The Double Donut: A Safe and Simple Option for Immediate Nipple Areolar Complex Reconstruction in Skin-Sparing Mastectomy Patients With Contraindications to Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy

© 2023 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Restoration of the nipple areolar complex (NAC) has been shown to improve quality of life (QoL) in post-mastectomy patients. Despite expansion of nipple-sparing mastectomy inclusion criteria, many patients remain ineligible and are relegated to bilateral skin-sparing mastectomy. In this study, we evaluated immediate NAC reconstruction with the double donut areolar graft and split nipple composite graft reconstruction (DDSNS).

Methods. A single-center prospective study was performed for patients undergoing immediate post-mastectomy reconstruction with the DDSNS technique. Demographics and post-reconstruction endpoints were collected, focusing on aesthetic and functional outcomes.

Results. A total of 31 patients and 62 breasts underwent immediate reconstruction with the DDSNS technique. Four of 62 (6.4%) nipple composite grafts and 1 of 62 (1.6%) areolar grafts experienced partial graft loss. All incidents of initial loss healed to a satisfactory result. All patients were able to proceed with adjuvant therapy, if indicated, without delay.

Conclusions. The DDSNS technique can be successfully applied to achieve cosmetically satisfactory results in the post-mastectomy patient. This technique has shown reliable outcomes with respect to graft success and patient satisfaction with their NAC reconstruction.

Introduction

The modern landscape of post-mastectomy reconstruction has prompted revisitation of the concept of nipple and areolar sharing to find a simple, reliable, and safe method to perform immediate nipple areola complex (NAC) reconstruction. Free transplantation of the nipples and areola as a method for immediate NAC reconstruction was first published by Adams in 19441. Millard went on to describe nipple and areola reconstruction by split-skin graft from the uninvolved side in 19722. Multiple configurations of nipple and areolar sharing have since been published, but no singular method has gained widespread popularity. Common problems of asymmetry, graft failure, and suboptimal aesthetic results have likely contributed to sparse utilization of free NAC grafting. With recent advancements in radiotherapy, patients with breast cancer (BC) are now more likely to receive adjuvant radiation therapy that increases the operative risks of delayed NAC reconstruction.3 This report presents a method of using free split nipple and areolar grafts in a double donut configuration as an option for the immediate reconstruction of the post-skin-sparing mastectomy patient. Metrics of oncologic safety and aesthetic appearance are of the utmost importance, as these NAC grafts are harvested from the non-cancerous breast.

Methods and Materials

A prospectively maintained database of patients undergoing immediate bilateral breast reconstruction using a subpectoral expander-to-implant method was reviewed. Patients included in this paper underwent immediate bilateral nipple and areolar reconstruction with free split nipple and areolar grafts in a double donut configuration. This study is a single-institution and single-surgeon experience of 31 patients and 62 breasts between October 2021 and May 2022. All reconstructions were performed by the senior author. Patients were offered this reconstruction option based on the following criteria:

1. All patients must have unilateral breast cancer and either need or desire bilateral mastectomy.

2. All patients must not be candidates for bilateral nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM).

3. All patients referred by the ablative surgeon have plans for bilateral skin-sparing mastectomy, based on having at least 1 of the following:

a. Grade 3 or 4 ptosis.

b. Planned tumor resection abutting or involving the NAC.

