ADVERTISEMENT

Can Autologous Fat Grafting Help Address Fat Pad Atrophy In Patients With Diabetes?

The feet support the entire body and are subject to repetitive mechanical trauma throughout a lifetime, thereby propagating the atrophy of the plantar fat pad. Fat pad degradation is a common cause of callus formation, pain and ulceration.

The feet support the entire body and are subject to repetitive mechanical trauma throughout a lifetime, thereby propagating the atrophy of the plantar fat pad. Fat pad degradation is a common cause of callus formation, pain and ulceration.

Patients with diabetes comprise a large subset of patients with foot complications due to their higher incidence of elevated pedal pressures coupled with diabetic neuropathy and soft tissue glycosylation. This can lead to ulcer formation and ultimately progress to the devastating consequences of amputation.1-4 Currently, podiatrists are addressing pain from fat pad atrophy through the use of extrinsic foot padding or extra-depth diabetic shoes with multidensity Plastazote inserts with the goal of reducing local pressure as well as tissue breakdown.5

However, patient adherence with extrinsic devices is challenging because the devices don’t fit in their “favorite” shoes. In addition, patients may experience increased friction, irritation and breakdown at a different location on the foot due to the thickness of the device in the shoe. The patient must replace the device as soon as it breaks down but the breakdown often goes unnoticed.

Autologous fat grafting to areas of plantar fat pad atrophy may reduce plantar pressures and thus serve as a treatment for metatarsalgia, callus prevention and possibly ulcer prevention in patients with diabetes. Patients with diabetes often develop peripheral neuropathy, which can mask situations that would be painful in those without diabetes and may lead to soft tissue injury of the feet. Diabetic foot wounds are difficult to heal due to preexisting vasculopathy and patient non-adherence with offloading. In addition, the immune system of patients with diabetes becomes compromised as the disease state becomes prolonged. The potential vasculopathy, neuropathy and immunodeficiency in patients with diabetes make this population more prone to developing infected ulcers on the feet as well as developing serious complications, such as osteomyelitis, that often lead to amputation.6

Typically, one may best treat ulceration due to bone prominence by surgical resection of the prominent bone. However, transfer lesions and re-ulceration are common complications after diabetic foot ulcer surgery.5 Also bear in mind that some patients may not be medically stable or are at higher risk for an acute Charcot event post-surgery, making an aggressive osseous surgical procedure inadvisable. While fat grafting along with bony surgery may be the best case scenario for optimizing outcomes in diabetic forefoot surgery, there is a population of patients that may benefit from fat grafting alone to treat fat pad atrophy via a less invasive manner that can potentially limit ulceration.

Reviewing The Research On Fat Grafting

Over 20 years ago, Chairman published the first paper on fat grafting to the feet.7 Fifty patients had autologous fat grafting at the time of bone surgery and there were subjective determinations on pain relief. Only a few patients either did not respond to the fat grafting or required another round of fat grafting.

Despite the quoted high success rate of 98 percent from Chairman’s study, fat grafting to the feet did not “take off” as a treatment of choice for patients with fat pad atrophy as anecdotal reports determined that the grafted fat does not last.7 However, to date, no controlled clinical trials utilizing objective measures have determined the efficacy of fat grafting to the foot without bony surgery. In addition, Chairman utilized fat from the calf, which is not standard in fat grafting procedures, and did not describe the exact processing of the fat.7 Over the past 20 years, knowledge in fat grafting has advanced significantly and newer methods and processes can aid in fat graft retention.8

Despite the quoted high success rate of 98 percent from Chairman’s study, fat grafting to the feet did not “take off” as a treatment of choice for patients with fat pad atrophy as anecdotal reports determined that the grafted fat does not last.7 However, to date, no controlled clinical trials utilizing objective measures have determined the efficacy of fat grafting to the foot without bony surgery. In addition, Chairman utilized fat from the calf, which is not standard in fat grafting procedures, and did not describe the exact processing of the fat.7 Over the past 20 years, knowledge in fat grafting has advanced significantly and newer methods and processes can aid in fat graft retention.8

Surgeons have attempted other methods to add cushioning to the forefoot. Rocchio published a case series demonstrating the use of an acellular dermal allograft in the foot with some success.9 Twenty-two patients, five of whom had diabetes, had allograft insertion into the forefoot. One of these patients developed an infection. Any procedure requiring an open incision, suture material and undermining of natural septae to make room for a foreign material may increase the risk of complications and be suboptimal. Rocchio only used ultrasound for objective measurement of tissue thickness retention and only two people had follow-up at a year. More long-term studies with assessment of foot pressures before and after treatment would be helpful to determine the benefit of this treatment option.

