Acral Lentiginous Melanoma: What Sets It Apart?

With diagnostic issues ranging from variations in the clinical presentation to delayed detection of lesions on the sole of the foot, acral lentiginous melanoma can be a particularly challenging condition, which reportedly has a staggering misdiagnosis rate between 25 to 36 percent. Accordingly, this author discusses the etiology of the condition, reviews key diagnostic clues and advocates the benefits of dermoscopy for earlier diagnosis.

With diagnostic issues ranging from variations in the clinical presentation to delayed detection of lesions on the sole of the foot, acral lentiginous melanoma can be a particularly challenging condition, which reportedly has a staggering misdiagnosis rate between 25 to 36 percent. Accordingly, this author discusses the etiology of the condition, reviews key diagnostic clues and advocates the benefits of dermoscopy for earlier diagnosis.

All doctors have the challenge of detecting malignant melanoma early enough to help save lives. However, podiatrists frequently confront acral nevi with especially challenging appearances. Pigmented lesions of the sole have distinctive features that go beyond the classic A to E diagnostic criteria (asymmetry, border, color, diameter, evolving). In addition, plantar melanomas are characteristically late to get a diagnosis, have a poorer response to treatment and unfortunately, a significantly higher mortality rate in comparison to more proximal melanomas.

Although some perceive melanoma in general to be rare, the incidence of melanoma worldwide is rising dramatically and despite increased efforts at screening, mortality rates have not appreciably improved.1 In the United States, the incidence of melanoma has doubled in the last 10 years.2 It is currently the fifth leading cancer in men and the seventh in women.2

Is this an actual increase in incidence or is it due to more frequent skin biopsies? Have changes in histologic interpretation criteria led to increased diagnosis? Is the increasing incidence rate perhaps related to more intense screening?3 Actually, these explanations do not account for the increase in melanoma mortality rates. A study of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data from 1992 to 2004 found that the actual incidence of melanoma of all thicknesses and among all socioeconomic levels is an absolutely increasing burden from 4.7 to 7.7 cases per 100,000 older men and from 5.5 to 13.9 cases per 100,000 females.1,4,5 Improved biopsy criteria are helping physicians make an earlier diagnosis that lessens overall mortality but this does not signify a true increased incidence of melanoma.

The actual increase in melanoma incidence is most likely due to an overall increase in ultraviolet light exposure. Childhood sunburns that are intermittent and severe are strongly associated with an increased risk of melanoma while more incremental occupational exposure does not confer an increased risk.1 These findings support the hypothesis that melanoma risk is affected primarily by intermittent intense sun exposure, which seems to paralyze the normal immune surveillance and destruction of abnormal melanocytes.1 A survey of patients from an academic dermatology clinic found that exposure to indoor tanning beds was a significant risk factor for the development of melanoma and that this risk was even greater among women younger than 45 years.5

The actual increase in melanoma incidence is most likely due to an overall increase in ultraviolet light exposure. Childhood sunburns that are intermittent and severe are strongly associated with an increased risk of melanoma while more incremental occupational exposure does not confer an increased risk.1 These findings support the hypothesis that melanoma risk is affected primarily by intermittent intense sun exposure, which seems to paralyze the normal immune surveillance and destruction of abnormal melanocytes.1 A survey of patients from an academic dermatology clinic found that exposure to indoor tanning beds was a significant risk factor for the development of melanoma and that this risk was even greater among women younger than 45 years.5

The evidence is not all bad. New immunotherapy treatment is helping to decrease disease-specific mortality rates, especially in young patients who develop melanoma.6

But how does melanoma develop on feet that seldom see the light of day? Sunburn in adolescence damages lifelong immune surveillance and disturbs the normal apoptosis of neoplastic cells. Genetic susceptibility helps account for melanoma in shaded areas. As many as one in 10 cases of melanoma may be linked to inherited faulty genes.7 People who have had one melanoma and a parent with melanoma have a 30 times higher risk than the general population of developing another melanoma.7

Differentiating Among The Types Of Melanoma In The Foot

There are basically four types of melanomas arising in the foot: nodular, superficial spreading, subungual melanomas and the most common, acral lentiginous melanomas.8

