ADVERTISEMENT

A Closer Look At The Benefits Of Dermoscopy

For the podiatric physician, a dermatoscope can be a valuable tool in differentiating pigmented and non-pigmented cutaneous presentations. This author offers pearls on using dermoscopy to diagnose various cutaneous disorders, malignant and non-malignant, as well as practical insights on obtaining a dermatoscope.

For the podiatric physician, a dermatoscope can be a valuable tool in differentiating pigmented and non-pigmented cutaneous presentations. This author offers pearls on using dermoscopy to diagnose various cutaneous disorders, malignant and non-malignant, as well as practical insights on obtaining a dermatoscope.

Dermoscopy is a noninvasive, in vivo technique, which clinicians primarily use to evaluate pigmented lesions and non-pigmented cutaneous disorders. A growing number of trained physicians are employing this technique to make an earlier diagnosis of skin cancer, leading to improved outcomes.

Dermoscopy takes the cutaneous examination deeper through a window into the dermis. Conventional cutaneous examination relies on careful inspection of the skin in a good light but is limited in depth because of the refractive index of the skin surface layer, which obscures the underlying dermal architecture. The dermatoscope polarizes reflected light to allow the examiner to see through the stratum corneum, visualizing the deep layers of epidermis and papillary dermis. This allows examination of the characteristic pigment and vascular patterns of the skin as well as the architecture of the upper dermal papillae and rete ridges of the skin and nail bed. Polarized light penetrates approximately 60 to 100 μm.1 Similar to the ophthalmoscopic examination, the dermoscopy examination can open a clinical window to visualize deeper disease processes.

Dermoscopy can become a tool to enhance your diagnostic acumen. This tool detects features in the skin that can lead to a more confident diagnosis. When coupled with digital images, a dermatoscope can help detect malignant changes over time.

Your patients will see your diagnostic skills in a new light and appreciate you adding dermoscopy to your practice armamentarium. Nearly every patient has a lesion or two that needs diagnosis, and a name the patient can understand. With practice, your dermoscopic eye becomes as fast as your clinical eye.2 There is a certain wow factor for both the examiner and patient when they are able to see a skin disorder up close through a dermatoscope coupled with digital photography. For the first time, we are able to visually link the macroscopic presentation with the diagnostic microscopic epidermal and dermal architecture of a lesion.

Your patients will see your diagnostic skills in a new light and appreciate you adding dermoscopy to your practice armamentarium. Nearly every patient has a lesion or two that needs diagnosis, and a name the patient can understand. With practice, your dermoscopic eye becomes as fast as your clinical eye.2 There is a certain wow factor for both the examiner and patient when they are able to see a skin disorder up close through a dermatoscope coupled with digital photography. For the first time, we are able to visually link the macroscopic presentation with the diagnostic microscopic epidermal and dermal architecture of a lesion.

Dermoscopy is fast becoming the podiatrist’s ophthalmoscope.3 I hope that acquainting podiatrists with the dermoscopic features of several lower extremity conditions will help lead to earlier and more accurate cutaneous diagnoses.

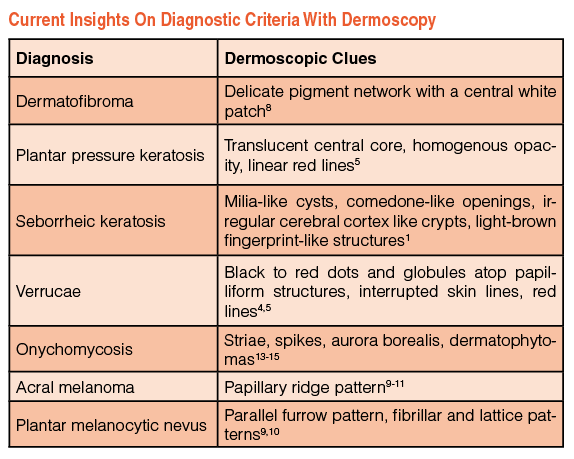

However, it is important to recognize that the visualization of structures within the epidermis and papillary dermis using dermoscopy has generated new terminology and clinical criteria for many cutaneous lesions. Just as radiography and diagnostic ultrasonography have their own unique terminology, it is imperative that the budding “dermoscopist” becomes proficient at identifying the characteristic colors, patterns and structures of benign and malignant lesions in order to synthesize a correct diagnosis.1 Exploring the extensive dermoscopy literature that fills textbooks and atlases is essential to develop dermoscopy skills. For now, let us focus on several disorders we see every day.