Most of the data on augmenting the forefoot fat pad has focused on utilizing injectable materials such as silicone. Injected liquid silicone can increase plantar tissue thickness and decrease plantar pressure over at least a one-year period.10 Researchers have also found that injected liquid silicone stimulates some proliferation of surrounding collagen fibers.10 However, after two years, the cushioning ability of silicone diminished while plantar pressure increased. In theory, injections of silicone might be necessary on a yearly basis.

Another potential adverse event of silicone is its potential to migrate and not remain in the allocated fat pad position.11 Although migration appears to be asymptomatic, one might detect microscopic droplets in the groin lymph nodes. In patients with diabetes, silicone may be at risk for infection as a foreign body and difficult to remove, requiring large areas of debridement. Other fillers used by podiatrists off-label include hyaluronic acid or poly-L-lactic acid.

Currently, there is no data on the safety of hyaluronic acid and poly-L-lactic acid in the foot. Fillers can be very costly with 1 cc of product sometimes costing over $500 in our practice. Injecting an entire forefoot with temporary filler can be cost-prohibitive for patients with significant atrophy. In addition, some fillers are reconstituted with saline. Accordingly, as patients ambulate, they may disperse the product to other areas of the foot, leading to undesirable consequences. Other side effects of some fillers are granulomas, which may leave scar tissue and require excision or treatment with other agents.

What You Should Know About Pre-Op Considerations

At the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, we have a comprehensive program combining the expertise of podiatry, plastic surgery and stem cell biology to investigate the use of autologous fat on the forefoot and heel in healthy adults and those with diabetes. We currently have five prospective institutional review, board-approved clinical trials investigating fat grafting on the feet.

Patient selection is an important part of screening patients for this procedure. Podiatrists do not routinely perform fat grafting or have expertise in this area, and plastic surgeons rarely understand the biomechanics of the foot and who would benefit the most from the procedure. Therefore, having a team of experts to examine the foot and perform the procedure optimizes care for these patients. In our practice, the rigid cavus foot and semi-rigid cavus foot are the most common foot types presenting with metatarsalgia pain from fat pad atrophy. In our patients with diabetes, their rigid cavus forefoot “aching” metatarsalgia pain may be complicated by neuropathic “burning” type pain. In our experience so far, patients with diabetes with true aching pain versus neuropathic pain and non-diabetic patients suffering from fat pad atrophy pain with a rigid or semi-rigid cavus foot with minimal orthopedic deformities aside from flexible hammertoes seem to benefit the most from the fat grafting.

The flexible cavus foot or flexible pronated foot that has had cortisone injection and/or neuroma excision are other foot types that we commonly see in our clinic for our studies. We have also noted pain relief in these foot types after the fat grafting procedure. However, feet with severe deformities such as feet with significant bunions and rigid hammertoe formation, regardless of pronated or cavus foot type, have not experienced as much benefit post-injection. In addition, feet with plantar declinated metatarsals and underlying intractable plantar keratosis formation have had no benefit from the fat injections. These patients with severe forefoot deformities represent the group that would likely benefit from the combined approach of osseous surgery with fat grafting as proposed by Chairman.7 Stem cell characteristics of the fat from individuals (i.e. healthy adults of different ages or patients with diabetes) may influence fat retention and overall improvement in pain after the procedure. Our clinical trials will serve to answer these questions and more.

