Prophylactic Muscle Free Flap for Total Ankle Arthroplasty With Vascular Risk Factors

© 2023 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Total ankle arthroplasty (TAA) is a treatment for ankle arthritis that preserves the joint’s mobility. Conditions causing poor peripheral blood flow are contraindications for TAA. A 63-year-old man with posttraumatic ankle osteoarthritis who was considered high-risk for TAA due to obesity, history of trauma, tobacco usage, chronic venous stasis, lymphedema, and hypertension subsequently underwent TAA followed by a prophylactic muscle free flap to improve peripheral blood flow and soft tissue integrity. He recovered with no pain and excellent ankle mobility. This case highlights the potential usage of prophylactic muscle free flaps to mitigate vascular risk factors in high-risk patients undergoing TAA.

Introduction

Ankle arthrodesis (AA) and total ankle arthroplasty (TAA) address severe ankle arthritis, which can develop as a result of injury or due to aging.1 Although AA is a more common procedure, it has been shown to limit the range of motion in the hindfoot significantly.TAA involves complete removal and replacement of the ankle joint, providing greater mobility than that offered by AA, which fuses the joint.

The foot and ankle generally have reduced or limited vascular supply compared with the proximal extremity structures.2 Proper recovery after ankle surgery depends on adequate revascularization of the area, which may be complicated if peripheral circulation is compromised.2 As the dorsal ankle is solely supplied by the anterior tibial artery, poor vascularity is believed to be responsible for the risk of significant complications after TAA.2

Patient selection in TAA is critical, as specific risk factors are considered relative contraindications to foot and ankle surgery.3 These risk factors include, but are not limited to, smoking tobacco, hypertension, obesity, peripheral vascular disease, and diabetes.3 Additionally, a history of previous trauma or surgery to the distal lower extremity can compromise soft tissues and increase the risk of postsurgical complications after TAA.3

Reconstructive surgery using muscle free flaps has been well established in the literature to improve soft tissue quality and increase tissue perfusion.4 Additionally, muscle flaps have been shown to reduce dead space and improve lymphatic flow.5 The latissimus dorsi muscle free flap is a popular option for coverage of the dorsal compartment of the ankle due to its relative length and reliable blood vessels.6

We postulate that using a prophylactic, perioperative latissimus dorsi muscle free flap 2 to 3 days after TAA can improve outcomes and address soft tissue deficiencies in high-risk patients. Additionally, for those with poor peripheral vasculature due to comorbidities, such as obesity, lymphedema, and tobacco usage, a muscle flap may improve peripheral perfusion of the lower extremity. Previous literature has demonstrated a benefit to perioperative muscle flaps in knee arthroplasty.7 However, this benefit has yet to be established in ankle replacement surgery.

Methods

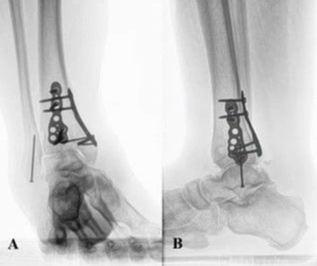

A 63-year-old man with right posttraumatic osteoarthritis was initially seen for constant ankle pain and paresthesia (Figure 1). The patient previously had a pilon fracture following a high-speed automobile accident. The fracture was repaired and fully healed with a posterior plate, medial plate, and screw fixation in the fibula (Figure 2). The patient adamantly declined undergoing AA because he wanted to maintain ankle mobility. Patient risk factors for poor peripheral circulation included a 10-pack-year smoking history, a body mass index of 37 kg/m2, and a medical history significant for chronic venous stasis, lymphedema, deep vein thrombosis, and hypertension. The listed risk factors caused him to be a poor surgical candidate, and TAA was relatively contraindicated. Additionally, on initial physical examination, he had visibly poor ankle integument, ankle hemosiderin deposits, and mild to moderate venous congestion.

To accommodate the patient’s desire to maintain ankle mobility, TAA after pilon hardware removal was proposed with a full discussion regarding the patient’s risks of lower extremity amputation due to possible sequelae based on his medical history. Due to poor anterior ankle skin integument and his risk profile, a reconstructive muscle free flap was recommended for proper incisional and improved soft tissue integrity. The patient was informed of all alternative treatment options, including conservative care and a second opinion, but he declined the second opinion and wished to proceed with the surgery. This patient also agreed to the publication of his case details and images.

The procedures performed included right TAA, posterior tibiotalar joint capsulotomy, talonavicular joint capsulotomy, Achilles tendon lengthening, the intertarsal synovectomy of the midtarsal joint, and tibia reinforcement (Figure 3). The latissimus dorsi muscle was isolated and anastomosed to the posterior tibial artery during the subsequent plastic surgery procedure.

Results

At 6 months after surgery, the patient reported to have been compliant with his non–weight-bearing status but still smoked cigarettes. He continued to have lymphedema with mild drainage around the flap but no signs of infection. The patient had no ankle pain or discomfort with range of motion. At this point, the patient was cleared to walk as tolerated.