Using Dermoscopy To Assess Selected Common Disorders

Using Dermoscopy To Assess Selected Common Disorders

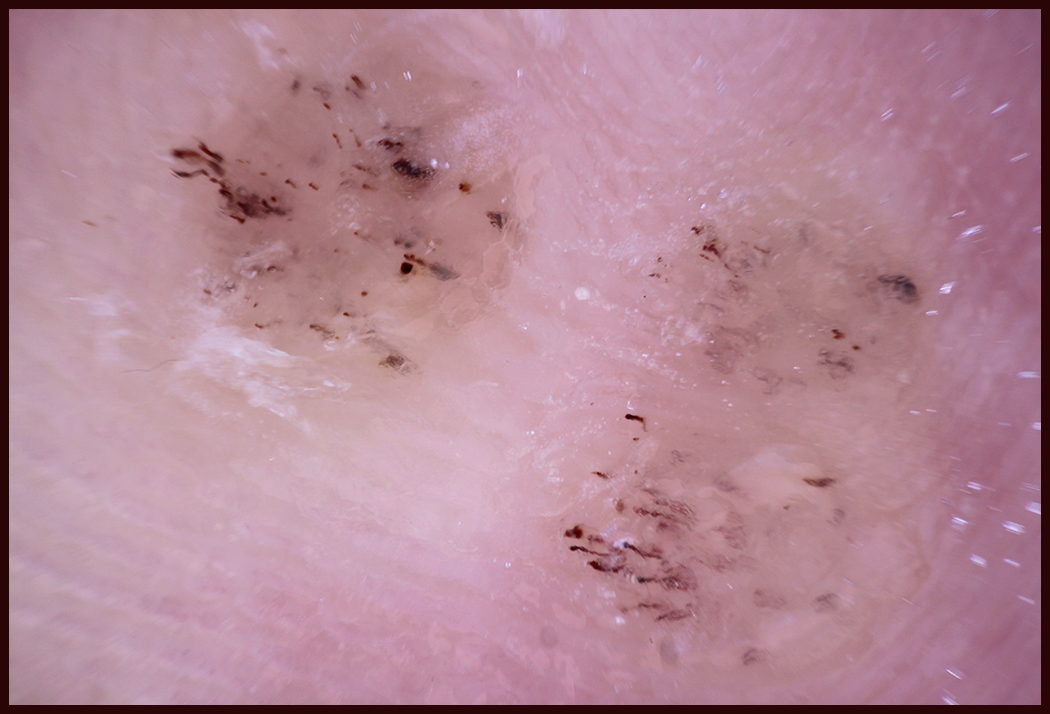

Patients often present with a plantar lesion and we wonder if it is a verruca or a plantar keratosis. Questions may arise whether the verruca is responding to treatment as expected or has completely resolved with our treatments. Is an apparent chronic and recurrent verruca actually just scar tissue from previous treatment? A dermatoscope with or without an ultrasound gel contact medium can help answer the question. Clinically, verrucae are hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into mosaic plaques that we can easily appreciate with dermoscopy.

The distinctive dermoscopic features of verrucae plantaris are reddish lines, loops and dots atop multiple, prominent, densely packed, white-haloed dermal papillae. These distinctive dermoscopic features correlate to the hemorrhage within thrombosed capillaries atop the hypertrophied papillae that are visible histologically.4 In addition, plantar verrucae appear as well-defined disruptions of the normal dermatoglyphic pattern with flattening and obliteration of the normal parallel papillary ridges and furrows. One can be assured of complete resolution of plantar verrucae after the parallel ridges and furrows pattern return, and the wart’s prominent dermal papillae, red lines, loops and dots have disappeared.

Plantar pressure keratoses exhibit a translucent or white central core or nucleus without dermal papillae. With intractable plantar keratoses resulting from abnormal pressure and friction, they may present with scattered parallel red and black lines of corneal hemorrhage.5

What Are The Dermoscopic Features Of Seborrheic Keratoses?