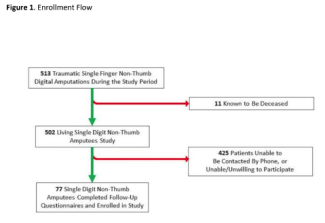

Preoperatively, the patient’s donor side nipple and areola were marked to demarcate the nipple from the areola. Two circular sites from the remaining areola were then marked as shown in Figure 1. At the time of the scheduled mastectomy, the reconstructive team scored the marks of the donor NAC and harvested the nipple and areola at the depth of a full-thickness graft. This was then placed in a saline cup while the ablative team proceeded with bilateral skin-sparing mastectomies. Meanwhile, the areolar portion of the NAC was aggressively thinned to the thickness of a split-thickness graft to optimize graft take. The nipple itself was left thicker as a composite graft and was then bisected, creating 2 equal nipple grafts. On each breast mound, the point of maximal projection was then roundly deepithelialized in preparation for the split nipple and areolar grafts. The nipple composite grafts were first secured using 5-0 chromic sutures in the center of the deepithelialized circle. The areolar grafts were then inset with a central cut to accommodate the protruding nipple composite graft. This gives an appearance that closely mimics a native NAC. The thinness of the areolar graft maximized the areolar graft take. Bolster dressings of xeroform, Adaptic, sponge, and tie-over sutures were secured over the grafts and remained in place for 4 weeks.

Results

A total of 31 patients and 62 breasts underwent immediate implant reconstruction with the double donut split nipple sharing (DDSNS) technique. Four of 62 (6.4%) nipple composite grafts partially failed and 1 of 62 (1.6%) areolar grafts experienced partial graft loss. All areas of initial graft loss spontaneously epithelialized without the need for revision. All patients were able to proceed with adjuvant therapy, if indicated, without delay. All patients reported satisfaction with their results. The mean time from expander to implant was 117 days with a standard deviation of 40.5 days.

Discussion

Post-mastectomy reconstruction remains one of the most common procedures of the reconstructive plastic surgeon. NSMs with reconstruction have been shown to improve patient satisfaction with their reconstruction.4 NSM has become the first option in the reconstructive pathway at many referral centers, but they are often not available at smaller or more remote hospitals.5 Women with significant ptosis or macromastia are often not candidates for nipple preservation with NSM.6 Historical contraindications to NSM such as ptosis and macromastia are being slowly eroded by newer concepts such as pre-mastectomy mastopexy and inframammary fold flaps.7 The pendulum is swinging in the direction of nipple preservation, but along with this momentum comes the recognition of complications due to the overextension of one’s faith in what are ultimately random pattern flaps. Though the trend is toward nipple preservation, not all patients are safe candidates for this technique and may be better served with NAC reconstruction. Patients who are not candidates for nipple preservation are then faced with options of immediate NAC reconstruction, delayed NAC reconstruction, or no NAC reconstruction.

The qualities of an ideal nipple reconstruction should include the subsequent items: safety, aesthetics, time, and sensation. First and foremost, it should not bear a significant risk of impacting the patient from an oncologic standpoint. This includes risks of transferring tumor-involved tissue as well as risks of wound complications that could delay adjuvant therapy. The second objective includes achieving durable and aesthetically pleasing results with special attention to projection, retention of pigment, and the ease of achieving symmetry. The third factor lies in the timely fashion or immediacy of the reconstruction, obviating the risks associated with NAC reconstruction following adjuvant radiation therapy. These risks include higher rates of infection, flap failures, implant exposure, loss of the reconstruction, and capsular contracture.3 An immediate reconstruction would also provide the patient with a sense of NAC continuity, where they won’t spend a portion of their lives without NACs. The fourth goal is retention or recreation of protective and erotic sensation. Arguably, this is the most challenging factor to achieve.

More than 30 techniques of NAC reconstruction have been described, including tattoo, local flaps, and nipple and areolar grafts, as well as alloplastic techniques. The wide use of variable techniques highlights that there are limitations to each method.8 Local flap reconstruction often fails to recreate durable projection, color, and texture.9 Local flaps also tend to be performed in a delayed fashion after patients have received radiation therapy, which include a number of complications listed above. Results of adjunctive techniques such as tattoo often fade and lack true projection.10 Recreation of erotic sensation is generally also lost with these techniques.

Patients who were considered for the DDSNS technique all presented to the clinic with plans for bilateral skin-sparing mastectomy. Most commonly these patients had significant ptosis, active smoking, prior radiation, or NAC-adjacent tumor factors that disqualified them as NSM candidates. Of all selected patients, none sustained a negative impact from an oncologic standpoint. All reported satisfaction with their NAC reconstruction. All reached adjuvant therapy in a timely manner, if indicated, and there were no required revisions or significant wound complications. Erotic sensation was not preserved: a similar outcome to alternate methods of NAC reconstruction.