Interestingly, acral lesions are not just on the foot. The acral areas include the palms, soles, volar surfaces of fingers and toes, and ungual regions. Palmoplantar skin is anatomically and histologically unique. The sole is characterized by a thick, compact cornified layer with prominent dermatoglyphics that consist of wide parallel ridges and narrow dermatoglyphic furrows or sulci that form loops, whorls and arches in highly individualized patterns.9

Interestingly, acral lesions are not just on the foot. The acral areas include the palms, soles, volar surfaces of fingers and toes, and ungual regions. Palmoplantar skin is anatomically and histologically unique. The sole is characterized by a thick, compact cornified layer with prominent dermatoglyphics that consist of wide parallel ridges and narrow dermatoglyphic furrows or sulci that form loops, whorls and arches in highly individualized patterns.9

The plantar epidermal basement membrane barrier is regularly perforated by many eccrine ducts. There are about 300 plantar eccrine ostia per square inch. These passages can help melanoma penetrate deeper and subsequently facilitate metastatic spread. While we know increased overall health benefits occur with 10,000 steps per day and the average person actually walks about 5,000 steps per day, the accumulated effect of thousands of impacts of direct and shear pressures can add a significant element of risk for melanoma initiation and spread.

Although 5 percent of all melanomas are located on the foot, pedal melanoma is relatively rare in Caucasians.6 Among East Asians and darkly pigmented people, acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common subtype of melanoma.7 Pedal melanoma has a poorer prognosis than melanoma in other body parts and patients are more likely to die of pedal melanoma than even proximal limb melanoma.8,10 Even though the foot receives less solar exposure, it turns out pedal melanoma is more likely to kill patients than more proximal thigh melanoma.10 Although the five-year survival rate for melanoma of the calf is 94 percent, the five-year survival rate for foot melanoma is only 77 percent.10 In addition, acral melanoma is associated with a significantly poorer prognosis than the other subtypes of melanomas. Researchers believe this may be due to the intrinsically aggressive behavior of pedal melanoma as well as delayed detection and diagnosis.11

Why Is Acral Melanoma More Lethal?

Why Is Acral Melanoma More Lethal?

Clinically, an acral lentiginous melanoma appears as a dark, brown to black, unevenly pigmented patch.12 Focal areas of tumor regression may manifest as gray-white discoloration. If a lesion becomes raised or becomes an ulceration, the likelihood of invasion is much higher. In addition, some tumors that invade along the perieccrine adventitial dermis may clinically appear flat though they have penetrated deeper to the subcutaneous adipose tissue.13

Why is acral melanoma more lethal? One reason for the prognostic difference may be the general omission of feet from general physical examinations. I remember seeing an 85-year-old gentleman with dementia who presented for foot care with a 3 cm nodular melanoma on the dorsum of his foot. He had a past medical history of a melanoma on his back and actually had an exam by his dermatologist that morning for his annual post-melanoma screening exam with his socks on.

Older age is another risk factor. Misdiagnosed cases occur predominantly in the sixth decade, reflecting the relative frequency of underlying vascular and neurological disorders in older patients. Patients themselves are also less likely to examine all the areas of their feet as they get older. With decreased flexibility and poorer vision that may accompany aging, it is naturally more difficult to examine one’s own feet.

Once the abnormality is noticeable, there is still a substantial rate of misdiagnosis. The incorrect clinical diagnosis rate of acral lentiginous melanoma is between 25 and 36 percent.14,15 In missed melanoma cases, original diagnoses have ranged from plantar warts to tinea nigra and talon noir.11,16,17 Unfortunately, we have all seen case reports of acral melanoma that masqueraded as a diabetic ulcer for years or a “wart” or “granuloma” that a physician removed but did not send out for definitive diagnosis.18,19