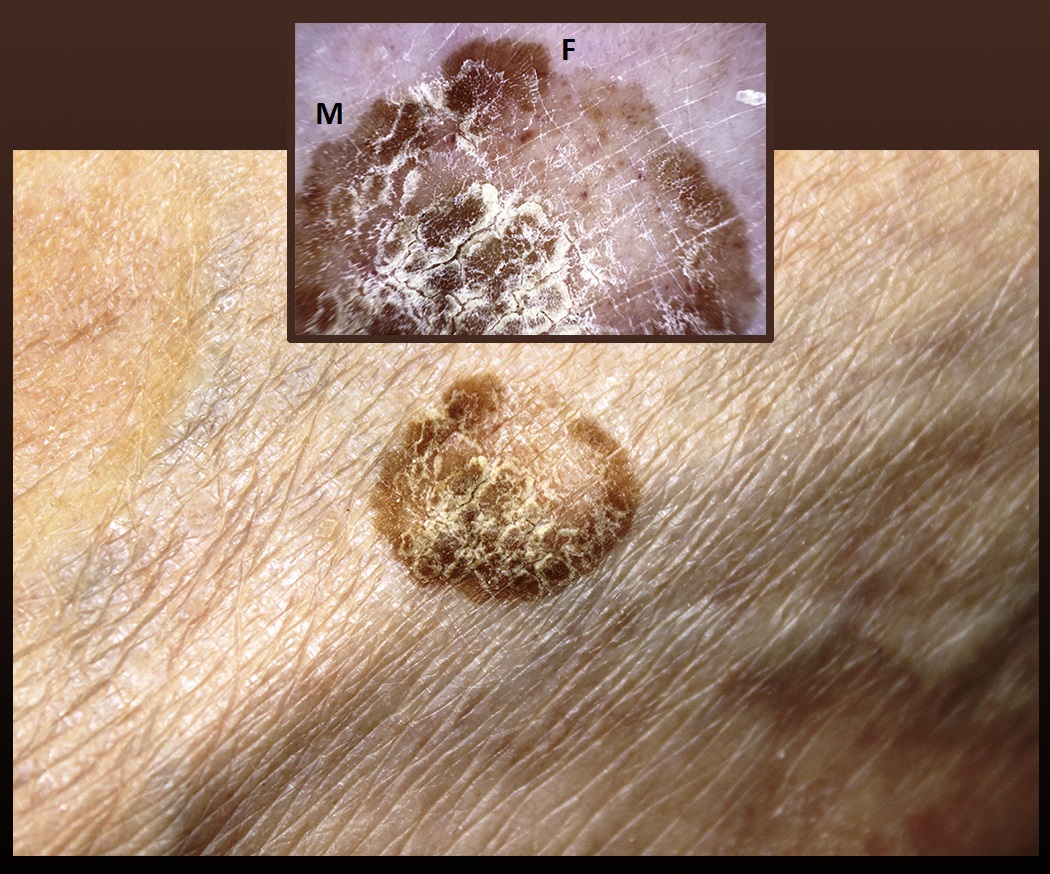

Patients often present with abnormal cutaneous lesions on the lower legs, ankles and feet. Among the most prevalent are seborrheic keratoses. They appear as well demarcated round to oval hyperkeratotic plaques with a verrucous surface and stuck-on appearance. Seborrheic keratoses are benign epidermal tumors that represent accumulations of immature keratinocytes. They typically develop after age 50 and may have a hereditary predisposition. Ultraviolet light exposure and the human papilloma virus have been implicated as possible causes.6 The sudden increase in the size and number of itchy seborrheic keratoses on the chest and back over the previous three months is known as the sign of Leser-Trélat.6 It is a worrisome sign of internal malignancy.

The classic dermoscopic criteria of seborrheic keratoses includes milia-like cysts and comedo-like openings that may not occur on the lower limbs where follicular openings are sparse. Additional dermoscopic features such as fissures, hairpin blood vessels, sharp demarcation and moth-eaten borders also characterize seborrheic keratoses. The identification of a pigmented network-like structure is helpful to increase the accuracy of diagnosis. Peripheral fingerprint-like structures are delicate, thin, light brown, parallel lines that do not interconnect to form a true grid.

The classic dermoscopic criteria of seborrheic keratoses includes milia-like cysts and comedo-like openings that may not occur on the lower limbs where follicular openings are sparse. Additional dermoscopic features such as fissures, hairpin blood vessels, sharp demarcation and moth-eaten borders also characterize seborrheic keratoses. The identification of a pigmented network-like structure is helpful to increase the accuracy of diagnosis. Peripheral fingerprint-like structures are delicate, thin, light brown, parallel lines that do not interconnect to form a true grid.

