A Very Unusual Burn Complication: Bilateral Endogenous Bacterial Endophthalmitis

Abstract

Background. The authors report the rare, but potentially blinding, complication of bilateral endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis observed in a 35-year-old man during his admission to a regional burns center following a burn injury from an electronic cigarette device. This complication has been reported only twice in burn patients following extensive and life-threatening burn injuries. This patient underwent surgical debridement and split-thickness skin grafting of non-major burns as per standard of practice. In the postoperative period, the patient developed bilateral eye pain, redness, and photophobia, and was subsequently diagnosed with bilateral endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis secondary to a Staphylococcus aureus infection of the burn wound. After ophthalmology input and treatment with systemic and intravitreal antibiotics, he made a full recovery from both his burns and endophthalmitis.

Conclusions. This report describes a rare, sight-threatening complication that arose from an infected burn wound in an otherwise healthy patient. It highlights the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment to preserve vision and the need for burn surgeons to have a high level of awareness of this entity, even in the context of minor burns.

Introduction

In the United Kingdom, there is an increasing trend in burns caused by electronic cigarettes since their introduction in recent years.1,2 Fires and explosions linked to such devices are thought to be caused by malfunctioning lithium-ion batteries or faulty devices,3 and many users keep them in their pockets in close proximity to skin areas of the thighs, legs, and buttocks. As a result, these burns can be significant and often require inpatient care and surgical treatment at a specialist burn center. Infection of acute burn wounds is a common complication, and in larger burns this can often lead to sepsis and require admission to intensive care. Such infections are a significant cause of mortality in burn patients, with the breached area of skin being a key entrance for infection.4

Although burn wounds are initially sterile following thermal injury, they can become colonized with gram-positive, gram-negative, and fungal organisms, leading to systemic bacteremia and sepsis in some cases.5 This bacterial colonization often occurs in the form of a biofilm, with Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa being the most common cause of burn wound infections.4 The risk factors for burn wound infections include male sex, older age, diabetes, and immunocompromised state, and patients with larger full-thickness burns and burns over the lower extremity are also at increased risk.5 The prompt recognition and treatment of these infections with appropriate antibiotics, guided by microbiology culture and sensitivity, is an important aspect of burn management.

Endophthalmitis refers to intraocular inflammation secondary to infection, usually bacterial or fungal, within intraocular spaces. It is potentially devastating and carries a poor visual prognosis in most patients.6 It is classified as exogenous or endogenous depending on the route of infection to the eye. Exogenous endophthalmitis occurs when microorganisms enter the eye from a breach of external ocular barriers (eg, following intraocular surgery, intraocular injections, or penetrating trauma). Contrastingly, endogenous endophthalmitis occurs when microorganisms enter the eye by crossing the blood-ocular barrier via hematogenous spread from a distant source of infection.7 In these cases, there is no direct trauma to the eye, and as such, eye protection would not protect against this condition. Endogenous endophthalmitis is less common than the exogenous form and is responsible for about 2% to 8% of endophthalmitis cases.7 Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis (EBE) in burns patients is rare. There are currently only 2 case reports, and these have described patients with significant burns of more than 40% total body surface area (TBSA).8,9 It is important to recognize this significant complication promptly so that the patient can receive specialist input, investigations, and early treatment to prevent visual loss.

Methods

A previously healthy 35-year-old man presented to the emergency department after sustaining a flame burn to his left thigh and leg when a lithium-ion battery–powered electronic cigarette in his pocket spontaneously caught fire. The burn was assessed as 5% TBSA, with areas of deep dermal to the left anterior thigh, mid dermal to the left lateral thigh, and deep dermal to the left calf. The patient was admitted to a regional burn center for management. On admission, routine microbiology swabs from the burn wounds showed no pathogenic organisms, and results of admission blood tests were unremarkable. Four days following the presentation, the patient underwent uncomplicated surgical debridement, dermabrasion, and reconstruction of the burn with a split-thickness skin graft.