Once the abnormality is noticeable, there is still a substantial rate of misdiagnosis. The incorrect clinical diagnosis rate of acral lentiginous melanoma is between 25 and 36 percent.14,15 In missed melanoma cases, original diagnoses have ranged from plantar warts to tinea nigra and talon noir.11,16,17 Unfortunately, we have all seen case reports of acral melanoma that masqueraded as a diabetic ulcer for years or a “wart” or “granuloma” that a physician removed but did not send out for definitive diagnosis.18,19

Making matters even more challenging, acral lentiginous melanomas are usually pigmented but in 2 to 8 percent of cases, they are amelanotic.18 This may lead to the clinical misdiagnosis of these melanomas as not only warts but traumatized calluses or even chronic paronychia. This is especially a problem with subungual amelanotic melanoma. It is interesting to note that all types of physicians have initially misdiagnosed pedal melanoma as intractable diabetic skin ulcers.20 These reports help explain why melanoma is a perennial topic at podiatry continuing education seminars.

Facilitating Earlier Detection With Dermoscopy

So what is our best defense against missed diagnosis? In addition to increasing our clinical vigilance, improving our examination skills will help detect acral lentiginous melanoma earlier. We are all well trained to practice the A through E melanoma examination checklist, which research has proven to reduce melanoma deaths.21 However, the A through E checklist is not sensitive enough when it comes to evaluating plantar nevi.21

Dermoscopy increases the sensitivity of the clinical examination by 20 percent.18 Madankumar and colleagues, in a recent study of acral melanocytic lesions, concluded that plantar melanocytic lesions are quite common and carry an increased mortality.11 They also noted that dermoscopy of acral lesions is an important tool for the diagnosis and management of plantar pigmented lesions. There has been a rapidly growing acceptance of dermoscopy as an examination method. Educators are currently teaching it to an increasing number of podiatrists, primary care physicians and dermatologists. The American Society of Foot and Ankle Dermatology has lectures and workshops on dermoscopy.22