Epidermal ridges or so-called fat fingers and sulci (fissures) may create a characteristic cerebriform pattern. These invaginations are filled with keratin, creating crypts.1 Seborrheic keratoses may be pigmented and at first glance, one would confuse them with nevi or even melanoma. Dermoscopic examination is often reassuring.7

What Dermatofibromas Look Like Under Dermoscopy

It is not uncommon to encounter a dermatofibroma clinically. It presents as a firm, button-like, non-painful papule to nodule on the lower legs that typically measures 3 to 7 mm but can reach 3 cm. They seem to erupt spontaneously, perhaps after the trauma of shaving or an irritated insect bite. Dermatofibromas represent a benign, reactive fibrous hyperplasia with exuberant fibrotic repair. They develop most often on the lower legs of females, developing slowly over months to years and persisting indefinitely.

Where there is sufficiently thick underlying subcutaneous fat, these firm, dome-shaped lesions respond to lateral pinching by dimpling inward. Dermoscopic examination regularly detects a light brown pseudo-network of pigmented rete ridges. This delicate network is characterized by light brown mesh. A central white scar-like patch is visible in the majority of dermatofibromas.8

What You Should Know About Detecting Plantar Nevi

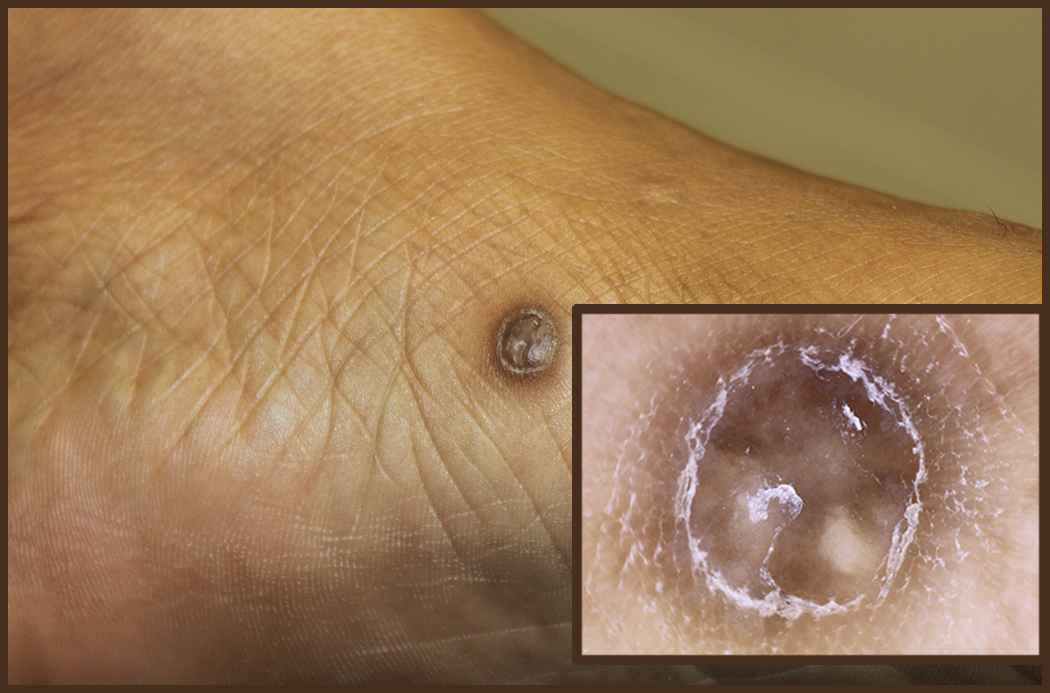

Plantar pigmented lesions are prevalent and call for dermoscopy screening of at least the “ugly ducklings” to reduce a potentially lethal diagnostic delay. The first step beyond the basic A-E pigmented lesion evaluation is to rule out the presence of the pigmented ridge pattern that would warrant biopsy. Normally, the pigment on the soles and palms is arranged in distinctive benign patterns. The most common benign plantar pattern is the parallel furrow pattern. Normal melanocytes stay in the narrow furrows but dysplastic melanocytes invade the wider adjacent papillary ridges.3

Additional benign plantar pigment patterns are the fibrillar and lattice patterns that may evolve over time from the parallel furrow pattern. The benign fibrillar pattern starts with the parallel furrow pigment, which develops regularly arranged fine filaments that obliquely cross over but do not fill the wider papillary ridges, giving the fine filaments the appearance of a feather. The benign lattice pattern is similarly arranged but the filaments cross the papillary ridge perpendicular to the furrows.