The flexible cavus foot or flexible pronated foot that has had cortisone injection and/or neuroma excision are other foot types that we commonly see in our clinic for our studies. We have also noted pain relief in these foot types after the fat grafting procedure. However, feet with severe deformities such as feet with significant bunions and rigid hammertoe formation, regardless of pronated or cavus foot type, have not experienced as much benefit post-injection. In addition, feet with plantar declinated metatarsals and underlying intractable plantar keratosis formation have had no benefit from the fat injections. These patients with severe forefoot deformities represent the group that would likely benefit from the combined approach of osseous surgery with fat grafting as proposed by Chairman.7 Stem cell characteristics of the fat from individuals (i.e. healthy adults of different ages or patients with diabetes) may influence fat retention and overall improvement in pain after the procedure. Our clinical trials will serve to answer these questions and more.

A Closer Look At The Authors’ Surgical Protocol

We perform the fat grafting procedure on an inpatient basis with no need for post-op non-weightbearing. Most patients we see live active lifestyles and being off work for four to six weeks, or completely off their feet are not viable options. For patient safety concerns, we do not perform fat grafting on patients who have had prior foot surgery within the past six months or require anticoagulation that cannot stop preoperatively.

Patients receive local anesthesia to numb the abdomen or flanks, and the foot/feet. We utilize a tibial nerve block and forefoot Mayo block utilizing a 1:1 Xylocaine/Marcaine plain mixture. One can use ethyl chloride spray to cool the foot prior to injections to ease pain. We perform this procedure for all patients, including patients with diabetic neuropathy.

We perform the fat grafting procedure with small extraction cannulas and injection cannulas that require no sutures. We use Steri-Strips for all sites. In regard to fat processing, we utilize a centrifuge and employ the standard Coleman technique.8 The fat after harvesting goes into a centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for three minutes and then the aqueous portion drains and the oil portion wicks off. One transfers the fat from 10 cc to 1 cc syringes for injection. We send a portion of the extracted fat to a stem cell lab for analysis in order to correlate stem cell characteristics with results over time. If patients have had prior dorsal incisions to remove neuromas, we routinely inject from a dorsal approach first to cushion between the metatarsals and then from two locations on the plantar surface of the foot to lay fat down with microdroplets in a cross-hatch pattern to avoid lakes of fat or over-injection. On average, we inject 4 to 6 cc of fat per foot.

Postoperatively, patients should limit ambulation for the first four weeks. Patients can shower and get the bandages wet within the first 24 hours. However, we give them instructions to stand on a shower pad, towel or wear flip-flops in the shower to avoid walking barefoot. The patient must wear a cushioned, supportive sneaker, which we modify with padding to promote offloading of the grafted areas at the time of the procedure. The patient may participate only in activities of normal daily living with no excessive aerobic activity. Standing or walking on the feet is limited to 15 minutes per hour at most for the first four weeks. Patients may manage postoperative pain with Tylenol. Mild bruising of the abdomen and feet is to be expected.