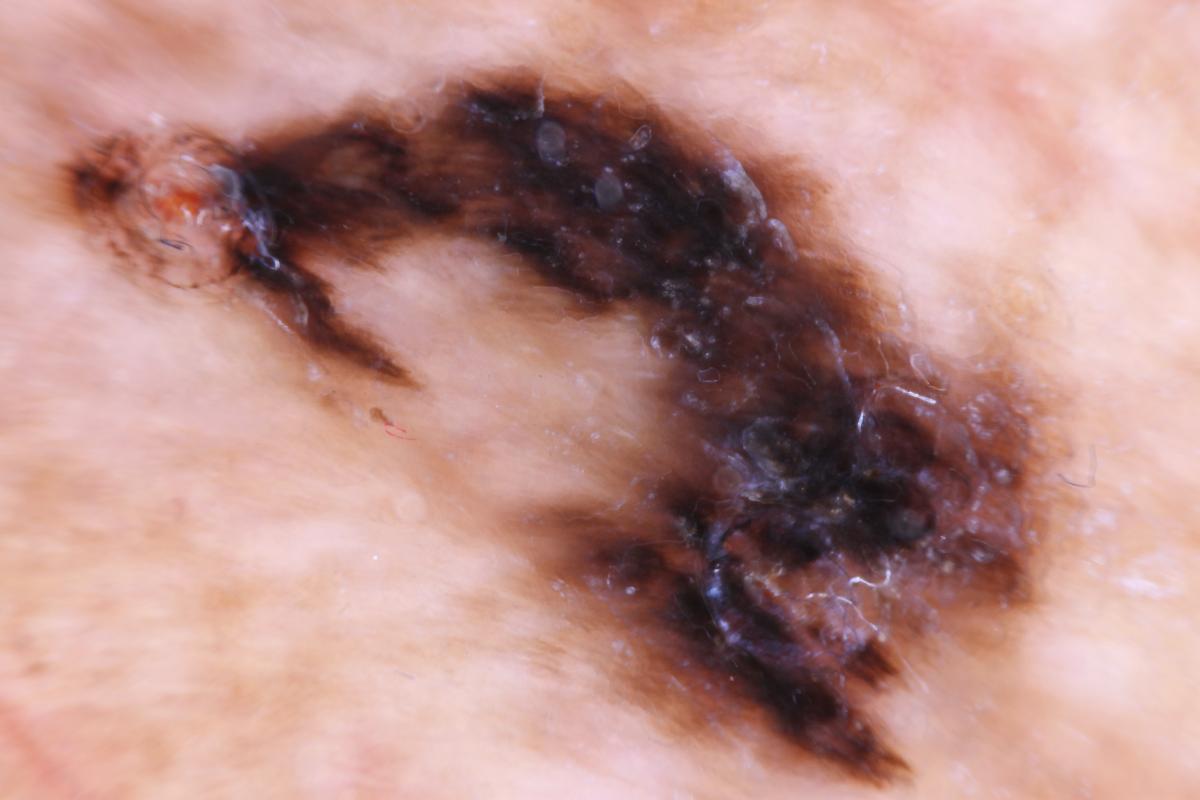

Dermoscopy is a non-invasive technique that facilitates accurate screening examination of the skin. Not only does the dermatoscope provide up to 10 times the magnification of the skin lesion but the use of polarized light allows visualization of the upper dermis, revealing characteristics of melanoma specific patterns not seen before clinically. Dermoscopy visualizes clinical features that correlate with known malignant and benign histopathology. Interestingly, the anatomical structure of acral volar skin results in several unique and distinctive dermoscopic patterns. Recognizing these patterns on the soles and palms increases the diagnostic acumen of the clinician by 20 percent, leading to more biopsies, not fewer.18

Dermoscopy is a non-invasive technique that facilitates accurate screening examination of the skin. Not only does the dermatoscope provide up to 10 times the magnification of the skin lesion but the use of polarized light allows visualization of the upper dermis, revealing characteristics of melanoma specific patterns not seen before clinically. Dermoscopy visualizes clinical features that correlate with known malignant and benign histopathology. Interestingly, the anatomical structure of acral volar skin results in several unique and distinctive dermoscopic patterns. Recognizing these patterns on the soles and palms increases the diagnostic acumen of the clinician by 20 percent, leading to more biopsies, not fewer.18

Plantar melanocytes are characteristically arranged in specific patterns. To explain these patterns, let us first imagine a freshly planted garden that has mounded parallel rows of wide ridges with long lines of equally spaced seedlings. These mounded rows are separated by narrower irrigation channels or furrows. Now think how the garden architecture resembles volar skin dermatoglyphics. The garden pattern with the mounded rows become the epidermal papillary ridges, studded with regularly spaced eccrine duct openings, just like the seedlings in the garden. These prominent papillary ridges are regularly separated by shallow narrower parallel epidermal furrows.

Most importantly, in normal plantar and palmar nevi, the pigment generally stays within the narrow parallel furrows between the wider epidermal ridges while melanoma typically violates this regular pattern when it spreads into adjacent ridges. Violation of the normal parallel furrow pattern is a very sensitive sign for early acral melanoma.

In their review of 712 acral melanocytic lesions, Saida and Miyzaki found the parallel ridge pattern and irregular diffuse pigmentation positively predicted melanoma over 93.7 percent of the time.23 Conversely, the authors found the parallel furrow pattern lesions were benign over 93.2 percent of the time.

Taking the dermoscopic interpretation a step further, there are three distinct benign pigment patterns that are characteristic findings in different areas of the foot. These areas tend to differ in the degree and direction of weightbearing forces. The weightbearing areas of the sole naturally include the heel, lateral plantar foot and the plantar toe pads, and typically exhibit a normal fibrillar pattern. The fibrillar pattern has parallel pigmented furrows and fine angulated cross-filaments. The most common benign pattern is the parallel furrow pattern, which is often present along the edge of the direct weightbearing zones.9 Finally, the crisscross lattice pattern is typically present in the arch area of the sole.