These variations on the benign parallel furrow pattern seem to depend on the pressure patterns of the sole that develop over time. It is helpful to realize that the ridges are several folds wider than the furrows and they are regularly studded by the white dots representing the ubiquitous eccrine gland openings. There are a number of clinical variations of these patterns but ruling out the malignant parallel ridge pattern is an important first step in differentiating melanoma versus benign melanocytic nevus.

These variations on the benign parallel furrow pattern seem to depend on the pressure patterns of the sole that develop over time. It is helpful to realize that the ridges are several folds wider than the furrows and they are regularly studded by the white dots representing the ubiquitous eccrine gland openings. There are a number of clinical variations of these patterns but ruling out the malignant parallel ridge pattern is an important first step in differentiating melanoma versus benign melanocytic nevus.

Clinicians can evaluate lower extremity pigmented lesions beyond the plantar nevi with additional diagnostic clues of dermoscopic melanoma specific structures as described by Marghoob and others.1,9-11 Like the interpretation of radiographs, magnetic resonance images (MRI), computed tomography (CT) and diagnostic ultrasound, the specific diagnostic clues of dermoscopy are defined and correlate with the underlying histopathology. Further study is essential to become familiar with diagnostic patterns that can characterize the disorders we see in practice.

Can Dermoscopy Be Helpful In Diagnosing Onychomycosis?

Many abnormal toenails that we presume to be clinically mycotic nails are actually dystrophic nails caused by microtrauma and not a fungal infection. Even though fungal cultures remain necessary to perform an etiological diagnosis and are required by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as evidence of drug efficacy, their lower sensitivity and higher cost limit their clinical usefulness. The KOH wet mount preparations and dermatophyte test medium cultures are no longer reimbursable for non-mycologists. They are specific for dermatophytes but carry a low sensitivity as well as being highly operator dependent. The KOHs require access to a microscope and currently a certified technologist must perform the test. Pathologist interpreted periodic acid-Schiff tests and Grocott’s methenamine silver stains are very sensitive, but can cost $148 per test.12