The morning following surgery, the patient developed a fever; his temperature was 102.4°F (39.1°C). He had no other new symptoms. Results of laboratory studies showed a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 127 mg/dL and mild neutrophilic leukocytosis (leukocytes, 12.89 × 109, neutrophils, 10.45 × 109); however, no clear source of infection was evident clinically, and blood cultures taken at this time showed no growth.

The following night, the patient had sustained pyrexia of >102.2°F (>39°C) while all other clinical observations remained normal. The next morning, he awoke with bilateral eye redness, pain, and photophobia. Urgent ophthalmology assessment demonstrated well-preserved visual acuities (6/6 right and left) and bilateral nongranulomatous anterior uveitis, worse in the left eye, with no hypopyon and no posterior synechiae. Limited posterior segment assessment at the bedside showed no suggestion of vitritis or vitreous haze in either eye, and the ocular fundi were normal bilaterally. He was initially treated with prednisolone and cyclopentolate eye drops.

The patient remained persistently febrile (>48 hours in total) with eye pain, redness, and photophobia associated with generalized myalgia but no hemodynamic instability. Subsequent laboratory results showed a rising CRP (302 mg/dL) and neutrophilic leukocytosis (leukocytes, 16.35 × 109; neutrophils, 14.21 × 109) on postoperative day 2. A systematic clinical examination, plain radiograph of the chest, and urine screen showed no other source of infection, and serial COVID-19 RNA swabs and results of a comprehensive autoantibody panel were all negative. Repeated blood cultures continued to show no growth, but microbiology swabs from the burn wound at this time isolated a fully sensitive S aureus.

Per routine burn center protocol, the operating surgeon checked the graft 48 hours after surgery to confirm graft take and graft health. At this check, the wound appeared healthy with 100% graft take, and the donor site was clean and healing with no clinical indication of active infection.

Results

Bedside ophthalmology assessment on postoperative day 3 showed stable vision and stable uveitis activity. However, given the clinical context of this uveitis, the pyrexia, and the blood picture, there was strong clinical suspicion of a low-grade EBE from S aureus infection at the site of the burn wound despite the lack of an obvious skin infection clinically. Following consultation with microbiology, high-dose intravenous antibiotics (meropenem and linezolid) were started promptly for treatment of EBE. On postoperative day 4, the patient’s fever had resolved, and bedside ophthalmology assessment showed stable findings.

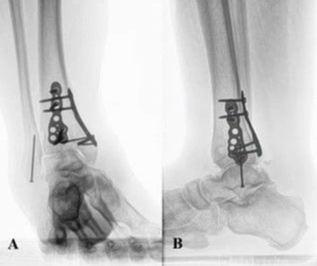

On postoperative day 5, a more detailed outpatient ophthalmology assessment showed stable visual acuities but a worsening of uveitis activity and bilateral vitritis with left vitreous haze (Figure). Fundoscopy remained normal. Left intravitreal antibiotics (vancomycin and ceftazidime) were administered uneventfully.

Intravenous antibiotics were continued for 8 days, followed by oral moxifloxacin for 7 days. CRP and neutrophil count were within normal parameters by postoperative day 10. Serial ophthalmology assessments showed steady improvement of his uveitis activity, and eye examination at 1 month after surgery was completely normal off all treatments. His burn and split-thickness skin graft healed well following surgery, and the patient returned to work with no long-term complications.

Discussion

This is the first case report of EBE developing following a minor burn injury; 2 previous cases document this developing in major burns greater than 40% TBSA. This case should highlight to burn surgeons the potential for patients to develop this sight-threatening condition even in the context of non-major burns. The first previously reported case, in 1995, occurred in a 35-year-old male patient following an explosion burn over 75% TBSA.9 This patient had a complex admission and developed pseudomonas septicemia after 20 days in hospital. After 9 weeks, his visual symptoms started in his right eye only, and a diagnosis of endophthalmitis was made. In this case, the patient’s eye could not be salvaged, and evisceration was performed. The causative microorganism was identified as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The second case, reported in 2017, was observed in a 12-year-old girl admitted with full-thickness burns over 46% TBSA.8 This patient was similarly treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics for severe sepsis during an extended hospitalization. Visual symptoms began on day 23 of her admission in her right eye only. Unilateral endogenous endophthalmitis was diagnosed with a vitreous biopsy revealing the presence of Candida albicans.8