A Guide To Using The Three-Step Dermoscopic Algorithm For Melanocytic Lesions

Authors originally proposed a three-step algorithm for the diagnosis and management of melanocytic lesions of the soles and palms in 2007, and Saida and coworkers revised it in 2011.24-26 The first step of this algorithm is based upon the high sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values (86, 99 and 94 percent respectively) of the parallel ridge pattern for early acral melanoma.24 The sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values of the parallel furrow pattern/lattice-like pattern for benign melanocytic nevi are 67, 93 and 98 percent respectively.24

Step 1. Placing the dermatoscope against the skin, examine the lesion for the presence of the distinctive malignant parallel ridge pattern. If the parallel ridge pattern is visible in any part of the lesion, take a biopsy of the lesion regardless of the size. If the lesion does not show the parallel ridge pattern, it is safe to proceed to step 2.

Step 1. Placing the dermatoscope against the skin, examine the lesion for the presence of the distinctive malignant parallel ridge pattern. If the parallel ridge pattern is visible in any part of the lesion, take a biopsy of the lesion regardless of the size. If the lesion does not show the parallel ridge pattern, it is safe to proceed to step 2.

Step 2. Examine the lesion for the presence of one or more orderly benign dermoscopic patterns such as the typical parallel furrow pattern, the typical lattice-like pattern or regular fibrillar pattern. If the lesion shows one or a combination of two or three typical benign patterns, further dermoscopic follow-up is not needed. If the lesion shows equivocal dermoscopic features (such as the absence of any typical or regular patterns), proceed to step 3.

Step 3. Measure the maximum diameter of lesions that do not show typical benign patterns. Excise lesions larger than 7 mm or biopsy them for histopathologic evaluation.27 When it comes to lesions 7 mm or smaller, one should ensure clinical and dermoscopic monitoring at three- to six-month intervals.

The articles of Bristow and colleagues on the early identification of foot melanoma in the Journal of Foot and Ankle Research beautifully explain and illustrate acral nevi dermoscopy techniques.28-29 Additional dermoscopy patterns that describe vascular architecture have already been validated for the diagnosis of pigmented skin lesions in general and may be useful in the diagnosis of amelanotic acral melanoma. These include milky-red areas and dotted, hairpin and irregular vessels.30 Dermoscopic features of satellite lesions may appear as areas of homogenous, globular and structure-less blue-gray areas.31

Finally, it is important to emphasize that early and accurate diagnosis of thin lesions leads to life-saving treatment of melanoma. Dermoscopic examination of wounds with delayed healing can help detect the vascular and dermal changes that are characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma as well as amelanotic melanoma.

Understanding The Nature Of Melanocytes

Melanocytes are embryologically derived from neural crest as opposed to ectoderm. Melanocytes already have embryologically expressed DNA programming that enhances their pathogenicity, allowing metastatic spread around the body along and through blood vessels, lymphatic vessels and along nerves. During embryogenesis, the neural crest-derived melanocytes migrate into the epidermis and hair follicles to reside in the basal layer of the epidermis. These melanocytes, which are spaced at approximately every 10th cell along the basal layer, possess dendritic processes that transfer melanosomes to 20 neighboring keratinocytes and hair matrices. Nevi (both congenital and acquired) are composed of nevus cells, which are melanocytes that have lost their dendritic processes and typically proliferate clonally to form nests of cells. The more common acquired nevus begins as a flat lesion (junctional nevus) and over time progresses to an elevated lesion (compound nevus).13

Thankfully, most melanomas arise as superficial tumors that are confined to the epidermis, where they remain for several years. This stage is the horizontal or “radial” growth phase. During this stage, the melanoma is almost always curable by surgical excision alone. At some point, probably in response to the stepwise accumulation of genetic abnormalities, the melanoma transforms into an expansile nodule that extends beyond the biologic boundary of the basement membrane and invades the dermis.

Malignant melanoma in situ is a form of the radial growth phase melanoma in which the proliferation of malignant melanocytes is restricted to the epidermis. Of the four major subtypes of melanoma, an in situ form exists for superficial spreading, acral lentiginous and lentigo maligna melanomas, but not nodular melanomas, which are in the vertical growth phase from their initial development. In the superficial spreading variant of malignant melanoma in situ, the malignant melanocytes extend away from their normal position along the basal layer throughout the epidermis and even into the stratum corneum, a phenomenon termed “pagetoid spread.”

