Unusual Clinical Presentation of a Benign Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor of the Radial Nerve

© 2023 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Diagnosis of simple benign peripheral nerve tumors (PNT) is usually based on imaging studies and in most cases, surgical excision leads to no significant functional deficit. The clinical presentation is often asymptomatic with incidental imaging findings. We present an unusual clinical presentation of a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the radial nerve.

Introduction

Diagnosis of simple benign peripheral nerve tumors (PNT) is usually based on imaging studies, and in most cases, surgical excision leads to no significant functional deficit.1,2 Nerve sheath tumors may be asymptomatic and present as incidental findings on imaging studies. When peripheral nerve sheath tumors are located in a superficially placed nerve, cause expansion of nerves in anatomically narrow locations, or become large enough to distort adjacent intact fascicles, they may be painful, elicit a Tinel’s sign when tapped, or cause sensory and motor disturbance depending on the nerve type. Autonomic disturbance is not usually a feature. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a benign PNT typically shows a well-circumscribed mass with low signal intensity on T1 weighting, with high signal intensity on T2 and T1 enhancement with contrast. There is no invasion of surrounding tissues, although large tumors may displace normal structures. Malignant PNTs are rare, and the clinical features include a rapid increase in size and neuropathic pain with sensory and/or motor deficits. MRI demonstrates heterogeneity, no clear boundaries, with infiltration and edema in surrounding tissues.3 We present a case in which the clinical, radiological, and intraoperative findings suggest a malignant tumor; however, the histological findings were consistent with a low-grade nonmalignant tumor.

Case Presentation

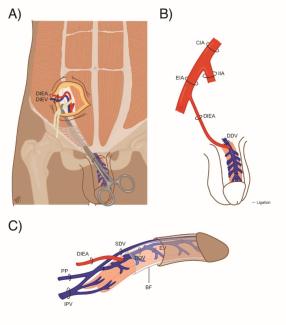

A 38-year-old female patient was assessed after a sudden onset of high radial nerve palsy without a history of preceding trauma. During the preceding 6 months, there was sensory disturbance and pain in the superficial radial nerve territory. Electrodiagnostic testing showed polyphasia in the brachioradialis and triceps and no other abnormalities. Imaging before referral with ultrasound and MRI showed a neuroma in the radial nerve in the vicinity of the lateral intermuscular septum (LIS) of the upper arm (Figure 1). Sudden deterioration in motor function and complete loss of sensory function in the radial nerve was accompanied by resolution of the neuropathic pain.

Following local review of the MRI, differential diagnosis included isolated inflammatory mononeuropathy, a granulomatous lesion of the radial nerve, perineurioma, or a malignant nerve sheath tumor. Repeat MRI neurography with diffuse tensor imaging was consistent with an atypical perineurioma with signal disruption and a complete lesion of the radial nerve at the level of the LIS with surrounding muscle edema.

On exploration, the radial nerve was in near-complete discontinuity, enlarged and with adhesions to muscle, and there was no distal function remaining at 6mA stimulation (Figure 2). A biopsy showed a low-grade tumor without evidence of malignancy, infection, granulomatous inflammation, or mycobacterial infection. A further procedure was completed when the histopathology was available. The radial nerve tumor was resected en bloc, and the resultant 40-mm gap was reconstructed with reversed sural nerve cable grafting from the leg. Concomitant triple tendon transfers were performed: pronator teres to extensor carpi radialis brevis, flexor carpi radialis to extensor digitorum communis, and palmaris longus to extensor pollicis longus for rapid functional restoration. The final histopathology report described a low-grade tumor without malignant features.

Discussion

This is, in our experience, a unique case because the clinical, radiological, and intraoperative findings were suggestive of a malignant PNT. After critically reviewing the case, we hypothesize that a perineurioma gradually grew at the LIS and partially ruptured due to ischemic compression. Compression of the radial nerve in the LIS itself has been noted to be rare; more commonly, compression occurs in the proximal fibrous canal instead. Despite this, the literature shows 2 cases of entrapment at this level that were associated with posttraumatic humeral mid-shaft fractures presenting 3 months and 10 years following the original injury, with no further cases identified by a literature review from these authors.4,5 Clinically, these cases presented as high radial nerve palsy, with varying symptoms, all solely caused by LIS compression. These presentations can include weakness of active extension in the wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints, ultimately progressing to wrist drop with weakness of thumb abduction. Sensation will often be reduced across the dorsoradial aspect of the hand, particularly the first dorsal web space. Pain, especially when illicited by Tinel’s sign test, is more indicative of nerve compression. A full upper limb examination must be performed to assess these patients to fully describe and evaluate the underlying pathology—for example, to rule out posterior cord lesions.6

To our knowledge, there is no similar case of spontaneous rupture related to nerve tumor at the LIS reported, emphasizing the importance of thorough examination and investigation. The clinical examination forms the basis of PNT assessment and, when combined with questioning to establish duration of symptoms and additional historical features (including family and medical history), and subsequent imaging, the risk of malignancy can be determined. MRI is the gold standard, and features like irregular margins and heterogeneous gadolinium enhancement raise suspicion.7 Preoperative histopathological and immunohistochemical samples may be taken to further influence treatment, although final microscopic examination is necessary in all cases. If proven malignant, a multidisciplinary approach should be taken that includes surgical intervention with wide excision margins, radiotherapy, and, in extreme cases, amputation.1 Despite these aggressive measures, treatment remains challenging with poor prognosis reported.7