In contrast to these earlier cases, the authors have reported a unique case of bilateral EBE in a burn patient with a mixed-depth burn over only 5% TBSA. Visual and systemic symptoms occurred 6 days into the admission, suspected to be secondary to an infected burn wound where S aureus was isolated on wound swab. Unlike the 2 previous reports, the current patient developed bilateral endophthalmitis, and at a relatively early time point during the admission. Furthermore, his burn injury was far less extensive that the previously reported cases, suggesting that this ocular complication can occur following burn wounds of varying severities, including minor burns. Before his visual symptoms developed, the patient was also hemodynamically stable with no evidence of septicemia (in contrast to the significant systemic responses reported in the 2 previous cases8,9), making this a particularly unsuspected and unique diagnosis.

EBE is a rare eye infection, representing <10% of all cases of endophthalmitis.9 Two-thirds of patients with the condition have host risk factors for infection, such as diabetes, valvular heart disease, pulmonary disease, renal failure, hemodialysis, malignancy, liver cirrhosis, splenectomy, indwelling catheters, and immunosuppressed states.6,10 In EBE, microorganisms are spread hematogenously from a source distant to the eye, in contrast to exogenous endophthalmitis where the infection enters directly through an external wound.7 Both are ophthalmological emergencies and often pose a diagnostic challenge since the presentation can be extremely heterogenous.

Patients with EBE usually report symptoms of blurred vision, floaters, eye redness, eye pain, and photophobia. Involvement may be bilateral in 20% of patients, with Neisseria meningitidis, Escherichia coli infection, and Klebsiella infection more likely to cause bilateral disease. Eye findings and their evolution can vary markedly. Fulminating infection may present with rapid visual loss, hypopyon uveitis, and dense vitritis obscuring any fundus view. In such cases, progression to orbital cellulitis may follow with proptosis and restriction of eye movements. Low-grade or indolent presentations may cause relatively mild anterior uveitis and vitritis with fundus lesions, such as Roth spots (white-centered retinal hemorrhages), retinal vasculitis, or subretinal abscesses.

Following ophthalmological suspicion of EBE, a thorough medical assessment should follow, with particular attention to risk factors and likely sources of systemic infection. Microbiological confirmation of infection is key to confirming diagnosis and treatment planning. Blood cultures and cultures from any possible sources of infection should be taken (eg, skin, urine, sputum). Where the responsible microorganism is not already identified, intraocular sampling is required by aqueous paracentesis or vitreous biopsy with specimens sent for Gram stain and cultures for aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal organisms.11 This analysis can be supplemented by DNA or RNA sequencing microanalysis and polymerase chain reaction to increase diagnostic yield, even with small tissue samples.11 In the current patient, no intraocular samples were taken because the diagnosis of EBE was reasonably secure on clinical grounds with supporting laboratory evidence of S aureus infection, and the risks of intraocular sampling (such as retinal detachment) were not felt to be worthwhile given his excellent visual acuities. As no microorganisms were isolated from intraocular fluids, the diagnosis would more correctly be termed “presumed” EBE.

Once clinically suspected and following appropriate microbiological sampling, EBE requires prompt and high-dose systemic antibiotic treatment; at first, a broad-spectrum antibiotic should be initiated if the causative agent is unknown, then tailored to the specific causative agent. The role of intravitreal antibiotics and vitrectomy surgery is less clear. It seems appropriate to give intravitreal antibiotic at the time of vitreous biopsy if that is performed, or to patients who continue to deteriorate despite medical treatment. However, a subanalysis of data from systematic reviews of EBE showed no correlation between intravitreal antibiotic use and better visual outcomes.6,10 Pars plana vitrectomy to clear the vitreous opacities and debulk infective and inflammatory mediators has been advocated if visual loss is profound from vitreous opacification, but whether early vitrectomy is beneficial is more doubtful.12 Finally, evisceration or enucleation are considered for patients who are irreversibly blind and in intractable pain. The visual outcome of EBE is poor, with 32% to 41% of patients achieving counting fingers vision or better; 26% to 57% losing their vision, and 14% to 29% requiring evisceration or enucleation.6,10,12 EBE also has a significant mortality rate of 5% from the consequences of sepsis. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment may improve these outcomes and reduce risk of second eye involvement.