Preliminary Insights From The Authors’ Study Data

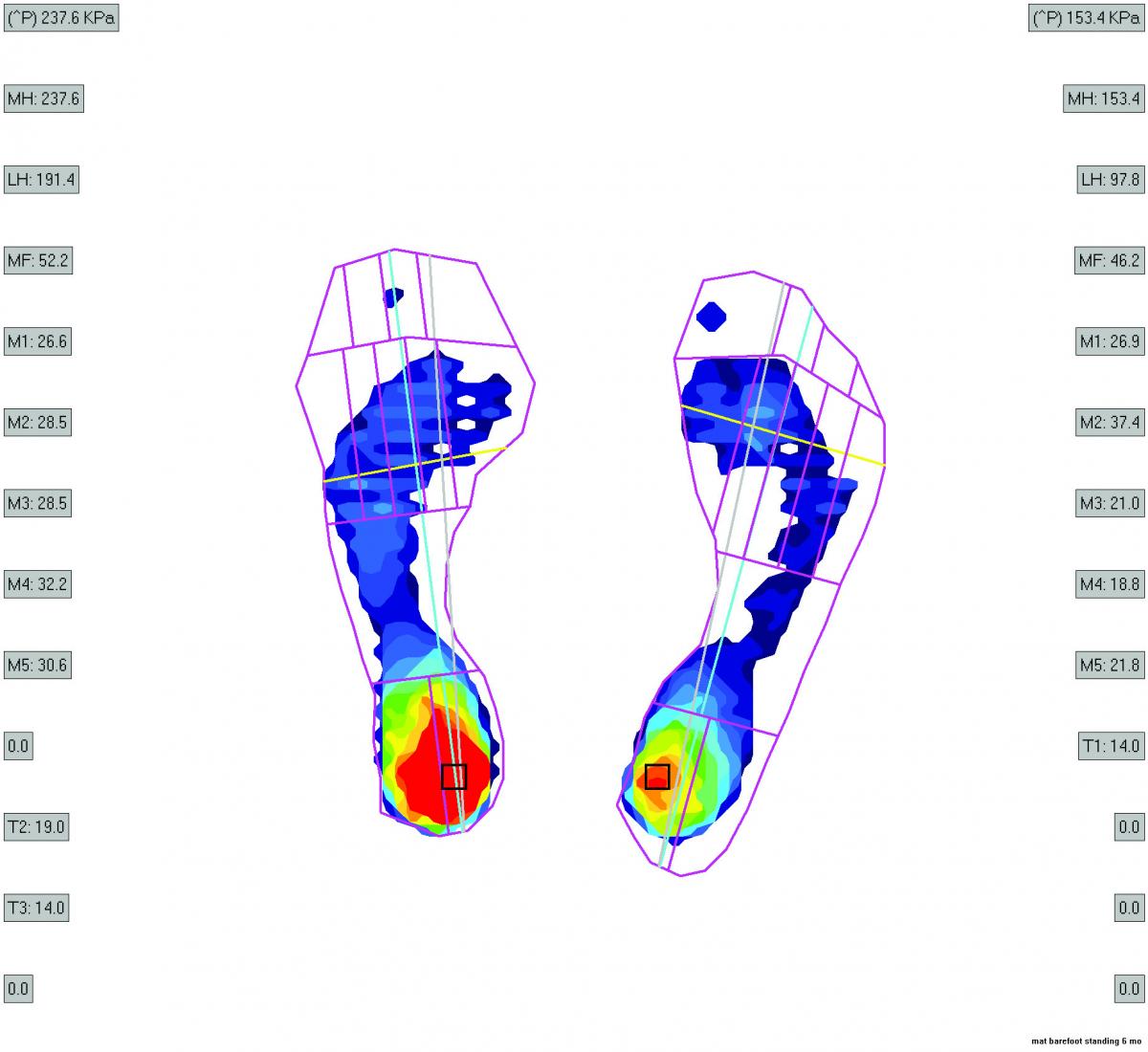

Preliminary analysis of our clinical trial data demonstrates statistically significant improvement in pain and quality of life at one year after treatment.12 Interestingly, we noted an increase of foot pressures (via pedobarograph assessment) in our control group. Control group patients had conservative management for a year and then crossed over into the fat grafting group. These findings indicate that at the very least, fat grafting may prevent worsening of pain and increased foot pressures over time due to fat pad atrophy.

Despite the significant improvements in quality of life for many of our patients two years out, we continue to encourage our patients to wear sensible, supportive and cushioned shoes once patients are pain free. They may wear high heels and less supportive shoes but in moderation. Many of our patients have returned to a more active lifestyle postoperatively. They return to their passions of hiking, cycling, exercise walking and report even walking the malls or grocery store more comfortably.

We are still determining what happens to the fat after injection. We hypothesize that as patients ambulate more on the fat grafts, they may redistribute pressure to offload the bone so it can heal, resulting in long-term pain relief. We currently have an ongoing National Institutes of Health-funded clinical trial utilizing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess the volume of fat in the foot before and after fat grafting.

We have experienced very few complications with the fat grafting procedure. If patients experience the sensation of lumpiness under the metatarsal, we encourage them to massage the foot gently, which has resulted in resolution over several weeks. A few of our patients have noted transient heel pain postoperatively as they compensated their gait and aggravated a preexisting plantar fasciitis or encouraged abnormal musculotendinous traction on the calcaneal bone with their over-cautious and abnormal gait. Although ambulation is permissible within reason, we emphasize for four to six weeks postoperatively a slower, proper, heel to toe gait in addition to non-weightbearing range of motion exercises for the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia. These findings further validate the importance of proper podiatric management of these patients in coordination with those who have plastic surgery expertise.