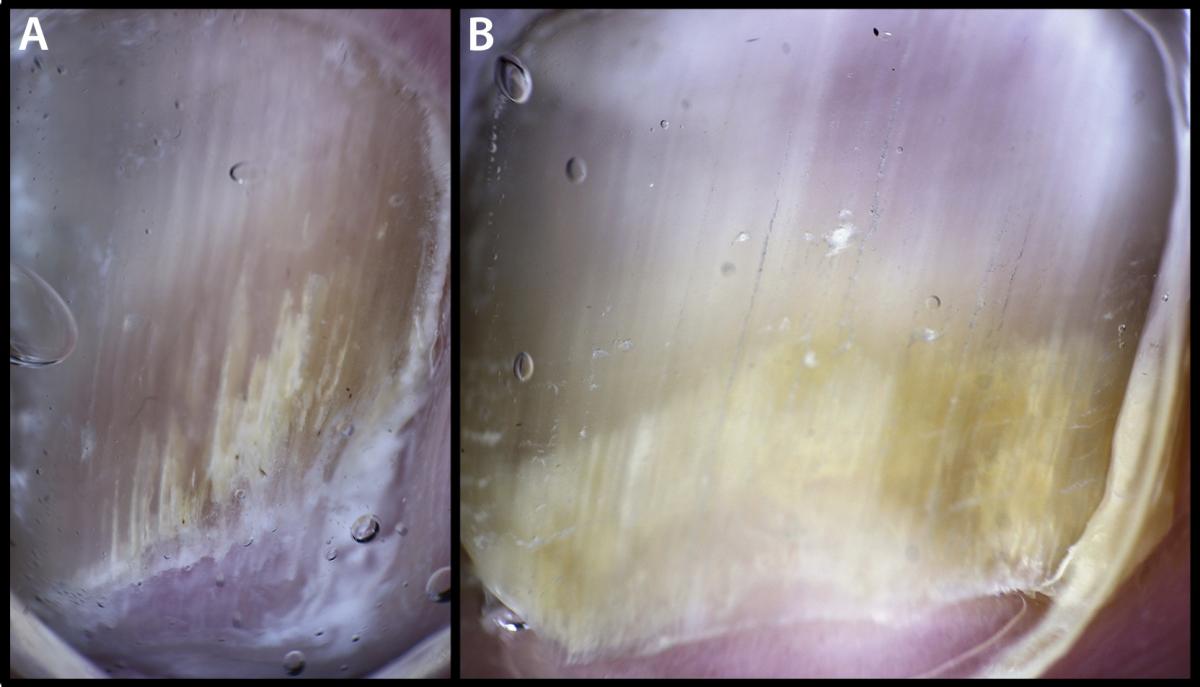

Authors have described the dermoscopic features of onychomycosis.13-15 These features correlate to fungal test results. Short spikes extending proximally from the hyponychial space along with onycholysis are characteristic of onychomycosis. One can often detect these initial changes in onychomycosis with contact dermoscopy coupled to the nail plate with ultrasound gel. The dermatophytic spikes may extend proximally, tunneling under the nail plate along the nail bed grooves as the infection progresses. This dermoscopic evidence of mycotic nail bed infection widens and lengthens into longer yellow striae that extend proximally along the longitudinal rete furrows of the nail bed.

Irregular distal subungual termination and subungual hyperkeratoses also develop. Over time, one may see a so-called “aurora” or “aurora borealis” pattern of many short and centrally longer spikes emerge.14,16 In more severe longstanding cases, a collection of subungual mycotic keratitis may turn into dermatophytoma. These additional features are also significantly associated with positive mycology tests. Typically, multiple sensitive dermoscopic signs of onychomycosis are present in each mycotic nail unit. The most sensitive signs are striae, spikes, aurora borealis and dermatophytoma. In addition, authors have reported irregular termination of the nail plate, onycholysis and opacity as well as subungual ruinous aspect, subungual black dots or globules, and dry or scaling adjacent skin in cases of onychomycosis.13-15

Irregular distal subungual termination and subungual hyperkeratoses also develop. Over time, one may see a so-called “aurora” or “aurora borealis” pattern of many short and centrally longer spikes emerge.14,16 In more severe longstanding cases, a collection of subungual mycotic keratitis may turn into dermatophytoma. These additional features are also significantly associated with positive mycology tests. Typically, multiple sensitive dermoscopic signs of onychomycosis are present in each mycotic nail unit. The most sensitive signs are striae, spikes, aurora borealis and dermatophytoma. In addition, authors have reported irregular termination of the nail plate, onycholysis and opacity as well as subungual ruinous aspect, subungual black dots or globules, and dry or scaling adjacent skin in cases of onychomycosis.13-15

Differentiating Between Onychomycosis And Microtraumatic Nail Dystrophy

About half of abnormal toenails are not actually mycotic. By utilizing dermoscopy, one can readily differentiate between microtraumatic nail dystrophy and distal subungual and lateral onychomycosis. Point of care diagnosis makes for more accurate diagnoses as well as reduced laboratory costs. The detection of striae, spikes, aurora borealis or dermatophytomas makes the diagnosis of onychomycosis complete.

At least for topical therapy of mild to moderate onychomycosis, treatment can begin immediately without laboratory delay. One can confirm the diagnosis of moderate to severe onychomycosis, requiring systemic therapy, via laboratory tests while waiting for baseline hepatic function panel results. One should suspect microtraumatic nail dystrophy if the onychomycosis striae, spikes, aurora borealis or dermatophytomas features are absent, and there is transverse onycholysis with nail plate opacity. Black dots or globules are additional indicators of microtrauma.13,14

Pertinent Pearls On Using Dermoscopy For Splinters

Removal of small, painful plantar splinters can be challenging. A minor superficial foreign body may be better felt than seen. The dermatoscope greatly facilitates localization of the offending splinter whether it be wood, metal, plastic or hair.

Once one has localized, circumscribed and prepped the area in question, the clinician can use a tissue nipper to obliquely scribe a superficial incision of epidermis around the foreign body and remove a conical plug of keratin containing the entire splinter. The tissue nipper is less likely to cause additional damage to the skin as opposed to the #15 blade and forceps. Subsequent inspection with the dermatoscope along with the lessened tenderness will help ensure the complete removal of the splinter. One can inspect the excised plug itself with a dermatoscope to help analyze the foreign body.