Benign tumor management is more straightforward, with simple resection, individualized to tumor type, forming the mainstay of treatment.7 A conservative approach can be considered in the absence of symptoms, thus reducing associated surgical risk.1 Restoration of movement after loss of the radial nerve motor function may be achieved through nerve grafting, nerve transfers, or tendon transfers. The outcome for a nerve transfer in the setting of chronic compression, rupture, and intraneural scar is uncertain. Grafting for pain and function may be augmented with distal tendon transfers for key functions. Performing an end-to-side tendon transfer has the advantage of early restoration of wrist movement with the potential for further strengthening of the original muscle and enhanced recovery.

Perineuriomas are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors of perineural cells and much rarer than schwannomas and neurofibromas. Classically, they present as single lesions with slow progression with sensory and/or motor deficits. Histopathology is generally intrafascicular tumor cells surrounded by collagen fibers. The perineurioma evidenced here is an example of an intraneural perineural tumor, whereby the perineural proliferation infiltrates the endoneurium. As mentioned before, the intraneural type do not undergo malignant transformation. Other subtypes, which include extraneural and malignant, can be differentiated from schwannomas and neurofibromas by the staining of endothelial membrane antigen but not S100 protein.8 Perineural tumors also encompass the benign nerve sheath ganglions, from perineural injury, and neural fibrolipomas, from adipose and fibrous infiltration.1

Perineural tumors are also discussed when considering metastatic spread, as perineural invasion and subsequent tumors are a pathological feature of many malignancies and often associated with a poorer outcome. Furthermore some benign neoplasms, such as prostate cancer, also exhibit this tumor spread.9

Given the metastatic involvement and many subtypes of perineural tumors, further clinical education and research is necessary to optimize treatment and awareness. A recent systematic review of modern treatment of perineuriomas shows that there is still no consensus on surgical treatment.10 A patient-specific approach is advised, and surgery is recommended when there are progressive neurological deficits resulting from nerve grafting, nerve transfers, and tendon transfers; all options should be considered for pain management and functional reconstruction.

Acknowledgments

Affiliations: 1Peripheral Nerve Surgery Department, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom; 2Plastic, Reconstructive and Hand Surgery Department, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; 3University of Leicester, Leicester Medical School, Leicester, United Kingdom; 4Department of Burns and Plastic Surgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom; 5Institute of Inflammation and Ageing, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

Correspondence: Dominic M Power, FRCS; Dominic.Power@uhb.nhs.uk

Ethics: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Disclosures: Hadyn KN Kankam is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Academic Clinical Fellow. No direct funding was received for this review. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

1. Zhou HY, Jiang S, Ma FX, Lu H. Peripheral nerve tumors of the hand: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Clin Cases. 2020 Nov 6;8(21):5086-5098. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5086

2. Belakhoua SM, Rodriguez FJ. Diagnostic pathology of tumors of peripheral nerve. Neurosurgery. 2021 Feb 16;88(3):443-456. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyab021

3. Holzgrefe RE, Wagner ER, Singer AD, Daly CA. Imaging of the peripheral nerve: concepts and future direction of magnetic resonance neurography and ultrasound. J Hand Surg Am. 2019 Dec;44(12):1066-1079. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2019.06.021

4. Bowman J, Curnutte B, Andrews K, Stirton J, Ebraheim N, Mustapha AA. Lateral intermuscular septum as cause of radial nerve compression: case report and review of the literature. J Surg Case Rep. 2018 Aug;2018(8):rjy226. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjy226

5. Chesser TJ, Leslie IJ. Radial nerve entrapment by the lateral intermuscular septum after trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2000 Jan;14(1):65-66. doi:10.1097/00005131-200001000-00013

6. Laulan J. High radial nerve palsy. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2019 Feb;38(1):2-13. doi:10.1016/j.hansur.2018.10.243

7. Guha D, Davidson B, Nadi M, et al. Management of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: 17 years of experience at Toronto Western Hospital. J Neurosurg. 2018 Apr 1;128(4):1226-1234. doi:10.3171/2017.1.JNS162292

8. Brand C, Pedro MT, Pala A, et al. Perineurioma: a rare entity of peripheral nerve sheath tumors. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2022 Jan;83(01):001-005. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1726110

9. Liebig C, Ayala G, Wilks JA, Berger DH, Albo D. Perineural invasion in cancer: a review of the literature. Cancer. 2009;115(15):3379-3391. doi:10.1002/cncr.24396

10. Uerschels AK, Krogias C, Junker A, Sure U, Wrede KH, Gembruch O. Modern treatment of perineuriomas: a case-series and systematic review. BMC Neurology. 2020 Feb 13;20(1):55. doi:10.1186/s12883-020-01637-z