Conclusions

This report presents a unique case of bilateral EBE in a young, previously healthy patient secondary to an infected burn wound over 5% TBSA. In this instance, prompt recognition and multidisciplinary management allowed appropriate treatment and led to an excellent outcome from both a burn care and ophthalmological perspective. This report highlights to burn surgeons the potential for patients to develop this sight-threatening condition, even in the context of minor burns.

Learning Points

- There is a rising trend in burns linked to electronic cigarette devices.

- Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis (EBE) is a rare but potentially sight-threatening complication in burn patients with wound infections.

- Although poor visual outcomes are common in EBE, early diagnosis and appropriate antimicrobial treatment may prevent visual loss.

- Surgical teams should be aware that eye symptoms, such as new onset of floaters or haziness of vision, eye redness, pain, or photophobia occurring in the context of known or possible systemic infection may indicate EBE, and prompt referral to ophthalmology is warranted.

- Following significant burn injuries, loss of portions of the skin barrier places patients at risk of colonization and development of multiresistant organisms.

Acknowledgments

Affiliations: 1The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; 2Translational and Clinical Research Institute, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; 3Department of Ophthalmology, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; 4Northern Regional Burn Centre, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

Correspondence: Corey D Chan, MBBS; corey.chan@newcastle.ac.uk

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial conflicts of interest.

References

1. Seitz CM, Kabir Z. Burn injuries caused by e-cigarette explosions: A systematic review of published cases. Tob Prev Cessat. 2018;4:32. doi:10.18332/tpc/94664

2. Arnaout A, Khashaba H, Dobbs T, et al. The Southwest UK Burns Network (SWUK) experience of electronic cigarette explosions and review of literature. Burns. Jun 2017;43(4):e1-e6. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2017.01.008

3. London Fire Commissioner. Vaping and e-cigarettes. London Fire Commissioner. 2022. Accessed January 6, 2023. https://www.london-fire.gov.uk/safety/the-home/smoking/vaping-and-e-cigarettes/

4. Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, Winston B, Lindsay R. Burn wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. Apr 2006;19(2):403-434. doi:10.1128/cmr.19.2.403-434.2006

5. Ladhani HA, Yowler CJ, Claridge JA. Burn Wound Colonization, Infection, and Sepsis. Surg Infect (Larchmt). Feb 2021;22(1):44-48. doi:10.1089/sur.2020.346

6. Greenwald MJ, Wohl LG, Sell CH. Metastatic bacterial endophthalmitis: a contemporary reappraisal. Surv Ophthalmol. Sep-Oct 1986;31(2):81-101. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(86)90076-7

7. Sadiq MA, Hassan M, Agarwal A, et al. Endogenous endophthalmitis: diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. Dec 2015;5(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12348-015-0063-y

8. Hosseini SM, Ahmadabadi A, Tavousi SH, Rezaiyan MK. Endogenous endophthalmitis after severe burn: a case report. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. Apr-Jun 2017;12(2):228-231. doi:10.4103/jovr.jovr_144_15

9. Jain ML, Garg AK. Metastatic endophthalmitis in a patient with major burns: a rare complication. Burns. Feb 1995;21(1):72-73. doi:10.1016/0305-4179(95)90788-2

10. Wong JS, Chan TK, Lee HM, Chee SP. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: an east Asian experience and a reappraisal of a severe ocular affliction. Ophthalmology. Aug 2000;107(8):1483-1491. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00216-5

11. Yanoff M, Duker J. Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

12. Jackson TL, Eykyn SJ, Graham EM, Stanford MR. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17-year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol. Jul-Aug 2003;48(4):403-423. doi:10.1016/s0039-6257(03)00054-7