Acral lentiginous malignant melanomas in situ are characterized by uniformly atypical dendritic melanocytes that are aligned in a contiguous array along the dermal-epidermal junction. This feature helps to explain the pathologic parallel ridge pattern visible in acral melanoma. Invasive lesions are characterized by the presence of neoplastic single cells or nests in the dermis.13

What You Should Know About The Management Of Acral Melanoma

Our professional charge as physicians is to be vigilant for clinically suspicious lesions and triage them to biopsy, monitoring or patient reassurance. Whether we biopsy the lesion ourselves or arrange for biopsy by others, we are at a pivotal point of care to help reduce overall mortality.

If one chooses a total excisional biopsy, Stone and colleagues recommend a 1 to 2 mm rim of normal appearing skin along with a cuff of subdermal fat as the optimal technique.32 Once one finds melanoma by either the punch or total excisional technique, the authors recommend wider excision with surgical margins of 1 cm for tumors that are 2 mm thick or less and up to 5 cm for tumors that are over 2.1 mm in thickness. This obviously can lead to extensive tissue loss, which may require amputation.

If one chooses a total excisional biopsy, Stone and colleagues recommend a 1 to 2 mm rim of normal appearing skin along with a cuff of subdermal fat as the optimal technique.32 Once one finds melanoma by either the punch or total excisional technique, the authors recommend wider excision with surgical margins of 1 cm for tumors that are 2 mm thick or less and up to 5 cm for tumors that are over 2.1 mm in thickness. This obviously can lead to extensive tissue loss, which may require amputation.

In general, clinicians allow plantar melanoma excision sites to granulate in as opposed to performing primary closure. Once primary healing has taken place, the use of skin grafting and flaps can help restore weightbearing function. Mohs microsurgery can minimize tissue loss but has yet to be proven effective in reducing overall patient mortality.

Further patient evaluation by a melanoma specific oncology team is important to improve outcome. After a diagnosis, it is important to get a staging of the cancer so a melanoma management team can develop the most effective treatment plan.

The Melanoma Staging Database is based on clinical experiences in over 38,900 patients with melanoma and incorporates a tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system.30,33,34 It relies upon assessments of the primary tumor, regional lymph nodes and distant metastatic sites. The Breslow thickness primarily determines the “T” and one modifies this by the mitotic rate of the tumor. The 10-year survival rate decreases progressively from 96 percent with primary lesions < 0.5 mm thick to 54 percent with lesions 4.01 to 6 mm thick. The “N” or lymphatic node designation assesses regional lymph node spread and has a major negative impact on long-term survival.

The sentinel lymph node biopsy is recommended for tumors equal to or greater than 0.75 mm thick. The sentinel lymph node biopsy is also recommended for thinner tumors that are ulcerated, have lymphovascular invasion or a mitotic rate greater than or equal to 1 mitotic figure per square millimeter.33 One can use Technetium-99 through a handheld gamma probe for preoperative mapping and intraoperative identification in the operating room.35,36 If there is positive identification of a melanoma, authors recommend complete lymph node dissection. Adjuvant interferon alfa is then recommended in patients who have a life expectancy of greater than 10 years.

Current Insights On Immunotherapy

In the past, the prognosis of metastatic melanoma has been poor with a median survival of only 6.2 years and a one-year life expectancy of 25.5 percent. Currently, immunotherapy with monoclonal antibodies is turning the tide.37 Therapies that target T lymphocyte antigens can induce an antitumor immune response. Ipilimumab (Yervoy, Bristol-Myers Squibb) is the first approved immune checkpoint inhibitor and has shown durable objective responses.38 Twenty percent of patients are now surviving five years with ipilimumab.38 Complications include exacerbation of preexisting immune disorders.