Eight months after surgery (Figure 4), the patient attended physical therapy twice weekly for 5 weeks. He reported no pain, no wound drainage, and lessening lymphedema. On examination, his lower extremity reflexes, sensation, and strength were symmetrical and intact. There was no pain with range of motion and no point tenderness, and the range of motion was excellent at 15 degrees for dorsiflexion and 25 to 30 degrees for plantar flexion. The patient ambulated without pain or discomfort but had a slightly antalgic gait secondary to immobility for an extended period.

Discussion

Prophylactic reconstructive surgery can be utilized in total ankle arthroplasty to prevent such postoperative complications as wound persistence or infection by providing a reliable blood supply.4-6 TAA is associated with a high risk of complications, and historic contraindications, such as smoking, obesity, and hypertension, can compromise a patient’s peripheral blood flow.3 Previous studies assessing outcomes of relatively high-risk patients who underwent TAA without a muscle free flap autograft revealed increased risk of poor wound healing, infection rates, revision surgery, and decreased implant survivorship.8-10

This case report suggests that using a muscle free flap may improve outcomes, especially among high-risk patients with contraindications to TAA. The previously described patient had a history of ankle trauma, surgery, and substantial risk factors, including tobacco use, obesity, chronic venous stasis, lymphedema, deep vein thrombosis, and hypertension. The patient responded excellently to TAA despite multiple risk factors, which we believe are due to the prophylactic free muscle flap. A prophylactic latissimus dorsi free muscle flap improved the ankle’s blood supply and soft tissue integrity following TAA. As demonstrated by this case report, there is a need for further research on this topic with a larger cohort of study participants.

Prophylactic free muscle flaps have been described in the literature as a method of reducing dead space and significantly reducing complications in high-risk patients for femoral vascular surgery.11 They have been reported as safe, effective, and recommended for patients undergoing groin surgery with multiple comorbidities.11 This case report emphasizes similar considerations for locations more distal and with poorer vascularity, such as the ankle.

Conclusions

This case highlights the potential use of prophylactic reconstructive surgery to mitigate the risk of total ankle arthroplasty in patients with vascular contraindications. The case also highlights the importance of proper blood supply when operating on patients with vascular risk factors and in regions with poor peripheral blood flow.

Acknowledgments

Affiliations: 1Anne Burnett Marion School of Medicine at Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, Texas; 2Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; 3Precision Orthopedics & Sports Medicine, Fort Worth, Texas; 4MP Plastic Surgery, Fort Worth, Texas

Correspondence: Sofia E. Olsson, BS; sofia.olsson@tcu.edu

Funding: This research was not funded and was not performed as part of employment of the authors.

Ethics: The patient agreed to the publication of his case details and images.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial conflicts of interest.

References

1. Morash J, Walton DM, Glazebrook M. Ankle arthrodesis versus total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Clin. 2017;22(2):251-266. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2017.01.013

2. Attinger CE, Evans KK, Bulan E, Blume P, Cooper P. Angiosomes of the foot and ankle and clinical implications for limb salvage: reconstruction, incisions, and revascularization. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7 Suppl):261s-293s. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000222582.84385.54

3. van der Plaat LW, Haverkamp D. Patient selection for total ankle arthroplasty. Orthop Res Rev. 2017;9:63-73. doi:10.2147/ORR.S115411

4. Markovich GD, Dorr LD, Klein NE, McPherson EJ, Vince KG. Muscle flaps in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995(321):122-130.

5. Sedbon T, Azuelos A, Bosc R, D’Andrea F, Pensato R, Maruccia M, et al. Spontaneous lymph flow restoration in free flaps: a pilot study. J Clin Med. 2022;12(1). doi:10.3390/jcm12010229

6. Kang MJ, Chung CH, Chang YJ, Kim KH. Reconstruction of the lower extremity using free flaps. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40(5):575-583. doi:10.5999/aps.2013.40.5.575

7. Moog P, Tinwald I, Aitzetmueller M, et al. The usage of pedicled or free muscle flaps represents a beneficial approach for periprosthetic infection after knee arthroplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;85(5):539-545. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000002293

8. Lampley A, Gross CE, Green CL, et al. Association of cigarette use and complication rates and outcomes following total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Internat. 2016;37(10):1052-1059. doi:10.1177/1071100716655435

9. Schipper ON, Denduluri SK, Zhou Y, Haddad SL. Effect of obesity on total ankle arthroplasty outcomes. Foot Ankle Internat. 2016;37(1):1-7. doi:10.1177/1071100715604392

10. Sansosti LE, Van JC, Meyr AJ. Effect of obesity on total ankle arthroplasty: a systematic review of postoperative complications requiring surgical revision. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2018;57(2):353-356. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2017.10.034

11. Fischer JP, Nelson JA, Mirzabeigi MN, et al. Prophylactic muscle flaps in vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(4):1081-1086. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2011.10.110