Limitations

A cornerstone endpoint of breast reconstruction is patient satisfaction with their results. Anecdotally, all the included patients voiced satisfaction, but this has not yet been quantified in a validated survey for breast reconstruction. This is certainly an area requiring further evaluation in subsequent studies. The population of 31 patients with 62 breasts is underpowered for direct comparison with other techniques regarding risks. This cohort does not yet have follow-up beyond 9 months, and thus data is so far lacking on the durability of preserved pigmentation and projection. Similarly, late complications cannot yet be accounted for; however, prior studies of NAC grafting in breast reduction procedures suggest that pigmentation typically recovers with time. This study only looked at patients who underwent expander-to-implant subpectoral reconstruction. This technique has not yet been evaluated in pre-pectoral implant reconstructions, and it should be evaluated separately. Similarly, as direct-to-implant (DTI) reconstruction is becoming more commonplace, it would be prudent to evaluate this technique of nipple reconstruction in those patients.

Conclusions

Immediate nipple and areolar reconstruction in skin-sparing mastectomy patients with a DDSNS is proven to be an oncologically sound and an operatively simple option for NAC reconstruction. This technique can be safely used to provide an aesthetically pleasing result in patients who would otherwise not have nipples in the immediate phase. This technique negates the need for second-stage nipple reconstruction, which may otherwise be needed after a patient has received radiation and adjuvant chemotherapy. This technique should be strongly considered in patients presenting with any barrier to NSM, such as ptosis, prior radiation, or smoking, in addition to patients who have unilateral disease.

Acknowledgments

Affiliations: 1Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky; 2School of Medicine, University of Louisville of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky; 3Division of General Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky

Correspondence: Evan Westrick, MD; Evan.westrick@louisville.edu.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant conflict of interest or financial disclosures for this manuscript.

References

1. Adams W. Free transplantation of the nipples and areolae. Surgery. 1944;15(1):186-195. doi: https://doi.org/10.5555/uri:pii:S0039606044900589

2. Millard DR Jr. Nipple and areola reconstruction by split-skin graft from the normal side. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;50(4):350-353. doi:10.1097/00006534-197210000-00006

3. Clemens MW, Kronowitz SJ. Current perspectives on radiation therapy in autologous and prosthetic breast reconstruction. Gland Surg. 2015;4(3):222-231. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2015.04.03

4. Howard MA, Sisco M, Yao K, et al. Patient satisfaction with nipple-sparing mastectomy: A prospective study of patient reported outcomes using the BREAST-Q. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114(4):416-422. doi:10.1002/jso.24364

5. Sisco M, Kyrillos AM, Lapin BR, Wang CE, Yao KA. Trends and variation in the use of nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer in the United States. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;160(1):111-120. doi:10.1007/s10549-016-3975-9

6. Cho JW, Yoon ES, You HJ, Kim HS, Lee BI, Park SH. Nipple-areola complex necrosis after nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate autologous breast reconstruction. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42(5):601-607. doi:10.5999/aps.2015.42.5.601

7. Jadeja P, Ha R, Rohde C, et al. Expanding the criteria for nipple-sparing mastectomy in patients with poor prognostic features. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18(3):229-233. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2017.08.010

8. Nimboriboonporn A, Chuthapisith S. Nipple-areola complex reconstruction. Gland Surg. 2014;3(1):35-42. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2014.02.06

9. Kim JH, Ahn HC. A revision restoring projection after nipple reconstruction by burying four triangular dermal flaps. Arch Plast Surg. 2016;43(4):339-343. doi:10.5999/aps.2016.43.4.339

10. Levites HA, Fourman MS, Phillips BT, et al. Modeling fade patterns of nipple areola complex tattoos following breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;73 Suppl 2:S153-S156. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000000120