Anti-programmed cell death (PD-1) monoclonal antibodies like nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol-Myers Squibb) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck Oncology) are other immune checkpoint inhibitors that have demonstrated more effective results than conventional drugs in clinical trials for a variety of advanced solid tumors including melanoma, non-small cell lung carcinoma and renal carcinoma.38 When it comes to plantar melanoma, the five-year disease-free survival rates are still significantly worse for patients with plantar melanomas in comparison with leg lesions of the same thickness.14,39 The five-year survival rate for plantar melanoma is now 82 percent for lesions up to 1.49 mm and 0 percent for lesions over 3.5 mm.40

In Conclusion

To help combat the increasing incidence of melanoma, we can improve patient survival with clinical vigilance, improved dermoscopy skills and more biopsies of atypical nevi. After detecting melanoma, referral to a melanoma specific management team will help to improve the melanoma mortality rate.

Dr. Bodman is an Associate Professor at the Kent State University College of Podiatric Medicine. He is board certified by the American Board of Podiatric Medicine.

References

- Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Atkins MB, Tsai H. Risk factors for the development of melanoma. UpToDate. Available at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/risk-factors-for-the-development-of-melanoma . Accessed January 4, 2016.

- Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9.

- Swerlick RA, Chen S. The melanoma epidemic. Is increased surveillance the solution or the problem? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(8):881.

- Linos E, Swetter SM, Cockburn MG, Colditz GA, Clarke CA. Increasing burden of melanoma in the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(7):1666

- Reed KB, Brewer JD, Lohse CM, Bringe KE, Pruitt CN, Gibson LE. Increasing incidence of melanoma among young adults: an epidemiological study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012; 87(4):328–334.

- Purdue MP, Freeman LE, Anderson WF, Tucker MA. Recent trends in incidence of cutaneous melanoma among US Caucasian young adults. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(12):2905–2908.

- Cancer Research UK. Available at https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/type/melanoma/about/melanoma-risks-and-causes . Accessed Jan. 16, 2016.

- Kato T, Suetake T, Tabata N, Takahashi K, Tagami H. Epidemiology and prognosis of plantar melanoma in 62 Japanese patients over a 28-year period. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(7):515.

- Elwan NM, Eltatawy RA, Elfar NN, Elsakka OM. Dermoscopic features of acral pigmented lesions in Egyptian patients: a descriptive study. Int J Derm. 2016;55(2):187-92.

- Bodman MA. Essential insights on dermoscopy of plantar pigmented lesions. Podiatry Today. 2015; 28(5):54-61.

- Madankumar R, Gumaste PV, Martires K, et al. Acral melanocytic lesions in the United States: Prevalence, awareness, and dermoscopic patterns in skin-of-color and non-Hispanic white patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 74(4):724-30.

- Coleman WP 3rd, Loria PR, Reed RJ, Krementz ET. Acral lentiginous melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116(7):773.

- Armstrong AW, Liu V, Mihm MC. Pathologic characteristics of melanoma. UpToDate. Available at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathologic-characteristics-of-melanoma . Accessed January 4, 2016.

- Koh HK, Geller AC, Lew RA. Melanoma. In Kramer BS, Gohagan JK, Prorok PC (Eds): Cancer Screening: Theory and Practice, Marcel Dekker, New York 1999, p. 379.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Available at https://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/webcontent/acspc-042151.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2014.

- Fortin PT, Freiberg AA, Rees R, et al. Malignant melanoma of the foot and ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995; 77(9):1396–403.

- Barnes B, Seigler H, Saxby T, Kocher M, Harrelson J. Melanoma of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994; 76(6):892-898.

- Bristow IR, Acland K. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the foot and ankle: a case series and review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Res. 2008;1(1):11.

- Rogers LC, Armstrong DG, Boulton AJ, Freemont AJ, Malik RA. Malignant melanoma misdiagnosed as a diabetic foot ulcer. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):444–5.

- Kaneko T, Korekawa A, Akasaka E, Nakano H, Sawamura D. Amelanotic acral lentiginous melanoma mimicking diabetic ulcer: An entity difficult to diagnose and treat. Eur J Dermatol. 2015; epub Dec. 14.

- American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force for the ABCDEs of Melanoma. Tsao H, Olazagasti JM, et al. Early detection of melanoma: reviewing the ABCDEs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015; 72(4):717-23.

