateral ankle instability is present in 10 to 20 percent of the population who have experienced an ankle sprain. These patients often benefit from surgical repair. In our practice, we perform ankle stabilization with the use of ankle arthroscopy. This method has proven to improve patient-reported outcome measures significantly. The minimal incisions that we utilize and the biomechanical strength of the repair allow for early weightbearing and earlier return to activity than the literature reports with traditional open repair. When one perform arthroscopic repair properly, it can be a viable additional treatment method for patients with chronic lateral ankle stabilization.

Lateral ankle instability is present in 10 to 20 percent of the population who have experienced an ankle sprain. These patients often benefit from surgical repair. In our practice, we perform ankle stabilization with the use of ankle arthroscopy. This method has proven to improve patient-reported outcome measures significantly. The minimal incisions that we utilize and the biomechanical strength of the repair allow for early weightbearing and earlier return to activity than the literature reports with traditional open repair. When one perform arthroscopic repair properly, it can be a viable additional treatment method for patients with chronic lateral ankle stabilization.

Dr. Cottom is the Director of the Florida Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Center Fellowship in Sarasota, Fla. He is a Fellow of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. He is a consultant and speaker for Arthrex.

Dr. Plemmons is a Fellow of the Florida Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Center Fellowship in Sarasota, Fla. Dr. Plemmons is an Associate of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons.

References

- Shakked RJ, Karnovsky S, Drakos MC. Operative treatment of lateral ligament instability. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017; 10(1):113–21.

- Giovanni CW, Brodsky A. Current concepts: lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(10):854–66.

- Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, Zacchilli MA, Belmont PJ. The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010; 92(13):2279–84

- Colville M. Surgical treatment of the unstable ankle. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998; 6(6):368-377.

- Bell S, Mologne T, Sitler J. Twenty-six year results after Broström procedure for chronic lateral ankle instability. Am J Sports Med. 2006; 34(6):975–978.

- Cottom JM, Rigby RB. The “all inside” arthroscopic Broström procedure: a prospective study of 40 consecutive patients. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2013; 52(5):568-574.

- Hintermann B, Regazzoni P, Lampert C, Stutz G, Gächter A. Arthroscopic findings in acute fractures of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(3):345-51.

- Ferkel R, Chams R. Chronic lateral instability: arthroscopic findings and long-term results. Foot Ankle Int. 2007; 28(1):865–872.

- Cottom JM, Richardson PE. The “all inside” arthroscopic Broström procedure augmented with a proximal suture anchor: an innovative technique. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017; 56(2):408–11.

- Hawkins R. Arthroscopic stapling repair for chronic lateral instability. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1987; 4(4):875-883.

- Maiotti M, Massoni C, Tarantino U. The use of arthroscopic thermal shrinkage to treat chronic lateral ankle instability in young athletes. Arthroscopy. 2005; 21(6):751-757.

- Cottom JM, Baker JS, Richardson P, Maker J. A biomechanical comparison of 3 different arthroscopic lateral ankle stabilization techniques in 36 cadaveric ankles. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016; 55(6):1229-1233.

- Cottom JM, Baker, JS, Richardson PE. The “all inside” arthroscopic Broström procedure augmented with a proximal suture anchor augmentation: A prospective study of 45 consecutive patients. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016; 55(6): 1223-1228.

Additional References

14. Berlet G, Saar W, Ryan A, Lee T. Thermal-assisted capsular modification for functional ankle instability. Foot Ankle Clin North Am. 2002; 7(3):567-576.

15. Acevedo J, Mangone P. Arthroscopic lateral ankle ligament reconstruction. Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 2011; 10:111-116.

16. Kashuk K, Carbonell J, Blum J. Arthroscopic stabilization of the ankle. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1997; 14(3):459-478.

17. Corte-Real N, Moreira R. Arthroscopic repair of chronic lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2009; 30(3):213-217.

For further reading, see “Pertinent Insights On Ankle Arthroscopy” in the January 2013 issue of Podiatry Today, “Current Concepts In Ankle Arthroscopy” in the December 2007 issue, or “A Closer Look At The Use Of Arthroscopy In Foot And Ankle Surgery” in the supplement “Highlights from the 2017 Scientific Conference of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons” at https://www.podiatrytoday.com/files/acfas_supp_full.pdf .