Key Considerations When Purchasing A Dermatoscope And Seeking Reimbursement

Key Considerations When Purchasing A Dermatoscope And Seeking Reimbursement

Dermatoscopes can range in price from about $375 to $1,400 for a fine, handheld instrument. Color enhancement features and USB charging, rather than battery power, add to the cost. It is wise at first to purchase a midrange dermatoscope that at least has cross-polarization. Some dermatoscopes magnetically attach to a smartphone to record the dermoscopic image for analysis and reference. Some electronic health records allow clinicians the capability to upload the digital image immediately to the patient’s electronic chart. This feature is akin to having a radiographic record to monitor pathology over time. Dermoscopy is a dynamic examination like diagnostic ultrasound and fluoroscopy. Capturing dermoscopic images greatly facilitates interpretation and study. Like ophthalmoscopy, dermoscopy requires training experience and especially daily clinical use to maximize the diagnostic usefulness.

Since dermoscopy clearly adds diagnostic value, it is reasonable and appropriate that dermoscopy documentation in the record elevates the complexity of the examination and increases the data review points that support the higher evaluation and management codes. Dermoscopy readily focuses the visit on additional problems that elevate the assessment. The history of the lesion being examined with the dermatoscope also adds to the history of the present illness. Expanding the basic assessment with a dermoscopic diagnosis leads to a broader plan to help the patient.17

Dr. Bodman is an Associate Professor at the Kent State University College of Podiatric Medicine. He is board-certified by the American Board of Podiatric Medicine.

The author acknowledges the contributions of Joan Lannoch, the Senior Graphic Designer at Kent State University College of Podiatric Medicine.

References

- Marghoob A, Usatine RP, Jaimes N. Dermoscopy for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(7):441-450.

- Markowitz O. Dermoscopy update and noninvasive imaging devices for skin cancer: report from the Mount Sinai Winter Symposium. Available at https://www.mdedge.com/authors/orit-markowitz . Accessed January 4, 2017

- Bodman MA. Essential insights on dermoscopy of plantar pigmented lesions. Podiatry Today. 2015; 25(5):54–61.

- Zalaudek I. Dermoscopy in general dermatology. In Marghoob AA, Malvehy J, Braun RP (eds.): Atlas of Dermoscopy, Second Edition. Informa Healthcare, Essex, UK, p. 327.

- Bae JM, Kang H, Kim HO, Park YM. Differential diagnosis of plantar wart from corn, callus and healed wart with the aid of dermoscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(1):220-2.

- Hafner C, Vogt T. Seborrheic keratosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6(8):664-77.

- Braun RP, Rabinovitz HS, Krischer J, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented seborrheic keratosis: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(12):1556-60.

- Zaballos P, Puig S, Llambrich A, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of dermatofibromas: a prospective morphological study of 412 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2008; 144(1):75–83.

- Bristow IR, de Berker DA, Acland KM, Turner RJ, Bowling J. Clinical guidelines for the recognition of melanoma of the foot and nail unit. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010; 1(3):25.

- Saida T, Koga H, Tsao H, Corona R. Dermoscopy of pigmented lesions of the palms and soles. UpToDate. Available at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermoscopy-of-pigmented-lesions-of-the-palms-and-soles . Accessed 1/10/17.

- Bristow IR, Bowling J. Dermoscopy as a technique for the early identification of foot melanoma. J Foot Ankle Res. 2009; 12(2):14.

- Mikailov A, Cohen J, Joyce C, Mostaghimi A. Cost-effectiveness of confirmatory testing before treatment of onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(3):276-81.

- Jesus-Silva MA, Fernandez-Martinez R, Roldan-Marin R, Arenas R. Dermoscopic patterns in patients-results of a prospective study including data of potassium hydroxide (KOH) and culture examination. Dermatol Practical Conceptual. 2015; 5(2):5

- Piraccini R, Balestri R, Starace GR. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. JEADV. 2013, 27(4):509-513.

- Nakamura RC, Costa MC. Dermatoscopic findings in the most frequent onychopathies: descriptive analysis of 500 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2012; 51(4):483-496.

- Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Onychomycosis: a review. J Fungi. 2015; 1:30-43.

- Lallas A, Gicomel J, Argenziano G, Garcia-Garcia B, Gonzalez-Fernandex D, Zalaudek I, Vazque-Lopez F. Dermoscopy in general dermatology: practical tips for the clinician. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(3):514-526.