- Vlahovic TC. Why dermoscopy is a valuable tool for podiatric dermatology. Podiatry Today DPM Blog. Available at: https://www.podiatrytoday.com/blogged/why-dermoscopy-valuable-tool-podiatric-dermatology#sthash.KbVBOG8r.dpuf . Published Sept. 18, 2015. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Saida T, Miyazaki A, Oguchi S, et al. Significance of dermoscopic patterns in detecting malignant melanoma on acral volar skin: results of a multicenter study in Japan. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(10):1233-8.

- Saida T, Koga H. Dermoscopic patterns of acral melanocytic nevi: their variations, changes, and significance. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(11):1423-6.

- Saida T, Koga H, Uhara H. Key points in dermoscopic differentiation between early acral melanoma and acral nevus. J Dermatol. 2011; 38(1):25-34.

- Koga H, Saida T. Revised 3-step dermoscopic algorithm for the management of acral melanocytic lesions. Arch Dermatol. 2011; 147(6):741-3.

- Saida T, Yoshida N, Ikegawa S, Ishihara K, Nakajima T. Clinical guidelines for the early detection of plantar malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(1):37-40.

- Bristow IR, de Berker DA, Acland KM, Turner RJ, Bowling J. Clinical guidelines for the recognition of melanoma of the foot and nail unit. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010;3:25.

- Bristow IR, Bowling J. Dermoscopy as a technique for the early identification of foot melanoma. J Foot Ankle Res. 2009; May 12;2:14.

- Buzaid AC, Gershenwald JE, Atkins MB, Ross ME. Tumor node metastasis (TNM) staging system and other prognostic factors in cutaneous melanoma. UpToDate. Available at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/tumor-node-metastasis-tnm-staging-system-and-other-prognostic-factors-in-cutaneous-melanoma . Accessed Feb. 8, 2016.

- Mansur AT, Demirci GT, Ozel O, Ozker E, Yıldız S. Acral melanoma with satellitosis, disguised as a longstanding diabetic ulcer: a great mimicry. Int Wound J. 2015; epub Sep 24.

- Stone M, Atkins MB, Weiser M, Tsao H, Berman RS, Ross ME. Initial surgical management of melanoma of the skin and unusual sites. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/initial-surgical-management-of-melanoma-of-the-skin-and-unusual-sites . Accessed Feb. 8, 2016.

- Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, Seventh Edition, Springer, New York, 2010, p. 325.

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6199.

- Krag DN, Meijer SJ, Weaver DL, Loggie BW, Harlow SP, Tanabe KK, Laughlin EH, Alex JC. Minimal-access surgery for staging of malignant melanoma. Arch Surg. 1995;130(6):654.

- Mudun A, Murray DR, Herda SC, et al. Early stage melanoma: lymphoscintigraphy, reproducibility of sentinel node detection, and effectiveness of the intraoperative gamma probe. Radiology. 1996;199(1):171.

- Valpione S, Campana LGI. Immunotherapy for advanced melanoma: future directions. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016; 8(2):199-209.

- Suzuki S, Ishida T, Yoshikawa K, Ueda R. Current status of immunotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016; 46(3):191-203.

- Seo J, Kim J, Nam KA, Zheng Z, Oh BH, Chung KY. Reconstruction of large wounds using a combination of negative pressure wound therapy and punch grafting after excision of acral lentiginous melanoma on the foot. J Dermatol. 2016;43(1):79-84.

- Dwyer PK, Mackie RM, Watt DC, Aitchison TC. Plantar malignant melanoma in a white Caucasian population. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128(2):115.

For further reading, see “Essential Insights On Dermoscopy Of Plantar Pigmented Lesions” in the May 2015 issue of Podiatry Today, “Recognizing Amelanotic Melanoma In The Lower Extremity” in the July 2010 issue, “What You Should Know About Malignant Melanoma” in the April 2008 issue or the DPM Blog “Why Dermoscopy Is A Valuable Tool For Podiatric Dermatology” by Tracey Vlahovic, DPM at https://tinyurl.com/qhhzelo .

For an enhanced reading experience, check out Podiatry Today on your iPad or Android tablet.