In Conclusion

The preliminary results of our studies are encouraging and hopefully may lead to a reduction in the cost of ulcer treatment in patients with diabetes. Perhaps fat grafting may prove to be an alternative option combating the challenges of maintaining specialized extrinsic padding, custom diabetic shoe gear and issues with patient offloading adherence. Augmenting the plantar fat pad not only has the potential to benefit patients with diabetes but it could also be useful in geriatric patients, wounded warriors with amputations (who have differential loading of their remaining lower extremity), athletes and cosmetic surgery patients who prefer high-heeled shoes over more practical footwear and have significant metatarsal pain from plantar fat pad atrophy.

Currently, fat grafting is considered a cosmetic procedure and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) do not reimburse for it. We are hopeful that our data will lead to reimbursable treatment for patients that suffer from the debilitating condition of fat pad atrophy.

Beth Freeling Gusenoff, DPM, is a board-certified podiatric surgeon and a Clinical Assistant Professor of Plastic Surgery in the Department of Plastic Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh.

Jeffrey Gusenoff, MD, is an Associate Professor of Plastic Surgery in the Department of Plastic Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh.

References

- Frykberg RG, Lavery LA, Pham H, et al. Role of neuropathy and high foot pressures in diabetic foot ulceration. Diabetes Care. 1998; 21(10):1714-9.

- Abouaesha F, van Schie CH, Armstrong DG, et al. Plantar soft-tissue thickness predicts high peak pressure in the diabetic foot. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2004; 94(1):39-42.

- Abouaesha F, van Schie CH, Griffiths GD, et al. Plantar tissue thickness is related to peak plantar pressure in the high-risk diabetic foot. Diabetes Care. 2001; 24(7):1270-4.

- Young MJ, Cavanagh PR, Thomas G, et al. The effect of callus removal on dynamic plantar foot pressures in diabetic patients. Diabetic Med. 1992; 9(1):55.

- Boulton AJ, Franks CI, Betts RP, et al. Reduction of abnormal foot pressures in diabetic neuropathy using a new polymer insole material. Diabetes Care. 1984; 7(1):42-46.

- Davis BL, Kuznicki J, Praveen SS, et al. Lower-extremity amputations in patients with diabetes: pre- and post-surgical decisions related to successful rehabilitation. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2004; 20(Suppl 1:)S45-50.

- Chairman EL. Restoration of the plantar fat pad with autolipotransplantation. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1994; 33(4):373-9.

- Pu LLQ, Coleman SR, Cui X, Ferguson REH, Vasconez HC. Autologous fat grafts harvested and refined by the Coleman technique: a comparative study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010; 122(3):932-937.

- Rocchio TM. Augmentation of atrophic plantar soft tissue with acellular dermal allograft: a series review. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2008; 26(4):545-57.

- Van Schie CH., Whalley A, Armstrong DG, Vileikyte L, Boulton AJ. The effect of silicone injections in the diabetic foot on peak plantar pressure and plantar tissue thickness: a 2- year follow-up. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002; 83(7):919-923.

- Balkin SW. Injectable silicone and the foot: a 41-year clinical and histological history. Dermotol Surg. 2005; 31(11 Pt2):155-9.

- Gusenoff J, Mitchell R, Jeong K, et al. Autologous fat grafting for pedal fat pad atrophy: a pilot study. Presented at the International Federation for Adipose Therapeutics and Science, New Orleans, October 2015.

For further reading, see “Expert Insights On Therapies For Plantar Fat Pad Atrophy” at https://tinyurl.com/qapzb4x , “A Closer Look At The Plantar Fat Pad In People With Diabetes” in the January 2010 issue of Podiatry Today or “Are Acellular Dermal Matrices Effective For Grade 0 Ulcers And Fat Pad Augmentation?” in the November 2012 issue.